An Accident of Memory: Edward Shils, Paul Lazarsfeld and the History of American Mass Communication Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television and the Myth of the Mediated Centre: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Television Studies?

TELEVISION AND THE MYTH OF THE MEDIATED CENTRE: TIME FOR A PARADIGM SHIFT IN TELEVISION STUDIES? Paper presented to Media in Transition 3 conference, MIT, Boston, USA 2-4 May 2003 NICK COULDRY LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE Media@lse London school of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE UK Tel +44 (0)207 955 6243 Fax +44 (0)207 955 7505 [email protected] 1 TELEVISION AND THE MYTH OF THE MEDIATED CENTRE: TIME FOR A PARADIGM SHIFT IN TELEVISION STUDIES? ‘The celebrities of media culture are the icons of the present age, the deities of an entertainment society, in which money, looks, fame and success are the ideals and goals of the dreaming billions who inhabit Planet Earth’ Douglas Kellner, Media Spectacle (2003: viii) ‘The many watch the few. The few who are watched are the celebrities . Wherever they are from . all displayed celebrities put on display the world of celebrities . precisely the quality of being watched – by many, and in all corners of the globe. Whatever they speak about when on air, they convey the message of a total way of life. Their life, their way of life . In the Synopticon, locals watch the globals [whose] authority . is secured by their very remoteness’ Zygmunt Bauman, Globalization: The Human Consequences (1998: 53-54) Introduction There seems to something like a consensus emerging in television analysis. Increasing attention is being given to what were once marginal themes: celebrity, reality television (including reality game-shows), television spectacles. Two recent books by leading media and cultural commentators have focussed, one explicitly and the other implicitly, on the consequences of the ‘supersaturation’ of social life with media images and media models (Gitlin, 2001; cf Kellner, 2003), of which celebrity, reality TV and spectacle form a taken-for-granted part. -

ELITES, POWER SOURCES and DEMOCRACY by DENZ YETKN

ELITES, POWER SOURCES AND DEMOCRACY by DEN İZ YETK İN Submitted to the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University 2008 ELITES, POWER SOURCES AND DEMOCRACY APPROVED BY: Asst. Prof. Dr.Nedim Nomer: ……………………. (Dissertation Supervisor) Prof. Sabri Sayarı: ……………………. Prof. Tülay Artan: ……………………. DATE OF APPROVAL: …………………… To my parents... © Deniz Yetkin 2008 All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………vi Abstract...……………………………………………………………………………..…vii Özet…….……………………………………………………………………………….viii INTRODUCTION .…………………………………………………….......…………....1 CHAPTER 1..……………………………………………………………………………6 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF ELITE DISCUSSION 1.1 Machiavelli and His Followers……………………………………………....7 1.2 The Classical Elite Theorists……………………………………………......8 1.2.1 Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923) and the ‘Governing Elite’…………..…….....8 1.2.2 Gaetano Mosca (1858- 1941) and the ‘Ruling Class’……….………...….21 1.2.3 Robert Michels (1876-1936) and the ‘Dominant Class’……………...…..23 1.2.4 C. Wright Mills (1916-1962) and ‘The Power Elite’………..……………26 1.3 Who are Elites? ……………………………………………………………30 CHAPTER 2 ..……………………………………………………………….………….32 POWER SOURCES, POWER SCOPE OF ELITES, AND THE POSSIBILITY OF DEMOCRACY 2.1 Power and Democracy in Classical Elite Theories...……………………….33 2.2. A New Approach to Elites, Power Sources and Democracy...…………….38 CONCLUSION ..……………………………………………………………………….47 BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………………………………………….……..49 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor Asst. Prof. Nedim Nomer. I believe that without his support and guidance the writing of this thesis would have been difficult. Moreover, I am grateful to Prof. Sabri Sayarı and Prof. Tülay Artan for their precious comments. Apart from academic realm, I also would like to thank all my friends: I am grateful to my friends at Sabancı University for making my study enjoyable. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY 2002 DirecTV DSL “End of the Internet” Commercial. Accessed March 5, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch? v5_uXtWIg_A7M. Adorno, Theodor W. “The Form of the Phonograph Record.” In Essays on Music/Theodor W. Adorno, edited by Theodor W. Adorno, Richard D. Leppert, and Susan H. Gillespie, 277–80. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. Agger, Ben. Fast Capitalism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988. Agger, Ben. Speeding Up Fast Capitalism: Cultures, Jobs, Families, Schools, Bodies. Boulder: Routledge, 2004. Agger, Ben. Oversharing: Presentations of Self in the Internet Age. New York: Routledge, 2011. Aglietta, Michel. A Theory of Capitalist Regulation: The US Experience. Translated by David Fernbach. New edition. New York: Verso, 2001. Allen, Jennifer. “How Episode Became the World’s Biggest Interactive Fiction Platform.” Accessed August 7, 2020. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/293928/How_Episode_ became_the_worlds_biggest_interactive_fiction_platform.php. 151 152 Bibliography Andrejevic, Mark. Infoglut: How Too Much Information Is Changing the Way We Think and Know. 1st ed. New York: Routledge, 2013. Arditi, David. “Billboard Plays Catch-up to YouTube’s Dominance.” The Tennessean. March 9, 2020, Online edition, sec. Opinion. https://www.tennessean.com/story/ opinion/2020/03/09/billboard-catches-up-to-youtube- dominance/5005889002/. Arditi, David. Criminalizing Independent Music: The Recording Industry Association of America’s Advancement of Dominant Ideology. VDM Verlag, 2007. Arditi, David. “Downloading Is Killing Music: The Recording Industry’s Piracy Panic Narrative.” Edited by Victor Sarafian and Rosemary Findley. Civilisations, The State of the Music Industry, 63, no. 1 (July 2014): 13–32. Arditi, David. ITake-Over: The Recording Industry in the Digital Era. -

