Internal Aspects of Flute Technique: a Mixed-Method

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commissioned Flute Choir Pieces Presented By

THE COMMISSIONED FLUTE CHOIR PIECES PRESENTED BY UNIVERSITY/COLLEGE FLUTE CHOIRS AND NFA SPONSORED FLUTE CHOIRS AT NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION ANNUAL CONVENTIONS WITH A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FLUTE CHOIR AND ITS REPERTOIRE DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yoon Hee Kim Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Russel C. Mikkelson Dr. Charles M. Atkinson Karen Pierson Copyright by Yoon Hee Kim 2013 Abstract The National Flute Association (NFA) sponsors a range of non-performance and performance competitions for performers of all ages. Non-performance competitions are: a Flute Choir Composition Competition, Graduate Research, and Newly Published Music. Performance competitions are: Young Artist Competition, High School Soloist Competition, Convention Performers Competition, Flute Choirs Competitions, Professional, Collegiate, High School, and Jazz Flute Big Band, and a Masterclass Competition. These competitions provide opportunities for flutists ranging from amateurs to professionals. University/college flute choirs perform original manuscripts, arrangements and transcriptions, as well as the commissioned pieces, frequently at conventions, thus expanding substantially the repertoire for flute choir. The purpose of my work is to document commissioned repertoire for flute choir, music for five or more flutes, presented by university/college flute choirs and NFA sponsored flute choirs at NFA annual conventions. Composer, title, premiere and publication information, conductor, performer and instrumentation will be included in an annotated bibliography format. A brief history of the flute choir and its repertoire, as well as a history of NFA-sponsored flute choir (1973–2012) will be included in this document. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

Composers' Bridge!

Composers’ Bridge Workbook Contents Notation Orchestration Graphic notation 4 Orchestral families 43 My graphic notation 8 Winds 45 Clefs 9 Brass 50 Percussion 53 Note lengths Strings 54 Musical equations 10 String instrument special techniques 59 Rhythm Voice: text setting 61 My rhythm 12 Voice: timbre 67 Rhythmic dictation 13 Tips for writing for voice 68 Record a rhythm and notate it 15 Ideas for instruments 70 Rhythm salad 16 Discovering instruments Rhythm fun 17 from around the world 71 Pitch Articulation and dynamics Pitch-shape game 19 Articulation 72 Name the pitches – part one 20 Dynamics 73 Name the pitches – part two 21 Score reading Accidentals Muddling through your music 74 Piano key activity 22 Accidental practice 24 Making scores and parts Enharmonics 25 The score 78 Parts 78 Intervals Common notational errors Fantasy intervals 26 and how to catch them 79 Natural half steps 27 Program notes 80 Interval number 28 Score template 82 Interval quality 29 Interval quality identification 30 Form Interval quality practice 32 Form analysis 84 Melody Rehearsal and concert My melody 33 Presenting your music in front Emotion melodies 34 of an audience 85 Listening to melodies 36 Working with performers 87 Variation and development Using the computer Things you can do with a Computer notation: Noteflight 89 musical idea 37 Sound exploration Harmony My favorite sounds 92 Harmony basics 39 Music in words and sentences 93 Ear fantasy 40 Word painting 95 Found sound improvisation 96 Counterpoint Found sound composition 97 This way and that 41 Listening journal 98 Chord game 42 Glossary 99 Welcome Dear Student and family Welcome to the Composers' Bridge! The fact that you are being given this book means that we already value you as a composer and a creative artist-in-training. -

Slap Tongue (Saxophone Pizzicato)

Excerpt from “Part IV: Extended Techniques for Saxophone” Writing for Saxophones: A Guide to the Tonal Palette of the Saxophone Family for Composers, Arrangers and Performers by Jay C. Easton, D.M.A. (for further excerpts and ordering information, please visit http://baxtermusicpublishing.com) • Slap Tongue (saxophone pizzicato) Slap tongue is a versatile and interesting effect that is available in four varieties: 1. “melodic” slap or pizzicato (clearly pitched): melodic “plucking” sound entire keyed range of horn (but not altissimo) Maximum tempo: 240 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 2. “slap tone” (clearly pitched): melodic slap attack followed by normal tone Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 3. “woodblock” slap (unpitched): soft, dry percussive sound Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to mf dynamics 4. “explosive” slap or “open” slap (unpitched): loud percussive sound Maximum tempo: 70 beats per minute Possible from mf to ff dynamics Not all saxophonists know how to slap tongue but an increasing number are learning the technique. The “melodic” slap and “slap tone” are produced by holding the tongue against about 1/3 to 1/2 of the tip end of the reed surface – a centimeter or so – and creating a suction-cup effect between tongue and reed. This is accomplished by pulling the middle of the tongue slightly away from the reed while keeping the edges and tip of the tongue sealed tight against it. The tongue is then quickly released by pushing it forward and downward away from the reed, creating suction between the tongue and the reed; this tongue motion is accompanied by sudden slight impulse of air. -

Teaching Rhythm: a Comparative Study of Beginning Band and Solo Flute Method Books

MITCHELL, AMANDA K., D.M.A. Teaching Rhythm: A Comparative Study of Beginning Band and Solo Flute Method Books. (2017) Directed by Dr. Michael Burns. 44 pp. Typically, teachers of private instrumental lessons and large ensembles rely on a method book to supplement instruction regarding the fundamentals of music. The method books chosen by these instructors differ due to the nature of the teaching environments. Numerous books have been written specifically for the varied structure of these learning environments, to address various philosophies and approaches. This led to the development of method books specifically used in either private lessons or large ensemble settings. One of the most integral elements of music found in these method books is rhythm. The purpose of this study is to present comparative data related to the content and sequencing of rhythmic instruction in beginning flute method books for both private lesson and large ensemble environments. Four books intended for each instructional setting were used to provide the data for this study. The comprehensive band method books analyzed were Essential Elements for Band,1 Tradition of Excellence,2 Sound Innovations,3 and Measure of Success.4 The solo flute methods analyzed were; 1 Tim Lautzenheiser et al., Essential Elements for Band: Comprehensive Band Method (Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2004). 2 Bruce Pearson and Ryan Nowlin, Tradition of Excellence: Comprehensive Band Method (San Diego: Kjos Music Press, 2010). 3 Robert Sheldon et al., Sound Innovations for Concert Band: A Revolutionary Method for Beginning Musicians (New York: Alfred Music Publishing Co., Inc., 2010). 4 Deborah A. Sheldon et al., Measures of Success: A Comprehensive Band Method. -

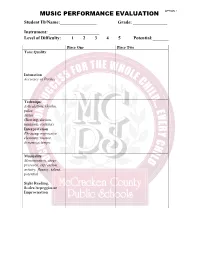

Music Performance Evaluation

OPTION 1 Student ID/Name:________________ Grade: _______________ Instrument: ______________________ Level of Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5 Potential:_______ Piece One Piece Two Tone Quality Intonation Accuracy of Pitches Technique Articulation, rhythm, pulse, Meter (Bowing, diction, tonguing, sticking) Interpretation Phrasing, expressive elements, nuance, dynamics, tempo Musicality Memorization, stage presence, expression, artistry, fluency, talent, potential Sight Reading, Scales/Arpeggios or Improvisation OPTION 1 Distinguished Proficient Apprentice Novice Tone Quality Tone is warm, resonant, Tone has some Tone has apparent Tone is weak, controlled, clear, focused, warmth, resonance inconsistencies breathy, forced consistent, vibrant, rich, and clarity, with with some or unclear. full, beautiful. some resonance and inconsistencies. clarity. Intonation Printed pitches are Some inaccurate Several inaccurate Inaccurate Accuracy of performed with accuracy; pitches and some pitches and pitches; out of intonation is within the intonation problems. difficulty tune. Pitches appropriate range. Student playing/singing in shifts cleanly. tune consistently. Technique Student used appropriate Enough technical Some technical Flawed Articulation, technique, as printed or flaws to detract from flaws. Not technique. indicated stylistically for performance. Style stylistically Inaccurate rhythm, pulse, the selection. Attacks and somewhat appropriate. rhythms, time Meter releases are clear. Slurs appropriate. Some Printed signature not (Bowing, diction, are smooth and connected. inconsistencies in articulations not followed, tonguing, Pulse of the music is performance or followed accents sticking, steady. Indicated meter is printed articulations. accurately. overdone or not performed correctly. Some unsteadiness Unsteady pulse. apparent. Slurs fingering) Notes and rests are held for of pulse. Some Several rhythmic are unclear. the correct value. rhythmic errors. errors. Technique is not appropriate stylistically. -

The Influence of Tonguing on Tone Production With

5th Congress of Alps-Adria Acoustics Association 12-14 September 2012, Petrþane, Croatia __________________________________________________________________________________________ !"#$% #' !($!(#) "#)!(#!(# !*+(, '"(#!-"! ."#)% /+ ,!-((,-"#,!"#.+ 0 #. Alex Hofmann,*¹ Vasileios Chatziioannou,* Wilfried Kausel,* Werner Goebl,* Michael Weilguni,# Walter Smetana # *Institute of Music Acoustics, University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, Austria #Institute of Sensor and Actuator Systems, Vienna University of Technology, Austria ¹[email protected] Abstract: Physical modelling based sound-synthesis requires physically meaningful parameters for controlling the model. Previous studies on modelling single-reed woodwind instruments have concentrated mostly on the influence of the pressure difference across the reed on the behavior of the reed oscillation. The interaction with the player's lips and the mouthpiece lay has also been taken into account. However, studies on the effect of the player's tongue are limited. Articulation on real saxophones is produced by tongue impulses to the reed. In portato playing the air pressure is held approximately constant by the player, while there are articular interactions of the tongue with the reed. In this study we aim to explain the influence of tonguing for tone production with single-reed woodwind instruments using experimental measurements in an attempt to model articulation in sound synthesis. During the experiments an alto-saxophone mouthpiece was attached to the saxophone neck and tones with different articulation were recorded. The mouthpiece pressure was measured using a microphone inserted into the mouthpiece and a strain gauge glued on a synthetic reed was used to track the reed bending. A damping effect of the tongue on the oscillating reed can be observed between two articulated tones and the release of the tongue affects the transient behavior of the instrument. -

Extended Techniques in Stanley Friedman's

EXTENDED TECHNIQUES IN STANLEY FRIEDMAN'S SOLUS FOR UNACCOMPANIED TRUMPET Scott Meredith, B.M., B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Keith Johnson, Major Professor Lenora McCroskey, Minor Professor John Holt, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Meredith, Scott. Extended Techniques in Stanley Friedman’s Solus for Unaccompanied Trumpet. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2008, 37 pp., 25 examples, 3 tables, bibliography, 23 titles. This document examines the technical execution of extended techniques incorporated in the musical structure of Solus, and explores the benefits of introducing the work into the curriculum of a college level trumpet studio. Compositional style, form, technical accessibility, and pedagogical benefits are investigated in each of the four movements. An interview with the composer forms the foundation for the history of the composition as well as the genesis of some of the extended techniques and programmatic ideas. Copyright 2008 by Scott Meredith ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My deepest thanks go to Keith Johnson for his mentorship, guidance, and friendship. He has been instrumental in my development as a player, teacher, and citizen. I owe a great amount of gratitude to my colleagues John Wacker and Robert Murray for their continued support, encouragement, friendship, and belief in my dream. I owe a debt of gratitude to Lenora McCroskey for her knowledge of all things music and her willingness to drop everything for her students. -

Paired Syllables and Unequal Tonguing Patterns on Woodwinds in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Bruce Haynes

Performance Practice Review Volume 10 Article 5 Number 1 Spring Tu ru or not Tu ru: Paired Syllables and Unequal Tonguing Patterns on Woodwinds in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Bruce Haynes Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Haynes, Bruce (1997) "Tu ru or not Tu ru: Paired Syllables and Unequal Tonguing Patterns on Woodwinds in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 10: No. 1, Article 5. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199710.01.05 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol10/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 42 Bruce Haynes -> - As Hotteterre wrote, On observera seulement de ne point You must only observe never t prononcer Ru sur l& Tremblements; ni pronounce Ru on a shake, nor on sur deux Notes de suite, parceque le Ru two successive Notes, because Ru doit toujours &re m216 alternativement ought always to be intermixt alter- avec le TU.~ natively with TU' The R works when preceded by T,however (as in t dah). Quantz writes: I1 faut s'appliquer 2 prononcer trh fortement & distinctement la lettre r. sharply and clearly. It produces Cela fait 2 l'oreille le meme effet que the same effect on the ear as the lors qu'on se sen de di, en jouant de single-tongue di, although it does la simple langue: quoic)ue il ne not seem so to the player. -

The Art of Marimba Articulation: a Guide for Composers, Conductors, And

THE ART OF MARIMBA ARTICULATION: A GUIDE FOR COMPOSERS, CONDUCTORS, AND PERFORMERS ON THE EXPRESSIVE CAPABILITIES OF THE MARIMBA Adam B. Davis, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2018 APPROVED: Mark Ford, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member Christopher Deane, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies Musicin the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School The Art of Marimba Articulation: A Guide for Composers, Conductors, and PerformersDavis, Adam on the B. Expressive Capabilities of the Marimba 233 6 . Doctor of Musical82 titles. Arts (Performance), August 2018, pp., tables, 49 figures, bibliography, Articulation is an element of musical performance that affects the attack, sustain, and the decay of each sound. Musical articulation facilitates the degree of clarity between successive notes and it is one of the most important elements of musical expression. Many believe that the expressive capabilities of percussion instruments, when it comes to musical articulation, are limited. Because the characteristic attack for most percussion instruments is sharp and clear, followed by a quick decay, the common misconception is that percussionists have little or no control over articulation. While the ability of percussionists to affect the sustain and decay of a sound is by all accounts limited, the virtuability of percussionists to change the attack of a sound with different implements is ally limitless. In addition, where percussion articulation is limited, there are many techniques that allow performers to match articulation with other instruments. -

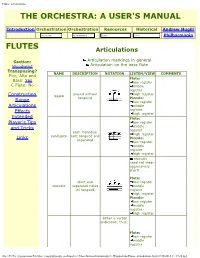

Flutes: Articulations the ORCHESTRA: a USER's MANUAL

Flutes: articulations THE ORCHESTRA: A USER'S MANUAL Introduction Orchestration Orchestration Resources Historical Andrew Hugill by section by instrument select... select... Philharmonia FLUTES Articulations Section: Articulation markings in general Woodwind Articulation on the bass flute Transposing? NAME DESCRIPTION NOTATION LISTEN/VIEW COMMENTS Picc, Alto and Flute: Bass: Yes low register C Flute: No middle register played without high register Construction legato tonguing Piccolo: Range low register Articulations middle Effects register high register Extended Flute: Player's Tips low register middle and Tricks register each individual high register nonlegato note tongued and Links Piccolo: separated low register middle register high register staccato need not mean aggressively short! Flute: short and low register staccato separated notes middle (all tongued) register high register Piccolo: low register middle register high register Either a verbal indication, thus: Flute: low register middle register file:///E|/Τα έγγραφά μου/Τσέτσος, ενορχήστρωση (μαθήματα)+/Enorchistrosi Instruments/3. Woodwinds/Flutes articulations.htm[17/10/2015 11:17:28 πμ] Flutes: articulations high register very short notes staccatissimo Piccolo: (tongued) or 'wedge' low register notation, as middle follows: register high register tongued slurring interpretation depending on context Players interpret tongued slurred Flute: these symbols in (no specific notes, in low register different ways. name) between legato middle Watch the video and nonlegato register clips for a brief high register explanation. Piccolo: low register middle register high register This is often called 'tenuto': Flute: low register middle register high register variation on Here's another 'tenuto' Piccolo: nonlegato common low register variation of middle nonlegato: register high register double tonguing Flute: low register middle register double tonguing high register Piccolo: low register file:///E|/Τα έγγραφά μου/Τσέτσος, ενορχήστρωση (μαθήματα)+/Enorchistrosi Instruments/3. -

Pointers for New Flute Teachers

ALL FLUTE TEACHING ARTICLES COLLECTED FROM FLUTENET General flute teaching information for printing out; use double siding for 25 pages Pointers for new flute teachers: How much to charge? Charge only 1/3 to ½ of what your own flute teacher charges. For example, if your teacher charges $45 an hour, you should ask for $20/hr. or less as a fee while working under your mentor. If your teacher charges $30 an hour, you should charge about $12. Until the time comes when you receive teacher’s certification, an A.R.C.T. (Royal Conservatory Associateship) or a Bachelor’s degree in music, you cannot charge more than half of what a highly qualified teacher charges. After you have taught 5-10 years, you can gradually charge more. Please consult with your own teacher about acceptable prices for private lessons, and be sure and keep abreast of all the latest flute teaching news. ------------------------------------------------------------------ More pointers………. 1. Make sure you are taking flute lessons yourself and using your own teacher as a mentor. You can’t teach what you don’t know. Please please don’t create bad-habits in flute youngsters by showing them mis-learned concepts. Bad habits on flute and flute-myths are discussed at: http://www.jennifercluff.com/habits.htm and at http://www.jennifercluff.com/myths.htm 2. Take your own flute teaching issues to your own teacher and have “hands on” lessons on how to demonstrate flute playing for students. Examples: how to put the instrument together without bending the keys or rods, how to learn to blow on the headjoint only; how to read a fingering chart; how to teach a child how to read music etc.