Introduction to Instalment 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PMMS L'homme Arme' Masses Discography

Missa L’homme armé Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber This discography of almost forty Masses composed on the cantus firmus of L’homme armé (twenty- eight of them currently represented) makes accessible a list of this group of recordings not easily found in one place. A preliminary list was published in Fanfare 26:4 (March/April 2003) in conjunction with a recording of Busnoys’s Mass. The composers are listed in the order found in Craig Wright, The Maze and the Warrior (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2001), p. 288; the list is alphabetical within broad eras. In particular, he discusses Du Fay (pp. 175ff.), Regis (pp. 178ff.), the Naples Masses (pp. 184ff.), and Josquin des Prez (pp. 188ff.). Richard Taruskin, “Antoine Busnoys and the L’Homme armé Tradition,” Journal of AMS, XXXIX:2 (Summer 1986), pp. 255-93, writes about Busnoys and the Naples Masses, suggesting (pp. 260ff.) that Busnoys’s Mass is the earliest of the group and that the Naples Masses are also by him. Fabrice Fitch, Johannes Ockeghem: Masses and Models (Paris, 1997, pp. 62ff.), suggests that Ockeghem’s setting is the earliest. Craig Wright, op. cit. (p. 175), calls Du Fay’s the first setting. Alejandro Planchart, Guillaume Du Fay (Cambridge, 2018, p. 594) firmly calls Du Fay and Ockeghem the composers of the first two Masses, jointly commissioned by Philip the Good in May 1461. For a discussion of Taruskin’s article, see Journal of AMS, XL:1 (Spring 1987), pp. 139-53 and XL:3 (Fall 1987), pp. 576-80. See also Leeman Perkins, “The L’Homme armé Masses of Busnoys and Okeghem: A Comparison,” Journal of Musicology, 3 (1984), pp. -

Notes on Heinrich Isaac's Virgo Prudentissima Author(S): Alejandro Enrique Planchart Source: the Journal of Musicology, Vol

Notes on Heinrich Isaac's Virgo prudentissima Author(s): Alejandro Enrique Planchart Source: The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Winter 2011), pp. 81-117 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jm.2011.28.1.81 Accessed: 26-06-2017 18:47 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Musicology This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Mon, 26 Jun 2017 18:47:45 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Notes on Heinrich Isaac’s Virgo prudentissima ALEJandro ENRIQUE PLANCHART Thomas Binkley in memoriam In 1520 Sigmund Grimm and Marx Wirsung published their Liber selectarum cantionum quas vulgo mutetas appellant, a choirbook that combined double impression printing in the manner of Petrucci with decorative woodcuts. As noted in the dedicatory letter by the printers and the epilogue by the humanist Conrad Peutinger, the music was selected and edited by Ludwig Senfl, who had succeeded his teacher, Heinrich Isaac, as head of Emperor Maximilian’s chapel 81 until the emperor’s death in 1519. -

Reception of Josquin's Missa Pange

THE BODY OF CHRIST DIVIDED: RECEPTION OF JOSQUIN’S MISSA PANGE LINGUA IN REFORMATION GERMANY by ALANNA VICTORIA ROPCHOCK Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Alanna Ropchock candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree*. Committee Chair: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Committee Member: Dr. L. Peter Bennett Committee Member: Dr. Susan McClary Committee Member: Dr. Catherine Scallen Date of Defense: March 6, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ........................................................................................................... i List of Figures .......................................................................................................... ii Primary Sources and Library Sigla ........................................................................... iii Other Abbreviations .................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... v Abstract ..................................................................................................................... vii Introduction: A Catholic -

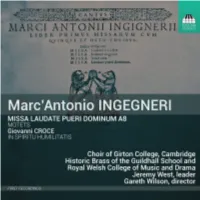

TOCC0556DIGIBKLT.Pdf

THE COUNCIL OF TRENT AND THE MUSIC OF MARC’ANTONIO INGEGNERI by Giampiero Innocente The Protestant Reformation was a storm which shook the Catholic church in every way: its dogmas, its hierarchies and the certainties of faith on which it had been based for 1,500 years were undermined at their very foundations. Luther and the reformers had called into question not only its theology and how it was articulated but also the nature of its community, its liturgy, its rituals and the music associated with them. A direct precursor of those musical changes was Luther’s translation of the Bible from Latin to German, completed in 1534, a work that became a true monument of the German language and a document that helped establish a ‘national’ identity. Although Luther had not totally rejected every musical form of the Catholic tradition – he preserved Latin hymns, for example – the new style of liturgical music he promoted was designed for a congregation that was no longer Catholic: the predominance of the Word of God, the abandonment of faith in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and communion understood as being taken only ‘in memory’ of Christ’s Last Supper were fundamental elements that emboldened the newly reformed Protestant worship and generated new musical forms which were peculiar, and central, to it. Faced with this turn of events, the Catholic church gathered itself in order to launch a powerful ‘counter-reformation’ of its own, and between 1545 and 1563 its senior cardinals and clergy were convened to meet over a series of 25 sessions, now known as the Council of Trent, in order to respond to the attacks of the Protestant world that were spreading rapidly in northern Europe. -

Missa Sine Nomine

Guillaume Du Fay Opera Omnia 03/01 Missa sine nomine Edited by Alejandro Enrique Planchart Marisol Press Santa Barbara, 2008 Guillaume Du Fay Opera Omnia Edited by Alejandro Enrique Planchart 01 Cantilena, Paraphrase, and New Style Motets 02 Isorhythmic and Mensuration Motets 03 Ordinary and Plenary Mass Cycles 04 Proper Mass Cycles 05 Ordinary of the Mass Movements 06 Proses 07 Hymns 08 Magnificats 09 Benedicamus domino 10 Songs 11 Plainsongs 12 Dubious Works and Works with Spurious Attributions © Copyright 2008 by Alejandro Enrique Planchart, all rights reserved. Guillaume Du Fay, Missa sine nomine: 1 03/01 Missa sine nomine Kyrie eleison = Guillaume Du Fay Cantus Ky ri e e [ ] Contratenor 8 Ky ri e e [ ] Tenor 8 Ky ri e e 6 lei son. Ky ri e e 8 lei son. Ky ri e e 8 lei son. Ky ri e e 12 lei son. Ky ri e e 8 lei son. Ky ri e 8 lei son. Ky ri e 18 lei son, e lei son. 8 e lei son, e lei son. 8 e lei lei son, e lei son. 24 Chri ste e [ ] 8 Chri ste e [ ] 8 Chri ste e D-OO Guillaume Du Fay, Missa sine nomine: 2 29 lei son. Chri 8 lei son. Chri 8 lei son. Chri 34 ste e lei son. Chri 8 ste e lei son. Chri 8 ste e lei son. Chri 40 ste e lei son. 8 ste e lei son. 8 ste e lei son. 46 Ky ri e e 8 Ky ri e e 8 Ky ri e e 50 8 8 D-OO Guillaume Du Fay, Missa sine nomine: 3 54 lei son. -

Mahrt, William

CURRICULUM VITÆ William Peter Mahrt Associate Professor, Department of Music, Stanford University EDUCATION Gonzaga University, 1957–60; University of Washington, 1960–63; B.A., 1961, M.A., 1963; Stanford Univ., 1963–69; Ph.D., 1969 POSITIONS Case Western Reserve University, Visiting Assistant Professor, 1969–71 Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester, Assistant Professor, 1971–72 Stanford University, Acting Asst. Prof., 1972–74, Asst. Prof., 1974–80, Assoc. Prof., 1980–present. MEMBERSHIPS American Musicological Society, Church Music Association of America, Consociatio Internationalis Musicae Sacrae, Dante Society of America, International Machaut Society, Latin Liturgy Association, Medieval Academy of America, Medieval Association of the Pacific, Plainsong and Medieval Music Society, Dutch Musicological Society. OFFICES Examining Committee for Advanced Placement in Music, College Board, 1972–80; President, Renaissance Conference of Northern California, 1980–81; Advisory Board, National Endowment for the Humanities, documentary on Sumatran music, 1983–85; Chairman, Stanford University Subcommittee on Distribution Requirements, 1983–84; Chairman, Stanford Western Culture Program, 1984–85; President, Northern California Chapter, American Musicological Society, 1987–1991; Acting Chairman, Department of Music, Stanford University, Spring-Summer 1989; Chairman, Bay Area Chapter, Latin Liturgy Association, 1991– present. Performance Committee for the Annual Meeting of the American Musicological Society, 2005–2008. Haskins Medal Committee of the Medieval Academy of America, 2005–2008. President, Church Music Association of America, 2005–present. Editor, Sacred Music, 2006–present. Board of Directors, Friends of Music, Stanford University, 2000–present. Board of Directors, Associates of Stanford University Libraries, 2004–2007. FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS National Endowment for the Humanities-Newberry Library Fellowship, 1976; Stanford-Mellon Junior Faculty Fellowship, 1978–79; Stanford University Summer Fellowship, 1982–85; Albert Schweitzer Medal, St. -

