An Experiment in Musical Unity, Or: the Sheer Joy of Sound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For OCKEGHEM

ss CORO hilliard live CORO hilliard live 2 Producer: Antony Pitts Recording: Susan Thomas Editors: Susan Thomas and Marvin Ware Post-production: Chris Ekers and Dave Hunt New re-mastering: Raphael Mouterde (Floating Earth) Translations of Busnois, Compère and Lupi by Selene Mills Cover image: from an intitial to The Nun's Priest's Tale (reversed) by Eric Gill, with thanks to the Goldmark Gallery, Uppingham: www.goldmarkart.com Design: Andrew Giles The Hilliard Ensemble David James countertenor Recorded by BBC Radio 3 in St Jude-on-the-Hill, Rogers Covey-Crump tenor Hampstead Garden Suburb and first broadcast on John Potter tenor 5 February 1997, the eve of the 500th anniversary Gordon Jones baritone of the death of Johannes Ockeghem. Previously released as Hilliard Live HL 1002 Bob Peck reader For Also available on coro: hilliard live 1 PÉROTIN and the ARS ANTIQUA cor16046 OCKEGHEM 2007 The Sixteen Productions Ltd © 2007 The Sixteen Productions Ltd N the hilliard ensemble To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs, visit www.thesixteen.com cor16048 The hilliard live series of recordings came about for various reasons. 1 Kyrie and Gloria (Missa Mi mi) Ockeghem 7:10 At the time self-published recordings were a fairly new and increasingly 2 Cruel death.... Crétin 2:34 common phenomenon in popular music and we were keen to see if 3 In hydraulis Busnois 7:50 we could make the process work for us in the context of a series of public concerts. Perhaps the most important motive for this experiment 4 After this sweet harmony... -

PMMS L'homme Arme' Masses Discography

Missa L’homme armé Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber This discography of almost forty Masses composed on the cantus firmus of L’homme armé (twenty- eight of them currently represented) makes accessible a list of this group of recordings not easily found in one place. A preliminary list was published in Fanfare 26:4 (March/April 2003) in conjunction with a recording of Busnoys’s Mass. The composers are listed in the order found in Craig Wright, The Maze and the Warrior (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2001), p. 288; the list is alphabetical within broad eras. In particular, he discusses Du Fay (pp. 175ff.), Regis (pp. 178ff.), the Naples Masses (pp. 184ff.), and Josquin des Prez (pp. 188ff.). Richard Taruskin, “Antoine Busnoys and the L’Homme armé Tradition,” Journal of AMS, XXXIX:2 (Summer 1986), pp. 255-93, writes about Busnoys and the Naples Masses, suggesting (pp. 260ff.) that Busnoys’s Mass is the earliest of the group and that the Naples Masses are also by him. Fabrice Fitch, Johannes Ockeghem: Masses and Models (Paris, 1997, pp. 62ff.), suggests that Ockeghem’s setting is the earliest. Craig Wright, op. cit. (p. 175), calls Du Fay’s the first setting. Alejandro Planchart, Guillaume Du Fay (Cambridge, 2018, p. 594) firmly calls Du Fay and Ockeghem the composers of the first two Masses, jointly commissioned by Philip the Good in May 1461. For a discussion of Taruskin’s article, see Journal of AMS, XL:1 (Spring 1987), pp. 139-53 and XL:3 (Fall 1987), pp. 576-80. See also Leeman Perkins, “The L’Homme armé Masses of Busnoys and Okeghem: A Comparison,” Journal of Musicology, 3 (1984), pp. -

The Tallis Scholars

Friday, April 10, 2015, 8pm First Congregational Church The Tallis Scholars Peter Phillips, director Soprano Alto Tenor Amy Haworth Caroline Trevor Christopher Watson Emma Walshe Clare Wilkinson Simon Wall Emily Atkinson Bass Ruth Provost Tim Scott Whiteley Rob Macdonald PROGRAM Josquin Des Prez (ca. 1450/1455–1521) Gaude virgo Josquin Missa Pange lingua Kyrie Gloria Credo Santus Benedictus Agnus Dei INTERMISSION William Byrd (ca. 1543–1623) Cunctis diebus Nico Muhly (b. 1981) Recordare, domine (2013) Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) Tribute to Caesar (1997) Byrd Diliges dominum Byrd Tribue, domine Cal Performances’ 2014–2015 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 26 CAL PERFORMANCES PROGRAM NOTES he end of all our exploring will be Josquin, who built on the cantus firmus tradi- Tto arrive where we started and know the tion of the 15th century, developing the freer place for the first time.” So writes T. S. Eliot in parody and paraphrase mass techniques. A cel- his Four Quartets, and so it is with tonight’s ebrated example of the latter, the Missa Pange concert. A program of cycles and circles, of Lingua treats its plainsong hymn with great revisions and reinventions, this evening’s flexibility, often quoting more directly from performance finds history repeating in works it at the start of a movement—as we see here from the Renaissance and the present day. in opening soprano line of the Gloria—before Setting the music of William Byrd against moving into much more loosely developmen- Nico Muhly, the expressive beauty of Josquin tal counterpoint. Also of note is the equality of against the ascetic restraint of Arvo Pärt, the imitative (often canonic) vocal lines, and exposes the common musical fabric of two the textural variety Josquin creates with so few ages, exploring the long shadow cast by the voices, only rarely bringing all four together. -

