'A War for a Better Tomorrow': Ms. Marvel Fanworks As Protest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRUMP Can't Let GO of Perceived Slights

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 3, 2016 ANALYSIS THE LEADING INDEPENDENT DAILY IN THE ARABIAN GULF ESTABLISHED 1961 Founder and Publisher YOUSUF S. AL-ALYAN Editor-in-Chief ABD AL-RAHMAN AL-ALYAN EDITORIAL : 24833199-24833358-24833432 ADVERTISING : 24835616/7 FAX : 24835620/1 CIRCULATION : 24833199 Extn. 163 ACCOUNTS : 24835619 COMMERCIAL : 24835618 P.O.Box 1301 Safat,13014 Kuwait. E MAIL :[email protected] Website: www.kuwaittimes.net Washington Watch Didi’s dominance over Uber offers roadmap for rivals By Brad Brooks hina ride-hailing service Didi Chuxing’s domi- nance of Uber Technologies in the China market Cmay provide a playbook for regional rivals to fend off the biggest US ride-hailing company, especially in Southeast Asia and India. The two companies on Monday confirmed the sale of Uber China to its bigger rival, ending a two-year, money-losing effort to break into one of the world’s toughest markets. Uber leaves with around a one-fifth stake in Didi, but will give up control of its China operations. Didi had a head start and maintained the lead on Uber with a strategy that other rivals may emulate, analysts and investors said. Didi counts two of the most powerful, best capital- ized Chinese Internet companies as backers; has tight connections with local government; made an ally of Trump can’t let go of perceived slights local taxi drivers and expanded into services such as buses that Uber ignored; and exploited its knowledge By Julie Pace awarded a Bronze Star and Purple Heart after his death in attacked” by Khizr Khan. Trump’s unwillingness to let the of local culture and consumers. -

NEW THIS WEEK from MARVEL... Star Wars Vader Dark Visions #1 (Of

NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL... Star Wars Vader Dark Visions #1 (of 5) Amazing Spider-Man #16.HU Avengers #16 (War of Realms) Avengers No Road Home #4 (of 10) Conan the Barbarian #4 Cosmic Ghost Rider Destroys Marvel History #1 (of 6) Uncanny X-Men #13 Domino Hotshots #1 (of 5) Immortal Hulk #14 Age of X-Man Prisoner-X #1 (of 5) Meet the Skrulls #1 (of 5) Star Wars #62 Champions #3 Deadpool #10 Miles Morales Spider-Man #1 (3rd print) Star Wars Age of Republic Padme Amidala #1 Black Order #5 (of 5) Fantastic Four Vol. 1 "Fourever" GN Killmonger #5 (of 5) Immortal Hulk #12 (2nd print) Ziggy Pig Silly Seal Comics #1 Avengers by Jason Aaron Vol. 2 GN Marvel Knights Punisher by Ennis Complete Collection Vol. 2 GN NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC... Detective Comics 80 Years of Batman Deluxe Hard Cover Doomsday Clock #9 (of 12) Batman #66 Green Lantern #5 Justice League #19 Harley Quinn #59 Young Justice #3 Adventures of the Super Sons #8 (of 12) Deathstroke #41 Green Arrow #50 Female Furies #2 (of 6) Dreaming #7 Curse of Brimtstone #12 Suicide Squad Black Files #5 (of 6) Batman & Harley Quinn GN Justice League Dark Vol. 1 GN JLA New World Order Essential Edition GN DC Essentials Batgirl Action Figure NEW THIS WEEK FROM IMAGE... Walking Dead #189 Walking Dead Vol. 31 GN Die #4 Cemetery Beach #7 (of 7) Deadly Class #37 Paper Girls #26 Unnatural #8 (of 12) Self Made #4 Eclipse #13 Vindication #2 (of 4) Last Siege GN Wicked & Divine Vol. -

