The Elliston Incident

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS PLAN 2021-2030 Ii CITY of PORT LINCOLN – Strategic Directions Plan CONTENTS

CITY OF PORT LINCOLN STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS PLAN 2021-2030 ii CITY OF PORT LINCOLN – Strategic Directions Plan CONTENTS 1 FOREWORD 2 CITY PROFILE 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY 5 COMMUNITY ASPIRATIONS 6 VISION, MISSION and VALUES 8 GOAL 1. ECONOMIC GROWTH AND OPPORTUNITY 10 GOAL 2. LIVEABLE AND ACTIVE COMMUNITIES 12 GOAL 3. GOVERNANCE AND LEADERSHIP 14 GOAL 4. SUSTAINABLE ENVIRONMENT 16 GOAL 5. COMMUNITY ASSETS AND PLACEMAKING 18 MEASURING OUR SUCCESS 20 PLANNING FRAMEWORK 21 COUNCIL PLANS Prepared by City of Port Lincoln Adopted by Council 14 December 2020 RM: FINAL2020 18.80.1.1 City of Port Lincoln images taken by Robert Lang Photography FOREWORD On behalf of the City of Port Lincoln I am pleased to present the City's Strategic Directions Plan 2021-2030 which embodies the future aspirations of our City. This Plan focuses on and shares the vision and aspirations for the future of the City of Port Lincoln. The Plan outlines how, over the next ten years, we will work towards achieving the best possible outcomes for the City, community and our stakeholders. Through strong leadership and good governance the Council will maintain a focus on achieving the Vision and Goals identified in this Plan. The Plan defines opportunities for involvement of the Port Lincoln community, whether young or old, business people, community groups and stakeholders. Our Strategic Plan acknowledges the natural beauty of our environment and recognises the importance of our natural resources, not only for our community well-being and identity, but also the economic benefits derived through our clean and green qualities. -

Eyre Peninsula Local Government Association

EYRE PENINSULA LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION Minutes of the Eyre Peninsula Local Government Association Board Meetingheld at Whyalla Regional Development Australia Board Room, 127 Nicholson Avenue, WhyallaNorrie on Friday7th December 2012, commencing at 10.30am. BOARD MEMBERS PRESENT Julie Low (Chair) President, EPLGA Roger Nield Mayor, District Council of Cleve Eddie Elleway Mayor, District Council of Franklin Harbour Tim Scholz Chairperson, Wudinna District Council Pat Clark Chairperson, District Council of Elliston Bruce Green Mayor, City of Port Lincoln Jim Pollock Mayor, City of Whyalla John Schaefer Mayor, District Council of Kimba Laurie Collins Mayor, District Council of Tumby Bay GUESTS / OBSERVERS Faye Davis Councillor, City of Port Lincoln Adam Gray Director, LGA SA Merton Hodge Councillor, Whyalla City Council Kevin May Region 6 Commander, CFS Richard Bingham Ombudsman SA Jodie Jones District Council of Cleve Peter Arnold CEO, District Council of Cleve Murray Mason Deputy Mayor, District Council of Tumby Bay Tony Irvine CEO, District Council of Tumby Bay Andrea Jorgensen Chief Project Officer, DPTI Donna Ferretti DPTI Terry Barnes CEO, District Council of Franklin Harbour Gavin Jackson D/Mayor, District Council of Franklin Harbour Peter Peppin CEO, City of Whyalla Deb Larwood A/CEO, District Council of Kimba Annie Lane Eyre Peninsula NRM Dean Johnson Deputy Mayor, District Council of Kimba Peter Hall DMITRE Josh Zugger Electranet Scott Haynes Electranet Rod Pearson CEO, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula Diana Laube Executive -

Strategic Plan 2016 - 2025

DISTRICT COUNCIL OF LOWER EYRE PENINSULA Strategic Plan 2016 - 2025 “Working with our Rural & Coastal Communities” Table of Contents Message from the Mayor and Chief Executive Officer ................................ 1 Our Council District .................................................................................... 3 Demographic of District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula .......................... 4 Elected Member Makeup at Adoption of Strategic Plan ............................. 5 District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula – Organisational Chart ................ 6 Strategic Planning ....................................................................................... 7 Strategic Plan Legislative Matters............................................................... 8 Structure of the Strategic Plan ................................................................. 12 INFRASTRUCTURE AND SERVICES ........................................................................ 13 COMMUNITY WELLBEING ................................................................................... 15 ECONOMIC .......................................................................................................... 18 RESPONSIBLE GOVERNANCE ............................................................................... 21 STATUTORY ......................................................................................................... 23 Appendix A – Capital Works Program ....................................................... 25 OUR VISION: To promote -

Annual Business Plan for the Year Ended 30 June 2020

CitCyit ofy ofPo Prto Lrtin Lcinolnco ln AnnAnnualual Bus Binuseinsse ssPlan Pl an2016 201/290/217020 Draft Annual Business Plan For the year ended 30 June 2020 Adopted for Consultation 20 May 2019 RM: N20194028 18.80.2.8 18.80.2.8.N:\Scan\Lynne ABP .2019Jolley-20\18.80.1.6 Draft Adopted ABP 2016-17 20160620.docx 12 | P a g e City of Port Lincoln Annual Business Plan 2019/2020 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 3 2. CONTEXT STATEMENT ................................................................................................................................ 4 Our Place ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Our Community ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Our Vitality and Growth ......................................................................................................................... 4 3. OUR LONG TERM OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................... 5 4. LONG TERM FINANCIAL STRATEGY............................................................................................................. 6 Financial Ratios ..................................................................................................................................... -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

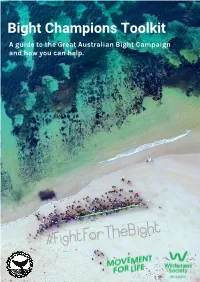

Bight Champions Toolkit a Guide to the Great Australian Bight Campaign and How You Can Help

Bight Champions Toolkit A guide to the Great Australian Bight Campaign and how you can help. Contents Great Australian Bight Campaign in a nutshell 2 Our Vision 2 Who is the Great Australian Bight Alliance? 3 Bight Campaign Background 4 A Special Place 5 The Risks 6 Independent oil spill modelling 6 Quick Campaign Snapshot 7 What do we want? 8 What you can do 9 Get the word out there 10 How to be heard 11 Writing it down 12 Comments on articles 13 Key Messages 14 Media Archives 15 Screen a film 16 Host a meet-up 18 Setting up a group 19 Contacting Politicians 20 Become a leader 22 Get in contact 23 1 Bight campaign in a nutshell THE PLACE, THE RISKS AND HOW WE SAVE IT “ The Great Australian Bight is a body of coast Our vision for the Great and water that stretches across much of Australian Bight is for a southern Australia. It’s an incredible place, teaming with wildlife, remote and unspoiled protected marine wilderness areas, as well as being home to vibrant and thriving coastal communities. environment, where marine The Bight has been home to many groups of life is safe and healthy. Our Aboriginal People for tens of thousands of years. The region holds special cultural unspoiled waters must be significance, as well as important resources to maintain culture. The cliffs of the Nullarbor are valued and celebrated. Oil home to the Mirning People, who have a special spills are irreversible. We connection with the whales, including Jidarah/Jeedara, the white whale and creation cannot accept the risk of ancestor. -

EPLGA Draft Minutes 4 Sep 15.Docx 1

Minutes of the Eyre Peninsula Local Government Association Board Meeting held at Wudinna Community Club on Friday 4 September 2015 commencing at 10.10am. Delegates Present: Bruce Green (Chair) President, EPLGA Roger Nield Mayor, District Council of Cleve Allan Suter Mayor, District Council of Ceduna Kym Callaghan Chairperson, District Council of Elliston Eddie Elleway Councillor, District Council of Franklin Harbour Dean Johnson Mayor, District Council of Kimba Julie Low Mayor, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula Neville Starke Deputy Mayor, City of Port Lincoln Sherron MacKenzie Mayor District Council of Streaky Bay Sam Telfer Mayor District Council of Tumby Bay Tom Antonio Deputy Mayor, City of Whyalla Eleanor Scholz Chairperson, Wudinna District Council Guests/Observers: Tony Irvine Executive Officer, EPLGA Geoffrey Moffatt CEO, District Council of Ceduna Peter Arnold CEO, District Council of Cleve Phil Cameron CEO, District Council of Elliston Dave Allchurch Councillor, District Council of Elliston Eddie Elleway Councillor, District Council of Franklin Harbour Daryl Cearns CEO, District Council of Kimba Debra Larwood Manager Corporate Services, District Council of Kimba Leith Blacker Acting CEO, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula Rob Donaldson CEO, City of Port Lincoln Chris Blanch CEO, District Council of Streaky Bay Trevor Smith CEO, District Council of Tumby Bay Peter Peppin CEO, City of Whyalla Adam Gray Director, Environment, LGA of SA Matt Pinnegar CEO, LGA of SA Jo Calliss Regional Risk Coordinator, Western Eyre -

Monuments and Memorials

RGSSA Memorials w-c © RGSSA Memorials As at 13-July-2011 RGSSA Sources Commemorating Location Memorial Type Publication Volume Page(s) Comments West Terrace Auld's headstone refurbished with RGSSA/ACC Auld, William Patrick, Grave GeoNews Geonews June/July 2009 24 Cemetery Grants P Bowyer supervising Plaque on North Terrace façade of Parliament House unveiled by Governor Norrie in the Australian Federation Convention Adelaide, Parliament Plaque The Proceedings (52) 63 presences of a representative gathering of Meeting House, descendants of the 1897 Adelaide meeting - inscription Flinders Ranges, Depot Society Bicentenary project monument and plaque Babbage, B.H., Monument & Plaque Annual Report (AR 1987-88) Creek, to Babbage and others Geonews Unveiled by Philip Flood May 2000, Australian Banks, Sir Joseph, Lincoln Cathedral Wooden carved plaque GeoNews November/December 21 High Commissioner 2002 Research for District Council of Encounter Bay for Barker, Captain Collett, Encounter bay Memorial The Proceedings (38) 50 memorial to the discovery of the Inman River Barker, Captain Collett, Hindmarsh Island Tablet The Proceedings (30) 15-16 Memorial proposed on the island - tablet presented Barker, Captain Collett, Hindmarsh Island Tablet The Proceedings (32) 15-16 Erection of a memorial tablet K. Crilly 1997 others from 1998 Page 1 of 87 Pages - also refer to the web indexes to GeoNews and the SA Geographical Journal RGSSA Memorials w-c © RGSSA Memorials As at 13-July-2011 RGSSA Sources Commemorating Location Memorial Type Publication Volume -

Place Names of South Australia: W

W Some of our names have apparently been given to the places by drunken bushmen andfrom our scrupulosity in interfering with the liberty of the subject, an inflection of no light character has to be borne by those who come after them. SheaoakLog ispassable... as it has an interesting historical association connectedwith it. But what shall we say for Skillogolee Creek? Are we ever to be reminded of thin gruel days at Dotheboy’s Hall or the parish poor house. (Register, 7 October 1861, page 3c) Wabricoola - A property North -East of Black Rock; see pastoral lease no. 1634. Waddikee - A town, 32 km South-West of Kimba, proclaimed on 14 July 1927, took its name from the adjacent well and rock called wadiki where J.C. Darke was killed by Aborigines on 24 October 1844. Waddikee School opened in 1942 and closed in 1945. Aboriginal for ‘wattle’. ( See Darke Peak, Pugatharri & Koongawa, Hundred of) Waddington Bluff - On section 98, Hundred of Waroonee, probably recalls James Waddington, described as an ‘overseer of Waukaringa’. Wadella - A school near Tumby Bay in the Hundred of Hutchison opened on 1 July 1914 by Jessie Ormiston; it closed in 1926. Wadjalawi - A tea tree swamp in the Hundred of Coonarie, west of Point Davenport; an Aboriginal word meaning ‘bull ant water’. Wadmore - G.W. Goyder named Wadmore Hill, near Lyndhurst, after George Wadmore, a survey employee who was born in Plymouth, England, arrived in the John Woodall in 1849 and died at Woodside on 7 August 1918. W.R. Wadmore, Mayor of Campbelltown, was honoured in 1972 when his name was given to Wadmore Park in Maryvale Road, Campbelltown. -