Renaissance Terms

Renaissance Terms Cantus firmus: ("Fixed song") The process of using a pre-existing tune as the structural basis for a new polyphonic composition. Choralis Constantinus: A collection of over 350 polyphonic motets (using Gregorian chant as the cantus firmus) written by the German composer Heinrich Isaac and his pupil Ludwig Senfl. Contenance angloise: ("The English sound") A term for the style or quality of music that writers on the continent associated with the works of John Dunstable (mostly triadic harmony, which sounded quite different than late Medieval music). Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Fauxbourdon: A musical texture prevalent in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, produced by three voices in mostly parallel motion first-inversion triads. Only two of the three voices were notated (the chant/cantus firmus, and a voice a sixth below); the third voice was "realized" by a singer a 4th below the chant. Glogauer Liederbuch: This German part-book from the 1470s is a collection of 3-part instrumental arrangements of popular French songs (chanson). Homophonic: A polyphonic musical texture in which all the voices move together in note-for-note chordal fashion, and when there is a text it is rendered at the same time in all voices. Imitation: A polyphonic musical texture in which a melodic idea is freely or strictly echoed by successive voices. A section of freer echoing in this manner if often referred to as a "point of imitation"; Strict imitation is called "canon." Musica Reservata: This term applies to High/Late Renaissance composers who "suited the music to the meaning of the words, expressing the power of each affection." Musica Transalpina: ("Music across the Alps") A printed anthology of Italian popular music translated into English and published in England in 1588. -

Notes on Heinrich Isaac's Virgo Prudentissima Author(S): Alejandro Enrique Planchart Source: the Journal of Musicology, Vol

Notes on Heinrich Isaac's Virgo prudentissima Author(s): Alejandro Enrique Planchart Source: The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Winter 2011), pp. 81-117 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jm.2011.28.1.81 Accessed: 26-06-2017 18:47 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Musicology This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Mon, 26 Jun 2017 18:47:45 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Notes on Heinrich Isaac’s Virgo prudentissima ALEJandro ENRIQUE PLANCHART Thomas Binkley in memoriam In 1520 Sigmund Grimm and Marx Wirsung published their Liber selectarum cantionum quas vulgo mutetas appellant, a choirbook that combined double impression printing in the manner of Petrucci with decorative woodcuts. As noted in the dedicatory letter by the printers and the epilogue by the humanist Conrad Peutinger, the music was selected and edited by Ludwig Senfl, who had succeeded his teacher, Heinrich Isaac, as head of Emperor Maximilian’s chapel 81 until the emperor’s death in 1519. -

Reception of Josquin's Missa Pange

THE BODY OF CHRIST DIVIDED: RECEPTION OF JOSQUIN’S MISSA PANGE LINGUA IN REFORMATION GERMANY by ALANNA VICTORIA ROPCHOCK Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Alanna Ropchock candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree*. Committee Chair: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Committee Member: Dr. L. Peter Bennett Committee Member: Dr. Susan McClary Committee Member: Dr. Catherine Scallen Date of Defense: March 6, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ........................................................................................................... i List of Figures .......................................................................................................... ii Primary Sources and Library Sigla ........................................................................... iii Other Abbreviations .................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... v Abstract ..................................................................................................................... vii Introduction: A Catholic -

Caput: Ockeghem & the English

Ockeghem@600 | Concert 5 CAPUT: OCKEGHEM & THE ENGLISH 8 PM • FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 2017 — First Parish of Lexington 8 PM • SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2017 — First Church in Cambridge, Congregational Ockeghem@600 | Concert 5 CAPUT: OCKEGHEM & THE ENGLISH OCKEGHEM & THE ENGLISH Johannes Ockeghem (c. 1420-1497) cantus In this fifth program of our multi-season survey particular the way in which it handles the Missa Caput Martin Near of the complete works of Johannes Ockeghem, two lower lines of its four-voice contrapuntal Laura Pudwell Kyrie • lp ms st dm / mn om jm pg we present one of his earliest surviving texture (labelled Tenor primus and secundus), Gloria • lp om jm pg works, the Missa Caput. Those who have influenced a generation of French and Flemish tenor & contratenor attended previous concerts in the series will composers. Ockeghem adopts the new manner John Pyamour (d. before March 1426) Owen McIntosh Quam pulcra es • om jm dm Jason McStoots perhaps share the impression we are forming of writing in four parts, but then ups the Mark Sprinkle of Ockeghem’s compositional character— technical ante considerably by the daring and Walter Frye (d. before June 1475) Sumner Thompson curious, experimental, boldly asserting novel use to which he puts the cantus firmus. • Alas alas alas is my chief song mn st pg his superior craft vis-à-vis his models by Ave regina celorum • lp ms dm bassus surpassing their technical achievements, and The cantus firmus melody quotes a long Ockeghem Paul Guttry stretching the theoretical systems of his time in melisma on the word “caput” from an antiphon Missa Caput David McFerrin ways that challenge our ability to find a definite sung during the foot-washing ceremony on Credo • mn jm st dm solution (and surely posed similar challenges Maundy Thursday in the Sarum rite. -

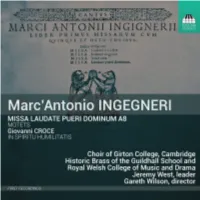

TOCC0556DIGIBKLT.Pdf

THE COUNCIL OF TRENT AND THE MUSIC OF MARC’ANTONIO INGEGNERI by Giampiero Innocente The Protestant Reformation was a storm which shook the Catholic church in every way: its dogmas, its hierarchies and the certainties of faith on which it had been based for 1,500 years were undermined at their very foundations. Luther and the reformers had called into question not only its theology and how it was articulated but also the nature of its community, its liturgy, its rituals and the music associated with them. A direct precursor of those musical changes was Luther’s translation of the Bible from Latin to German, completed in 1534, a work that became a true monument of the German language and a document that helped establish a ‘national’ identity. Although Luther had not totally rejected every musical form of the Catholic tradition – he preserved Latin hymns, for example – the new style of liturgical music he promoted was designed for a congregation that was no longer Catholic: the predominance of the Word of God, the abandonment of faith in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and communion understood as being taken only ‘in memory’ of Christ’s Last Supper were fundamental elements that emboldened the newly reformed Protestant worship and generated new musical forms which were peculiar, and central, to it. Faced with this turn of events, the Catholic church gathered itself in order to launch a powerful ‘counter-reformation’ of its own, and between 1545 and 1563 its senior cardinals and clergy were convened to meet over a series of 25 sessions, now known as the Council of Trent, in order to respond to the attacks of the Protestant world that were spreading rapidly in northern Europe. -

The Genres of Renaissance Music: 1420-1520

Chapter 5 The Genres of Renaissance Music: 1420-1520 Tuesday, September 4, 12 Sacred Vocal Music • principal genres: Mass and motet • cantus firmus technique supplanted isorhythm as chief structural device in large-scale vocal works • primary organizational techniques are: cantus firmus, canon, parody, & paraphrase Tuesday, September 4, 12 Sacred Vocal Music The Mass • emergence of the cyclic Mass - a cycle of all movements of the Mass Ordinary integrated by common cantus firmus or other musical device Tuesday, September 4, 12 Sacred Vocal Music Du Fay Missa Se la face • Guillaume Du Fay credited with six complete settings of the Mass - Missa Se la face ay pale written c. 1450 • first mass by any composer based on a cantus firmus from a secular source • one of the first masses in which tenor (line carrying cantus firmus) is not the lowest Tuesday, September 4, 12 Sacred Vocal Music Du Fay Missa Se la face • Based on Du Fay’s chanson Se la face • tenor uses a cantus firmus based on the chanson (see mm. 19, 125, & 165) • see Bonds p. 122, example 5-1 compare with the tenor in the Mass Gloria Tuesday, September 4, 12 Sacred Vocal Music The Mass: Ockeghem • Johannes Ockeghem’s Missa prolationum • almost every movement has each voice with its own mensuration • beginning of Kyrie I and Kyrie II, all four basic mensurations “prolations” are present, hence the name of the Mass Tuesday, September 4, 12 Sacred Vocal Music Ockeghem’s Missa prolationum • see Bonds p. 125 for manuscript • prolationum refers to something like beat- subdivision - mensuration signs, see Bonds p. -

Mid-Fifteenth-Century English Mass Cycles in Continental Sources, Vol

Mid-Fifteenth-Century English Mass Cycles in Continental Sources, vol. 1 James Matthew Cook Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2014 Abstract Fifteenth-century English music had a profound impact on mainland Europe, with several important innovations (e.g. the cyclic cantus firmus Mass) credited as English in origin. However, the turbulent history of the Church in England has left few English sources for this deeply influential repertory. The developing narrative surrounding apparently English technical innovations has therefore often focussed on the recognition of English works in continental manuscripts, with these efforts most recently crystallised in Curtis and Wathey’s ‘Fifteenth-Century English Liturgical Music: A List of the Surviving Repertory’. The focus of discussion until now has generally been on a dichotomy between English and continental origin. However, as more details emerge of the opportunities for cultural cross-fertilisation, it becomes increasingly clear that this may be a false dichotomy. This thesis re-evaluates the complex issues of provenance and diffusion affecting the mid-fifteenth-century cyclic Mass. By breaking down the polarization between English and continental origins, it offers a new understanding of the provenance and subsequent use of many Mass cycles. Contact between England and the continent was frequent, multifarious and quite possibly reciprocal and, despite strong national trends, there exists a body of work that can best be understood in relation to international cultural exchange. This thesis helps to clarify the i provenance of a number of Mass cycles, but also suggests that, for Masses such as the anonymous Thomas cesus and Du cuer je souspier, Le Rouge’s So ys emprentid, and even perhaps Bedyngham’s Sine nomine, cultural exchange is key to our understanding. -

Missa Sine Nomine

Guillaume Du Fay Opera Omnia 03/01 Missa sine nomine Edited by Alejandro Enrique Planchart Marisol Press Santa Barbara, 2008 Guillaume Du Fay Opera Omnia Edited by Alejandro Enrique Planchart 01 Cantilena, Paraphrase, and New Style Motets 02 Isorhythmic and Mensuration Motets 03 Ordinary and Plenary Mass Cycles 04 Proper Mass Cycles 05 Ordinary of the Mass Movements 06 Proses 07 Hymns 08 Magnificats 09 Benedicamus domino 10 Songs 11 Plainsongs 12 Dubious Works and Works with Spurious Attributions © Copyright 2008 by Alejandro Enrique Planchart, all rights reserved. Guillaume Du Fay, Missa sine nomine: 1 03/01 Missa sine nomine Kyrie eleison = Guillaume Du Fay Cantus Ky ri e e [ ] Contratenor 8 Ky ri e e [ ] Tenor 8 Ky ri e e 6 lei son. Ky ri e e 8 lei son. Ky ri e e 8 lei son. Ky ri e e 12 lei son. Ky ri e e 8 lei son. Ky ri e 8 lei son. Ky ri e 18 lei son, e lei son. 8 e lei son, e lei son. 8 e lei lei son, e lei son. 24 Chri ste e [ ] 8 Chri ste e [ ] 8 Chri ste e D-OO Guillaume Du Fay, Missa sine nomine: 2 29 lei son. Chri 8 lei son. Chri 8 lei son. Chri 34 ste e lei son. Chri 8 ste e lei son. Chri 8 ste e lei son. Chri 40 ste e lei son. 8 ste e lei son. 8 ste e lei son. 46 Ky ri e e 8 Ky ri e e 8 Ky ri e e 50 8 8 D-OO Guillaume Du Fay, Missa sine nomine: 3 54 lei son. -

The Status of the Early Polyphonic Mass

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-11412-7 - The Cultural Life of the Early Polyphonic Mass: Medieval Context to Modern Revival Andrew Kirkman Excerpt More information Part I The status of the early polyphonic Mass © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-11412-7 - The Cultural Life of the Early Polyphonic Mass: Medieval Context to Modern Revival Andrew Kirkman Excerpt More information 1 Enlightenment and beyond It takes a very bold and independent mind to conceive the idea that the invariable parts of the Mass should be composed not as separate items, but as a set of five musically coherent compositions. In the latter case the means of unification are provided by the composer, not the liturgy. This idea, which is the historical premise of the cyclic Ordinary, betrays the weakening of purely liturgical consideration and the strengthening of essentially aesthetic concepts. The “absolute” work of art begins to encroach on liturgical function. We discover here the typical Renaissance attitude – and it is indeed the Renaissance philosophy of art that furnishes the spiritual background to the cyclic Mass. The beginnings of the Mass cycle coincide with the beginnings of the musical Renaissance. It is therefore hardly surprising that the decisive turn in the development of the cyclic Mass occurred only in the early fifteenth century. At this time the first attempts are made to unify the movements of the Ordinary by means of the same musical material.1 Now more than half a century old, Bukofzer’s statement remains the classic evaluation of the “cyclic” polyphonic Mass as masterwork.