The Revival of Economic Sociology

Chapter 1 The Revival of Economic Sociology MAURO F. G UILLEN´ , RANDALL COLLINS, PAULA ENGLAND, AND MARSHALL MEYER conomic sociology is staging a comeback after decades of rela- tive obscurity. Many of the issues explored by scholars today E mirror the original concerns of the discipline: sociology emerged in the first place as a science geared toward providing an institutionally informed and culturally rich understanding of eco- nomic life. Confronted with the profound social transformations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the founders of so- ciological thought—Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, Georg Simmel—explored the relationship between the economy and the larger society (Swedberg and Granovetter 1992). They examined the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services through the lenses of domination and power, solidarity and inequal- ity, structure and agency, and ideology and culture. The classics thus planted the seeds for the systematic study of social classes, gender, race, complex organizations, work and occupations, economic devel- opment, and culture as part of a unified sociological approach to eco- nomic life. Subsequent theoretical developments led scholars away from this originally unified approach. In the 1930s, Talcott Parsons rein- terpreted the classical heritage of economic sociology, clearly distin- guishing between economics (focused on the means of economic ac- tion, or what he called “the adaptive subsystem”) and sociology (focused on the value orientations underpinning economic action). Thus, sociologists were theoretically discouraged from participating 1 2 The New Economic Sociology in the economics-sociology dialogue—an exchange that, in any case, was not sought by economists. It was only when Parsons’s theory was challenged by the reality of the contentious 1960s (specifically, its emphasis on value consensus and system equilibration; see Granovet- ter 1990, and Zelizer, ch. -

In This Issue

The Women’s Review of Books Vol. XXI, No. 1 October 2003 74035 $4.00 I In This Issue I In Zelda Fitzgerald, biographer Sally Cline argues that it is as a visual artist in her own right that Zelda should be remembered—and cer- tainly not as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s crazy wife. Cover story D I What you’ve suspected all along is true, says essayist Laura Zimmerman—there really aren’t any feminist news commentators. p. 5 I “Was it really all ‘Resilience and Courage’?” asks reviewer Rochelle Goldberg Ruthchild of Nehama Tec’s revealing new study of the role of gender during the Nazi Holocaust. But generalization is impossible. As survivor Dina Abramowicz told Tec, “It’s good that God did not test me. I don’t know what I would have done.” p. 9 I No One Will See Me Cry, Zelda (Sayre) Fitzgerald aged around 18 in dance costume in her mother's garden in Mont- Cristina Rivera-Garza’s haunting gomery. From Zelda Fitzgerald. novel set during the Mexican Revolution, focuses not on troop movements but on love, art, and madness, says reviewer Martha Gies. p. 11 Zelda comes into her own by Nancy Gray I Johnnetta B. Cole and Beverly Guy-Sheftall’s Gender Talk is the Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise by Sally Cline. book of the year about gender and New York: Arcade, 2002, 492 pp., $27.95 hardcover. race in the African American com- I munity, says reviewer Michele Faith ne of the most enduring, and writers of her day, the flapper who jumped Wallace. -

