University Microfilms, a XERD\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(1) Western Culture Has Roots in Ancient and ___

5 16. (50) If a 14th-century composer wrote a mass. what would be the names of the movement? TQ: Why? Chapter 3 Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Agnus Dei. The text remains Roman Liturgy and Chant the same for each day throughout the year. 1. (47) Define church calendar. 17. (51) What is the collective title of the eight church Cycle of events, saints for the entire year services different than the Mass? Offices [Hours or Canonical Hours or Divine Offices] 2. TQ: What is the beginning of the church year? Advent (four Sundays before Christmas) 18. Name them in order and their approximate time. (See [Lent begins on Ash Wednesday, 46 days before Easter] Figure 3.3) Matins, before sunrise; Lauds, sunrise; Prime, 6 am; Terce, 9 3. Most important in the Roman church is the ______. am; Sext, noon; Nones, 3 pm; Vespers, sunset; Mass Compline, after Vespers 4. TQ: What does Roman church mean? 19. TQ: What do you suppose the function of an antiphon is? Catholic Church To frame the psalm 5. How often is it performed? 20. What is the proper term for a biblical reading? What is a Daily responsory? Lesson; musical response to a Biblical reading 6. (48) Music in Context. When would a Gloria be omitted? Advent, Lent, [Requiem] 21. What is a canticle? Poetic passage from Bible other than the Psalms 7. Latin is the language of the Church. The Kyrie is _____. Greek 22. How long does it take to cycle through the 150 Psalms in the Offices? 8. When would a Tract be performed? Less than a week Lent 23. -

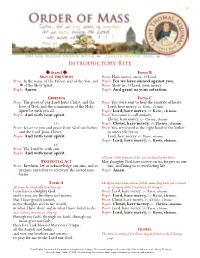

Stand Priest: in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy

1 Stand Form B SIGN OF THE CROSS Priest: Have mercy on us, O Lord. Priest: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and People: For we have sinned against you. ✠of the Holy Spirit. Priest: Show us, O Lord, your mercy. People: Amen. People: And grant us your salvation. GREETING Form C Priest: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the Priest: You were sent to heal the contrite of heart: love of God, and the communion of the Holy Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Spirit be with you all. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: And with your spirit. Priest: You came to call sinners: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Or: People: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Priest: Grace to you and peace from God our Father Priest: You are seated at the right hand of the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. to intercede for us: People: And with your spirit. Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Or: Priest: The Lord be with you. People: And with your spirit. All forms of the Penitential Act are concluded by the Priest: PENITENTIAL ACT May almighty God have mercy on us, forgive us our Priest: Brethren, let us acknowledge our sins, and so sins, and bring us to everlasting life. prepare ourselves to celebrate the sacred mys- People: Amen. teries. Form A The Kyrie eleison invocations follow, unless they have just occurred All pause for silent reflection then say: in a formula of the Penitential Act (Form C). -

Thanksgiving 1918

FORMS OF THANKSGIVING TO ALMIGHTY GOD TO BE USED ON SUNDAY, THE 17TH NOVEMBER, 1918 Being the Sunday after the cessation of hostilities between the Allied Powers and the German Empire. Issued under the Authority of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. ________________________________________________________________________ I THE ORDER OF HOLY COMMUNION ¶ In the Order of Holy Communion the Collects, Epistle, and Gospel following may be used: “O Almighty God, the Sovereign Commander of all the world.” &c. [Forms of Prayer to be used at Sea after Victory of Deliverance from an Enemy.] Collect of the 6th Sunday after the Epiphany. Collect of the 5th Sunday after Trinity. The Epistle: Philippians iv. 4-8, inclusive. The Gospel: St. John xii. 23-33, inclusive. ¶Before bidding the people to pray for the whole state of Christ’s Church militant here in earth, the Priest may say: Let us praise God for the great and glorious victory which he has been pleased to grant to us and to our Allies, and for the good hope of peace now shining through the clouds of war. Let us praise him for the faithfulness, bravery, and self-sacrifice of all who have fought and laboured for our deliverance, and, above all, for the memory and high example of the men who have died that we may live. Let us remember before God the solemn responsibility now resting upon the statesmen of the world, and pray that he may guide them by his spirit of counsel and of strength, and that by their endeavours peace and justice, freedom and order, may be established among all nations. -

