View of American Flute Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commissioned Flute Choir Pieces Presented By

THE COMMISSIONED FLUTE CHOIR PIECES PRESENTED BY UNIVERSITY/COLLEGE FLUTE CHOIRS AND NFA SPONSORED FLUTE CHOIRS AT NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION ANNUAL CONVENTIONS WITH A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FLUTE CHOIR AND ITS REPERTOIRE DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yoon Hee Kim Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Russel C. Mikkelson Dr. Charles M. Atkinson Karen Pierson Copyright by Yoon Hee Kim 2013 Abstract The National Flute Association (NFA) sponsors a range of non-performance and performance competitions for performers of all ages. Non-performance competitions are: a Flute Choir Composition Competition, Graduate Research, and Newly Published Music. Performance competitions are: Young Artist Competition, High School Soloist Competition, Convention Performers Competition, Flute Choirs Competitions, Professional, Collegiate, High School, and Jazz Flute Big Band, and a Masterclass Competition. These competitions provide opportunities for flutists ranging from amateurs to professionals. University/college flute choirs perform original manuscripts, arrangements and transcriptions, as well as the commissioned pieces, frequently at conventions, thus expanding substantially the repertoire for flute choir. The purpose of my work is to document commissioned repertoire for flute choir, music for five or more flutes, presented by university/college flute choirs and NFA sponsored flute choirs at NFA annual conventions. Composer, title, premiere and publication information, conductor, performer and instrumentation will be included in an annotated bibliography format. A brief history of the flute choir and its repertoire, as well as a history of NFA-sponsored flute choir (1973–2012) will be included in this document. -

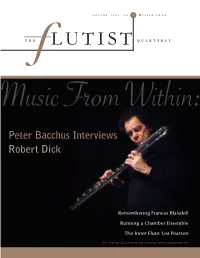

The Flutist Quarterly Volume Xxxv, N O

VOLUME XXXV , NO . 2 W INTER 2010 THE LUTI ST QUARTERLY Music From Within: Peter Bacchus Interviews Robert Dick Remembering Frances Blaisdell Running a Chamber Ensemble The Inner Flute: Lea Pearson THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION , INC :ME:G>:C8: I=: 7DA9 C:L =:69?D>CI ;GDB E:6GA 6 8ji 6WdkZ i]Z GZhi### I]Z cZl 8Vadg ^h EZVgaÉh bdhi gZhedch^kZ VcY ÓZm^WaZ ]ZVY_d^ci ZkZg XgZViZY# Djg XgV[ihbZc ^c ?VeVc ]VkZ YZh^\cZY V eZg[ZXi WaZcY d[ edlZg[ja idcZ! Z[[dgiaZhh Vgi^XjaVi^dc VcY ZmXZei^dcVa YncVb^X gVc\Z ^c dcZ ]ZVY_d^ci i]Vi ^h h^bean V _dn id eaVn# LZ ^ck^iZ ndj id ign EZVgaÉh cZl 8Vadg ]ZVY_d^ci VcY ZmeZg^ZcXZ V cZl aZkZa d[ jcbViX]ZY eZg[dgbVcXZ# EZVga 8dgedgVi^dc *). BZigdeaZm 9g^kZ CVh]k^aaZ! IC (,'&& -%%".),"(',* l l l # e Z V g a [ a j i Z h # X d b Table of CONTENTS THE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXV, N O. 2 W INTER 2010 DEPARTMENTS 5 From the Chair 51 Notes from Around the World 7 From the Editor 53 From the Program Chair 10 High Notes 54 New Products 56 Reviews 14 Flute Shots 64 NFA Office, Coordinators, 39 The Inner Flute Committee Chairs 47 Across the Miles 66 Index of Advertisers 16 FEATURES 16 Music From Within: An Interview with Robert Dick by Peter Bacchus This year the composer/musician/teacher celebrates his 60th birthday. Here he discusses his training and the nature of pedagogy and improvisation with composer and flutist Peter Bacchus. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: a Study of Works by Ian Clarke Christopher Leigh Davis University of Southern Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-1-2012 Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: A Study of Works by Ian Clarke Christopher Leigh Davis University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Davis, Christopher Leigh, "Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: A Study of Works by Ian Clarke" (2012). Dissertations. 634. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/634 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi EXTENDED TECHNIQUES AND ELECTRONIC ENHANCEMENTS: A STUDY OF WORKS BY IAN CLARKE by Christopher Leigh Davis Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts December 2012 ABSTRACT EXTENDED TECHNIQUES AND ELECTRONIC ENHANCEMENTS: A STUDY OF WORKS BY IAN CLARKE by Christopher Leigh Davis December 2012 British flutist Ian Clarke is a leading performer and composer in the flute world. His works have been performed internationally and have been used in competitions given by the National Flute Association and the British Flute Society. Clarke’s compositions are also referenced in the Peters Edition of the Edexcel GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education) Anthology of Music as examples of extended techniques. The significance of Clarke’s works lies in his unique compositional style. His music features sounds and styles that one would not expect to hear from a flute and have elements that appeal to performers and broader audiences alike. -