Avengersassembly Orientation

By Preeti Chhibber Illustrated by James Lancett Scholastic Inc. © 2020 MARVEL All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. scholastic and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBN 978-1-338-58725-8 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 20 21 22 23 24 Printed in the U.S.A. 23 First printing 2020 Book design by Katie Fitch HERO CARD #148 powers NAME: KAMALA KHAN, AKA MS. MARVEL POWERS: Embiggening! Disembiggening! Stretching! Shape-shifting! ms. marvel HERO CARD #477 powers NAME: MILES MORALES, AKA ULTIMATE SPIDER-MAN POWERS: Wall-crawling, expo- nential strength, electric shocks, being invisible, but not being creepy like a spider, that is for sure. spider-man HERO CARD #091 powers NAME: DOREEN GREEN, AKA SQUIRREL GIRL POWERS: Powers of a squirrel and (more importantly) powers of a girl. -

Racial Literacy Curriculum Parent/Guardian Companion Guide

Pollyanna Racial Literacy Curriculum PARENT/GUARDIAN COMPANION GUIDE ©2019 Pollyanna, Inc. – Parent/Guardian Companion Guide | Monique Vogelsang, Primary Contributor CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Why is important to learn about and discuss race? 1 What is the Racial Literacy Curriculum? 1 How is the Curriculum Structured? 2 What is the Parent/Guardian Companion Guide? 2 How is the Companion Guide Structured? 3 Quick Notes About Terminology 3 UNITS The Physical World Around Us 5 A Celebration of (Skin) Colors We Are Part of a Larger Community 9 Encouraging Kindness, Social Awareness, and Empathy Diversity Around the World 13 How Geography and Our Daily Lives Connect Us Stories of Activism 17 How One Voice Can Change a Community (and Bridge the World) The Development of Civilization 24 How Geography Gave Some Populations a Head Start (Dispelling Myths of Racial Superiority) How “Immigration” Shaped the Racial and 29 Cultural Landscape of the United States The Persecution, Resistance, and Contributions of Immigrants and Enslaved People The Historical Construction of Race and 36 Current Racial Identities Throughout U.S. Society The Danger of a Single Story What is Race? 48 How Science, Society, and the Media (Mis)represent Race Please note: This document is strictly private, confidential Race as Primary “Institution” of the U.S. 55 and should not be copied, distributed or reproduced in How We May Combat Systemic Inequality whole or in part, nor passed to any third party outside of your school’s parents/guardians, without the prior consent of Pollyanna. PAGE ii ©2019 Pollyanna, Inc. – Parent/Guardian Companion Guide | Monique Vogelsang, Primary Contributor INTRODUCTION Why is it important to learn about and discuss race? Educators, sociologists, and psychologists recommend that we address concepts of race and racism with our children as soon as possible. -

Cheers and Jeers: Left Behind

Cheers and Jeers: Left behind Marty Trillhaase/Lewiston Tribune JEERS ... to Idaho Gov. C.L. "Butch" Otter. His decision to replace Bill Goesling of Moscow with Albertsons executive Andrew Scoggin of Boise leaves north central Idaho the odd man out on the State Board of Education. The governor is under no legal obligation to maintain a geographical balance on the state board. But certainly that's been the practice. In fact, someone from Latah County has served on the state board since 1991, when then-Gov. Cecil D. Andrus appointed attorney Roy Mosman. In 1998, Gov. Phil Batt replaced an ailing Mosman with former House Speaker Tom Boyd, R-Genesee. Three years later, Gov. Dirk Kempthorne appointed former Moscow Mayor Paul Agidius. And five years ago, Otter selected Goesling. Geography is not destiny. For instance, there is no more ardent advocate for the University of Idaho than state board President Emma Atchley of Ashton, a former president of the UI Foundation. Still, of the seven people Otter has named to the state board, three - former West Ada School Superintendent Linda Clark and former Idaho National Laboratory Deputy Director David Hill and now Scoggin - are from Ada County. That leaves just one northerner - Don Soltman of Twin Lakes, north of Coeur d'Alene - on the state board. This involves a vast area running from the Ada County line to Worley. It encompasses two of Idaho's four institutions of higher learning. Why is Otter ignoring it? JEERS ... to Otter, again. The governor has a bad habit. Rather than rely on Attorney General Lawrence Wasden's staff, Otter prefers to burn through hundreds of thousands of dollars hiring outside counsel. -

Pluralism in Peril: Challenges to an American Ideal

PLURALISM IN PERIL: CHALLENGES TO AN AMERICAN IDEAL IDEAL AMERICAN AN TO CHALLENGES PERIL: IN PLURALISM PLURALISM IN PERIL: CHALLENGES TO AN AMERICAN IDEAL Report of the Inclusive America Project Report of the Inclusive America Project the Report Inclusive of January 2018 • Washington, D.C. Steven D. Martin – National Council of Churches THE ASPEN INSTITUTE JUSTICE AND SOCIETY PROGRAM 11-024 PLURALISM IN PERIL: CHALLENGES TO AN AMERICAN IDEAL Report of the Inclusive America Project January 2018 • Washington, D.C. Meryl Justin Chertoff Executive Editor Allison K. Ralph Editor The ideas and recommendations contained in this report should not be taken as representing the views or carrying the endorsement of the organization with which the author is affiliated. The organizations cited as examples in this report do not necessarily endorse the Inclusive America Project or its aims. For all inquiries related to the Inclusive America Project, please contact: Zeenat Rahman Project Director, Inclusive America Project [email protected] Copyright © 2018 by The Aspen Institute The Aspen Institute 2300 N Street, NW Suite 700 Washington, DC 20037 Published in the United States of America in 2018 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 18/001 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ..............................................v Executive Editor’s Note .........................................vii Letter to the Reader . ix Introduction ...................................................1 PART 1: EMERGING -

An Analysis of Ms. Marvel's Kamala Khan

The “Worlding” of the Muslim Superheroine: An Analysis of Ms. Marvel’s Kamala Khan SAFIYYA HOSEIN Muslim women have been a source of speculation for Western audiences from time immemorial. At first eroticized in harem paintings, they later became the quintessential image of subservience: a weakling to be pitied and rescued from savage Brown men. Current depictions of Muslim women have ranged from the oppressed archetype in mainstream media with films such as The Stoning of Soraya M (2008) to comedic veiled characters in shows like Little Mosque on the Prairie (2012). One segment of media that has recently offered promising attempts for destabilizing their image has been comics and graphic novels which have published graphic memoirs that speak to the complexity of Muslim identity as well as superhero comics that offer a range of Muslim characters from a variety of cultures with different levels of religiosity. This paper explores the emergence of the Muslim superheroine in comic books by analyzing the most developed Muslimah (Muslim female) superhero: the rebooted Ms. Marvel superhero, Kamala Khan, from the Marvel Comics Ms. Marvel series. The analysis illustrates how the reconfiguration of the Muslim female archetype through the “worlding” of the Muslim superhero continues to perpetuate an imperialist agenda for the Third World. This paper uses Gayatri Spivak’s “worlding” which examines the “othered” natives and the global South as defined through Eurocentric terms by imperialists and colonizers. By interrogating Kamala’s representation, I argue that her portrayal as a “moderate” Muslim superheroine with Western progressive values can have the effect of reinforcing Safiyya Hosein is a Ph.D. -

“The Once and Future Juggernaut”

WITH THE RECENT DEATHS OF CHARLES XAVIER AND WOLVERINE, THE JEAN GREY SCHOOL FOR HIGHER LEARNING HAS BEEN LEFT IN CHAOS. THE X-MEN ARE SPLINTERED AND BROKEN, AND WITH THE FUTURE OF MUTANTKIND HANGING IN THE BALANCE, IDEOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES HAVE SET LIFELONG FRIENDS AGAINST EACH OTHER. IN THE WAKE OF THIS SCHISM, MANY OF THE X-MEN HAVE FOUND THEMSELVES LOST AND SEARCHING FOR PURPOSE. ONE OF THESE X-MEN IS PIOTR RASPUTIN, KNOWN AS COLOSSUS, A MAN WHOSE HAS BEEN LEFT SCARRED BY THE HORRORS IN HIS PAST. HE HAS SEEN HIS FAMILY TORN APART, EVEN HAVING HIS SISTER CAPTURED BY THE DEMON BELASCO AND INFECTED BY THE DARK MAGIC OF HIS REALM OF LIMBO. HE WATCHED AS THE WOMEN HE LOVED WERE KIDNAPPED, LOST, AND KILLED. HE HAS DIED AND BEEN RESURRECTED. AND HIS MIND POSSESSED AND PERVERTED BY BEINGS SUCH AS THE PHOENIX AND CYTTORAK. A MAN WHO ONCE STOOD AS A SHINING, METAL EXAMPLE OF GOOD HAS SEEN HIS SOUL TAINTED BY HIS CHOICES AND THE BLOOD OF THOSE HE HAS KILLED. DESPITE ALL THIS, HE WAS GIVEN A CHANCE AT REDEMPTION BY WOLVERINE, REJOINING THE X-MEN AT THE JEAN GREY SCHOOL. HOWEVER, FACING DOWN HIS DEMONS WILL TAKE MORE THAN JUST SOME FREE ROOM AND BOARD. “THE ONCE AND FUTURE JUGGERNAUT” PART ONE OF FOUR WRITER CHRISTOPHER YOST ARTIST JORGE FORNÉS COLORIST RACHELLE ROSENBERG LETTERER VC’S JOE CARAMAGNA COVER BY KRIS ANKA ASSISTANT EDITOR XANDER JAROWEY EDITOR MIKE MARTS EDITOR IN CHIEF AXEL ALONSO CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER JOE QUESADA PUBLISHER DAN BUCKLEY EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALAN FINE X-MEN CREATED BY STAN LEE AND JACK KIRBY AMAZING X-MEN No. -

Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 Free Ebook

FREEMS. MARVEL: VOL. 2 EBOOK Adrian Alphona,Takeshi Miyazawa,G. Willow Wilson | 240 pages | 19 Apr 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785198369 | English | New York, United States Ms Marvel (Vol 2) #8 VF 1st Print Marvel Comics | eBay Marvel is the name of several fictional superheroes appearing in comic books published by Marvel Comics. The character was originally conceived as a female counterpart to Captain Marvel. Like Captain Marvel, most of the bearers of the Ms. Marvel title gain their powers through Kree technology or genetics. Marvel has published four ongoing comic series titled Ms. Marvelwith the first two starring Carol Danvers and the third and fourth starring Kamala Khan. Carol Danvers, the first character to use the moniker Ms. Marvel 1 January with super powers as result of the Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 which caused her DNA Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 merge with Captain Marvel's. As Ms. Danvers goes on to use the codenames Binary [1] and Warbird. Sharon Ventura, the second character to use the pseudonym Ms. Ventura later joins the Fantastic Four herself in Fantastic Four October and, after being hit by cosmic rays in Fantastic Four JanuaryVentura's body mutates into a similar appearance to that of The Thing and receives the nickname She-Thing. Sofen tricks Bloch into giving her the meteorite that empowers him, and she adopts both the Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 and abilities of Moonstone. Marvel, Carol Danvers, receiving a costume similar to Danvers' original Danvers wore the Warbird costume at the time. Marvel series beginning in issue 38 June until Danvers takes the title back in issue 47 January Kamala Khan, created by Sana AmanatG. -

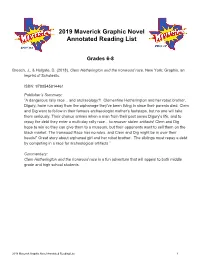

2019 Maverick Graphic Novel Annotated Reading List

2019 Maverick Graphic Novel Annotated Reading List Grades 6-8 Breach, J., & Holgate, D. (2018). Clem Hetherington and the Ironwood race. New York: Graphix, an imprint of Scholastic. ISBN: 9780545814461 Publisher’s Summary: “A dangerous rally race... and archaeology?! Clementine Hetherington and her robot brother, Digory, have run away from the orphanage they've been living in since their parents died. Clem and Dig want to follow in their famous archaeologist mother's footsteps, but no one will take them seriously. Their chance arrives when a man from their past saves Digory's life, and to repay the debt they enter a multi-day rally race... to recover stolen artifacts! Clem and Dig hope to win so they can give them to a museum, but their opponents want to sell them on the black market. The Ironwood Race has no rules, and Clem and Dig might be in over their heads!” Great story about orphaned girl and her robot brother. The siblings must repay a debt by competing in a race for archeological artifacts.” Commentary: Clem Hetherington and the Ironwood race is a fun adventure that will appeal to both middle grade and high school students. 2018 Maverick Graphic Novel Annotated Reading List 1 Brosgol, V. B. (2018). Be Prepared. Place of publication not identified: First Second. ISBN: 9781626724457 Publisher’s Summary: "In Be Prepared, all Vera wants to do is fit in—but that’s not easy for a Russian girl in the suburbs. Her friends live in fancy houses and their parents can afford to send them to the best summer camps. -

Her Own Heroine: Feminism and Diversity in the Comic Book Industry

Panel Title: Her Own Heroine: Feminism and Diversity in the Comic Book Industry Moderator: Patricia B. Worrall, Ph.D. English Department University of North Georgia [email protected] First Speaker: Veronica Harris English Department University of North Georgia [email protected] Title: “Breaking the Mold: Ororo Munroe and the Entertainment Industry” Proposal: Throughout the history and development of comic books, there has been adaptations of the characters to different media venues. Storm, or Ororo Munroe, is no exception. She comes from the African country of Kenya born to a native woman and American man. Her mother comes from a line of priestesses said to hold mystical powers to protect their tribes. At a young age, she experiences a tragic plane crashing into her home, which traps her under her mother’s body and rubble. She develops claustrophobic tendencies, which awaken her powers. Later in life, she comes to teach at the Xavier School for Gifted Youngsters, i.e. mutants, and becomes one of the most powerful X-Men. Representations of Storm occur in many different forms of visual media, such as movies and comics. However, the medium of film limits the development of her backstory and heritage because of the film industry’s shift to an emphasis and focus on white males taken from comics. This shift has resulted in restricting and restraining women of color. On the other hand, cartoons, such as Wolverine and the X-Men and X-Men Evolution , do provide some space for her. Although even in comic space restricts and restrains women of color and becomes analogous to Storm’s claustrophobia. -

Whitewashing Or Amnesia: a Study of the Construction

WHITEWASHING OR AMNESIA: A STUDY OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE IN TWO MIDWESTERN COUNTIES A DISSERTATION IN Sociology and History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by DEBRA KAY TAYLOR M.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2005 B.L.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2000 Kansas City, Missouri 2019 © 2019 DEBRA KAY TAYLOR ALL RIGHTS RESERVE WHITEWASHING OR AMNESIA: A STUDY OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF RACE IN TWO MIDWESTERN COUNTIES Debra Kay Taylor, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2019 ABSTRACT This inter-disciplinary dissertation utilizes sociological and historical research methods for a critical comparative analysis of the material culture as reproduced through murals and monuments located in two counties in Missouri, Bates County and Cass County. Employing Critical Race Theory as the theoretical framework, each counties’ analysis results are examined. The concepts of race, systemic racism, White privilege and interest-convergence are used to assess both counties continuance of sustaining a racially imbalanced historical narrative. I posit that the construction of history of Bates County and Cass County continues to influence and reinforces systemic racism in the local narrative. Keywords: critical race theory, race, racism, social construction of reality, white privilege, normality, interest-convergence iii APPROVAL PAGE The faculty listed below, appointed by the Dean of the School of Graduate Studies, have examined a dissertation titled, “Whitewashing or Amnesia: A Study of the Construction of Race in Two Midwestern Counties,” presented by Debra Kay Taylor, candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, and certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance.