Large Firm Dynamics and Secular Stagnation: Evidence from Japan and the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

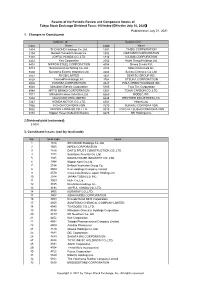

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

Itraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List March 2021

iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List March 2021 Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 1 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List...........................................3 2 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final vs. Series 34................................................ 5 3 Further information .....................................................................................6 Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 2 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 1 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List IHS Markit Ticker IHS Markit Long Name ACOM ACOM CO., LTD. JUSCO AEON CO., LTD. ANAHOL ANA HOLDINGS INC. FUJITS FUJITSU LIMITED HITACH HITACHI, LTD. HNDA HONDA MOTOR CO., LTD. CITOH ITOCHU CORPORATION JAPTOB JAPAN TOBACCO INC. JFEHLD JFE HOLDINGS, INC. KAWHI KAWASAKI HEAVY INDUSTRIES, LTD. KAWKIS KAWASAKI KISEN KAISHA, LTD. KINTGRO KINTETSU GROUP HOLDINGS CO., LTD. KOBSTL KOBE STEEL, LTD. KOMATS KOMATSU LTD. MARUB MARUBENI CORPORATION MITCO MITSUBISHI CORPORATION MITHI MITSUBISHI HEAVY INDUSTRIES, LTD. MITSCO MITSUI & CO., LTD. MITTOA MITSUI CHEMICALS, INC. MITSOL MITSUI O.S.K. LINES, LTD. NECORP NEC CORPORATION NPG-NPI NIPPON PAPER INDUSTRIES CO.,LTD. NIPPSTAA NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION NIPYU NIPPON YUSEN KABUSHIKI KAISHA NSANY NISSAN MOTOR CO., LTD. OJIHOL OJI HOLDINGS CORPORATION ORIX ORIX CORPORATION PC PANASONIC CORPORATION RAKUTE RAKUTEN, INC. RICOH RICOH COMPANY, LTD. SHIMIZ SHIMIZU CORPORATION SOFTGRO SOFTBANK GROUP CORP. SNE SONY CORPORATION Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 3 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List SUMICH SUMITOMO CHEMICAL COMPANY, LIMITED SUMI SUMITOMO CORPORATION SUMIRD SUMITOMO REALTY & DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. TFARMA TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANY LIMITED TOKYOEL TOKYO ELECTRIC POWER COMPANY HOLDINGS, INCORPORATED TOSH TOSHIBA CORPORATION TOYOTA TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION Copyright © 2021 IHS Markit Ltd | 4 T180614 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final Membership List 2 iTraxx Japan Series 35 Final vs. -

Ranking of Stocks by Market Capitalization(As of End of Jan.2018)

Ranking of Stocks by Market Capitalization(As of End of Jan.2018) 1st Section Rank Code Issue Market Capitalization \100mil. 1 7203 TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION 244,072 2 8306 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group,Inc. 115,139 3 9437 NTT DOCOMO,INC. 105,463 4 9984 SoftBank Group Corp. 98,839 5 6861 KEYENCE CORPORATION 80,781 6 9432 NIPPON TELEGRAPH AND TELEPHONE CORPORATION 73,587 7 9433 KDDI CORPORATION 71,225 8 7267 HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 69,305 9 8316 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group,Inc. 68,996 10 7974 Nintendo Co.,Ltd. 67,958 11 7182 JAPAN POST BANK Co.,Ltd. 66,285 12 6758 SONY CORPORATION 65,927 13 6954 FANUC CORPORATION 60,146 14 7751 CANON INC. 58,005 15 6902 DENSO CORPORATION 54,179 16 4063 Shin-Etsu Chemical Co.,Ltd. 53,624 17 8411 Mizuho Financial Group,Inc. 52,124 18 6594 NIDEC CORPORATION 52,025 19 9983 FAST RETAILING CO.,LTD. 51,647 20 4502 Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited 50,743 21 7201 NISSAN MOTOR CO.,LTD. 49,108 22 8058 Mitsubishi Corporation 48,497 23 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 48,159 24 6098 Recruit Holdings Co.,Ltd. 45,095 25 5108 BRIDGESTONE CORPORATION 43,143 26 6503 Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 42,782 27 9022 Central Japan Railway Company 42,539 28 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 41,877 29 9020 East Japan Railway Company 41,824 30 6301 KOMATSU LTD. 41,162 31 3382 Seven & I Holdings Co.,Ltd. 39,765 32 6752 Panasonic Corporation 39,714 33 4661 ORIENTAL LAND CO.,LTD. 38,769 34 8766 Tokio Marine Holdings,Inc. -

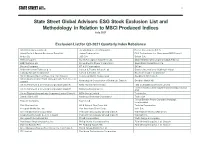

State Street Global Advisors ESG Stock Exclusion List and Methodology in Relation to MSCI Produced Indices July 2021

1 State Street Global Advisors ESG Stock Exclusion List and Methodology in Relation to MSCI Produced Indices July 2021 Exclusion List for Q3-2021 Quarterly Index Rebalance Adani Enterprises Limited Jacobs Engineering Group Inc. Reinet Investments S.C.A. Adani Ports & Special Economic Zone Ltd. Japan Tobacco Inc. RLX Technology, Inc. Sponsored ADR Class A Airbus SE JBS S.A. Safran S.A. Altria Group Inc Korea Aerospace Industries, Ltd. Saudi Arabian Oil Company (Saudi Aramco) BAE Systems plc Korea Electric Power Corporation Saudi Basic Industries Corp. Boeing Company KT & G Corporation SK Inc. British American Tobacco p.l.c. Larsen & Toubro Infotech Ltd Smoore International Holdings Limited Canopy Growth Corporation Larsen & Toubro Ltd. Southern Copper Corporation China National Nuclear Power Co. Ltd. Class A Lockheed Martin Corporation Swedbank AB Class A China Northern Rare Earth (Group) High-Tech Co., Ltd. Metallurgical Corporation of China Ltd. Class A Swedish Match AB Class A China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation Class A MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC Tata Consultancy Services Limited Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Limited Sponsored China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation Class H Motorola Solutions, Inc. ADR China Shipbuilding Industry Company Limited Class A MTN Group Limited Textron Inc. Danske Bank A/S Northrop Grumman Corporation Thales SA Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, Eastern Company Nutrien Ltd. Incorporated Elbit Systems Ltd Oil & Natural Gas Corp. Ltd. Toshiba Corporation Freeport-McMoRan, Inc. Pan American Silver Corp. Vale S.A. General Dynamics Corporation PetroChina Company Limited Class A Wal-Mart de Mexico SAB de CV Grupo Mexico S.A.B. de C.V. Class B PetroChina Company Limited Class H Walmart Inc. -

Annual Report FY2017

Corporate Information 048 Corporate Governance 058 History of the JT Group Japan Tobacco Inc. Annual Report FY2017 062 Regulation and Other Relevant Laws Year ended December 31, 2017 065 Litigation 066 Members of the Board, Audit Investment Operations & Analysis and Supervisory Board Members, leading and Executive Officers to sustainable 018 Industry Overview 067 Members of the JTI growth. 018 Tobacco Business Executive Committee 021 Pharmaceutical Business 067 Corporate Data 021 Processed Food Business 068 Investor Relations Activity 022 Review of Operations 069 Shareholder Information 022 International Tobacco Business 028 Japanese Domestic Tobacco Business 032 Global Tobacco Strategy 034 Pharmaceutical Business 038 Processed Food Business 040 Risk Factors Management 044 JT Group and Sustainability 046 Environmental, Social and 001 Performance Indicators Governance Initiatives 002 At a Glance 004 Consolidated Five-Year Financial Summary 006 Message from the Chairman and CEO Financial Information 008 CEO Business Review 010 Highlights (JT Group’s 2017) 071 Message from CFO 012 Management Principle, Strategic 072 Financial Review Framework and Resource Allocation 080 Consolidated Financial Statements 014 Business Plan 2018 086 Notes to Consolidated 015 Role and Target of Each Business Financial Statements 016 Performance Measures 139 Independent Auditor’s report 140 Glossary of Terms Management Performance Indicators Adjusted Operating Profit Dividend per Share 585.3 14 0 (JPY BN) (JPY) - 0.3% +7. 7 % Year-on-Year Change Year-on-Year Change - 0.6% Factsheets available at: Year-on-Year Change at Constant Exchange Rates https://www.jt.com/investors/results/annual_report/ Unless the context indicates otherwise, references in this Annual Report to ‘we’, ‘us’, In addition, these forward-looking statements are necessarily dependent upon ‘our’, ‘Japan Tobacco’, ‘JT Group’ or ‘JT’ are to Japan Tobacco Inc. -

International Companies with U.S. Branches

INTERNATIONAL COMPANIES WITH U.S. BRANCHES ® CLEMSON UNIVERSITY MICHELIN CAREER CENTER Company: Home Country: Type of Business: Royal Dutch/Shell Group Netherlands oil & gas Royal Dutch/Shell Group United Kingdom oil & gas BP United Kingdom oil & gas DaimlerChrysler Germany automobile Toyota Motor Japan automobile Mitsubishi Japan trading & distribution Mitsui & Co Japan trading & distribution Allianz Worldwide Germany insurance ING Group Netherlands diversified finance Volkswagen Group Germany automobile Sumitomo Japan trading & distribution Marubeni Japan trading & distribution Hitachi Japan electronic equipment Honda Motor Japan automobile AXA Group France insurance Sony Japan household durables Ahold Netherlands food & drug retail Nestle Switzerland food products Nissan Motor Japan automobile Credit Suisse Group Switzerland diversified finance Deutsche Bank Group Germany diversified finance BNP Paribas France bank Deutsche Telekom Germany telecom services Aviva United Kingdom insurance Generali Group Italy insurance Samsung Electronics South Korea semiconductor equip & prods Vodafone United Kingdom wireless telecom svcs Toshiba Japan electronic equipment ENI Italy oil & gas Unilever Netherlands food products Unilever United Kingdom food products Fortis Netherlands diversified finance France Telecom France telecom services UBS Switzerland diversified finance HSBC Group United Kingdom bank BMW-Bayerische Motor Germany automobile NEC Japan computers & peripherals Fujitsu Japan computers & peripherals Bayer HypoVereinsbank Germany bank -

R&Co Risk-Based International Index – Weighting

Rothschild & Co Risk-Based International Index Indicative Index Weight Data as of June 30, 2021 on close Constituent Exchange Country Index Weight(%) Jardine Matheson Holdings Ltd Singapore 1.46 LEG Immobilien SE Germany 0.98 Ajinomoto Co Inc Japan 0.95 SoftBank Corp Japan 0.89 Shimano Inc Japan 0.85 FUJIFILM Holdings Corp Japan 0.73 Singapore Exchange Ltd Singapore 0.72 Japan Tobacco Inc Japan 0.72 Cellnex Telecom SA Spain 0.69 Nintendo Co Ltd Japan 0.69 Carrefour SA France 0.67 Nexon Co Ltd Japan 0.66 Deutsche Wohnen SE Germany 0.65 Bank of China Ltd Hong Kong 0.64 REN - Redes Energeticas Nacion Portugal 0.63 Pan Pacific International Hold Japan 0.63 Japan Post Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.62 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C Japan 0.61 Roche Holding AG Switzerland 0.61 Nestle SA Switzerland 0.61 Novo Nordisk A/S Denmark 0.59 ENEOS Holdings Inc Japan 0.59 Nomura Research Institute Ltd Japan 0.59 Koninklijke Ahold Delhaize NV Netherlands 0.59 Jeronimo Martins SGPS SA Portugal 0.58 HelloFresh SE Germany 0.58 Toshiba Corp Japan 0.58 Hoya Corp Japan 0.58 Siemens Healthineers AG Germany 0.58 MS&AD Insurance Group Holdings Japan 0.57 Coloplast A/S Denmark 0.57 Kerry Group PLC Ireland 0.57 Scout24 AG Germany 0.57 SG Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.56 Symrise AG Germany 0.56 Nitori Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.56 Beiersdorf AG Germany 0.55 Mitsubishi Corp Japan 0.55 KDDI Corp Japan 0.55 Sysmex Corp Japan 0.55 Chr Hansen Holding A/S Denmark 0.55 Ping An Insurance Group Co of Hong Kong 0.55 Eisai Co Ltd Japan 0.54 Chocoladefabriken Lindt & Spru Switzerland 0.54 Givaudan -

Bribery & Corruption

Bribery & Corruption First Edition Contributing Editors: Jonathan Pickworth & Deborah Williams Published by Global Legal Group CONTENTS Preface Jonathan Pickworth & Deborah Williams, Dechert LLP Albania Silva Velaj & Sabina Lalaj, Boga & Associates 1 Argentina Marcelo den Toom & Mercedes de Artaza, M. & M. Bomchil 7 Australia Justin McDonnell, David Eliakim & Natalie Caton, King & Wood Mallesons 15 Bangladesh Dr. Kamal Hossain, Dr. Kamal Hossain and Associates 25 Belgium Joost Everaert, Nanyi Kaluma & Anthony Verhaegen, Allen & Overy LLP 30 Brazil Maurício Zanoide de Moraes, Caroline Braun & Daniel Diez Castilho, Zanoide de Moraes, Peresi & Braun Advogados Associados 36 Canada Mark Morrison, Paul Schabas & Michael Dixon, Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP 44 Cayman Islands Martin Livingston & Brett Basdeo, Maples and Calder 52 China David Tiang, King & Wood Mallesons 60 Czech Republic Helena Hailichová & Eva Haisová, Johnson Šťastný Kramařík, advokátní kancelář, s.r.o. 70 France Julia Minkowski & Romain Fournier, Temime & Associés 78 Germany Sascha Kuhn, Simmons & Simmons LLP 87 Hong Kong Kyle Wombolt, Robert Hunt & Janice Tsang, Herbert Smith Freehills 95 India Siddharth Thacker, Mulla & Mulla & Craigie Blunt & Caroe 105 Indonesia Kyle Wombolt, Charles Ball & Narendra Adiyasa, Hiswara Bunjamin & Tandjung (HBT) in association with Herbert Smith Freehills 113 Ireland Megan Hooper & Heather Mahon, McCann FitzGerald 121 Italy Roberta Guaineri & Francesca Federici, Moro Visconti de Castiglione Guaineri 131 Japan Daiske Yoshida & Junyeon Park, Latham & Watkins 142 Mexico Edgar M. Anaya & Paula Nava González, Anaya Abogados Asociados, S.C. 151 Singapore Ing Loong Yang & Tina Wang, Latham & Watkins 160 South Africa Dave Loxton, Werksmans Attorneys 168 Spain Esteban Astarloa & Patricia Leandro, Uría Menéndez Abogados 176 Switzerland Grégoire Mangeat & Fanny Margairaz, Eversheds Ltd 186 Thailand Kyle Wombolt, Chinnawat Thongpakdee & Michelle Yu, Herbert Smith Freehills (Thailand) Ltd 197 Turkey Gönenç Gürkaynak & Ç. -

R&Co Risk-Based Japan Index

Rothschild & Co Risk-Based Japan Index Indicative Index Weight Data as of June 30, 2021 on close Constituent Exchange Country Index Weight(%) McDonald's Holdings Co Japan L Japan 1.29 Idemitsu Kosan Co Ltd Japan 1.12 SoftBank Corp Japan 1.05 Nintendo Co Ltd Japan 0.86 Hitachi Metals Ltd Japan 0.83 Yakult Honsha Co Ltd Japan 0.82 Iwatani Corp Japan 0.81 ENEOS Holdings Inc Japan 0.79 FUJIFILM Holdings Corp Japan 0.78 KDDI Corp Japan 0.75 Toshiba Corp Japan 0.73 Calbee Inc Japan 0.73 Ajinomoto Co Inc Japan 0.72 Eisai Co Ltd Japan 0.72 Nissin Foods Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.71 Morinaga Milk Industry Co Ltd Japan 0.70 Japan Tobacco Inc Japan 0.66 H.U. Group Holdings Inc Japan 0.66 JCR Pharmaceuticals Co Ltd Japan 0.64 MEIJI Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.64 Yamazaki Baking Co Ltd Japan 0.63 Chugoku Electric Power Co Inc/ Japan 0.63 Nippon Gas Co Ltd Japan 0.63 PeptiDream Inc Japan 0.62 Chubu Electric Power Co Inc Japan 0.62 Seven & i Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.62 FP Corp Japan 0.61 Pola Orbis Holdings Inc Japan 0.61 Lion Corp Japan 0.61 Shiseido Co Ltd Japan 0.60 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C Japan 0.60 Nichirei Corp Japan 0.59 Japan Post Bank Co Ltd Japan 0.59 Kobayashi Pharmaceutical Co Lt Japan 0.59 Anritsu Corp Japan 0.58 Skylark Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.58 Kyowa Kirin Co Ltd Japan 0.58 Lawson Inc Japan 0.58 Suntory Beverage & Food Ltd Japan 0.57 Kinden Corp Japan 0.57 MS&AD Insurance Group Holdings Japan 0.56 Shimano Inc Japan 0.56 Mitsubishi Corp Japan 0.56 Zensho Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.56 Tokai Carbon Co Ltd Japan 0.56 Japan Post Holdings Co Ltd -

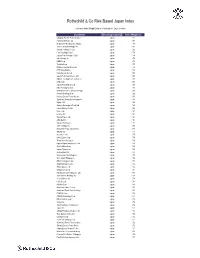

Rothschild & Co Risk-Based Japan Index

Rothschild & Co Risk-Based Japan Index Indicative Index Weight Data as of January 31, 2020 on close Constituent Exchange Country Index Weight (%) Chugoku Electric Power Co Inc/ Japan 1.01 Yamada Denki Co Ltd Japan 0.91 McDonald's Holdings Co Japan L Japan 0.88 Sushiro Global Holdings Ltd Japan 0.82 Skylark Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.82 Fast Retailing Co Ltd Japan 0.78 Japan Post Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.78 Ain Holdings Inc Japan 0.78 KDDI Corp Japan 0.77 Toshiba Corp Japan 0.75 Mizuho Financial Group Inc Japan 0.74 NTT DOCOMO Inc Japan 0.73 Kobe Bussan Co Ltd Japan 0.72 Japan Post Insurance Co Ltd Japan 0.69 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C Japan 0.69 LINE Corp Japan 0.69 Japan Post Bank Co Ltd Japan 0.68 Nitori Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.67 MS&AD Insurance Group Holdings Japan 0.66 Konami Holdings Corp Japan 0.66 Kyushu Electric Power Co Inc Japan 0.65 Sumitomo Realty & Development Japan 0.65 Fujitsu Ltd Japan 0.63 Suntory Beverage & Food Ltd Japan 0.63 Japan Airlines Co Ltd Japan 0.62 NEC Corp Japan 0.61 Lawson Inc Japan 0.60 Sekisui House Ltd Japan 0.60 ABC-Mart Inc Japan 0.60 Kyushu Railway Co Japan 0.60 ANA Holdings Inc Japan 0.59 Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Lt Japan 0.58 ORIX Corp Japan 0.57 Secom Co Ltd Japan 0.57 Seiko Epson Corp Japan 0.56 Trend Micro Inc/Japan Japan 0.56 Nippon Paper Industries Co Ltd Japan 0.56 Suzuki Motor Corp Japan 0.56 Japan Tobacco Inc Japan 0.55 Aozora Bank Ltd Japan 0.55 Sony Financial Holdings Inc Japan 0.55 West Japan Railway Co Japan 0.54 MEIJI Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.54 Sugi Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.54 Tokyo -

Characteristics and Attribution

The Dealer Marketing Report for the month ended: 08/31/2021 *Portfolio breakdown percentages are based on net assets. Complete portfolio holdings are available at www.alliancebernstein.com. AB FCP I - Japan Strategic Value Portfolio As of: 08/31/2021 9562 Asset Type Food Products 2.80% Japan 100.00% Tobacco 1.62% Total Investments 100.00% Equity 98.65% Personal Products 1.57% Cash/Currency 1.35% SUBTOTAL 12.99% Net Currency Exposure Breakdown Information Technology 100.00% IT Services 4.87% Japanese Yen 99.98% Top 10 Equity Holdings w/Sector Semiconductors & 2.74% United States Dollar 0.02% Semiconductor Equipment 1. Nippon Telegraph & Communication 4.97% Electronic Equipment, 1.76% Total Net Assets 100.00% Telephone Corp. Services Instruments & Components 2. Nippon Shinyaku Health Care 3.39% Software 0.86% Portfolio Statistics Co., Ltd. SUBTOTAL 10.23% 3. Mitsubishi UFJ Financials 3.31% Communication Services Total Number of Holdings 53 Financial Group, Inc. 4. Honda Motor Co., Consumer 3.20% Diversified Telecommunication 4.98% Active Share 83% Ltd. Discretionary Services 5. Mitsubishi Corp. Industrials 3.11% Entertainment 2.44% 6. Sony Group Corp. Consumer 3.01% Interactive Media & Services 0.51% Discretionary SUBTOTAL 7.93% 7. Mitsui Fudosan Co., Real Estate 2.78% Financials Ltd. Banks 5.74% 8. ENEOS Holdings, Energy 2.77% Diversified Financial Services 2.06% Inc. SUBTOTAL 7.80% 9. SCREEN Holdings Information 2.74% Co., Ltd. Technology Materials 10. Suzuki Motor Corp. Consumer 2.72% Chemicals 5.24% Discretionary Metals & Mining 1.02% -

Annual Report 2008 3 Corporate Social Responsibility Towards Achieving Our Corporate Vision

Annual Report 2008 ANNUAL REPORT For the Year Ended March 31, 2008 Domestic Tobacco Business CONTENTS 1 Financial Highlights 2 JT at a Glance 4 Towards Achieving Our Corporate Vision 6 To Our Stakeholders 10 Special Feature 12 The New JTI 16 Review of Operations 18 Domestic Tobacco Business 20 International Tobacco Business 22 Pharmaceutical Business 24 Foods Business 26 History of JT, Business Environment for JT 28 History of JT 30 Business Environment for JT 38 Corporate Social Responsibility 40 Corporate Governance 44 Activities Contributing to the Environment and Society 50 Financial Information 52 Consolidated Five-Year Financial Summary 54 Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Business Results 66 Consolidated Balance Sheets 68 Consolidated Statements of Income 69 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Equity 71 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows 72 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 98 Independent Auditors’ Report 99 Fact Sheets 100 Financial Data 106 Domestic Tobacco Business 116 International Tobacco Business 118 Pharmaceutical Business 119 Foods Business 119 Number of Employees 120 Shareholder Information 122 Members of the Board, Auditors, and Executive Officers 123 Corporate Data FORWARD-LOOKING AND CAUTIONARY STATEMENTS This presentation contains forward-looking statements about our industry, business, plans and objectives, financial condition and results of operations that are based on our current expectations, assump- tions, estimates and projections. These statements discuss future expectations, identify strategies, discuss market trends, contain projections of results of operations or of our financial condition, or state other forward-looking information. These forward-looking statements are subject to various known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors that could cause our actual results to differ materially from those suggested by any forward-looking statement.