'Just Another Start to the Denigration of Anzac Day': Evolving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue

The Women’s Review of Books Vol. XXI, No. 1 October 2003 74035 $4.00 I In This Issue I In Zelda Fitzgerald, biographer Sally Cline argues that it is as a visual artist in her own right that Zelda should be remembered—and cer- tainly not as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s crazy wife. Cover story D I What you’ve suspected all along is true, says essayist Laura Zimmerman—there really aren’t any feminist news commentators. p. 5 I “Was it really all ‘Resilience and Courage’?” asks reviewer Rochelle Goldberg Ruthchild of Nehama Tec’s revealing new study of the role of gender during the Nazi Holocaust. But generalization is impossible. As survivor Dina Abramowicz told Tec, “It’s good that God did not test me. I don’t know what I would have done.” p. 9 I No One Will See Me Cry, Zelda (Sayre) Fitzgerald aged around 18 in dance costume in her mother's garden in Mont- Cristina Rivera-Garza’s haunting gomery. From Zelda Fitzgerald. novel set during the Mexican Revolution, focuses not on troop movements but on love, art, and madness, says reviewer Martha Gies. p. 11 Zelda comes into her own by Nancy Gray I Johnnetta B. Cole and Beverly Guy-Sheftall’s Gender Talk is the Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise by Sally Cline. book of the year about gender and New York: Arcade, 2002, 492 pp., $27.95 hardcover. race in the African American com- I munity, says reviewer Michele Faith ne of the most enduring, and writers of her day, the flapper who jumped Wallace. -

No. 46 Winter 2012

No. 46 Winter 2012 Official publication for Returned & Services League of Australia Tasmanian State Branch (inc.) Corporate Office Bishop Davies Court The Manor Rubicon Grove Umina Park Statewide 28 Davey Street 27 Redwood Road 2 Guy Street 89 Club Drive Mooreville Road Community Hobart Kingston King Meadows Port Sorell Burnie Programs 6220 1200 6283 1100 6345 2101 6427 5700 6433 5166 6345 2124 or visit our website at www.onecare.org.au TheOn Service magazine is produced by the Returned & Services League of Inside this Australia (Tasmania Branch) Inc and issued three times per year. Submissions of articles of around 300 words, with accompanying ISSUE: photographs (in digital format), From the Editorial Desk 2 or items for the Notices section From the Presidents Desk 2 are encouraged. Submissions Chief Executive Officer’s Comment 4 should be emailed to [email protected] Vice President’s Reports 5 or mailed to: State Welfare Coordinator’s Report 7 On Service, RSL (Tasmania Images of ANZAC Day in Hobart 8 Branch), ANZAC House, Navy Crew Suspected of Anglesea Cannon Liberation 10 68 Davey Street DVA Goes Online in Tasmania 10 HOBART Tasmania 7000 VALE Sergeant Blaine Flower Diddams 11 Submissions should be free of personal views, political bias and must be Australian Veterans Honour WWII Airmen 12 of interest to the wider membership of the RSL. Unique Centenary Gift Returns Home 15 Short requests seeking information or contact with ex-Service Boer War Comemorative Day 2012 15 members are welcome for the Notices section. RSL (Tasmania Branch) State Congress 2012 Table of Motions Considered 18 All enquiries relating to On Service may be forwarded to RSL (Tasmania State Congress 2012 20 Branch) Editorial Team of Phil Pyke on 0408 300 148 or to the Chief Executive Officer, Noeleen Lincoln on (03) 6224 0881.” Around The Sub Branches 22 Serving Tasmanians 23 We reserve the right to edit, include or refuse any submission. -

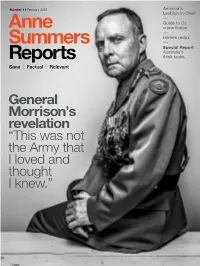

2015 Anne Summers Issue 11 2015

Number 11 February 2015 America’s Lesbian-in-Chief Guide to Oz crime fiction Harlem redux Special Report Australia’s think tanks Sane Factual Relevant General Morrison’s revelation “This was not the Army that I loved and thought I knew.” #11 February 2015 I HOPE YOU ENJOY our first issue for 2015, and our eleventh since we started our digital voyage just over two years ago. We introduce Explore, a new section dealing with ideas, science, social issues and movements, and travel, a topic many of you said, via our readers’ survey late last year, you wanted us to cover. (Read the full results of the survey on page 85.) I am so pleased to be able to welcome to our pages the exceptional mrandmrsamos, the husband-and-wife team of writer Lee Tulloch and photographer Tony Amos, whose piece on the Harlem revival is just a taste of the treats that lie ahead. No ordinary travel writing, I can assure you. Anne Summers We are very proud to publish our first investigative special EDITOR & PUBLISHER report on Australia’s think tanks. Who are they? Who runs them? Who funds them? How accountable are they and how Stephen Clark much influence do they really have? In this landmark piece ART DIRECTOR of reporting, Robert Milliken uncovers how thinks tanks are Foong Ling Kong increasingly setting the agenda for the government. MANAGING EDITOR In other reports, you will meet Merryn Johns, the Australian woman making a splash as a magazine editor Wendy Farley in New York and who happens to be known as America’s Get Anne Summers DESIGNER Lesbian-in-Chief. -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