8010 Missa Sine Nomine-Ockeghem

(LEMS 8010) THE TWO THREE-VOICE MASSES JOHANNES OCKEGHEM (ca. 1410 - 1497) MISSA SINE NOMINE MISSA QUINTI TONI Music of the Middle Ages Performed by SCHOLA DISCANTUS Kevin Moll, Director THE WORKS It is now generally agreed that Johannes Ockeghem was one of the two foremost composers of the 15th century - the other being Guillaume Dufay (ca. 1400 - 1474). Both men figure prominently in the early history of the cyclic Mass Ordinary, i.e., the musical unification of disparate polyphonic settings of those items in the Catholic mass liturgy whose texts do not change from day to day. These Ordinary sections are distinct from other parts of the mass whose texts are "Proper" to one specific day. It is clear from comments of contemporary chroniclers, such as the important musical theorist Johannes Tinctoris, that the polyphonic Mass Ordinary was considered the most important and prestigious category of composition in the years after about 1450, and it is precisely this genre of sacred music, which is represented on this disc. 1 ORDINARY PROPER Introit Kyrie Gloria Gradual Alleluia + Sequence Credo Offertory Sanctus Agnus Communion (Ite missa est) The items of the Ordinary occur at widely scattered places in the liturgy of the Catholic mass, as can be seen from the list above. (The list contains only those portions of the liturgy which are properly sung, as opposed to being spoken or intoned by the priest.) The Ite missa est, or dismissal formula, was occasionally set to polyphony in the 14th century, but almost never in the 15th. I should also be mentioned that in the Gloria and Credo sections of the mass, the first words were always intoned by the priest, hence the polyphony begins with the words "Et ine terra" and "Patrem omnipotentem", respectively. -

Early Music Segment Catalogue

Early Music Mysticism to Majesty - the era of Early Music While the chronology of early music may resist an exact defi nition, the advancement of European musical styles portrayed in this catalogue takes us on a fascinating journey from the emergence of gregorian chant (c.750) up to the development of early Baroque music (c.1600). Vocal, instrumental, sacred and secular works are gathered either in discrete discs of the more celebrated composers from the Mediaeval and Renaissance periods, such as Leonin, Perotin, Byrd and Monteverdi, or appear in themed compilations: French chansons, German lute songs, Italian dramatic laments, for example. Life during those distant eras is brought vividly to life through the music. The exuberant and bawdy 11th- and 12th-century texts of Carmina Burana, spread by itinerant scholars and clerics, remind us how Latin was a pan-european language that superseded those of individual nations. The madrigals of Carlo Gesualdo, the calculating murderer of his wife and her lover, play out against the untouchable status that a Venetian nobleman then enjoyed. With the absence of lighting and sets, the dramatic importance of music in Shakespeare’s plays is underscored by the musical subtleties created for his texts by composers contemporary with the bard. The artistic interest shown by influential rulers is reflected not only in the sound of the compositions, but also in the splendour of their presentation. The works of Desprez, de la Rue and Willaert were as beautiful to look at through the glorious calligraphy of the A-La-mi-Re manuscripts as they were to listen to. -

Critical Commentary to Nos 15-21

627 CRITICAL COMMENTARY TO NOS 15-21 15. Missa Le serviteur II Kyrie (Trent 89 ff. 153v-154r, unicum, DTȌ VII inventory no. 606). [Superius]; 84: this note and the double custos are given on a short end-of-stave extension. Contra; 13,2 & 44: ns / 72: b ind before 72,1. Tenor; 1, 13,3 & 24: ns / 73,1-2: the middle of this void lig is colored for no apparent reason / 75,4: ns / 78: 3 & 4 are sm sm. Underlay; ‘Kyrie’ and ‘Xpe’ are given at the start of each section, plus ‘eleyson’ at the end of each section. However, the presence of repeated notes at the same pitch (Tenor, 4-5, Superius 13, Tenor 30-31 & Superius 68-69) argue that at least threefold ‘Kyrie/Christe eleyson’ is needed in each section, plus extra repeats of some words. Accordingly, my texting sometimes uses the four-syllable ‘eleÿson’ and has multiple repeats in Kyrie I, at 30-37, at 68-72 and at the closing measures of Kyrie II. For those who do not like the note-splitting in this edition, I offer the following alternative which removes some of the split values. 1. At Tenor 1-2 sing the notes unsplit to ‘Kyrie e-‘ with the ‘e’ elided. 2. At Tenor 13, move ‘Kyri-‘ to the last two notes in the measure; in the Contra above omit the editorial ‘Kyrie’ and sing 13,3 to ‘e-‘. 3. At Tenor 24-25 sing the text elided instead of splitting the note. Bibliography; Gottlieb, op. cit., no. 10, Mitchell, The Paleography and Repertory…, I, pp. -