Understanding When to Kneel, Sit and Stand at a Traditional Latin Mass

UNDERSTANDING WHEN TO KNEEL, SIT AND STAND AT A TRADITIONAL LATIN MASS __________________________ A Short Essay on Mass Postures __________________________ by Richard Friend I. Introduction A Catholic assisting at a Traditional Latin Mass for the first time will most likely experience bewilderment and confusion as to when to kneel, sit and stand, for the postures that people observe at Traditional Latin Masses are so different from what he is accustomed to. To understand what people should really be doing at Mass is not always determinable from what people remember or from what people are presently doing. What is needed is an understanding of the nature of the liturgy itself, and then to act accordingly. When I began assisting at Traditional Latin Masses for the first time as an adult, I remember being utterly confused with Mass postures. People followed one order of postures for Low Mass, and a different one for Sung Mass. I recall my oldest son, then a small boy, being thoroughly amused with the frequent changes in people’s postures during Sung Mass, when we would go in rather short order from standing for the entrance procession, kneeling for the preparatory prayers, standing for the Gloria, sitting when the priest sat, rising again when he rose, sitting for the epistle, gradual, alleluia, standing for the Gospel, sitting for the epistle in English, rising for the Gospel in English, sitting for the sermon, rising for the Credo, genuflecting together with the priest, sitting when the priest sat while the choir sang the Credo, kneeling when the choir reached Et incarnatus est etc. -

The Rites of Holy Week

THE RITES OF HOLY WEEK • CEREMONIES • PREPARATIONS • MUSIC • COMMENTARY By FREDERICK R. McMANUS Priest of the Archdiocese of Boston 1956 SAINT ANTHONY GUILD PRESS PATERSON, NEW JERSEY Copyright, 1956, by Frederick R. McManus Nihil obstat ALFRED R. JULIEN, J.C. D. Censor Lib1·or111n Imprimatur t RICHARD J. CUSHING A1·chbishop of Boston Boston, February 16, 1956 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA INTRODUCTION ANCTITY is the purpose of the "new Holy Week." The news S accounts have been concerned with the radical changes, the upset of traditional practices, and the technical details of the re stored Holy Week services, but the real issue in the reform is the development of true holiness in the members of Christ's Church. This is the expectation of Pope Pius XII, as expressed personally by him. It is insisted upon repeatedly in the official language of the new laws - the goal is simple: that the faithful may take part in the most sacred week of the year "more easily, more devoutly, and more fruitfully." Certainly the changes now commanded ,by the Apostolic See are extraordinary, particularly since they come after nearly four centuries of little liturgical development. This is especially true of the different times set for the principal services. On Holy Thursday the solemn evening Mass now becomes a clearer and more evident memorial of the Last Supper of the Lord on the night before He suffered. On Good Friday, when Holy Mass is not offered, the liturgical service is placed at three o'clock in the afternoon, or later, since three o'clock is the "ninth hour" of the Gospel accounts of our Lord's Crucifixion. -

The Penitential Rite & Kyrie

The Mass In Slow Motion Volumes — 7 and 8 The Penitential Rite & The Kyrie The Mass In Slow Motion is a series on the Mass explaining the meaning and history of what we do each Sunday. This series of flyers is an attempt to add insight and understanding to our celebration of the Sacred Liturgy. You are also invited to learn more by attending Sunday School classes for adults which take place in the school cafeteria each Sunday from 9:45 am. to 10:45 am. This series will follow the Mass in order. The Penitential Rite in general—Let us recall that we have just acknowledged and celebrated the presence of Christ among us. First we welcomed him as he walked the aisle of our Church, represented by the Priest Celebrant. The altar, another sign and symbol of Christ was then reverenced. Coming to the chair, a symbol of a share in the teaching and governing authority of Christ, the priest then announced the presence of Christ among us in the liturgical greeting. Now, in the Bible, whenever there was a direct experience of God, there was almost always an experience of unworthiness, and even a falling to the ground! Isaiah lamented his sinfulness and needed to be reassured by the angel (Is 6:5). Ezekiel fell to his face before God (Ez. 2:1). Daniel experienced anguish and terror (Dan 7:15). Job was silenced before God and repented (42:6); John the Apostle fell to his face before the glorified and ascended Jesus (Rev 1:17). Further, the Book of Hebrews says that we must strive for the holiness without which none shall see the Lord (Heb. -

The Agnus Dei

New and Corrected Translation of the Mass – Part 26 The Agnus Dei Lamb of God, Gen 22.8; Ex 12; 1 Cor 5.7 you take away the sins of the world, Lev 16.21; Jn 1.29 have mercy on us. Lamb of God, 1 Pet 1.19; Rev 5.6 you take away the sins of the world, 1 Jn 2.2 have mercy on us Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world, grant us peace. John 14.27; 20.26 Immediately after the Pax, the priest begins the Fraction, i.e. breaking the Host, which shows the death of Jesus, whose body was broken for us in the Sacrifice of the Cross (although not one of His bones was broken, cf. John 19.36). The priest takes a small particle of the Host and adds it to the Precious Blood in the chalice. This act, called the ‘commingling’, signifies the Resurrection, the coming together again of Christ’s Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity (even in death His Divinity remained united to all three preceding, which are part of His humanity). The Agnus Dei is a chant which accompanies the Fraction. Everyone says or sings it, using the words of St John the Baptist to point out Jesus as the Messiah. In the Eastern churches the sacrificial gifts are called “the Lamb”. It is the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist that moves us to call Jesus ‘Lamb of God’ at this point of the Mass, cf. “I saw a Lamb standing, as it were slain” (Rev 5.6). -

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there. -

SACRED MUSIC Volume 99, Number 1, Spring 1972 Cistercian Gradual (12Th Century, Paris, Bibl

SACRED MUSIC Volume 99, Number 1, Spring 1972 Cistercian Gradual (12th century, Paris, Bibl. Nat., ms . lat. 17,328) SACRED MUSIC Volume 99, Number 1 , Spring 1972 BERNSTEIN'S MASS 3 Herman Berlinski TU FELIX AUSTRIA 9 Reverend Robert Skeris MUSICAL SUPPLEMENT 13 REVIEWS 20 FROM THE EDITOR 25 NEWS 26 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caeci/ia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of publication: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minne sota 55103. Editorial office: Route 2, Box I, Irving, Texas 75062. Editorial Board Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O.Cist., Editor Mother C. A. Carroll, R.S.C.J. Rev. Lawrence Heiman, C.PP.S. J. Vincent Higginson Rev. Peter D. Nugent Rev. Elmer F. Pfeil Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler Frank D. Szynskie Editorial correspondence: Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O.Cist., Route 2, Box I, Irving, Texas 75062 News: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler, 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 Music for Review: Mother C. A. Carroll, R.S.C.J., Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart, Purchase, New York 10577 Rev. Elmer F. Pfeil 3257 South Lake Drive Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53207 Membership and Circulation: Frank D. Szynskie, Boys Town, Nebraska 68010 AdvertisinR: Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O.Cist. CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Dr. Roger Wagner Vice-president Noel Goemanne General Secretary Rev. Robert A. Skeris Treasurer Frank D. Szynskie Directors Robert I. -

The Credo the Rt

The Diocese of the Mid-Atlantic States Of the Anglican Catholic Church The credo The Rt. Rev’d D. Francis Lerow, Managing Editor The Rev’d Fr. T.L. Crowder, Content Editor Saint Aidan, Bishop and Confessor 31 August, A.D. 2015 The Crozier The Right Rev’d D. Francis Lerow, Bishop Ordinary Missions and Decisions, Planning and Money For many of our parishes, renewal tends to be an ongoing affair. We think very hard about our home parish. All of us want our church to have impact on the community and our community to have greater access to worship and the Traditional Anglican way. We depend on our vestries to drive the wagon that ensures that proper planning and resources are available to support the annual plan established at the Annual Parish Meetings. The problem with planning is that it quickly can lose the interest of the members of the parish. It is easy to fall back into our old ways, thinking that the Sunday Worship Service is all we need to bring them to Christ and eventually membership in the Church. Or if we have a young electrifying priest that will lead the way all will be well. It would be nice if it was that easy. But, we all know it is not. So what does it take? What kind of investment of time and resources does it take to really make things happen? What will cause the kind of renewal for which we all hope and pray? The business metric used to determine the effort and cost to sell a particular item of merchandise, as a rule of thumb, is to measure how many times their product gets the attention of a potential buyer. -

ETHEL MARY SMYTH DBE, Mus.Doc, D.Litt. a MUSICAL

ETHEL MARY SMYTH DBE, Mus.Doc, D.Litt. A MUSICAL TIMELINE compiled by Lewis Orchard Early days & adolescence in Frimley 1858 Born 22 April at 5 Lower Seymour Street (now part of Wigmore Street), Marylebone, London; daughter of Lieutenant Colonel (then) John Hall Smyth of the Bengal Artillery and Emma (Nina) Smyth. Ethel liked to claim that she was born on St. George's Day 23 April but her birth certificate clearly states 22 April. Baptised at St. Marylebone parish church on 28 May, 1858. On return of father from India the family took up residence at Sidcup Place, Sidcup, Kent where she spent her early years up to age 9. Mostly educated by a series of governesses 1867 When father promoted to an artillery command at Aldershot the family moved to a large house 'Frimhurst' at Frimley Green, Surrey, which later he purchased. Sang duets with Mary at various functions and displayed early interest in music. 1870 'When I was 12 a new victim (governess) arrived who had studied music at the Leipzig Conservatorium'. This was Marie Louise Schultz of Stettin, Pomerania, Germany (now Szezecin, Poland) who encouraged her interest in music and introduced her to the works of the major (German) composers, notably Beethoven.. Later Ethel met Alexander Ewing (also in the army at Aldershot in the Army Service Corps). Ethel became acquainted with him through Mrs Ewing who was a friend of her mother. Ewing was musically well educated and was impressed by Ethel's piano playing and compositions. He encouraged her in her musical ambitions. He taught her harmony and introduced her to the works of Brahms, List, Wagner and Berlioz and gave her a copy of Berlioz's 'Treatise on Orchestration'. -

Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 As a Stylistic Guide

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2008 Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide Jonathan Candler Kilgore University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Composition Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Kilgore, Jonathan Candler, "Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide" (2008). Dissertations. 1129. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC GUIDE by Jonathan Candler Kilgore A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts August 2008 COPYRIGHT BY JONATHAN CANDLER KILGORE 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC