Aboriginal/ European Interactions and Frontier Violence on the Western

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articles and Books About Western and Some of Central Nsw

Rusheen’s Website: www.rusheensweb.com ARTICLES AND BOOKS ABOUT WESTERN AND SOME OF CENTRAL NSW. RUSHEEN CRAIG October 2012. Last updated: 20 March 2013 Copyright © 2012 Rusheen Craig Using the information from this document: Please note that the research on this web site is freely provided for personal use only. Site users have the author's permission to utilise this information in personal research, but any use of information and/or data in part or in full for republication in any printed or electronic format (regardless of commercial, non-commercial and/or academic purpose) must be attributed in full to Rusheen Craig. All rights reserved by Rusheen Craig. ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Wentworth Combined Land Sales Copyright © 2012 Rusheen Craig 1 Contents THE EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT OF THE WESTERN PLAINS. ...................................................... 6 Exploration of the Bogan. ................................................................................................................................... 6 Roderick Mitchell on the Darling. ...................................................................................................................... 7 Exploration of the Country between the Lachlan and the Darling ...................................................................... 7 Occupation of the Country. ................................................................................................................................ 8 Occupation -

Upper Riccarton Cemetery 2007 1

St Peter’s, Upper Riccarton, is the graveyard of owners and trainers of the great horses of the racing and trotting worlds. People buried here have been in charge of horses which have won the A. J. C. Derby, the V.R.C. Derby, the Oaks, Melbourne Cup, Cox Plate, Auckland Cup (both codes), New Zealand Cup (both codes) and Wellington Cup. Area 1 Row A Robert John Witty. Robert John Witty (‘Peter’ to his friends) was born in Nelson in 1913 and attended Christchurch Boys’ High School, College House and Canterbury College. Ordained priest in 1940, he was Vicar of New Brighton, St. Luke’s and Lyttelton. He reached the position of Archdeacon. Director of the British Sailors’ Society from 1945 till his death, he was, in 1976, awarded the Queen’s Service Medal for his work with seamen. Unofficial exorcist of the Anglican Diocese of Christchurch, Witty did not look for customers; rather they found him. He said of one Catholic lady: “Her priest put her on to me; they have a habit of doing that”. Problems included poltergeists, shuffling sounds, knockings, tapping, steps tramping up and down stairways and corridors, pictures turning to face the wall, cold patches of air and draughts. Witty heard the ringing of Victorian bells - which no longer existed - in the hallway of St. Luke’s vicarage. He thought that the bells were rung by the shade of the Rev. Arthur Lingard who came home to die at the vicarage then occupied by his parents, Eleanor and Archdeacon Edward Atherton Lingard. In fact, Arthur was moved to Miss Stronach’s private hospital where he died on 23 December 1899. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 112 Monday, 3 September 2007 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

6835 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 112 Monday, 3 September 2007 Published under authority by Government Advertising SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT EXOTIC DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACT 1991 ORDER - Section 15 Declaration of Restricted Areas – Hunter Valley and Tamworth I, IAN JAMES ROTH, Deputy Chief Veterinary Offi cer, with the powers the Minister has delegated to me under section 67 of the Exotic Diseases of Animals Act 1991 (“the Act”) and pursuant to section 15 of the Act: 1. revoke each of the orders declared under section 15 of the Act that are listed in Schedule 1 below (“the Orders”); 2. declare the area specifi ed in Schedule 2 to be a restricted area; and 3. declare that the classes of animals, animal products, fodder, fi ttings or vehicles to which this order applies are those described in Schedule 3. SCHEDULE 1 Title of Order Date of Order Declaration of Restricted Area – Moonbi 27 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Woonooka Road Moonbi 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Anambah 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Muswellbrook 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Aberdeen 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – East Maitland 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Timbumburi 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – McCullys Gap 30 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Bunnan 31 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area - Gloucester 31 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Eagleton 29 August 2007 SCHEDULE 2 The area shown in the map below and within the local government areas administered by the following councils: Cessnock City Council Dungog Shire Council Gloucester Shire Council Great Lakes Council Liverpool Plains Shire Council 6836 SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT 3 September 2007 Maitland City Council Muswellbrook Shire Council Newcastle City Council Port Stephens Council Singleton Shire Council Tamworth City Council Upper Hunter Shire Council NEW SOUTH WALES GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No. -

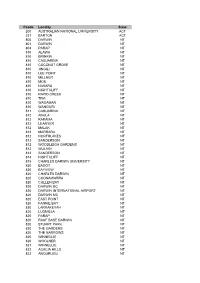

Pcode Locality State 200 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL

Pcode Locality State 200 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY ACT 221 BARTON ACT 800 DARWIN NT 801 DARWIN NT 804 PARAP NT 810 ALAWA NT 810 BRINKIN NT 810 CASUARINA NT 810 COCONUT GROVE NT 810 JINGILI NT 810 LEE POINT NT 810 MILLNER NT 810 MOIL NT 810 NAKARA NT 810 NIGHTCLIFF NT 810 RAPID CREEK NT 810 TIWI NT 810 WAGAMAN NT 810 WANGURI NT 811 CASUARINA NT 812 ANULA NT 812 KARAMA NT 812 LEANYER NT 812 MALAK NT 812 MARRARA NT 812 NORTHLAKES NT 812 SANDERSON NT 812 WOODLEIGH GARDENS NT 812 WULAGI NT 813 SANDERSON NT 814 NIGHTCLIFF NT 815 CHARLES DARWIN UNIVERSITY NT 820 BAGOT NT 820 BAYVIEW NT 820 CHARLES DARWIN NT 820 COONAWARRA NT 820 CULLEN BAY NT 820 DARWIN DC NT 820 DARWIN INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT NT 820 DARWIN MC NT 820 EAST POINT NT 820 FANNIE BAY NT 820 LARRAKEYAH NT 820 LUDMILLA NT 820 PARAP NT 820 RAAF BASE DARWIN NT 820 STUART PARK NT 820 THE GARDENS NT 820 THE NARROWS NT 820 WINNELLIE NT 820 WOOLNER NT 821 WINNELLIE NT 822 ACACIA HILLS NT 822 ANGURUGU NT 822 ANNIE RIVER NT 822 BATHURST ISLAND NT 822 BEES CREEK NT 822 BORDER STORE NT 822 COX PENINSULA NT 822 CROKER ISLAND NT 822 DALY RIVER NT 822 DARWIN MC NT 822 DELISSAVILLE NT 822 FLY CREEK NT 822 GALIWINKU NT 822 GOULBOURN ISLAND NT 822 GUNN POINT NT 822 HAYES CREEK NT 822 LAKE BENNETT NT 822 LAMBELLS LAGOON NT 822 LIVINGSTONE NT 822 MANINGRIDA NT 822 MCMINNS LAGOON NT 822 MIDDLE POINT NT 822 MILIKAPITI NT 822 MILINGIMBI NT 822 MILLWOOD NT 822 MINJILANG NT 822 NGUIU NT 822 OENPELLI NT 822 PALUMPA NT 822 POINT STEPHENS NT 822 PULARUMPI NT 822 RAMINGINING NT 822 SOUTHPORT NT 822 TORTILLA -

Galahs This Is the Longer Version of an Article to Be Published in Australian Historical Studies in April 2010. Copyright Bill

Galahs This is the longer version of an article to be published in Australian Historical Studies in April 2010. Copyright Bill Gammage, 3 November 2008. Email [email protected] When Europeans arrived in Australia, galahs were typically inland birds, quite sparsely distributed. Now they range from coast to coast, and are common. Why did this change occur? Why didn’t it occur earlier? Galahs feed on the ground. They found Australia’s dominant inland grasses too tall to get at the seed, so relied on an agency to shorten them: Aboriginal grain cropping before contact, introduced stock after it. *** On 3 July 1817, near the swamps filtering the Lachlan to the Murrumbidgee and further inland than any white person had been, John Oxley wrote, ‘Several flocks of a new description of pigeon were seen for the first time... A new species of cockatoo or paroquet, being between both, was also seen, with red necks and breasts, and grey backs. I mention these birds particularly, as they are the only ones we have yet seen which at all differ from those known on the east coast’ [1]. Allan Cunningham, Oxley’s botanist, also saw the birds. ‘We shot a brace of pigeons of a new species...’, he noted, ‘Some other strange birds were observed (supposed to be Parrots), about the size and flight of a pigeon, with beautiful red breasts’, and next morning, ‘They are of a light ash colour on the back and wings, and have rich pink breasts and heads’ [1]. In the manner of science parrot and pigeon were shot, and within a few months John Lewin in Sydney drew the first known depictions of them [53]. -

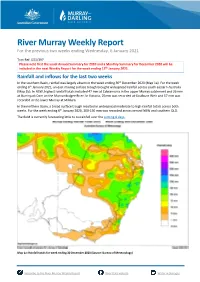

Weekly Report 06 January 2021

River Murray Weekly Report For the previous two weeks ending Wednesday, 6 January 2021 Trim Ref: D21/397 Please note that the usual Annual Summary for 2020 and a Monthly Summary for December 2020 will be included in the next Weekly Report for the week ending 13th January 2021. Rainfall and inflows for the last two weeks In the southern Basin, rainfall was largely absent in the week ending 30th December 2020 (Map 1a). For the week ending 6th January 2021, an east moving surface trough brought widespread rainfall across south eastern Australia (Map 1b). In NSW, highest rainfall totals included 47 mm at Cabramurra in the upper Murray catchment and 26 mm at Burrinjuck Dam on the Murrumbidgee River. In Victoria, 25mm was recorded at Goulburn Weir and 17 mm was recorded in the lower Murray at Mildura. In the northern Basin, a broad surface trough resulted in widespread moderate to high rainfall totals across both weeks. For the week ending 6th January 2020, 100-150 mm was recorded across central NSW and southern QLD. The BoM is currently forecasting little to no rainfall over the coming 8 days. Map 1a: Rainfall totals for week ending 30 December 2020 (Source: Bureau of Meteorology) Subscribe to the River Murray Weekly Report River Data website Water in Storages Map 1b: Rainfall totals for week ending 6 January 2021 (Source: Bureau of Meteorology) The upper Murray tributaries saw a reduction in streamflow during the first week of the Christmas break, however, modest streamflow rises were observed following rainfall in the second week. -

Place Names of South Australia: W

W Some of our names have apparently been given to the places by drunken bushmen andfrom our scrupulosity in interfering with the liberty of the subject, an inflection of no light character has to be borne by those who come after them. SheaoakLog ispassable... as it has an interesting historical association connectedwith it. But what shall we say for Skillogolee Creek? Are we ever to be reminded of thin gruel days at Dotheboy’s Hall or the parish poor house. (Register, 7 October 1861, page 3c) Wabricoola - A property North -East of Black Rock; see pastoral lease no. 1634. Waddikee - A town, 32 km South-West of Kimba, proclaimed on 14 July 1927, took its name from the adjacent well and rock called wadiki where J.C. Darke was killed by Aborigines on 24 October 1844. Waddikee School opened in 1942 and closed in 1945. Aboriginal for ‘wattle’. ( See Darke Peak, Pugatharri & Koongawa, Hundred of) Waddington Bluff - On section 98, Hundred of Waroonee, probably recalls James Waddington, described as an ‘overseer of Waukaringa’. Wadella - A school near Tumby Bay in the Hundred of Hutchison opened on 1 July 1914 by Jessie Ormiston; it closed in 1926. Wadjalawi - A tea tree swamp in the Hundred of Coonarie, west of Point Davenport; an Aboriginal word meaning ‘bull ant water’. Wadmore - G.W. Goyder named Wadmore Hill, near Lyndhurst, after George Wadmore, a survey employee who was born in Plymouth, England, arrived in the John Woodall in 1849 and died at Woodside on 7 August 1918. W.R. Wadmore, Mayor of Campbelltown, was honoured in 1972 when his name was given to Wadmore Park in Maryvale Road, Campbelltown. -

WAIKERIE Afternoon at 2Pm for Guided Tours

Riverland Self Drive History Tour Riverland Self Drive History Tour Celebrating South Australia’s Come on, discover the History Festival Riverland’s vibrant history! THE VILLAGE, HISTORIC LOXTON TREE OF KNOWLEDGE Leave the 21st century behind and View at a glance how severely a high river travel back to when the first can affect this region. By studying the high pioneering families arrived in the river levels on the trunk of this region during the mid-1800s. See magnificent old river red gum, you can how farmers battled heat, drought begin to understand the cycles and impact of the and rabbit plagues and how dry Mallee plains were Murray River system. Lions Park, Grant Schubert Dr, transformed into lush citrus orchards. The everyday Loxton. lives of the early settlers and their families are depicted in over 45 buildings and exhibits in The Village. See how LOXTON’S PEPPER TREEE they lived, where they shopped and banked, and the There are many stories regarding school their children attended. Open Tuesday—Sunday the famous Pepper Tree. Renown 10am to 2pm (Closed Christmas Day and Good Friday) for its connection to William Charles PH: 8584 7194. Allen Hosking Dr, Loxton. Loxton who occupied a hut in close www.thevillageloxton.com.au proximity to where the Pepper Tree stands. Located on the exterior boundary of The THE 1956 MURRAY RIVER FLOOD EXHIBITION Village, Loxton. Allen Hosking Drive, Loxton. Located within The Village, Loxton. View the amazing collection of photographs from all over the Riverland KINGSTON BRIDGE LOOKOUT showing the destruction and heart break left as the One of Australia’s greatest waters of the River Murray rose by a mammoth height explorers, Captain Charles Sturt in between May 1956 and January 1957. -