View 2012 Program

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR IMPROVISED MUSIC SIXTH FESTIVAL/CONFERENCE Improvisation · Self · Community·World February 16-19, 2012 William Paterson University Wayne, New Jersey, USA Keynote artists and performers: Pyeng Threadgill & trio Ikue Mori, Sylvie Courvoisier & Jim Black Mulgrew Miller WyldLyfe Robert Dick & Tom Buckner Karl Berger with the University of Michigan Creative Arts Orchestra And over 50 other artists presenting concerts, panels, talks and workshops! ISIM President’s Welcome ISIM President’s Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the International Society for Improvised Music, I extend to all of you a hearty welcome to the sixth ISIM Festival/Conference. Nothing is more gratifying than gatherings of improvising musicians as our common process, regardless of surface differences in our creative expressions, unites us in ways that are truly unique. As the conference theme suggests, by going deep within our reservoir of creativity, we access subtle dimensions of self—or consciousness—that are the source of connections with not only our immediate communities but the world at large. It is dificult to imagine a moment in history when the need for this improvisation-driven, creativity revolution is greater on individual and collective scales than the present. Please join me in thanking the many individuals, far too many to list, who have been instrumental in making this event happen. Headliners Ikue Mori, Pyeng Threadgill, Wyldlife, Karl Berger, the University of Michigan Creative Arts Orchestra, the William Paterson University jazz group, Mulgrew Miller, Robert Dick, and Thomas Buckner—we could not have asked for a more varied and exciting line-up. ISIM Board members Stephen Nachmanovitch and Bill Johnson have provided invaluable assistance, with Steve working his usual heroics with the ISIM website in between, and sometimes during, his performing and speaking tours. -

050312 Alexa Still.Indd

master’s and doctoral degrees with numerous competition successes. Still then won principal fl ute of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra at the age of 23, and returned home for 11 years. Described as “a National Treasure” (Daily News) in New Zealand, she made regular tours to the U.S. for solo engagements and, in 1996, a Fulbright Award. Since being appointed associate professor of fl ute at University of Colorado at Boulder (1998) she has presented recitals, concertos and master classes in England, Germany, Australia, New Zealand, Slovenia, Mexico, Canada, Korea and across the United States. She gave the Southern Hemisphere premiere of UNIVERSITY OF OREGON • SCHOOL OF MUSIC John Corigliano’s Pied Piper Fantasy with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and has also performed it with the South Arkansas Symphony Beall Concert Hall Saturday evening and the Long Island Philharmonic. Her 12th solo compact disc (the chamber 8:00 p.m. March 12, 2005 music for fl ute by Lowell Liebermann) was released in July 2003 and she recorded another concerto disc in January of 2003. Still was a featured soloist at the National Flute Association conventions in Chicago, Atlanta and Washington D.C. She was program chair for the 31st National Flute Association Convention in 2003. She plays a silver fl ute made for her by UNIVERSITY OF OREGON Brannen Brothers of Boston with gold or wooden head joints by Sanford Drelinger of White Plains, New York. SCHOOL OF MUSIC Nathalie Fortin was born in Montreal, Canada, where she studied piano at the Montreal Conservatory under Madame Anisia Campos. -

Teaching Rhythm: a Comparative Study of Beginning Band and Solo Flute Method Books

MITCHELL, AMANDA K., D.M.A. Teaching Rhythm: A Comparative Study of Beginning Band and Solo Flute Method Books. (2017) Directed by Dr. Michael Burns. 44 pp. Typically, teachers of private instrumental lessons and large ensembles rely on a method book to supplement instruction regarding the fundamentals of music. The method books chosen by these instructors differ due to the nature of the teaching environments. Numerous books have been written specifically for the varied structure of these learning environments, to address various philosophies and approaches. This led to the development of method books specifically used in either private lessons or large ensemble settings. One of the most integral elements of music found in these method books is rhythm. The purpose of this study is to present comparative data related to the content and sequencing of rhythmic instruction in beginning flute method books for both private lesson and large ensemble environments. Four books intended for each instructional setting were used to provide the data for this study. The comprehensive band method books analyzed were Essential Elements for Band,1 Tradition of Excellence,2 Sound Innovations,3 and Measure of Success.4 The solo flute methods analyzed were; 1 Tim Lautzenheiser et al., Essential Elements for Band: Comprehensive Band Method (Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2004). 2 Bruce Pearson and Ryan Nowlin, Tradition of Excellence: Comprehensive Band Method (San Diego: Kjos Music Press, 2010). 3 Robert Sheldon et al., Sound Innovations for Concert Band: A Revolutionary Method for Beginning Musicians (New York: Alfred Music Publishing Co., Inc., 2010). 4 Deborah A. Sheldon et al., Measures of Success: A Comprehensive Band Method. -

Copyright by Mariana Stratta Gariazzo 2005

Copyright by Mariana Stratta Gariazzo 2005 The Treatise Committee for Mariana Stratta Gariazzo certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Argentine Music for Flute with the Employment of Extended Techniques: An Analysis of Selected Works by Eduardo Bértola and Marcelo Toledo Committee: Gerard Béhague, Co-Supervisor Karl Kraber, Co-Supervisor Lorenzo Candelaria Eugenia Costa-Giomi Patrick Hughes Nicolas Shumway Argentine Music for Flute with the Employment of Extended Techniques: An Analysis of Selected Works by Eduardo Bértola and Marcelo Toledo by Mariana Stratta Gariazzo, B.A.; M.M. Treatise Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May, 2005 Dedication I would like to thank my parents, Inés and Jorge Stratta, for their encouragement and support throughout my entire education and their immense generosity in letting me pursue my dreams in spite of the distance. For that, I will be forever grateful. I also extend an immense amount of gratitude to those who accompanied me during the years of my graduate studies. My family-in-law became the main source of encouragement while pursuing my doctoral education. They have witnessed and assisted me through hectic times from the comprehensive exams to researching and so much more that it would not be possible to describe everything in the frame of this note. I am deeply grateful to all of them. Lastly, but most importantly, I would like to dedicate all the effort, gray hair, and time this work has taken to my dear husband, Claudio. -

National Flute Association Convention Marriott Marquis Hotel, New York City August 13 – 16, 2009

National Flute Association Convention Marriott Marquis Hotel, New York City August 13 – 16, 2009 The following is a list of concerts and other event highlights that are open to the public during the NFA Convention. For a complete listing, please visit www.nfaonline.org/convention . Thursday, August 13: 9–10 am American Composers Concert: O’Neil Flutists John Bailey, Virginia Broffitt, April Clayton, Yvonne Chavez Hansbrough, and Lisamarie McGrath perform works of Katherine Hoover, Jennifer Higdon, Randall Snyder, Eric Sessler, and Keith Gates. 10–10:45 am Concerti Redux: Brad Garner performs a new concerto by Glen Cortese and Tadeu Coelho performs Mark Engebretson’s Deliriade-Flute Concerto with Saxophone Quartet with the Red Clay Saxophone Quartet. 2:15–3:30 pm Gotham Gathering: Chamber Music for Mixed Ensembles: Performances by The Indånde Duo, Don Bailey with the Attacca String Quartet, Montpelier Wind Quintet, Barbara Hopkins, and Judith Handler as well as a performance of Jindrich Feld’s newly transcribed Trio for flute, clarinet, and bassoon by Dennette McDermott, Malena McLaren, 2:30–3:30 pm Celebrating Carol Wincenc’s Ruby Anniversary: Gems from New York Composers: Carol Wincenc in recital performing works of Leonard Bernstein, Paul Schoenfield, David Del Tredici, Joan Tower, Edgard Varese, Jonathan Berger, Henry Cowell, Arnold Black, Lukas Foss 4:30–5:30 pm Remembering Frances Blaisdell, Cantor/Jolson First Lady of the Flute: Friends and students celebrate the life of Frances Blaisdell (1912–2009), pioneering flutist and inspirational teacher, with stories, recordings, and video of her historic career. 4:30–5:30 pm Billy Kerr in Concert: Jazz flutist Billy Kerr plays original 4:30–5:45 pm Headliner Concert: Carlo Jans, Marya Martin, and Gergely Ittzés in recital. -

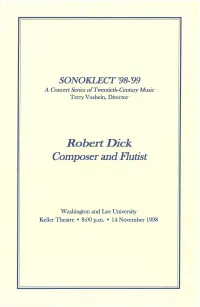

Robert Dick Composer and Flutist

SONOKLECT '98-'99 A Concert Series of Twentieth-Centwy Music Terry Vosbein, Director Robert Dick Composer and Flutist Washington and Lee University Keller Theatre • 8:00 p.m. • 14 November 1998 PROGRAM Flames Must Not Encircle Sides (1980) Afterlight (1973) Flying Lessons - Contemporary Concert Etudes selected from Volume I (1983) and Volume II (1986/87) Satan, Oscillate My Metallic Sonatas, for bass flute (1996) Greenhouse (1991) INTERMISSION Felix on the Helix (1997) for flute with glissando headjoint Piece In Gamelan Style (1979) Re-Illuminations (1985) Lookout (1989) IF, for bass flute in F (1993) All works are by Robert Dick (Multiple Breath Music, BM!) and all arefor the concertflute unless otherwise noted. 3 ROBERT DICK More than any other composer/ performer today, Robert Dick has achieved international recognition for his creation of a rich new musical language for his instrument-the flute. Known worldwide for his original and exciting compositions and improvisations, he has frequently been compared to Paganini and Hendrix as a virtuoso who has not only mastered his instrument but also redefined it. Playing the full range of flutes, from the giant, stand-up contrabass flute through bass flutes in F and C, alto flute, concert flute and piccolos in Ab and C, Dick has performed his music throughout the United States, Europe and Japan. Mr. Dick moved from New York to Switzerland in 1992 and lives with his wife, Regula Muller, in Lucerne. He received the Lucerne Music Prize in 1996 and was commissioned to compose a piece for flute and piano. Entitled Life Concert,this work was premiered in 1997. -

Music Center, Dinkelspiel Audi- MUSIC Torium, and the Knoll, Including Two Theaters for Concert and Recital Productions, Two Rehearsal Halls, and a Small Chamber Hall

The department is housed in Braun Music Center, Dinkelspiel Audi- MUSIC torium, and The Knoll, including two theaters for concert and recital productions, two rehearsal halls, and a small chamber hall. Pianos, or- Emeriti: (Professors) John M. Chowning, Albert Cohen, George Houle, gans, harpsichords, and a variety of early stringed and wind instruments William H. Ramsey, Leonard G. Ratner, Sandor Salgo, Leland C. are available for student use. In addition, advanced students may use fine Smith; (Professors, Performance) Arthur P. Barnes, Marie Gibson, old stringed instruments and bows from the Harry R. Lange Historical Andor Toth Collection (http://www.stanford.edu/group/Music/Langecol.html). Chair: Stephen Hinton The Music Library contains a comprehensive collection of scores, Professors: Karol Berger (on leave), Chris Chafe, Brian Ferneyhough books, and recordings with an emphasis on Western art music. In addition, Associate Professors: Jonathan Berger, Thomas Grey, Stephen Hinton, the Department of Special Collections holds an invaluable collection of William P. Mahrt, Julius O. Smith musical manuscripts and first and early editions, and the Archive of Re- Assistant Professors: Mark Applebaum, Heather Hadlock (on leave corded Sound has a superb collection of historical recordings of all types. Spring), Melissa Hui, Tobias Plebuch (on leave Autumn) For more information on the Department of Music, see the Music Professor (Research): Max V. Mathews Department home page at http://music.stanford.edu. Associate Professors (Teaching): George Barth (Piano), Stephen Sano The Stanford Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (Director of Choral Studies) (CCRMA) is a multi-disciplinary facility where composers and research- Music Senior Lecturers: Stephen Harrison (Violoncello), Gennady Kleyman ers work together using computer-based technology both as an artistic (Violin, Viola), Jennifer Lane (Voice), Thomas Schultz (Piano), medium and as a research tool. -

Music in the University at Large Through Its Courses and Performance Offerings

understanding and enjoyment of music in the University at large through its courses and performance offerings. MUSIC UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMS IN MUSIC Emeriti: (Professors) John M. Chowning, Albert Cohen, George BACHELOR OF ARTS IN MUSIC Houle, William H. Ramsey, Leonard G. Ratner, Leland C. Smith; The undergraduate major in Music is built around a series of (Professors, Performance) Arthur P. Barnes, Marie Gibson; foundation courses in theory, musicianship, and music history, in (Professor, Research) Max V. Mathews addition to performance and the proficiency requirements outlined Chair: Stephen M. Sano below. Majors must complete a minimum of 66 units within the Professors: Jonathan Berger, Karol Berger, Chris Chafe (on leave), department. All required courses for the B.A. in any concentration Brian Ferneyhough (on leave), Thomas Grey, Stephen Hinton, must be taken for a letter grade. Electives may be taken credit/no Julius O. Smith (on leave Autumn) credit, but any courses taken towards concentration requirements Associate Professors: Mark Applebaum, Heather Hadlock, William must also carry a letter grade. P. Mahrt Assistant Professors: Jaroslaw Kapuscinski, Jesse Rodin, Ge Wang SUGGESTED PREPARATION FOR THE MAJOR Professor (Teaching): George Barth (Piano; on leave Winter, Because of the sequence of courses, it takes more than two years Spring) to complete the requirements for the major. Students are required to Associate Professor (Teaching): Stephen M. Sano (Director of meet with the undergraduate student services officer (USSO) in the Choral Studies) department prior to declaring the major. It is highly recommended Associate Professor (Performance): Jindong Cai (Director of that prospective majors schedule this consultation with the USSO as Orchestral Studies) early as possible in their careers in order to plan a program that Courtesy Professor: Paul DeMarinis allows sufficient time for major course work, practice, and Senior Lecturers: Giancarlo Aquilanti (Director of Theory; Wind University requirements outside the major.