Paired Syllables and Unequal Tonguing Patterns on Woodwinds in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Bruce Haynes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Composers' Bridge!

Composers’ Bridge Workbook Contents Notation Orchestration Graphic notation 4 Orchestral families 43 My graphic notation 8 Winds 45 Clefs 9 Brass 50 Percussion 53 Note lengths Strings 54 Musical equations 10 String instrument special techniques 59 Rhythm Voice: text setting 61 My rhythm 12 Voice: timbre 67 Rhythmic dictation 13 Tips for writing for voice 68 Record a rhythm and notate it 15 Ideas for instruments 70 Rhythm salad 16 Discovering instruments Rhythm fun 17 from around the world 71 Pitch Articulation and dynamics Pitch-shape game 19 Articulation 72 Name the pitches – part one 20 Dynamics 73 Name the pitches – part two 21 Score reading Accidentals Muddling through your music 74 Piano key activity 22 Accidental practice 24 Making scores and parts Enharmonics 25 The score 78 Parts 78 Intervals Common notational errors Fantasy intervals 26 and how to catch them 79 Natural half steps 27 Program notes 80 Interval number 28 Score template 82 Interval quality 29 Interval quality identification 30 Form Interval quality practice 32 Form analysis 84 Melody Rehearsal and concert My melody 33 Presenting your music in front Emotion melodies 34 of an audience 85 Listening to melodies 36 Working with performers 87 Variation and development Using the computer Things you can do with a Computer notation: Noteflight 89 musical idea 37 Sound exploration Harmony My favorite sounds 92 Harmony basics 39 Music in words and sentences 93 Ear fantasy 40 Word painting 95 Found sound improvisation 96 Counterpoint Found sound composition 97 This way and that 41 Listening journal 98 Chord game 42 Glossary 99 Welcome Dear Student and family Welcome to the Composers' Bridge! The fact that you are being given this book means that we already value you as a composer and a creative artist-in-training. -

Slap Tongue (Saxophone Pizzicato)

Excerpt from “Part IV: Extended Techniques for Saxophone” Writing for Saxophones: A Guide to the Tonal Palette of the Saxophone Family for Composers, Arrangers and Performers by Jay C. Easton, D.M.A. (for further excerpts and ordering information, please visit http://baxtermusicpublishing.com) • Slap Tongue (saxophone pizzicato) Slap tongue is a versatile and interesting effect that is available in four varieties: 1. “melodic” slap or pizzicato (clearly pitched): melodic “plucking” sound entire keyed range of horn (but not altissimo) Maximum tempo: 240 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 2. “slap tone” (clearly pitched): melodic slap attack followed by normal tone Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 3. “woodblock” slap (unpitched): soft, dry percussive sound Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to mf dynamics 4. “explosive” slap or “open” slap (unpitched): loud percussive sound Maximum tempo: 70 beats per minute Possible from mf to ff dynamics Not all saxophonists know how to slap tongue but an increasing number are learning the technique. The “melodic” slap and “slap tone” are produced by holding the tongue against about 1/3 to 1/2 of the tip end of the reed surface – a centimeter or so – and creating a suction-cup effect between tongue and reed. This is accomplished by pulling the middle of the tongue slightly away from the reed while keeping the edges and tip of the tongue sealed tight against it. The tongue is then quickly released by pushing it forward and downward away from the reed, creating suction between the tongue and the reed; this tongue motion is accompanied by sudden slight impulse of air. -

