LESSON 3 General Aviation Takes Flight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gulfstream GV / GV-SP (G500/G550) / GIV-X (G450/G350)

Gulfstream EASA-OSD-FC-GV Series-GAC-001, Basic Issue Document Reference # Operational Suitability Data (OSD) Flight Crew Gulfstream GV / GV-SP (G500/G550) / GIV-X (G450/G350) 21 May 2015 Operational Suitability Data – Flight Crew G-V Gulfstream GV / GV-SP (G500/G550) / GIV-X (G450/G350) Operational Suitability Data (OSD) – Flight Crew This OSD document is provided on behalf of Gulfstream Aerospace. It is made available to users in accordance with paragraph 21.A.62 of Part-21. Users should verify the currency of this document. Revision Record Rev. No. Content Date JOEB Report JOEB report Gulfstream GV / GV-SP (G500/G550) 15 Jun 2006 Rev. 7 / GIV-X (G450/G350) OSD FC Replaces and incorporates the JOEB report for the Gulfstream GV / GV-SP (G500/G550) / GIV-X 21 May 2015 Original (G450/G350) OSD FC G-V – Original 21 May 2015 Page 2 of 37 Operational Suitability Data – Flight Crew G-V Contents Revision Record ........................................................................................................................... 2 Contents ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Preamble ..................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................... -

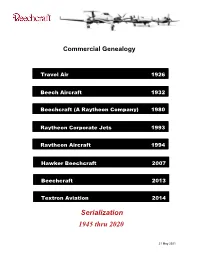

Serialization List Year Produced MODEL 18 D18S A-1 Thru A-37 1945 37

Commercial Genealogy Travel Air 1926 Beech Aircraft 1932 Beechcraft (A Raytheon Company) 1980 Raytheon Corporate Jets 1993 Raytheon Aircraft 1994 Hawker Beechcraft 2007 Beechcraft 2013 Textron Aviation 2014 Serialization 1945 thru 2020 21 May 2021 HAWKER 4000 BRITISH AEROSPACE AIRCRAFT HAWKER 1000 HAWKER 900XP HAWKER SIDDELEY 125-400 BEECHCRAFT HAWKER 125-400 U125A HAWKER 800 • HAWKER SIDDELEY 125 HAWKER 800XP HAWKER 800XPi HAWKER 850 HAWKER 800XPR SERIES 1 HAWKER 125-700 HAWKER 750 HAWKER 125-600 MODEL 400 BEECHJET • HAWKER SIDDELEY 125 400A BEECHJET 400A HAWKER 400XP HAWKER 400XPR SERIES 3 S18A T1A XA-38 GRIZZLY MODEL 2000 STARSHIP PREMIER I PREMIER IA S18 AT-10 KING AIR 350ER F2 KING AIR 350 • • • UC-45 U-21J SUPER KING AIR 300 KING AIR 350i KING AIR 350i D18S C45H SUPER E18 • • KING AIR B200 MODEL 18 SUPER H18 • • TWIN BEECH SUPER KING AIR 200 KING AIR B200GT KING AIR 250 KING AIR 250 C-12 AIR FORCE C-12 NAVY JRB-1 C-12 ARMY 1300 AIRLINER • • • • RC-12K C-12K JRB-2 • JRB-6 C-12 AIR FORCE U21F AT-11 • C-12 NAVY/MARINES KING AIR 100 • • • AT-7 KING AIR A100 B100 C-12 ARMY VC-6A B90 KING AIR B100 Legendary Innovation— • • • C90 SNB-1 MODEL 90 KING AIR T-44A E90 F90 KING AIR C90A Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. SNB-2 • SNB-5P • • KING AIR C90B KING AIR C90GT KING AIR C90GTx KING AIR C90GTx U-21 RU-21 KING AIR F90-1 With a rich history dating back more than 80 years, Beechcraft Corporation continues to design, build NU-8F MODEL 99 AIRLINER B99 • and support a versatile and globally renowned fl eet of aircraft. -

