Some General Observations on Mass Composition in the Renaissance Charles Lathan Hill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(1) Western Culture Has Roots in Ancient and ___

5 16. (50) If a 14th-century composer wrote a mass. what would be the names of the movement? TQ: Why? Chapter 3 Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Agnus Dei. The text remains Roman Liturgy and Chant the same for each day throughout the year. 1. (47) Define church calendar. 17. (51) What is the collective title of the eight church Cycle of events, saints for the entire year services different than the Mass? Offices [Hours or Canonical Hours or Divine Offices] 2. TQ: What is the beginning of the church year? Advent (four Sundays before Christmas) 18. Name them in order and their approximate time. (See [Lent begins on Ash Wednesday, 46 days before Easter] Figure 3.3) Matins, before sunrise; Lauds, sunrise; Prime, 6 am; Terce, 9 3. Most important in the Roman church is the ______. am; Sext, noon; Nones, 3 pm; Vespers, sunset; Mass Compline, after Vespers 4. TQ: What does Roman church mean? 19. TQ: What do you suppose the function of an antiphon is? Catholic Church To frame the psalm 5. How often is it performed? 20. What is the proper term for a biblical reading? What is a Daily responsory? Lesson; musical response to a Biblical reading 6. (48) Music in Context. When would a Gloria be omitted? Advent, Lent, [Requiem] 21. What is a canticle? Poetic passage from Bible other than the Psalms 7. Latin is the language of the Church. The Kyrie is _____. Greek 22. How long does it take to cycle through the 150 Psalms in the Offices? 8. When would a Tract be performed? Less than a week Lent 23. -

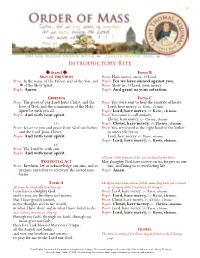

Stand Priest: in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy

1 Stand Form B SIGN OF THE CROSS Priest: Have mercy on us, O Lord. Priest: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and People: For we have sinned against you. ✠of the Holy Spirit. Priest: Show us, O Lord, your mercy. People: Amen. People: And grant us your salvation. GREETING Form C Priest: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the Priest: You were sent to heal the contrite of heart: love of God, and the communion of the Holy Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Spirit be with you all. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: And with your spirit. Priest: You came to call sinners: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Or: People: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Priest: Grace to you and peace from God our Father Priest: You are seated at the right hand of the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. to intercede for us: People: And with your spirit. Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Or: Priest: The Lord be with you. People: And with your spirit. All forms of the Penitential Act are concluded by the Priest: PENITENTIAL ACT May almighty God have mercy on us, forgive us our Priest: Brethren, let us acknowledge our sins, and so sins, and bring us to everlasting life. prepare ourselves to celebrate the sacred mys- People: Amen. teries. Form A The Kyrie eleison invocations follow, unless they have just occurred All pause for silent reflection then say: in a formula of the Penitential Act (Form C). -

Heinrich Isaac's

'i~;,~\,;:( ::' Heinrich Isaac's, :,t:1:450-1517) Choralis Constantinus::! C¢q is an anthology of 372; polyphonic Neglected Treasure - motets, setting the textsolthe Prop er of the Mass, accompanied by five Heinrich Isaac's polyphonic settings dflheOrdinary. A larger and more complete suc Choralis Constantinus cessor to the Magnus,iij:Jer organi of Leonin, the CC was fir~t 'pulJlished in three separate volum~s)' by the Nuremberg publisher j'lieronymous by James D. Feiszli Formschneider, beginning in 1550 and finishing in 1555'>:B.egarded by musicologists as a : ,',fsumma of Isaac's reputation prior to his move to assist him in finishing some in Netherlandish polyphony about to Florence.3 complete work. Isaac was back in 1500, a comprehepsive com In Florence, Isaac was listed on Florence by 1515 and remained the rosters of a number of musical there until his death in 1517. pendium of virtually :fi:llli devices, manners, and styles prevalent at the organizations supported by the Isaac was a prolific and versatile time"! the CC today'i~,v:irtually ig Medici, in addition to serving as composer. He wrote compositions in nored by publishers:'Cing, hence, household tutor to the Medici fami all emerging national styles, produc choral ensembles. Few!or.:the com ly. He evidently soon felt comfort ing French chansons, Italian frottoie, positions from this i,'cblI'ection of able enough in Italy to establish a and German Lieder. That he, a Renaissance polyphonyiihave ever permanent residence in Florence secular musician who held no been published in chqrat!octavo for and marry a native Florentine. -

APPENDIX 1 Inventories of Sources of English Solo Lute Music

408/2 APPENDIX 1 Inventories of sources of English solo lute music Editorial Policy................................................................279 408/2.............................................................................282 2764(2) ..........................................................................290 4900..............................................................................294 6402..............................................................................296 31392 ............................................................................298 41498 ............................................................................305 60577 ............................................................................306 Andrea............................................................................308 Ballet.............................................................................310 Barley 1596.....................................................................318 Board .............................................................................321 Brogyntyn.......................................................................337 Cosens...........................................................................342 Dallis.............................................................................349 Danyel 1606....................................................................364 Dd.2.11..........................................................................365 Dd.3.18..........................................................................385 -