Item 7.2.1 18 Mckellar Street, South Hobart 46-48 Molle Street, West

APPLICATION UNDER HOBART INTERIM PLANNING SCHEME 2015 Type of Report: Committee Council: 3 December 2018 Expiry Date: 27 December 2018 Application No: PLN18261 Address: 18 MCKELLAR STREET , SOUTH HOBART 46 48 MOLLE STREET , WEST HOBART ADJACENT ROAD RESERVE Applicant: Simon Munn (City of Hobart) 16 Elizabeth Street Proposal: Path Extension and Associated Works and Landscaping Representations: Three (3) Performance criteria: Historic Heritage Code 1. Executive Summary 1.1 Planning approval is sought for Path Extension and Associated Works and Landscaping. Page: 1 of 23 1.2 More specifically the proposal involves the following: The Hobart Rivulet Path currently extends west from the carpark at 4044 Molle Street through Councilowned parkland known as 4648 Molle Street towards the eastern end of McKellar Street. In the vicinity of the eastern end of McKellar Street the path splits a short, relatively steep section of path rises to meet the end of McKellar Street, providing access through to South Hobart, while a flat, deadend section of path leads to the Korean Grove Memorial. Currently, people visiting the Korean Grove Memorial but wanting to reach South Hobart need to retrace their steps along the deadend section of path before rejoining the main Rivulet Path which turns back along McKellar Street. Also, the McKellar Street section of the Hobart Rivulet Path is currently in the form of a narrow, gravel foothpath beside the asphalt street. The proposal is to extend the Hobart Rivulet Path through 18 McKellar Street to Gore Street, so that a continuous pedestrian and bicycle link is formed. -

The Roots and Development of Jewish Feminism in the United States, 1972-Present: a Path Toward Uncertain Equality

Aquila - The FGCU Student Research Journal The Roots and Development of Jewish Feminism in the United States, 1972-Present: A Path Toward Uncertain Equality Jessica Evers Division of Social & Behavioral Sciences, College of Arts & Sciences Faculty mentor: Scott Rohrer, Ph.D., Division of Social & Behavioral Sciences, College of Arts & Sciences ABSTRACT This research project involves discovering the pathway to equality for Jewish women, specifically in Reform Judaism. The goal is to show that the ordination of the first woman rabbi in the United States initiated Jewish feminism, and while this raised awareness, full-equality for Jewish women currently remains unachieved. This has been done by examining such events at the ordination process of Sally Priesand, reviewing the scholarship of Jewish women throughout the waves of Jewish feminism, and examining the perspectives of current Reform rabbis (one woman and one man). Upon the examination of these events and perspectives, it becomes clear that the full-equality of women is a continual struggle within all branches of American Judaism. This research highlights the importance of bringing to light an issue in the religion of Judaism that remains unnoticed, either purposefully or unintentionally by many, inside and outside of the religion. Key Words: Jewish Feminism, Reform Judaism, American Jewish History INTRODUCTION “I am a feminist. That is, I believe that being a woman or a in the 1990s and up to the present. The great accomplishments man is an intricate blend of biological predispositions and of Jewish women are provided here, however, as the evidence social constructions that varies greatly according to time and illustrates, the path towards total equality is still unachieved. -

On the 80Th Anniversary of the Battle of Britain

‘A Gathering of Eagles’ on the 80th Anniversary of the Battle of Britain A National Commemoration of Air Power and Air Forces Hobart, Tasmania 11th - 13th September 2020 INVITATION The Royal Australian Air Force Association, Tasmania Division, extends to all Royal Australian Air Force members, past and present, and their partners and guests an invitation to attend ‘A Gathering of Eagles’ to be held in Hobart over the period Friday 13th - Sunday 15th of September 2019 to commemorate the deeds and sacrifices of the Royal Australian Air Force, the Royal Air Force, Allied and all Air Forces in all conflicts past and present. • WELCOME HAPPY HOUR Friday 11th September at the RAAF Memorial Centre, 61 Davey Street, Hobart - 1700-2130hrs. Drinks and Snacks. Dress: Casual. • REMEMBRANCE SERVICE Saturday 12th September at St David’s Cathedral, 23 Murray Street, Hobart at 1400hrs. Dress: RAAF 1A Uniform or Lounge Suit with full size medals, Day Dress. • DINING IN NIGHT Saturday 12th September at Elwick Park Function Centre - 1900hrs for 1930hrs. Cost $105.00 each all inclusive. Dress: RAAF Winter Mess Dress (with miniatures), Dinner/Lounge Suit, Cocktail/Evening Dress. Guest Speaker: TBC • CENOTAPH SERVICE and WREATH LAYING Sunday 13th September at the Hobart Cenotaph, Queens Domain at 1100hrs. Full size medals. Commemorative Address: TBC • BARBECUE LUNCHEON Sunday 13th September at the RAAF Memorial Centre, 61 Davey Street, Hobart at 1215hrs. (gold coin donation) RAAF SUPPORT The Australian Flying Corps and Royal Australian Air Force Association is most grateful to the Chief of Air Force, for the provision of RAAF support to these commemorative activities. -

Notices of Motion

No. 17 THURSDAY, 30 AUGUST 2018 Notices of Motion 29 Ms Butler to move—That the House:— (1) Notes the Tasmanian Anglican Church has voted to proceed with the Redress Proposal Process, a plan to sell 76 churches to fund contribution towards the Redress Scheme. (2) Acknowledges support for the Redress Scheme. (3) Further notes the significant historical importance of the Quamby Parish Trinity Churches, St Marys Church in Hagley, St Andrews Church in Westbury and St Andrews Church in Carrick all feature on the list of properties that may be sold. (4) Further acknowledges St Marys Church in Hagley built in 1861 by Sir Richard Dry, one of our founding fathers, the first Tasmanian born Premier, Speaker of the House and the first Tasmanian to be knighted. Sir Richard Dry, part of the 'Patriotic six' stopped the transportation of convicts to Tasmania and later introduced mandatory public education. Sir Richard Dry is buried underneath the chancel at St Marys Church Hagley. (5) Further notes St Andrews Church, Westbury hosts the largest collection of works by internationally renowned wood carver Ellen Nora (Nellie) Payne. The magnificent Seven Sisters Screen, church pulpit, prayer desk and alter. (6) Calls upon the Minister of Heritage to stop the closure and sale of the Quamby Parish Churches and other significant historical churches based on their irreplaceable significance to Tasmania's heritage. (12 June 2018) 30 Dr Broad to move—That the House:— (1) Calls upon the Minster for Primary Industries and Water, Hon. Sarah Courtney MP, to immediately establish an expert Fruit Fly Task Force, including government, industry, scientific experts and emergency service personnel, to lead the response to ensure that Tasmania regains our fruit fly free status. -

Asia-Pacific Women in Leadership (Apwil) Workshop 2017

Asia-Pacific Women in Leadership (APWiL) Workshop 2017 This article was first published on the University of Sydney website on https://sydney.edu.au/news- opinion/news/2017/11/06/how-can-we-get-more-gender-diversity-in-university-leadership-.html. How can we get more gender diversity in university leadership? – Accelerating change in gender diversity and inclusion The Association of Pacific Rim Universities (APRU) and University of Sydney co-hosted the 2017 Asia-Pacific Women in Leadership workshop on 1 - 3 November. “Currently, 31 percent of professors at the University are women; our target is to reach 40 percent by 2020.” - Vice-Chancellor and Principal Dr Michael Spence Attendees at the 2017 Asia-Pacific Women in Leadership workshop. The theme of this year’s workshop was ‘Accelerating change in gender diversity and inclusion’, exploring how university leadership can drive culture change through innovation and deliver practical solutions based on best practice. Women are chronically underrepresented in leadership positions at universities in Australia and abroad. A 2013 report by the APRU – which surveyed 45 leading universities in the Asia-Pacific region – found that for every female manager at the university executive management level, there were three males in similar positions. Leadership at Australian universities is similarly skewed towards men, with only one in four vice-chancellors and one in six chancellors a woman. Participants, who came from a variety of universities and public institutions across the Asia-Pacific, were invited to contribute ideas and knowledge to improve the representation of women in senior leadership positions’. The keynote speakers for the opening plenary were Professor Jane Latimer from the University’s School of Public Health and Lieutenant General David Morrison AO, former Chief of Army. -

Mobilising Men and Women to Act in Solidarity for Gender Equality Emina Subašić1, Stephanie L. Hardacre1, Be

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Research Exeter RUNNING HEAD: Solidarity for gender equality “We for She”: Mobilising Men and Women to Act in Solidarity for Gender Equality Emina Subašić1, Stephanie L. Hardacre1, Benjamin Elton1, Nyla R. Branscombe2, Michelle K. Ryan3,4, & Katherine J. Reynolds5 1University of Newcastle, Australia 2Univeristy of Kansas, US 3University of Exeter, UK 4University of Groningen , The Netherlands 5Australian National University In press: Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, Special Issue: “Addressing Gender Inequality” Keywords: gender equality, collective action, social change, solidarity, social identity, feminist identity, leadership, legitimacy RUNNING HEAD/SHORT TITLE: Solidarity for gender equality Please address correspondence to: Emina Subašić [email protected] School of Psychology University of Newcastle Callaghan, NSW 2308 Australia ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: This research was supported by funding from the Australian Research Council (DP1095319). 1 RUNNING HEAD: Solidarity for gender equality Abstract Gender (in)equality is typically studied as a women’s issue to be addressed via systemic measures (e.g., government policy). As such, research focusing on mobilising men (and women) towards achieving gender equality is rare. In contrast, this paper examines the mobilisation of both men and women towards gender equality as common cause. Experiment 1 shows that men’s collective action intentions increase after reading messages that position men as agents of change towards gender equality, compared to messages that frame this issue as stemming from inadequate government policy. Experiments 2 and 3 demonstrate that messages framing gender equality as an issue for both men and women increase men’s collective action intentions, compared to when gender inequality is framed as primarily concerning women. -

Anzac Day 2019 Service Speech by Her Excellency Professor the Honourable Kate Warner Ac Governor of Tasmania Hobart Cenotaph, Thursday 25 April 2019

1 ANZAC DAY 2019 SERVICE SPEECH BY HER EXCELLENCY PROFESSOR THE HONOURABLE KATE WARNER AC GOVERNOR OF TASMANIA HOBART CENOTAPH, THURSDAY 25 APRIL 2019 I begin by paying my respects to the traditional and original owners of this land: the palawa people. I acknowledge the contemporary Tasmanian Aboriginal community, who have survived invasion and dispossession, and continue to maintain their identity, culture and Indigenous rights. Just over three weeks ago on Sunday 31st March, the Bridge of Remembrance, which links the Cenotaph with the Soldiers Memorial Walk on the Domain, was opened. This Centenary of Anzac Day project is be a lasting memory of the 15,000 Tasmanians who enlisted during the First World War, the 2,500 who died as well as all Australians who served during World War I. A central feature of the ceremony was a smoking ceremony and three Indigenous dances. Speaking at the opening, the Minister for Veteran Affairs the Honourable Darren Chester MP, noted that we should remember the Indigenous Australians who served in World War 1 at a time when they were ineligible to vote. The Centenary of Anzac Day with its particular focus on World War 1 provided an opportunity to consider more broadly the effects of war and the contributions and suffering of those who have not always been specifically and sufficiently acknowledged. The contribution of women, for example, and the different ethnic groupings within the Australian imperial force. The Anzac tradition has been increasingly embraced by contemporary Australians but it is a tradition from which our country’s Indigenous people have felt excluded.1 It is pleasing that there have been attempts to address this. -

Anzac Day 25 April 2021

ANZAC DAY 25 APRIL 2021 WE WILL REMEMBER THEM During World War One 416,809 Australians enlisted to serve - many never returned. The Australians displayed great courage, endurance, initiative, discipline and mateship. Such qualities came to be known as the ANZAC spirit. 15,485 Tasmanians enlisted in World War One and today more than 10,500 war veterans and ex-service personnel live in Tasmania. This year is the first ANZAC Day where we recognise Tasmania’s most recent Victoria Cross recipient, Ordinary Seaman Edward “Teddy” Sheean. LEST WE FORGET On 25 April each year we call for Tasmanians to remember the sacrifice of all Australians who served our country. In 2021 ANZAC Day commemorations in Hobart will be held in a modified format. The Dawn Service, the March and the commemorative service at the Hobart Cenotaph are ticketed events with pre-registration required. The March will be for veterans only. No entry will be allowed without a ticket, and the community is encouraged to register early. To register your attendance or for more information contact rsltas.org.au/hobart-anzac-day-commemorations Tasmanians can also commemorate ANZAC Day by: • Tuning in to the Australian War Memorial services on ABC TV, ABC Radio, Facebook and iview. • Taking part in your local commemoration. Details at rsltas.org.au/hobart-anzac-day-commemorations • Watching the Hobart March and commemorative service on ABC TV, iview, and ABC Hobart’s and RSL Tasmania’s Facebook pages from 11.00am. 25 APRIL 2021 5.30am Australian War Memorial Services ABC TV, ABC News Channel, ABC RN, ABC Radio, ABC listen app, ABC Australia Facebook and iview The Australian War Memorial Dawn Service and National Ceremony will be broadcast and livestreamed on ABC TV and ABC online.