UTAH MINING 2017 by Taylor Boden, Ken Krahulec, Michael Vanden Berg, and Andrew Rupke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kennecott Utah Copper-Sustainable Over Time PHOTOS/VIDEO AUDIO

1 UNIVERSITY OF UTAH DEPARTMENT OF MINING ENGINEERING PRESENTATION to IMOA by Louie Cononelos “Kennecott Utah Copper-Sustainable Over Time PHOTOS/VIDEO AUDIO This is a story that had its beginning over 150 ago…and that story is still being written today. It began in Bingham Canyon, Utah located about 26 miles southwest of Salt Lake City, which was destined to become one of the greatest “mining camps” anywhere in the country. Mining in Utah, which was part of Spanish Mexico, can be traced back to Spanish miners in the mid-1700s. The start of mining in Utah, however, is credited to the United States Army in 1863. Troops under the command of Colonel Patrick Connor are credited with the discovery of Utah’s first mining claim and helping to form the first mining company and mining district in Bingham Canyon. The early mining at Bingham was underground with the exception of placer mining. 2 Bingham Canyon was a beehive of mining activity at the turn of the Century. Dozens of small companies dug tunnels and sank shafts in the mountains where they were mining lead, silver and gold ores…but not the low- grade copper ores that were in abundance and considered a nuisance. Then, along came Daniel C. Jackling, a 29-year-old metallurgical engineer, who with his partner, a mining engineer named Robert Gemmell, studied and assayed ore samples from the operations that dotted the canyon. They determined that there were vast tonnages of low- grade copper ore in the main mountain that divided the canyon…it was the kind of ore the mining companies tried to avoid because it interfered with the recovery of the metals they were mining. -

Lined Piping List.Xlsx

3516 East 13th Ave Hibbing, MN 55746 Suite 700, 407-2nd St SW Calgary, AB T2P 2Y3 www.iracore.com 218-262-5211 Partial Listing of Rubber Lined Piping Systems Installed Customers Pipe Diameter Inches Product Transport Lengths Linear Feet LTV Steel 14” Taconite/Tailings 40’ 155,160 Cleveland Cliffs 24” and 26” Taconite/Tailings 20’ to 40’ 58,310 Iron Ore Co. of Canada 20’ Taconite/Tailings 38’ 56,824 Eveleth Mine 16” and 18” Taconite/Tailings 40’ 35,000 National Steel 22” Taconite/Tailings 40’ 51,040 Homestake Gold Mine 4”, 5”, 6” Gold 10’, 20’, 40’ 45,000 MN Power and Light 12” and 18” Power Generation Various 12,000 Wabush Mines Canada 3” to 18” Taconite/Tailings Various 5,000 Unimin 10” Aggragate 40’ 10,000 US Steel 4” to 12” Taconite/Tailings Various 75,000 Cheme (for MN Power) 6” to 30” Power Generation Various 20’ 25,000 SMARCO 20” Iron Ore Various 10,000 Butler Tac 14” Taconite/Tailings Various 100,000 Misc. Power Plants 3” to 30” Power Generation Various 200,000 Chino Mines 12” to 22” Copper/Tailings Various 10,000 Azco 3” to 30” Gold / Copper Various 25,000 Allegheny Power 4” to 36” Power Generation Various 25,000 Harrison Station, WV Kennecott Utah Copper 12”, 28”, 38”, 54”, 60”, 66” Copper/Tailings 60’ 175,000 BHP Nevada Mining 30” Gold / Copper 50’, 60’ 7,850 NY State Electric & Gas 6” and 8” Power Generation Various 1,000 Corporation BATU HIJAU 3” to 44” Gold/Tailings 1” to 60’ 23,970 Newmont Gold ROYAL OAK MINES 24” to 36” Copper/Tailings 40’, 60’ 60,000 Kemess Site Duro Felguera 3" to 30" Iron Ore Various 20,000 Venezuela FMI Bagdad 34" Copper 40’ 8,000 Arizona Hibbing Taconite 16" and 18" Taconite/Tailings 40' , 50' 35,000 Minnesota Suncor 8" Gypsum Slurry 20' , 40’ 12,000 Alberta, Canada Note: The above listed major jobs also included fittings, elbows, etc., which are not included in total linear feet lined. -