The Agnus Dei

New and Corrected Translation of the Mass – Part 26 The Agnus Dei Lamb of God, Gen 22.8; Ex 12; 1 Cor 5.7 you take away the sins of the world, Lev 16.21; Jn 1.29 have mercy on us. Lamb of God, 1 Pet 1.19; Rev 5.6 you take away the sins of the world, 1 Jn 2.2 have mercy on us Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world, grant us peace. John 14.27; 20.26 Immediately after the Pax, the priest begins the Fraction, i.e. breaking the Host, which shows the death of Jesus, whose body was broken for us in the Sacrifice of the Cross (although not one of His bones was broken, cf. John 19.36). The priest takes a small particle of the Host and adds it to the Precious Blood in the chalice. This act, called the ‘commingling’, signifies the Resurrection, the coming together again of Christ’s Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity (even in death His Divinity remained united to all three preceding, which are part of His humanity). The Agnus Dei is a chant which accompanies the Fraction. Everyone says or sings it, using the words of St John the Baptist to point out Jesus as the Messiah. In the Eastern churches the sacrificial gifts are called “the Lamb”. It is the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist that moves us to call Jesus ‘Lamb of God’ at this point of the Mass, cf. “I saw a Lamb standing, as it were slain” (Rev 5.6). -

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there. -

SACRED MUSIC Volume 99, Number 1, Spring 1972 Cistercian Gradual (12Th Century, Paris, Bibl

SACRED MUSIC Volume 99, Number 1, Spring 1972 Cistercian Gradual (12th century, Paris, Bibl. Nat., ms . lat. 17,328) SACRED MUSIC Volume 99, Number 1 , Spring 1972 BERNSTEIN'S MASS 3 Herman Berlinski TU FELIX AUSTRIA 9 Reverend Robert Skeris MUSICAL SUPPLEMENT 13 REVIEWS 20 FROM THE EDITOR 25 NEWS 26 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caeci/ia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of publication: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minne sota 55103. Editorial office: Route 2, Box I, Irving, Texas 75062. Editorial Board Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O.Cist., Editor Mother C. A. Carroll, R.S.C.J. Rev. Lawrence Heiman, C.PP.S. J. Vincent Higginson Rev. Peter D. Nugent Rev. Elmer F. Pfeil Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler Frank D. Szynskie Editorial correspondence: Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O.Cist., Route 2, Box I, Irving, Texas 75062 News: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler, 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 Music for Review: Mother C. A. Carroll, R.S.C.J., Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart, Purchase, New York 10577 Rev. Elmer F. Pfeil 3257 South Lake Drive Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53207 Membership and Circulation: Frank D. Szynskie, Boys Town, Nebraska 68010 AdvertisinR: Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O.Cist. CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Dr. Roger Wagner Vice-president Noel Goemanne General Secretary Rev. Robert A. Skeris Treasurer Frank D. Szynskie Directors Robert I. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

The Credo the Rt

The Diocese of the Mid-Atlantic States Of the Anglican Catholic Church The credo The Rt. Rev’d D. Francis Lerow, Managing Editor The Rev’d Fr. T.L. Crowder, Content Editor Saint Aidan, Bishop and Confessor 31 August, A.D. 2015 The Crozier The Right Rev’d D. Francis Lerow, Bishop Ordinary Missions and Decisions, Planning and Money For many of our parishes, renewal tends to be an ongoing affair. We think very hard about our home parish. All of us want our church to have impact on the community and our community to have greater access to worship and the Traditional Anglican way. We depend on our vestries to drive the wagon that ensures that proper planning and resources are available to support the annual plan established at the Annual Parish Meetings. The problem with planning is that it quickly can lose the interest of the members of the parish. It is easy to fall back into our old ways, thinking that the Sunday Worship Service is all we need to bring them to Christ and eventually membership in the Church. Or if we have a young electrifying priest that will lead the way all will be well. It would be nice if it was that easy. But, we all know it is not. So what does it take? What kind of investment of time and resources does it take to really make things happen? What will cause the kind of renewal for which we all hope and pray? The business metric used to determine the effort and cost to sell a particular item of merchandise, as a rule of thumb, is to measure how many times their product gets the attention of a potential buyer. -

Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 As a Stylistic Guide

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2008 Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide Jonathan Candler Kilgore University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Composition Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Kilgore, Jonathan Candler, "Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide" (2008). Dissertations. 1129. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC GUIDE by Jonathan Candler Kilgore A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts August 2008 COPYRIGHT BY JONATHAN CANDLER KILGORE 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC -

The Anthems of Thomas Ford (Ca. 1580-1648). Fang-Lan Lin Hsieh Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1989 The Anthems of Thomas Ford (Ca. 1580-1648). Fang-lan Lin Hsieh Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Hsieh, Fang-lan Lin, "The Anthems of Thomas Ford (Ca. 1580-1648)." (1989). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4722. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4722 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N.