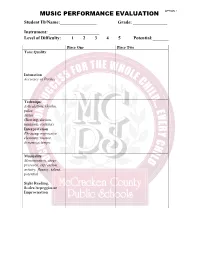

Music Performance Evaluation

OPTION 1 Student ID/Name:________________ Grade: _______________ Instrument: ______________________ Level of Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5 Potential:_______ Piece One Piece Two Tone Quality Intonation Accuracy of Pitches Technique Articulation, rhythm, pulse, Meter (Bowing, diction, tonguing, sticking) Interpretation Phrasing, expressive elements, nuance, dynamics, tempo Musicality Memorization, stage presence, expression, artistry, fluency, talent, potential Sight Reading, Scales/Arpeggios or Improvisation OPTION 1 Distinguished Proficient Apprentice Novice Tone Quality Tone is warm, resonant, Tone has some Tone has apparent Tone is weak, controlled, clear, focused, warmth, resonance inconsistencies breathy, forced consistent, vibrant, rich, and clarity, with with some or unclear. full, beautiful. some resonance and inconsistencies. clarity. Intonation Printed pitches are Some inaccurate Several inaccurate Inaccurate Accuracy of performed with accuracy; pitches and some pitches and pitches; out of intonation is within the intonation problems. difficulty tune. Pitches appropriate range. Student playing/singing in shifts cleanly. tune consistently. Technique Student used appropriate Enough technical Some technical Flawed Articulation, technique, as printed or flaws to detract from flaws. Not technique. indicated stylistically for performance. Style stylistically Inaccurate rhythm, pulse, the selection. Attacks and somewhat appropriate. rhythms, time Meter releases are clear. Slurs appropriate. Some Printed signature not (Bowing, diction, are smooth and connected. inconsistencies in articulations not followed, tonguing, Pulse of the music is performance or followed accents sticking, steady. Indicated meter is printed articulations. accurately. overdone or not performed correctly. Some unsteadiness Unsteady pulse. apparent. Slurs fingering) Notes and rests are held for of pulse. Some Several rhythmic are unclear. the correct value. rhythmic errors. errors. Technique is not appropriate stylistically. -

The Influence of Tonguing on Tone Production With

5th Congress of Alps-Adria Acoustics Association 12-14 September 2012, Petrþane, Croatia __________________________________________________________________________________________ !"#$% #' !($!(#) "#)!(#!(# !*+(, '"(#!-"! ."#)% /+ ,!-((,-"#,!"#.+ 0 #. Alex Hofmann,*¹ Vasileios Chatziioannou,* Wilfried Kausel,* Werner Goebl,* Michael Weilguni,# Walter Smetana # *Institute of Music Acoustics, University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, Austria #Institute of Sensor and Actuator Systems, Vienna University of Technology, Austria ¹[email protected] Abstract: Physical modelling based sound-synthesis requires physically meaningful parameters for controlling the model. Previous studies on modelling single-reed woodwind instruments have concentrated mostly on the influence of the pressure difference across the reed on the behavior of the reed oscillation. The interaction with the player's lips and the mouthpiece lay has also been taken into account. However, studies on the effect of the player's tongue are limited. Articulation on real saxophones is produced by tongue impulses to the reed. In portato playing the air pressure is held approximately constant by the player, while there are articular interactions of the tongue with the reed. In this study we aim to explain the influence of tonguing for tone production with single-reed woodwind instruments using experimental measurements in an attempt to model articulation in sound synthesis. During the experiments an alto-saxophone mouthpiece was attached to the saxophone neck and tones with different articulation were recorded. The mouthpiece pressure was measured using a microphone inserted into the mouthpiece and a strain gauge glued on a synthetic reed was used to track the reed bending. A damping effect of the tongue on the oscillating reed can be observed between two articulated tones and the release of the tongue affects the transient behavior of the instrument. -

Extended Techniques in Stanley Friedman's

EXTENDED TECHNIQUES IN STANLEY FRIEDMAN'S SOLUS FOR UNACCOMPANIED TRUMPET Scott Meredith, B.M., B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Keith Johnson, Major Professor Lenora McCroskey, Minor Professor John Holt, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Meredith, Scott. Extended Techniques in Stanley Friedman’s Solus for Unaccompanied Trumpet. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2008, 37 pp., 25 examples, 3 tables, bibliography, 23 titles. This document examines the technical execution of extended techniques incorporated in the musical structure of Solus, and explores the benefits of introducing the work into the curriculum of a college level trumpet studio. Compositional style, form, technical accessibility, and pedagogical benefits are investigated in each of the four movements. An interview with the composer forms the foundation for the history of the composition as well as the genesis of some of the extended techniques and programmatic ideas. Copyright 2008 by Scott Meredith ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My deepest thanks go to Keith Johnson for his mentorship, guidance, and friendship. He has been instrumental in my development as a player, teacher, and citizen. I owe a great amount of gratitude to my colleagues John Wacker and Robert Murray for their continued support, encouragement, friendship, and belief in my dream. I owe a debt of gratitude to Lenora McCroskey for her knowledge of all things music and her willingness to drop everything for her students. -