Weekly Report 28 April 2021

River Murray Weekly Report For the week ending Wednesday, 28 April 2021 Trim Ref: D21/10590 Rainfall and inflows Little to no rainfall was observed across the Murray Darling Basin this week (Map 1). Specific information about flows at key locations can be found at the MDBA’s River Murray data webpage. The Bureau of Meteorology is currently forecasting widespread rainfall across much of the Basin in the coming week. Following heavy rain in late March, Water NSW now estimate that 800-950 GL of inflow may reach Menindee Lakes as a result of flow in the Darling River. This estimate may be revised further in coming weeks as flows move towards Menindee Lakes. These inflows are expected to result in the water stored in Menindee Lakes increasing above the trigger volume (640 GL), which means the Menindee Lakes will be part of the River Murray shared water resources. For updates on flow forecasting in the northern Basin please see the Water NSW website. Up-to-date river data for sites in the upper Murray can also be found on BoM’s website and in the Murray River Basin Daily River Report at the Water NSW website. Map 1: Murray-Darling Basin rainfall for the week ending 28 April 2021. Source: Bureau of Meteorology. Subscribe to the River Murray Weekly Report River Data website Water in Storages River Murray Weekly Report River operations • Significant flows in the northern Basin are contributing to increased storage at Menindee Lakes. • Water for the environment pulse taking place in the Goulburn River and Murrumbidgee River • River users and houseboat owners should be aware that river levels will continue to vary over the coming week. -

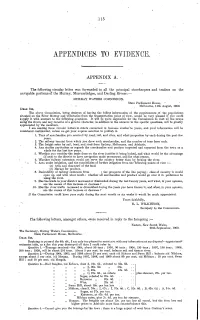

Appendices to Evidence

115 APPENDICES TO EVIDENCE. APPENDIX A. The following circular letter was forwarded to all the principal storekeepers and traders on the navigable portions of the Murray, Murrumbidgee, and Darlillg Rivers MURRAY WATERS COMMISSION. State Parliament House, Melbourne, 11th August, 1909. DEAN Sm, The above Commission, being desirous of having the fullest information of the requirements of the pO})ltlatiollS situated on the River :Murray and tributaries hom the transportation point of view, would be very pleased if you cOllld supply it with answers to the following questions. It will be quite impossible for the Commission to, visit nil the towns along the rivers, and any remarks of a general character, in add~tion to the answers to the specific questions, will be greatly appreciated by the members. I am sending these circular letters to others concerned in business similar 'to yonrs, and your information will be consideJ:ed confidential, unless we get your express sanction to publish it. 1. Tons of merchandise you received by road, rail, and river, and what propo~tioll by each during the past few years. 2. The railway termini hom which you drew such merchandise, and the number of tons from' each. 3. The freight rates by rail, boat, and road, hom Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide. 4. Any similar particul!l,rs as regards the merchandise and produce imported and exported from the town as a whole for the last few years. ' 5. Whether ,you consider the trade done on the river justifies it being locked, and what would be the advantage (if any) to the district to have navigation made permanent, and for what reason. -

Aboriginal History Journal: Volume 21

Aboriginal History Volume twenty-one 1997 Aboriginal History Incorporated The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Secretary), Peter Grimshaw (Treasurer/Public Officer), Neil Andrews, Richard Baker, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Luise Hercus, Bill Humes, Ian Keen, David Johnston, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Diane Smith, Elspeth Young. Correspondents Jeremy Beckett, Valerie Chapman, Ian Clark, Eve Fesl, Fay Gale, Ronald Lampert, Campbell Macknight, Ewan Morris, John Mulvaney, Andrew Markus, Bob Reece, Henry Reynolds, Shirley Roser, Lyndall Ryan, Bruce Shaw, Tom Stannage, Robert Tonkinson, James Urry. Aboriginal History aims to present articles and information in the field of Australian ethnohistory, particularly in the post-contact history of the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia will be welcomed. Issues include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, resumes of current events, archival and bibliographical articles, and book reviews. Editors 1997 Rob Paton and Di Smith, Editors, Luise Hercus, Review Editor and Ian Howie Willis, Managing Editor. Aboriginal History Monograph Series Published occasionally, the monographs present longer discussions or a series of articles on single subjects of contemporary interest. Previous monograph titles are D. Barwick, M. Mace and T. Stannage (eds), Handbook of Aboriginal and Islander History; Diane Bell and Pam Ditton, Law: the old the nexo; Peter Sutton, Country: Aboriginal boundaries and land ownership in Australia; Link-Up (NSW) and Tikka Wilson, In the Best Interest of the Child? Stolen children: Aboriginal pain/white shame, Jane Simpson and Luise Hercus, History in Portraits: biographies of nineteenth century South Australian Aboriginal people.