Runway Analysis

CHAPTER 5 RUNWAY ANALYSIS 5 5 RUNWAY ANALYSIS INTRODUCTION The primary issue to be addressed in the William R. Fairchild International Airport (CLM) Master Plan involves the ultimate length and configuration of the runway system. At present there are two runways; primary Runway 8/26 and crosswind Runway 13/31. Runway 8/26 is 6,347 feet long and 150-feet wide with a displaced threshold of 1,354 feet on the approach end to Runway 26. The threshold was displaced to provide for an unobstructed visual approach slope of 20:1. Runway 13/31 is designated as the crosswind runway and is 3,250-feet long by 50-feet wide. In the 1997 ALP Update, the FAA determined that this runway was not required to provide adequate wind coverage and would not be eligible for FAA funding of any improvements in the future. The Port of Port Angeles has committed to keeping this runway functional without FAA support for as long as it is feasible. Subsequent sections of this analysis will reexamine the need for the runway. Both runways are supported by parallel taxiway systems with Taxiway A serving Runway 8/26 and Taxiway J for Runway 13/31. Taxiway A is 40 feet wide and Taxiway J is 50 feet wide. AIRFIELD REQUIREMENTS In determining airfield requirements, FAA Advisory Circular (AC) 150/5300-13, Airport Design (Change 14), has been consulted. This circular requires that future classification of the airport be defined as the basis for airfield planning criteria. As shown in the forecast chapter, the critical aircraft at CLM is expected to be the small business jet represented by the Cessna Citation within 5-years. -

Version: July, 2020 WHICH MICHELIN® TIRE IS RIGHT for YOUR AIRCRAFT? General Aviation Airframer Model SERIES Positionsize Part

Version: July, 2020 WHICH MICHELIN® TIRE IS RIGHT FOR YOUR AIRCRAFT? General Aviation Airframer Model SERIES PositionSize Part NumbeSR Ply Techno ADAM AIRCRAFT A500 A500 NOSE 6.00-6 070-317-1 160 8 BIAS ADAM AIRCRAFT A700 A700 NOSE 6.00-6 070-317-1 160 8 BIAS AERMACCHI M290 L90 RediGO NOSE 5.00-5 070-312-0 120 6 BIAS AERMACCHI S211 A MAIN 6.50-8 025-338-0 160 8 BIAS AIR TRACTOR AT401 AT401 MAIN 8.50-10 025-349-0 160 8 BIAS AIR TRACTOR AT402 AT402 MAIN 8.50-10 025-349-0 160 8 BIAS AIR TRACTOR AT502 MAIN 29x11.0-10 076-446-1 160 10 BIAS AIR TRACTOR AT802 AT802 MAIN 11.00-12 021-355-0 160 10 BIAS ALON F1A AIRCOUPE MAIN 6.00-6 070-315-0 120 4 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 260 A BELLANCA MAIN 6.00-6 070-314-0 120 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 17-30 A VIKING MAIN 6.00-6 070-314-0 120 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 17-30 A VIKING NOSE 15X6.0-6 070-449-0 160 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 17-31 A SUPER VIKING MAIN 6.00-6 070-314-0 120 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 17-31 A SUPER VIKING NOSE 15X6.0-6 070-449-0 160 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 17-31 ATC TURBO VIKING MAIN 6.00-6 070-314-0 120 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 17-31 ATC TURBO VIKING NOSE 15X6.0-6 070-449-0 160 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 7CBC CITABRIA MAIN 7.00-6 070-313-0 120 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 7EC CHAMP MAIN 6.00-6 070-314-0 120 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 7ECA CITABRIA AURORA MAIN 6.00-6 070-314-0 120 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 7GCAA CITABRIA ADVENTURE MAIN 6.00-6 070-314-0 120 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 7KCAB CITABRIA MAIN 7.00-6 070-313-0 120 6 BIAS AMERICAN CHAMPION 8KCAB SUPER DECATHLON MAIN 6.00-6 070-314-0 120 6 BIAS -

Arctic Discovery Seasoned Pilot Shares Tips on Flying the Canadian North

A MAGAZINE FOR THE OWNER/PILOT OF KING AIR AIRCRAFT SEPTEMBER 2019 • VOLUME 13, NUMBER 9 • $6.50 Arctic Discovery Seasoned pilot shares tips on flying the Canadian North A MAGAZINE FOR THE OWNER/PILOT OF KING AIR AIRCRAFT King September 2019 VolumeAir 13 / Number 9 2 12 30 36 EDITOR Kim Blonigen EDITORIAL OFFICE 2779 Aero Park Dr., Contents Traverse City MI 49686 Phone: (316) 652-9495 2 30 E-mail: [email protected] PUBLISHERS Pilot Notes – Wichita’s Greatest Dave Moore Flying in the Gamble – Part Two Village Publications Canadian Arctic by Edward H. Phillips GRAPHIC DESIGN Rachel Wood by Robert S. Grant PRODUCTION MANAGER Mike Revard 36 PUBLICATIONS DIRECTOR Jason Smith 12 Value Added ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Bucket Lists, Part 1 – John Shoemaker King Air Magazine Be a Box Checker! 2779 Aero Park Drive by Matthew McDaniel Traverse City, MI 49686 37 Phone: 1-800-773-7798 Fax: (231) 946-9588 Technically ... E-mail: [email protected] ADVERTISING ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR AND REPRINT SALES 22 Betsy Beaudoin Aviation Issues – 40 Phone: 1-800-773-7798 E-mail: [email protected] New FAA Admin, Advertiser Index ADVERTISING ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT PLANE Act Support and Erika Shenk International Flight Plan Phone: 1-800-773-7798 E-mail: [email protected] Format Adopted SUBSCRIBER SERVICES by Kim Blonigen Rhonda Kelly, Mgr. Kelly Adamson Jessica Meek Jamie Wilson P.O. Box 1810 24 Traverse City, MI 49685 1-800-447-7367 Ask The Expert – ONLINE ADDRESS Flap Stories www.kingairmagazine.com by Tom Clements SUBSCRIPTIONS King Air is distributed at no charge to all registered owners of King Air aircraft. -

Aviation Activity Forecasts BOWERS FIELD AIRPORT AIRPORT MASTER PLAN

Chapter 3 – Aviation Activity Forecasts BOWERS FIELD AIRPORT AIRPORT MASTER PLAN Chapter 3 – Aviation Activity Forecasts The overall goal of aviation activity forecasting is to prepare forecasts that accurately reflect current conditions, relevant historic trends, and provide reasonable projections of future activity, which can be translated into specific airport facility needs anticipated during the next twenty years and beyond. Introduction This chapter provides updated forecasts of aviation activity for Kittitas County Airport – Bowers Field (ELN) for the twenty-year master plan horizon (2015-2035). The most recent FAA-approved aviation activity forecasts for Bowers Field were prepared in 2011 for the Airfield Needs Assessment project. Those forecasts evaluated changes in local conditions and activity that occurred since the previous master plan forecasts were prepared in 2000, and re-established base line conditions. The Needs Assessment forecasts provide the “accepted” airport-specific projections that are most relevant for comparison with the new master plan forecasts prepared for this chapter. The forecasts presented in this chapter are consistent with Bowers Field’s current and historic role as a community/regional general aviation airport. Bowers Field is the only airport in Kittitas County capable of accommodating a full range of general aviation activity, including business class turboprops and business jets. This level of capability expands the airport’s role to serve the entire county and the local Ellensburg community. The intent is to provide an updated set of aviation demand projections for Bowers Field that will permit airport management to make the decisions necessary to maintain a viable, efficient, and cost-effective facility that meets the area’s air transportation needs. -

Light Commercial and General Aviation Chair: Gerald S

A1J03: Committee on Light Commercial and General Aviation Chair: Gerald S. McDougall, Southeast Missouri State University Light Commercial and General Aviation Growth Opportunities Will Abound GERALD W. BERNSTEIN, Stanford Transportation Group DAVID S. LAWRENCE, Aviation Market Research The new millennium offers numerous opportunities for light commercial and general aviation. The extent to which this diverse industry can take advantage of these opportunities depends on our ability to: (1) maintain steady, albeit slow, economic growth; (2) undertake research and development of new and enhanced technologies that improve performance and lower costs, (3) forge alliances and approach aircraft production from a total system perspective; and (4) develop and maintain an air traffic system (facilities and control) that is able to efficiently accommodate the expected growth in demand for all categories of air travel. The greatest challenge for the industry is whether government policies and regulations continue to adhere to fiscal and monetary policies that promote economic growth worldwide and provide the necessary investments in our air traffic system to reduce congestion and avoid the distorting influences of user fees or artificial limits to access. HELICOPTER AVIATION Subcommittee A1J03 (1) The helicopter industry can be characterized as technologically mature but unstable in the structure of both its manufacturing and operating sectors. This anomaly is the result of worldwide reductions in military helicopter procurement after years of buildup as well as reduced tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. In addition, and not unrelated to military cutbacks, the trend toward consolidation of military contractors has seriously affected the mostly subsidiary helicopter business. -

“Sam” Uhl Aviation Photograph Collection .7 Linear Feet Accession

Guide to the A. J. “Sam” Uhl Aviation Photograph Collection .7 Linear Feet Accession Number: 78-04 Collection Number: H78-04 Prepared By Paul A. Oelkrug, C.A. Malcolm Swain 18 October 2005 CITATION: The A. J. “Sam” Uhl Aviation Photograph Collection, Box Number, Folder Number, Special Collections Department, McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas. Special Collections Department McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas Table of Contents Biographical Sketch............................................................................................................ 1 Sources:........................................................................................................................... 1 Related Sources in The History of Aviation Collection: ................................................ 1 Series Description ............................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Content .............................................................................................................. 2 Provenance Statement......................................................................................................... 2 Note to the Researcher........................................................................................................ 2 Literary Rights Statement ................................................................................................... 2 H78-04 The A. J. “Sam” Uhl Aviation Photograph Collection: Container List.............. -

June 2021 Issue 45 Ai Rpi Lo T

JUNE 2021 ISSUE 45 AI RPI LO T INSIDE HRHTHE DUKE OF EDINBURGH 1921-2021 A Portrait of our Patron RED ARROWS IN 2021 & BEYOND Exclusive Interview with Red One OXFORD v CAMBRIDGE AIR RACE DIARY With the gradual relaxing of lockdown restrictions the Company is hopeful that the followingevents will be able to take place ‘in person’ as opposed to ‘virtually’. These are obviously subject to any subsequent change THE HONOURABLE COMPANY in regulations and members are advised to check OF AIR PILOTS before making travel plans. incorporating Air Navigators JUNE 2021 FORMER PATRON: 26 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Duxford His Royal Highness 30 th T&A Committee Air Pilot House (APH) The Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh KG KT JULY 2021 7th ACEC APH GRAND MASTER: 11 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Henstridge His Royal Highness th The Prince Andrew 13 APBF APH th Duke of York KG GCVO 13 Summer Supper Girdlers’ Hall 15 th GP&F APH th MASTER: 15 Court Cutlers’ Hall Sqn Ldr Nick Goodwyn MA Dip Psych CFS RAF (ret) 21 st APT/AST APH 22 nd Livery Dinner Carpenters’ Hall CLERK: 25 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Weybourne Paul J Tacon BA FCIS AUGUST 2021 Incorporated by Royal Charter. 3rd Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Lee on the Solent A Livery Company of the City of London. 10 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Popham PUBLISHED BY: 15 th Air Pilot Flying Club The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, Summer BBQ White Waltham Air Pilots House, 52A Borough High Street, London SE1 1XN SEPTEMBER 2021 EMAIL : [email protected] 15 th APPL APH www.airpilots.org 15 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Oaksey Park th EDITOR: 16 GP&F APH Allan Winn EMAIL: [email protected] 16 th Court Cutlers’ Hall 21 st Luncheon Club RAF Club DEPUTY EDITOR: 21 st Tymms Lecture RAF Club Stephen Bridgewater EMAIL: [email protected] 30 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Compton Abbas SUB EDITOR: Charlotte Bailey Applications forVisits and Events EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTIONS: The copy deadline for the August 2021 edition of Air Pilot Please kindly note that we are ceasing publication of is 1 st July 2021. -

FALL 2003 - Volume 50, Number 3 Put High-Res Scan Off ZIP Disk of Book Cover in This Blue Space Finished Size: 36 Picas Wide by 52 Picas High

FALL 2003 - Volume 50, Number 3 Put high-res scan off ZIP disk of book cover in this blue space finished size: 36 picas wide by 52 picas high Air Force Historical Foundation Benefits of Membership Besides publishing the quarterly journal Air Power History, the Foundation fulfills a most unique mis- sion by acting as a focal point on matters relating to air power generally, and the United States Air Force in particular. Among its many worthy involvements, the Foundation underwrites the publication of meaningful works in air power history, co-sponsors air power symposia with a national scope, and provides awards to deserving scholars. In 1953, a virtual “hall of fame” in aviation, including Generals Spaatz, Eaker Vandenberg, Twining, andFoulois, met to form the Air Force Historical Foundation, “to preserve and perpetuate the history and traditions of the U.S. Air Force and its predecessor organizations and of those whose lives have been devoted to the service.” By joining, one becomes part of this great fellowship doing worth- Exclusive Offer for Air Force Historical Foundation Members while work, and receives an exceptional quarterly publication as well. See page 55 for details. Come Join Us! Become a member. FALL 2003 - Volume 50, Number 3 Why the U.S. Air Force Did Not Use the F–47 Thunderbolt in the Korean War Michael D. Rowland 4 “Big Ben”: Sergeant Benjamin F. Warmer III, Flying Ace John W. Hinds 14 The Dark Ages of Strategic Airlift: the Propeller Era Kenneth P. Werrell 20 Towards a Place in History David G. Styles 34 Remembrance Richard C. -

Final Report Cessna -152 Aircraft Accident Investigation in Bangladesh

FINAL REPORT CESSNA -152 AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION IN BANGLADESH FINAL REPORT Aircraft Cessna-152; Training Flight Call Sign S2-ADI Shah Makhdum Airport, Rajshahi, Bangladesh Cessna-152 Aircraft of Flying Academy & General Aviation Ltd. This is to certify that this report has been compiled as per the provisions of ICAO Annex 13 for all concerned. The report has been authenticated and is hereby Approved by the undersigned with a view to ensuring prevention of aircraft accident and that the purpose of this activity is not to apportion blame or liability. Capt Salahuddin M Rahmatullah Head of Aircraft Accident Investigation Group of Bangladesh CAA Headquarters, Kurmitola, Dhaka, Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected] _____________________________________________________________________________________ AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION GROUP OF BANGLADESH (AAIG-BD) 28 MAY 2017 PAGE | 0 FINAL REPORT CESSNA -152 AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION IN BANGLADESH TABLE OF CONTENTS SL NO TITLE Page No 0 Synopsis 2 1 BODY (FACTUAL INFORMATION) 2 1.1 Introductory Information 2 1.2 Impact Information 3 Protection and Recovery of Wreckage and Disposal of 1.3 4 Diseased/Injured Persons 1.4 Analytical information 4 2 ANALYSIS 7 2.1 General 7 2.2 Flight Operations and others 7 2.3 Cause Analysis 10 3 CONCLUSION 12 3.1 Findings 12 3.1.2 Crew/Pilot 13 3.1.3 Operations 13 3.1.4 Operator 14 3.1.5 Air Traffic Services and Airport Facilities 14 3.1.6 Medical 14 3.2 CAUSES 14 3.2.1 Primary Causes 14 3.2.2 Primary Contributory Causes 15 4 SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS 15 _____________________________________________________________________________________ AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION GROUP OF BANGLADESH (AAIG-BD) 28 MAY 2017 PAGE | 1 FINAL REPORT CESSNA -152 AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION IN BANGLADESH 0. -

General Aviation Activity and Airport Facilities

New Hampshire State Airport System Plan Update CHAPTER 2 - AIRPORT SYSTEM INVENTORY 2.1 INTRODUCTION This chapter describes the existing airport system in New Hampshire as of the end of 2001 and early 2002 and served as the database for the overall System Plan. As such, it was updated throughout the course of the study. This Chapter focuses on the aviation infrastructure that makes up the system of airports in the State, as well as aviation activity, airport facilities, airport financing, airspace and air traffic services, as well as airport access. Chapter 3 discusses the general economic conditions within the regions and municipalities that are served by the airport system. The primary purpose of this data collection and analysis was to provide a comprehensive overview of the aviation system and its key elements. These elements also served as the basis for the subsequent recommendations presented for the airport system. The specific topics covered in this Chapter include: S Data Collection Process S Airport Descriptions S Airport Financing S Airport System Structure S Airspace and Navigational Aids S Capital Improvement Program S Definitions S Scheduled Air Service Summary S Environmental Factors 2.2 DATA COLLECTION PROCESS The data collection was accomplished through a multi-step process that included cataloging existing relevant literature and data, and conducting individual airport surveys and site visits. Division of Aeronautics provided information from their files that included existing airport master plans, FAA Form 5010 Airport Master Records, financial information, and other pertinent data. Two important element of the data collection process included visits to each of the system airports, as well as surveys of airport managers and users.