1218571858.Pdf

No. 12. ------ --/-. -------C I-IETtF:-lS it is espcdient to the Act No.-. 10 of 1855-6, " 'l'u provide for the Election of' Rlvnlbcrs tu serve in thc Par- liamcnt of South Australia," and ihc Act E (?. 8 of .l$!?(jj'' To nrrlend an Act to provide for the election of JZcmbers to wlvc in he Parliament of Sout h hustralia,"also the Act No. 32 of lH55-fi "'hmake ft~rtherp-o- vision for the elcctioa of Mcnlbcrs toC--- sc~vSGZFZP8rliitmcnt of South Australia: " Be it therefore Enacted, by the C+ovcrnor-in-Chief of the Province of South Austrdin, with thc advice and curlsent of the 1,egislatiue C:ouncil and House of Assembly of the said Province, ill this yreserlt Yarliarncrlt assemblcrl, as follows- 1. From and after the passing of this Act the three before-mentioned- -- Nos. load32,1865- 6 &H/- and No. 8, 1856, Acts, shall bc a1111 the same are hereby rep~ale~rxceptin su far as rtpalrd. *4 ()I QLA the same may rcpcd my Act or part of' any Act. 2. For the pnrposc of clccting Mernhcrs of the I&slative C'oimcil, Pmvinc r to form one the said Yroviuce shall forin one clcctoral district ; arid thc S- ckctoral districts specilicd in Schedule ~;~rthk~ct%ncxcd,shall Housc: ui Assembly. form elpctoral divisions--- - of such di~trict; and for the pq~oseof dcctin,o Nembrrs of the Eowe of :',ss~rnhly, the anid Pmviii~hall be divldcd into scoent6 rlectoral clistrklii, nhich shall haw tllc nam& and bou~iclurics,and shall ret1u.n the number uf Members spccificd in the said Sch~ihde. -

Aboriginal/ European Interactions and Frontier Violence on the Western

the space of conflict: Aboriginal/ European interactions and frontier violence on the western Central murray, south Australia, 1830–41 Heather Burke, Amy Roberts, Mick Morrison, Vanessa Sullivan and the River Murray and Mallee Aboriginal Corporation (RMMAC) Colonialism was a violent endeavour. Bound up with the construction of a market-driven, capitalist system via the tendrils of Empire, it was intimately associated with the processes of colonisation and the experiences of exploiting the land, labour and resources of the New World.1 All too often this led to conflict, particularly between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. Overt violence (the euphemistic ‘skirmishes’, ‘affrays’ and ‘collisions’ of the documentary record), clandestine violence (poisonings, forced removals, sexual exploitation and disease) and structural violence (the compartmentalisation of Aboriginal people through processes of race, governance and labour) became routinised aspects of colonialism, buttressed by structures of power, inequality, dispossession and racism. Conflict at the geographical margins of this system was made possible by the general anxieties of life at, or beyond, the boundaries of settlement, closely associated with the normalised violence attached to ideals of ‘manliness’ on the frontier.2 The ‘History Wars’ that ignited at the turn of the twenty-first century sparked an enormous volume of detailed research into the nature and scale of frontier violence across Australia. Individual studies have successfully canvassed the 1 Silliman 2005. 2 -

Aboriginal History Journal: Volume 21

Aboriginal History Volume twenty-one 1997 Aboriginal History Incorporated The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Secretary), Peter Grimshaw (Treasurer/Public Officer), Neil Andrews, Richard Baker, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Luise Hercus, Bill Humes, Ian Keen, David Johnston, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Diane Smith, Elspeth Young. Correspondents Jeremy Beckett, Valerie Chapman, Ian Clark, Eve Fesl, Fay Gale, Ronald Lampert, Campbell Macknight, Ewan Morris, John Mulvaney, Andrew Markus, Bob Reece, Henry Reynolds, Shirley Roser, Lyndall Ryan, Bruce Shaw, Tom Stannage, Robert Tonkinson, James Urry. Aboriginal History aims to present articles and information in the field of Australian ethnohistory, particularly in the post-contact history of the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia will be welcomed. Issues include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, resumes of current events, archival and bibliographical articles, and book reviews. Editors 1997 Rob Paton and Di Smith, Editors, Luise Hercus, Review Editor and Ian Howie Willis, Managing Editor. Aboriginal History Monograph Series Published occasionally, the monographs present longer discussions or a series of articles on single subjects of contemporary interest. Previous monograph titles are D. Barwick, M. Mace and T. Stannage (eds), Handbook of Aboriginal and Islander History; Diane Bell and Pam Ditton, Law: the old the nexo; Peter Sutton, Country: Aboriginal boundaries and land ownership in Australia; Link-Up (NSW) and Tikka Wilson, In the Best Interest of the Child? Stolen children: Aboriginal pain/white shame, Jane Simpson and Luise Hercus, History in Portraits: biographies of nineteenth century South Australian Aboriginal people.