Kennecott and Utah's Air Quality

Utah October 2018 kennecott.com/air-quality Kennecott and Utah’s air quality A closer look at winter inversion Wasatch Front Utah continues to have wintertime air quality problems During the winter, Kennecott shuts down its power despite decades of air quality regulations on companies plant reducing the amount of fine particulate emissions like Rio Tinto’s Kennecott Utah Copper. Utah meets the to 3.8 percent of a typical winter day. Additionally, EPA’s annual standard for fine particulate emissions (PM2.5) Kennecott has been actively working to decrease throughout the year. However, the state struggles to meet emissions from the other sources that contribute to the 24-hour standard during the winter inversion season, inversions, such as transportation and area sources. on average about 20-days per year. Though it will take the entire community working According to the Utah Division of Air Quality, Kennecott together to be successful, Kennecott is committed is responsible for 4.4 percent of the annual fine particulate to doing its part. emissions in the Salt Lake air shed. Kennecott’s impact on the valley’s air, especially during an inversion is To learn more, take a closer look at even less. kennecott.com/air-quality. From ore to more: our work makes modern life possible. Cu October 2018 kennecott.com/air-quality Kennecott Utah Copper Kennecott’s contribution to Utah’s air quality 6390 ft. 6390 aboveft. sea6390 level ft. above sea level above sea level Bingham Canyon Mine 6390Bingham ft. CanyonBingham Mine Canyon Mine 5550above sea f levelt. elevation 5550elevation aboveft. -

Kennecott Utah Copper Corporation

Miningmining BestPractices Plant-Wide Assessment Case Study Industrial Technologies Program Kennecott Utah Copper Corporation: Facility Utilizes Energy Assessments to Identify $930,000 in Potential Annual Savings BENEFITS • Identified potential annual cost savings of $930,000 Summary • Identified potential annual savings of Kennecott Utah Copper Corporation (KUCC) used targeted energy assessments in the smelter 452,000 MMBtu in natural gas and refinery at its Bingham Canyon Mine, near Salt Lake City, Utah, to identify projects to • Found opportunities to reduce maintenance, conserve energy and improve production processes. By implementing the projects identified repair costs, waste, and environmental during the assessment, KUCC could realize annual cost savings of $930,000 and annual energy emissions savings of 452,000 million British thermal units (MMBtu). The copper smelting and refining • Found opportunities to improve industrial facilities were selected for the energy assessments because of their energy-intensive processes. Implementing the projects identified in the assessments would also reduce maintenance, hygiene and safety repair costs, waste, and environmental emissions. One project would use methane gas from • Identified ways to improve process an adjacent municipal dump to replace natural gas used to heat the refinery electrolyte. throughput Public-Private Partnership • Identified a potential payback period of less than 1 year for all projects combined The U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Industrial Technologies Program (ITP) cosponsored the assessment. DOE promotes plant-wide energy-efficiency assessments that will lead to improvements in industrial energy efficiency, productivity, and global competitiveness, while reducing waste and environmental emissions. In this case, DOE contributed $100,000 of the total $225,000 assessment cost. -

Governs the Making of Photocopies Or Other Reproductions of Copyrighted Materials

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. (Photo: Kennecott) Bingham Canyon Landslide: Analysis and Mitigation GE 487: Geological Engineering Design Spring 2015 Jake Ward 1 Honors Undergraduate Thesis Signatures: 2 Abstract On April 10, 2013, a major landslide happened at Bingham Canyon Mine near Salt Lake City, Utah. The Manefay Slide has been called the largest non-volcanic landslide in modern North American history, as it is estimated it displaced more than 145 million tons of material. No injuries or loss of life were recorded during the incident; however, the loss of valuable operating time has a number of slope stability experts wondering how to prevent future large-scale slope failure in open pit mines. This comprehensive study concerns the analysis of the landslide at Bingham Canyon Mine and the mitigation of future, large- scale slope failures. The Manefay Slide was modeled into a two- dimensional, limit equilibrium analysis program to find the controlling factors behind the slope failure. It was determined the Manefay Slide was a result of movement along a saturated, bedding plane with centralized argillic alteration. -