The Art of Marimba Articulation: a Guide for Composers, Conductors, And

THE ART OF MARIMBA ARTICULATION: A GUIDE FOR COMPOSERS, CONDUCTORS, AND PERFORMERS ON THE EXPRESSIVE CAPABILITIES OF THE MARIMBA Adam B. Davis, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2018 APPROVED: Mark Ford, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member Christopher Deane, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies Musicin the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School The Art of Marimba Articulation: A Guide for Composers, Conductors, and PerformersDavis, Adam on the B. Expressive Capabilities of the Marimba 233 6 . Doctor of Musical82 titles. Arts (Performance), August 2018, pp., tables, 49 figures, bibliography, Articulation is an element of musical performance that affects the attack, sustain, and the decay of each sound. Musical articulation facilitates the degree of clarity between successive notes and it is one of the most important elements of musical expression. Many believe that the expressive capabilities of percussion instruments, when it comes to musical articulation, are limited. Because the characteristic attack for most percussion instruments is sharp and clear, followed by a quick decay, the common misconception is that percussionists have little or no control over articulation. While the ability of percussionists to affect the sustain and decay of a sound is by all accounts limited, the virtuability of percussionists to change the attack of a sound with different implements is ally limitless. In addition, where percussion articulation is limited, there are many techniques that allow performers to match articulation with other instruments. -

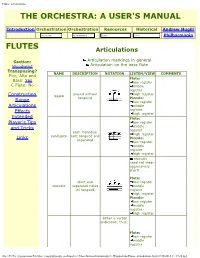

Flutes: Articulations the ORCHESTRA: a USER's MANUAL

Flutes: articulations THE ORCHESTRA: A USER'S MANUAL Introduction Orchestration Orchestration Resources Historical Andrew Hugill by section by instrument select... select... Philharmonia FLUTES Articulations Section: Articulation markings in general Woodwind Articulation on the bass flute Transposing? NAME DESCRIPTION NOTATION LISTEN/VIEW COMMENTS Picc, Alto and Flute: Bass: Yes low register C Flute: No middle register played without high register Construction legato tonguing Piccolo: Range low register Articulations middle Effects register high register Extended Flute: Player's Tips low register middle and Tricks register each individual high register nonlegato note tongued and Links Piccolo: separated low register middle register high register staccato need not mean aggressively short! Flute: short and low register staccato separated notes middle (all tongued) register high register Piccolo: low register middle register high register Either a verbal indication, thus: Flute: low register middle register file:///E|/Τα έγγραφά μου/Τσέτσος, ενορχήστρωση (μαθήματα)+/Enorchistrosi Instruments/3. Woodwinds/Flutes articulations.htm[17/10/2015 11:17:28 πμ] Flutes: articulations high register very short notes staccatissimo Piccolo: (tongued) or 'wedge' low register notation, as middle follows: register high register tongued slurring interpretation depending on context Players interpret tongued slurred Flute: these symbols in (no specific notes, in low register different ways. name) between legato middle Watch the video and nonlegato register clips for a brief high register explanation. Piccolo: low register middle register high register This is often called 'tenuto': Flute: low register middle register high register variation on Here's another 'tenuto' Piccolo: nonlegato common low register variation of middle nonlegato: register high register double tonguing Flute: low register middle register double tonguing high register Piccolo: low register file:///E|/Τα έγγραφά μου/Τσέτσος, ενορχήστρωση (μαθήματα)+/Enorchistrosi Instruments/3. -

Tonguing and Articulation METHOD BOOK LEVEL 1B

METHOD BOOK Lesson 2.4 – Tonguing and Articulation Every note that is played on a brass instrument has a beginning, middle and an end. What is happening at each of these moments? How are we starting and stopping the sound of each note? In this lesson, we will look at several articulation basics that help us play the notes in the right style. “Too” vs. “Doo” & “Toh” vs. “Doh” There are different approaches that can be taken when articulating or starting a note. Here are four different syllables to think about when playing. They are slightly different, but will become more noticeable as you advance. T – Starting with the T syllable should give a concise front to the note. D – Starting with the D syllable should give a smoother front to the note. “Too” vs. “Toh" – Playing “too” is considered the default approach for brass. It is a good way to blow air straight through the instrument and achieve a supported sound. However, “toh” is useful if you want to achieve a deeper sound. “Doo” vs. “Doh” – This concept is the same as “too” vs. “toh” except the front of the articulation is now softened by the D syllable. Short To play short, you use a quick “too” articulation with fast air. The air stream should be open and free, not stopped by the tongue or by closing off your throat. Imagine flicking an object with your finger. Accented To play an accented note, place a strong and well supported “too” at the front of the note. Think of your air stream as wide at the beginning before returning to normal. -

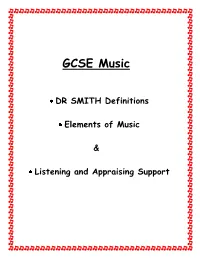

Elements of Music

GCSE Music DR SMITH Definitions Elements of Music & Listening and Appraising Support DR SMITH Definitions D Dynamics – Volume in music e.g. Loud (Forte) & Quiet (Piano). Duration – The length of notes, how many beats they last for. Link this to the time signature and how many beats in the bar. R Rhythm – The effect created by combining a variety of notes with different durations. Consider syncopation, cross rhythms, polyrhythm’s, duplets and triplets. S Structure – The overall plan of a piece of music e.g Ternary ABA and Rondo ABACAD, verse/chorus. M Melody – The effect created by combining a variety of notes of different pitches. Consider the movement e.g steps, skips, leaps. Metre – The number of beats in a bar e.g 3/4, 6/8 consider regular and irregular time signatures e.g. 4/4, 5/4. I Instrumentation – The combination of instruments that are used, consider articulation and timbre e.g staccato, legato, pizzicato. T Texture – The different layers in a piece of Music e.g polyphonic, monophonic, thick, thin. Tempo – The speed of the music e.g. fast (Allegro), Moderate (Andante), & slow (Lento / Largo). Timbre – The tone quality of the music, the different sound made by the instruments used. Tonality – The key of a piece of music e.g Major (happy), Minor (sad), atonal. H Harmony – How notes are combined to build up chords. Consider concords and discords. Elements of Music – Music Vocabulary Dynamics - Volume Fortissimo (ff) – Very loud Forte (f) – Loud Mezzo Forte (mf) – Moderately loud Mezzo Piano (mp) – Moderately quiet Piano (p) – Quiet Pianissimo (pp) – Very quiet Crescendo (Cresc.) - Gradually getting louder Diminuendo (Dim.) - Gradually getting quieter Subito/Fp – Loud then suddenly soft Dynamics - Listening Is the music loud or quiet? Are the changes sudden or gradual? Does the dynamic change often? Is there use of either a sudden loud section or note, or complete silence? Is the use of dynamics linked to the dramatic situation? If so, how does it enhance it? Duration/Rhythm (length of notes etc.) Note values e.g. -

INTRODUCTION to SINGLE and MULTIPLE ARTICULATION by Dr

INTRODUCTION TO SINGLE AND MULTIPLE ARTICULATION by Dr. Brian A. Shook I. Basic Concepts of Articulation a. The Air i. In order to properly execute articulation of any type, the airflow must be constant and consistent, producing a resonant tone ii. The airflow needs to be just like water coming out of a water faucet at a steady rate of speed b. The Tongue i. When single tonguing, always place “the tip of the tongue to the top of the teeth” 1. This is approximately where the gums and upper teeth meet when you say “Tee,” “Tah,” Toh,” “Dee,” “Dah,” or “Doh” 2. AVOID having the tongue strikes between the teeth and/or touching the lips, as if to say “The” or “Thee.” This will cause the buzz to stop and will result in a harsh start/stop articulation and buzz. ii. Continuing the water analogy from above, when you flick your finger through the steady stream of water coming out of the faucet, the water continues to flow regardless of how fast your finger passes through the stream—it does not slow down or speed up. This demonstrates exactly how your air should stay constant and consistent regardless of your articulation. iii. Remember, the tongue itself does not create any sound; it is merely a split- second interrupter of the air, giving shape and dimension to the sound. c. The Buzz i. Supplying the lips with steady airflow will ensure a vibrant buzz ii. Small amounts of free buzzing and mouthpiece buzzing (without articulation) will help improve your buzz quality d. -

How Clarinettists Articulate: the Effect of Blowing Pressure and Tonguing on Initial and Final Transients

How clarinettists articulate: The effect of blowing pressure and tonguing on initial and final transients Weicong Li,a) Andre Almeida, John Smith, and Joe Wolfe School of Physics, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, 2052, Australia (Received 20 July 2015; revised 18 January 2016; accepted 28 January 2016; published online 16 February 2016) Articulation, including initial and final note transients, is important to tasteful music performance. Clarinettists’ tongue-reed contact, the time variation of the blowing pressure Pmouth, the mouthpiece pressure, the pressure in the instrument bore, and the radiated sound were measured for normal articulation, accents, sforzando, staccato, and for minimal attack, i.e., notes started very softly. All attacks include a phase when the amplitude of the fundamental increases exponentially, with rates À1 r 1000 dB s controlled by varying both the rate of increase in Pmouth and the timing of tongue release during this increase. Accented and sforzando notes have shorter attacks (r1300 dB sÀ1) than normal notes. Pmouth reaches a higher peak value for accented and sforzando notes, followed by a steady decrease for accented notes or a rapid fall to a lower, nearly steady value for sforzando notes. Staccato notes are usually terminated by tongue contact, producing an exponential decrease in sound pressure with rates similar to those calculated from the bandwidths of the bore resonances: À1 400 dB s . In all other cases, notes are stopped by decreasing Pmouth. Notes played with different dynamics are qualitatively similar, but louder notes have larger Pmouth and larger r. VC 2016 Acoustical Society of America.[http://dx.doi.org/10.1121/1.4941660] [TRM] Pages: 825–838 I. -

Articulation Technique for Wind Instruments to Get What They Called “Inégalité”, Literally Meaning Inequality

Recorder Technique Essentials ARTICULATION B Y L O B K E S P R E N K E L I N G For recorder players and other wind players TONGUE & AIR Every note begins with an articulation, except when we play slurred. POSTURE In this article we will discuss all types of articulation, but before we start, let's have a look at a prerequisite for articulation to work well: The tongue must be the air stream. totally relaxed within the mouth, with only the tip In order for the tongue to be agile, we need a steady air stream. of the tongue doing the Imagine it as a big river, and the tongue as a little boat floating on the river. Without air, the tongue gets stuck, just like a boat on a shallow or work. empty river bed. The jaw is relaxed and That is why we keep our breath support active, without dropping it neutral and does not between the notes: we must keep the core muscles engaged all the move in a chewing time. A typical mistake we see in children playing the school recorder is movement when we that they don’t articulate and they start and drop their air stream for articulate. Check in the each note. Even in staccato we must not drop our breath support. mirror that it doesn’t! A good exercise, before getting into any type of articulation, is to slur a Where on the palate melody before playing it with articulations. In this way you check if your breath support is consistent, laying the base for a light and efficient should we articulate? articulation.