An Experiment in Musical Unity, Or: the Sheer Joy of Sound

An experiment in musical unity, or: The sheer joy of sound. The anonymous Sine nomine mass in MS Cappella Sistina 14 Christoffersen, Peter Woetmann Published in: Danish Yearbook of Musicology Publication date: 2019 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Christoffersen, P. W. (2019). An experiment in musical unity, or: The sheer joy of sound. The anonymous Sine nomine mass in MS Cappella Sistina 14. Danish Yearbook of Musicology, 42, 54–78. http://www.dym.dk/dym_pdf_files/volume_42/dym42_1_03.pdf Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 Danish Yearbook of Musicology 42 • 2018 © 2018 by the authors Danish Yearbook of Musicology · Volume 42 · 2018 Dansk Årbog for Musikforskning Editors Michael Fjeldsøe · [email protected] Peter Hauge · [email protected] Editorial Board Lars Ole Bonde, University of Aalborg; Peter Woetmann Christoffersen, University of Copenhagen; Bengt Edlund, Lund University; Daniel M. Grimley, University of Oxford; Lars Lilliestam, Göteborg University; Morten Michelsen, University of Copenhagen; Steen Kaargaard Nielsen, University of Aarhus; Siegfried Oechsle, Christian-Albrechts- Universität, Kiel; Nils Holger Petersen, University of Copenhagen; Søren Møller Sørensen, University of Copenhagen Production Hans Mathiasen Address c/o Department of Arts and Cultural Studies, Section of Musicology, University of Copenhagen, Karen Blixens Vej 1, DK-2300 København S Each volume of Danish Yearbook of Musicology is published continously in sections: 1 · Articles 2 · Reviews 3 · Bibliography 4 · Reports · Editorial ISBN 978-87-88328-33-2 (volume 42); ISSN 2245-4969 (online edition) Danish Yearbook of Musicology is a peer-reviewed journal published by the Danish Musicological Society on http://www.dym.dk/ An experiment in musical unity, or: The sheer joy of sound. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 74-3256

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Some Notes on the Reception of Josquin and of Northern Idioms in Portuguese Music and Culture*

Some Notes on the Reception of Josquin and of Northern Idioms in Portuguese Music and Culture* João Pedro d’Alvarenga From Robert Stevenson’s contribution to the 1971 Josquin Festival-Conference we learn that the majority of the surviving evidence concerning Josquin’s impact in the Iberian Peninsula and particularly in Portugal dates from the late 1530s and 1540s onwards.1 By then, thanks to his reputation, Josquin had become a symbol in Portuguese humanistic culture and, as Kenneth Kreitner puts it in a recent article, he had turned into ‘a kind of obsession’ for Spanish musicians and patrons.2 Yet (again in Kreitner’s words) ‘during his own lifetime, if the extant sources are any indication, Josquin seems to have been regarded in Spain as just one composer among many’.3 The main surviving collection of Portuguese sources of polyphony dating from the first half of the sixteenth century consists of just five manuscript volumes, all originating from the Augustinian monastery of Santa Cruz in Coimbra (Coimbra, Biblioteca Geral da Universidade MM 6, MM 7, MM 9, MM 12, and MM 32).4 The manuscripts transmit Spanish, northern, and local repertories. According to Owen Rees, they were all compiled from around 1540 to the mid-1550s. Most of the pieces in Coimbra MM 12, apparently the oldest member of the group, can be related to the Spanish court. Coimbra MM 6 includes no northern composers.5 Other important, coeval Portuguese extant sources of different provenance are: – Ms. CIC 60 in the National Library of Portugal [Lisbon CIC 60]: a small songbook of unknown origin containing both sacred and secular Iberian repertories.