Reuse and the Benefit to Community: Kennecott South Zone Superfund Site

Reuse and the Benefit to Community Kennecott South Zone Introduction Mining has long been a way of life in and around Utah’s Bingham Canyon. Few ore deposits in the world have been more productive than those found at Bingham Canyon Mine. The mine has produced millions of tons of copper and tons of gold and silver. Mining operations also contaminated soil, surface water and groundwater in the surrounding area, referred to by regulators as the Kennecott South Zone (the site). During cleanup discussions, the site’s potentially responsible party, Kennecott Utah Copper, LLC (Kennecott), proposed a course of action that would address contamination while avoiding placing the site on the Superfund program’s National Priorities List (NPL). This approach was the template for the Superfund Alternative Approach, which has since been used at sites across the country. EPA approved the cleanup plan, setting the stage for the site’s cleanup and remarkable redevelopment. Open communication, extensive collaboration and innovative thinking helped contribute to the transformation of this once contaminated, industrial site into a thriving residential area and regional economic hub. Superfund site restoration and reuse can revitalize local economies with jobs, new businesses, tax revenues and local spending. Cleanup may also take place while active land uses remain on site. This case study focuses on the Kennecott South Zone, primarily on operable unit (OU) 7 and an area known as the Daybreak development, which includes and surrounds OU7. Today, OU7 and several other parts of the site support a wide range of commercial, industrial, public service, residential and recreational reuses. -

Failure to Capture and Treat Wastewater

U.S. OPERATING COPPER MINES: FAILURE TO CAPTURE & TREAT WASTEWATER BY BONNIE GESTRING, MAY 2019 In 2012, Earthworks released a report documenting the failure to capture and treat mine wastewater at U.S. operating copper mines accounting for 89% of U.S. copper production.1 The report found that 92% failed to capture and control mine wastewater, resulting in significant water quality impacts. This is an update to that effort. We reviewed government and industry documents for fifteen operating open-pit copper mines, representing 99% of U.S. copper production in 2015 – the most recent data on copper production available from the U.S. Geological Survey (see Table 1). Our research found similar results: 14 out of 15 (93%) failed to capture and control wastewater, resulting in significant water quality impacts (see TaBle 2). These unauthorized wastewater releases occurred from a number of different sources including uncontrolled seepage from tailings impoundments, waste rock piles, open pits, or other mine facilities, or failure of water treatment facilities, pipeline failures or other accidental releases. TABLE 1: Copper production from top 15 (as of 2015) U.S. open-pit copper mines (most recent data availaBle from USGS).2 MINE PRODUCTION (metric tons) Morenci 481,000 Chino 142,000 Safford 91,600 Bagdad 95,300 Bingham Canyon 92,000 Sierrita 85,700 Ray 75,100 Pinto Valley 60,400 Mission CompleX 68,300 Robinson 56,800 Tyrone 38,100 Continental pit 31,000 PhoeniX 21,100 Miami 19,500 Silver Bell 19,300 Total (99% of U.S. production) 1,377,000 U.S. -

Hardrock Mining in Utah

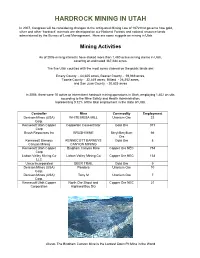

HARDROCK MINING IN UTAH In 2007, Congress will be considering changes to the antiquated Mining Law of 1872 that governs how gold, silver and other ‘hardrock’ minerals are developed on our National Forests and national resource lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management. Here are some nuggets on mining in Utah. Mining Activities As of 2006 mining interests have staked more than 1,480 active mining claims in Utah, covering an estimated 367,244 acres. The five Utah counties with the most acres claimed on the public lands are: Emery County - 64,605 acres, Beaver County - 59,969 acres, Tooele County - 32,449 acres, Millard - 26,252 acres, and San Juan County - 20,825 acres In 2006, there were 10 active or intermittent hardrock mining operations in Utah, employing 1,402 on site, according to the Mine Safety and Health Administration, representing 0.12% of the total employment in the state of Utah. Controller Mine Commodity Employment Denison Mines (USA) WHITE MESA MILL Uranium Ore 22 Corp. Kennecott Utah Copper Copperton Concentrator Gold Ore 371 Corp Brush Resources Inc BRUSH MINE Beryl-Beryllium 66 Ore Kennecott Barneys KENNECOTT BARNEYS Gold Ore 8 Canyon Mining CANYON MINING Kennecott Utah Copper Bingham Canyon Mine Copper Ore NEC 754 Corp Lisbon Valley Mining Co Lisbon Valley Mining Co Copper Ore NEC 134 LLC Unico Incorporated DEER TRAIL Gold Ore 9 Denison Mines (USA) Pandora Uranium Ore 10 Corp. Denison Mines (USA) Tony M Uranium Ore 7 Corp. Kennecott Utah Copper North Ore Shoot and Copper Ore NEC 21 Corporation Highland Boy DG Above: The Bingham Canyon Mine is the Largest Open Pit Mine in the World Area of Specific Concern – Jacobs Smelter Historically, the Rush Lake/Stockton area was a smelting center that processed ore from several of the mines in the area. -

Kennecott Utah Copper Retrofits Smelting

BestPractices MINING Technical Case Study OFFICE OF INDUSTRIAL TECHNOLOGIES August 2001 ENERGY EFFICIENCY AND RENEWABLE ENERGY, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY BENEFITS Kennecott Utah Copper Retrofits Smelting Applications • 55 percent energy savings in from Air-Fuel to Oxy-Fuel Burners copper anode furnaces • Substantially reduces NOx Summary emissions • Reduces maintenance costs Retrofitting copper smelting applications from air-fuel to oxy-fuel has been shown to lower fuel and plant operating costs and reduce emissions. In 1988, Kennecott Utah Copper upgraded its air-fuel burners to low NOx oxy-fuel burners in its Utah Copper smelter-copper anode furnaces. This project resulted in energy savings of about 55 percent and substantial NOx emission reductions. When Kennecott APPLICATIONS designed its new, state-of-the-art smelter in the early 1990s, it selected oxy-fuel burners for the anode furnaces to achieve low NOx emissions and high energy Experience has shown that retrofitting efficiency. When oxy-fuel burner technology improvements became available in copper smelting anode furnaces from April 2000, Kennecott initiated another project to upgrade to a new design. air-fuel to oxy-fuel burners typically Switching to Dilute Oxygen Combustion (DOC) burners resulted in an additional results in substantially reduced NOx 80 percent reduction in NOx emissions, and improved maintenance costs for the two anode furnaces. emissions as well as 50 to 60 percent fuel savings from eliminating the large Plant/Company Overview nitrogen load associated with air-fired Kennecott Utah Copper, a subsidiary of the international mining and processing combustion. Low-NOx oxy-fuel corporation Rio Tinto, produces approximately 320,000 tons of copper cathode burners have also been commercially demonstrated in steel reheating furnaces. -

John-Sebastien Jacques Chief Executive Officer Rio Tinto and Utah Kennecott Copper Corporation

August 26, 2020 An Open Letter to: John-Sebastien Jacques Chief Executive Officer Rio Tinto and Utah Kennecott Copper Corporation Dear Mr. Jacques: As residents, and civic groups, of the Salt Lake Valley concerned for the health of all residents, we request that Rio Tinto Kennecott place its extensive land holdings in Salt Lake City’s Northwest Quadrant into a permanent conservation easement. Preserving this land would enhance the Kennecott Inland Sea Shorebird Reserve and demonstrate a commitment to public health and environmental sustainability. You currently plan to allow development of this land as part of an inland port. By protecting this area from development, Rio Tinto Kennecott would safeguard our valley from 70,000 additional daily commercial truck trips and 150,000 additional daily private car trips which our modeling suggests would be generated at full build out. Damage to water quality and important wildlife habitat is almost inevitable. Communities near inland ports elsewhere in the United States have suffered serious public health problems. Multiple studies of communities with inland ports elsewhere in the United States cite increases in numerous adverse health outcomes, including heart and lung disease, neurologic disorders, and increased cancer risk. As is the case with much urban environmental degradation, public health impacts fall disproportionately on low-income families and persons of color. Rio Tinto Kennecott’s long history of harming Utah’s environment has required numerous legal actions to end polluting activities. For decades, your operations in western Salt Lake County generated toxic selenium and arsenic groundwater plumes. An acid plume at the southern end of these operations rendered the water undrinkable for thousands of residents of South Jordan. -

David B. Morris Kennecott Corporation

DIGGING OUT: KENNECOTT RESURFACES IN AN ERA OF GLOBAL COMPETITION David B. Morris Kennecott corporation 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. GROWTH, STAGNATION, AND DECLINE 3 origins of Kennecott . 3 Jackling•s New concept •....... 4 Guggenheim Financial Backing . • . 7 Control of the Hill . • . 10 The Jackling organization 12 Genesis of Kennecott copper corporation . 14 Growth Between the wars . • • . 16 over the Hill . • • . • • 19 Allure of Diversification . • 23 Peabody Coal and Anti trust_ . 25 carborundum and its Aftermath 26 Independence Lost 29 III. NEW MANAGEMENT 32 Kennecott Minerals company • 33 Joklik's Long-term Strateav .... 35 The New strategy in Action . 38 IV. COST REDUCTION WITHOUT MAJOR CAPITAL SPENDING 40 Elements of KMC 40 Incremental Cost Reduction 1980-84 • • • . 43 Probing the cost Reduction Frontier in 1980 • 44 Improving Productivity on the Job . • • . 49 Accelerating the Effort in 1981 • • 51 Manpower Reductions in Early 1982 • 53 Shutdowns at Ray and Chino . 56 i Additional 1982 Phases of Cost Reduction 60 consolidatinq the Gains in 1983 and 1984 62 V. WASHINGTON INITIATIVES . 72 Government Controlled Copper Production . 72 Kennecott Initiatives . 74 VI. EVOLUTION OF LABOR RELATIONS . 82 The 1980 Labor contract . 82 A New Approach to Labor Relations 84 Copper Negotiations in 1983 . 91 A Quest for Concessions . 93 The 1986 Labor Contract . 96 Good News, Bad News • 104 VII. MODERNIZATION OF COPPER OPERATIONS . 107 Chino Modernization . 108 Mine and Concentrator . 109 smelter . • . • . • . 112 Utah Copper Modernization . 115 Fundinq in a Depressed Copper Market • . 119 Chanqinq Plans . 12 4 Two More Chanqes of ownership 126 Construction and startup • • . 12 7 Finishinq the Job . -

US Copper Porphyry Mines

U.S. Copper Porphyry Mines Report THE TRACK RECORD OF WATER QUALITY IMPACTS RESULTING FROM PIPELINE SPILLS, TAILINGS FAILURES AND WATER COLLECTION AND TREATMENT FAILURES. JULY 2012 (REVISED 11/2012) TM EARTHWORKS TM EARTHWORKS TM EARTHWORKS TM EARTHWORKS U.S. COPPER PORPHYRY MINES: The track record of water quality impacts resulting from pipeline spills, tailings failures and water collection and treatment failures. EARTHWORKS, July 2012 (Revised 11/2012) By Bonnie Gestring Reviewed by Dave Chambers Ph. D., Center for Science in Public Participation (CSP2) TM EARTHWORKS Photos, top to bottom: TM Yankee Doodle tailings pond by Ecoflight EARTHWORKS Chino Mine by Gila Resource Information Project (GRIP) Sierrita Mine by Ecoflight Bird fatality at Tyrone Mine by Jim Kuipers TM EARTHWORKS TM EARTHWORKS Table of Contents Introduction, Methods, & Results ..................................................................................................... 4 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………………………………5 Table 1: Copper production amounts for mines reviewed in the report ................................... 6 Table 2. Synopsis of pipeline spills, tailings spills and impoundment failures, and water capture and treatment failures for 14 copper porphyry mines (1986-2012). ............... 7 Case Studies of Active U.S. Copper Porphyry Mines Morenci Mine, AZ…………………………………………………………………………………. 8 Bingham Canyon, UT .......................................................................................................... 10 Ray Mine, AZ .......................................................................................................................