Marital and Familial Roles on Television: an Exploratory Sociological Analysis Charles Daniel Fisher Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1974 Marital and familial roles on television: an exploratory sociological analysis Charles Daniel Fisher Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Charles Daniel, "Marital and familial roles on television: an exploratory sociological analysis " (1974). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5984. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5984 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Giants: the Global Power Elite

Secrecy and Society ISSN: 2377-6188 Volume 2 Number 2 Teaching Secrecy Article 13 January 2021 Giants: The Global Power Elite Susan Maret San Jose State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/secrecyandsociety Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Other Sociology Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public olicyP and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Maret, Susan. 2021. "Giants: The Global Power Elite." Secrecy and Society 2(2). https://doi.org/10.31979/2377-6188.2021.020213 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/ secrecyandsociety/vol2/iss2/13 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Information at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Secrecy and Society by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Giants: The Global Power Elite Keywords human rights, C. Wright Mills, openness, power elite, secrecy, transnational corporations, transparency This book review is available in Secrecy and Society: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/ secrecyandsociety/vol2/iss2/13 Maret: Giants: The Global Power Elite Review, Giants: The Global Power Elite by Peter Philips Reviewed by Susan Maret Giants: The Global Power Elite, New York: Seven Stories Press, 2018. 384pp. / ISBN: 9781609808716 (paperback) / ISBN: 9781609808723 (ebook) https://www.sevenstories.com/books/4097-giants The strength of Giants: The Global Power Elite lies in its heavy documentation of the "globalized power elite, [a] concept of the Transnationalist Capitalist Class (TCC), theorized in the academic literature for some twenty years" (Phillips 2018, 9). -

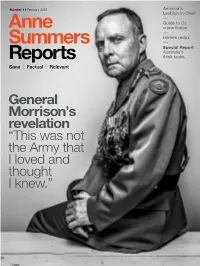

2015 Anne Summers Issue 11 2015

Number 11 February 2015 America’s Lesbian-in-Chief Guide to Oz crime fiction Harlem redux Special Report Australia’s think tanks Sane Factual Relevant General Morrison’s revelation “This was not the Army that I loved and thought I knew.” #11 February 2015 I HOPE YOU ENJOY our first issue for 2015, and our eleventh since we started our digital voyage just over two years ago. We introduce Explore, a new section dealing with ideas, science, social issues and movements, and travel, a topic many of you said, via our readers’ survey late last year, you wanted us to cover. (Read the full results of the survey on page 85.) I am so pleased to be able to welcome to our pages the exceptional mrandmrsamos, the husband-and-wife team of writer Lee Tulloch and photographer Tony Amos, whose piece on the Harlem revival is just a taste of the treats that lie ahead. No ordinary travel writing, I can assure you. Anne Summers We are very proud to publish our first investigative special EDITOR & PUBLISHER report on Australia’s think tanks. Who are they? Who runs them? Who funds them? How accountable are they and how Stephen Clark much influence do they really have? In this landmark piece ART DIRECTOR of reporting, Robert Milliken uncovers how thinks tanks are Foong Ling Kong increasingly setting the agenda for the government. MANAGING EDITOR In other reports, you will meet Merryn Johns, the Australian woman making a splash as a magazine editor Wendy Farley in New York and who happens to be known as America’s Get Anne Summers DESIGNER Lesbian-in-Chief. -

Editors Ece KARADOĞAN DORUK, Seda MENGÜ, Ebru ULUSOY

DIGITAL SIEGE Editors Ece KARADOĞAN DORUK, Seda MENGÜ, Ebru ULUSOY DIGITAL SEIGE EDITORS Ece KARADOĞAN DORUK Istanbul University, Faculty of Communication, Istanbul, Turkey Seda MENGÜ Istanbul University, Faculty of Political Sciences, Istanbul, Turkey Ebru ULUSOY Farmingdale State College, New York, USA Published by Istanbul University Press Istanbul University Central Campus IUPress Office, 34452 Beyazıt/Fatih Istanbul - Turkey www.iupress.istanbul.edu.tr Digital Seige Editors: Ece Karadoğan Doruk, Seda Mengü, Ebru Ulusoy E-ISBN: 978-605-07-0764-9 DOI: 10.26650/B/SS07.2021.002 Istanbul University Publication No: 5281 Published Online in April, 2021 It is recommended that a reference to the DOI is included when citing this work. This work is published online under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ This work is copyrighted. Except for the Creative Commons version published online, the legal exceptions and the terms of the applicable license agreements shall be taken into account. ii EDITORS Prof. Dr. Ece Karadoğan Doruk Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr. Seda Mengü Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ebru Ulusoy Farmingdale State College, New York, USA ADVISORY BOARD Prof. Dr. Celalettin Aktaş Istanbul Commerce University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr. Füsun Alver Istanbul Commerce University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr. M. Bilal Arık Aydin Adnan Menderes University, Aydin, Turkey Prof. Dr. Oya Şaki Aydın Istanbul Commerce University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr. Aysel Aziz Istanbul Yeni Yüzyıl University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. Dr. Güven N. Büyükbaykal Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. -

Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 12-2008 Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Jefferson Pooley Muhlenberg College Elihu Katz University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pooley, J., & Katz, E. (2008). Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research. Journal of Communication, 58 (4), 767-786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00413.x This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/269 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Further Notes on Why American Sociology Abandoned Mass Communication Research Abstract Communication research seems to be flourishing, as vidente in the number of universities offering degrees in communication, number of students enrolled, number of journals, and so on. The field is interdisciplinary and embraces various combinations of former schools of journalism, schools of speech (Midwest for ‘‘rhetoric’’), and programs in sociology and political science. The field is linked to law, to schools of business and health, to cinema studies, and, increasingly, to humanistically oriented programs of so-called cultural studies. All this, in spite of having been prematurely pronounced dead, or bankrupt, by some of its founders. Sociologists once occupied a prominent place in the study of communication— both in pioneering departments of sociology and as founding members of the interdisciplinary teams that constituted departments and schools of communication. In the intervening years, we daresay that media research has attracted rather little attention in mainstream sociology and, as for departments of communication, a generation of scholars brought up on interdisciplinarity has lost touch with the disciplines from which their teachers were recruited. -

MEDIA REPORT Changing Perceptions Through Television, the Rise of Social Media and Our Media Adventure in the Last Decade 2008 - 2018

KONDA MEDIA REPORT Changing Perceptions Through Television, The Rise of Social Media and Our Media Adventure in the Last Decade 2008 - 2018 November 2019 KONDA Lifestyle Survey 2018 2 / 76 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 2. CHANGING PERCEPTIONS THROUGH TELEVISION AND OUR DECENNIAL MEDIA ADVENTURE .......................................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Relations with Technology / Internet Perception / Concern About Social Media ......... 7 2.2. Trust in Television News ................................................................................................ 11 2.3. Closed World Perception and Echo Chamber............................................................... 19 2.4. The State of Being a Television Society and Changing Perceptions ........................... 20 2.5. Our Changing World Perception Based on the Cultivation Theory .............................. 22 3. SOCIAL MEDIA USAGE IN THE LAST DECADE ............................................................. 27 4. CONCLUSION .............................................................................................................. 29 5. BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 31 6. RESEARCH ID ............................................................................................................. -

The Email Is Down!

Today it is hard to imagine daily communication with out email file:///Q:/TechSvcs/MOspace/MOspace%20content/School%20of%20Jo... The E-mail is Down! Using a 1940s Method to Analyze a 21 st Century Problem by Clyde H. Bentley Associate Professor Missouri School of Journalism University of Missouri and Brooke Fisher Master’s Student Missouri School of Journalism University of Missouri 181D Gannett Hall Columbia, MO 65211-1200 (573) 884-9699 [email protected] \ Presented to the Communications Technology and Policy Division AEJMC 2002 Annual Convention Miami Beach, Florida Aug. 7-10, 2000 1 of 19 2/19/2009 1:31 PM Today it is hard to imagine daily communication with out email file:///Q:/TechSvcs/MOspace/MOspace%20content/School%20of%20Jo... The E-mail is Down! Using a 1940s method to analyze a 21 st century problem Abstract When the electronic mail system at a university crashed, researchers turned to a methodology developed more than 50 years earlier to examine its impact. Using a modified version of Bernard Berelson “missing the newspaper” survey questionnaire, student researchers collected qualitative comments from 85 faculty and staff members. Like the original, the study found extensive anxiety over the loss of the information source, plus a high degree of habituation and dependence on the new medium. 2 of 19 2/19/2009 1:31 PM Today it is hard to imagine daily communication with out email file:///Q:/TechSvcs/MOspace/MOspace%20content/School%20of%20Jo... The E-mail is Down! Using a 1940s Method to Analyze a 21 st Century Problem It seldom puts lives at risk and almost always is accompanied by viable alternatives.