The Glissando Headjoint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

É M I L I E Livret D’Amin Maalouf

KAIJA SAARIAHO É M I L I E Livret d’Amin Maalouf Opéra en neuf scènes 2010 OPERA de LYON LIVRET 5 Fiche technique 7 L’argument 10 Le(s) personnage(s) 16 ÉMILIE CAHIER de LECTURES Voltaire 37 Épitaphe pour Émilie du Châtelet Kaija Saariaho 38 Émilie pour Karita Émilie du Châtelet 43 Les grandes machines du bonheur Serge Lamothe 48 Feu, lumière, couleurs, les intuitions d’Émilie 51 Les derniers mois de la dame des Lumières Émilie du Châtelet 59 Mon malheureux secret 60 Je suis bien indignée de vous aimer autant 61 Voltaire Correspondance CARNET de NOTES Kaija Saariaho 66 Repères biographiques 69 Discographie, Vidéographie, Internet Madame du Châtelet 72 Notice bibliographique Amin Maalouf 73 Repères biographiques 74 Notice bibliographique Illustration. Planches de l’Encyclopédie de Diderot et D’Alembert, Paris, 1751-1772 Gravures du Recueil de planches sur les sciences, les arts libéraux & les arts méchaniques, volumes V & XII LIVRET Le livret est écrit par l’écrivain et romancier Amin Maalouf. Il s’inspire de la vie et des travaux d’Émilie du Châtelet. Émilie est le quatrième livret composé par Amin Maalouf pour et avec Kaija Saariaho, après L’Amour de loin, Adriana Mater 5 et La Passion de Simone. PARTITION Kaija Saariaho commence l’écriture de la partition orches- trale en septembre 2008 et la termine le 19 mai 2009. L’œuvre a été composée à Paris et à Courtempierre (Loiret). Émilie est une commande de l’Opéra national de Lyon, du Barbican Centre de Londres et de la Fondation Gulbenkian. Elle est publiée par Chester Music Ltd. -

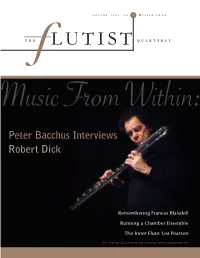

The Flutist Quarterly Volume Xxxv, N O

VOLUME XXXV , NO . 2 W INTER 2010 THE LUTI ST QUARTERLY Music From Within: Peter Bacchus Interviews Robert Dick Remembering Frances Blaisdell Running a Chamber Ensemble The Inner Flute: Lea Pearson THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION , INC :ME:G>:C8: I=: 7DA9 C:L =:69?D>CI ;GDB E:6GA 6 8ji 6WdkZ i]Z GZhi### I]Z cZl 8Vadg ^h EZVgaÉh bdhi gZhedch^kZ VcY ÓZm^WaZ ]ZVY_d^ci ZkZg XgZViZY# Djg XgV[ihbZc ^c ?VeVc ]VkZ YZh^\cZY V eZg[ZXi WaZcY d[ edlZg[ja idcZ! Z[[dgiaZhh Vgi^XjaVi^dc VcY ZmXZei^dcVa YncVb^X gVc\Z ^c dcZ ]ZVY_d^ci i]Vi ^h h^bean V _dn id eaVn# LZ ^ck^iZ ndj id ign EZVgaÉh cZl 8Vadg ]ZVY_d^ci VcY ZmeZg^ZcXZ V cZl aZkZa d[ jcbViX]ZY eZg[dgbVcXZ# EZVga 8dgedgVi^dc *). BZigdeaZm 9g^kZ CVh]k^aaZ! IC (,'&& -%%".),"(',* l l l # e Z V g a [ a j i Z h # X d b Table of CONTENTS THE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXV, N O. 2 W INTER 2010 DEPARTMENTS 5 From the Chair 51 Notes from Around the World 7 From the Editor 53 From the Program Chair 10 High Notes 54 New Products 56 Reviews 14 Flute Shots 64 NFA Office, Coordinators, 39 The Inner Flute Committee Chairs 47 Across the Miles 66 Index of Advertisers 16 FEATURES 16 Music From Within: An Interview with Robert Dick by Peter Bacchus This year the composer/musician/teacher celebrates his 60th birthday. Here he discusses his training and the nature of pedagogy and improvisation with composer and flutist Peter Bacchus. -

Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: a Study of Works by Ian Clarke Christopher Leigh Davis University of Southern Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-1-2012 Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: A Study of Works by Ian Clarke Christopher Leigh Davis University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Davis, Christopher Leigh, "Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: A Study of Works by Ian Clarke" (2012). Dissertations. 634. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/634 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi EXTENDED TECHNIQUES AND ELECTRONIC ENHANCEMENTS: A STUDY OF WORKS BY IAN CLARKE by Christopher Leigh Davis Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts December 2012 ABSTRACT EXTENDED TECHNIQUES AND ELECTRONIC ENHANCEMENTS: A STUDY OF WORKS BY IAN CLARKE by Christopher Leigh Davis December 2012 British flutist Ian Clarke is a leading performer and composer in the flute world. His works have been performed internationally and have been used in competitions given by the National Flute Association and the British Flute Society. Clarke’s compositions are also referenced in the Peters Edition of the Edexcel GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education) Anthology of Music as examples of extended techniques. The significance of Clarke’s works lies in his unique compositional style. His music features sounds and styles that one would not expect to hear from a flute and have elements that appeal to performers and broader audiences alike. -

View 2012 Program

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR IMPROVISED MUSIC SIXTH FESTIVAL/CONFERENCE Improvisation · Self · Community·World February 16-19, 2012 William Paterson University Wayne, New Jersey, USA Keynote artists and performers: Pyeng Threadgill & trio Ikue Mori, Sylvie Courvoisier & Jim Black Mulgrew Miller WyldLyfe Robert Dick & Tom Buckner Karl Berger with the University of Michigan Creative Arts Orchestra And over 50 other artists presenting concerts, panels, talks and workshops! ISIM President’s Welcome ISIM President’s Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the International Society for Improvised Music, I extend to all of you a hearty welcome to the sixth ISIM Festival/Conference. Nothing is more gratifying than gatherings of improvising musicians as our common process, regardless of surface differences in our creative expressions, unites us in ways that are truly unique. As the conference theme suggests, by going deep within our reservoir of creativity, we access subtle dimensions of self—or consciousness—that are the source of connections with not only our immediate communities but the world at large. It is dificult to imagine a moment in history when the need for this improvisation-driven, creativity revolution is greater on individual and collective scales than the present. Please join me in thanking the many individuals, far too many to list, who have been instrumental in making this event happen. Headliners Ikue Mori, Pyeng Threadgill, Wyldlife, Karl Berger, the University of Michigan Creative Arts Orchestra, the William Paterson University jazz group, Mulgrew Miller, Robert Dick, and Thomas Buckner—we could not have asked for a more varied and exciting line-up. ISIM Board members Stephen Nachmanovitch and Bill Johnson have provided invaluable assistance, with Steve working his usual heroics with the ISIM website in between, and sometimes during, his performing and speaking tours. -

Developments in Extended Vocal Technique Music

PART ONE Fundamental Techniques Part One – Fundamental Techniques In his essay Sprech und Gesangsschule (Neue Vokalpratiken) (School for Speech and Singing (New Vocal Practices)) (1972), the German composer and theologian Dieter Schnebel provides a thorough and innovative investigation into the production, usage and latent possibilities of new vocal techniques. Schnebel comments on the inherent limitations of conventional vocal performance practices and notations and their relative inaccuracy and unsuitability when applied to extended vocal techniques. He goes on to outline the main physical mechanisms and processes involved in the production of vowels and consonants, suggesting new ways in which to expand the range of attainable sounds through the combination of various mouth (vowel) positions with different noise (consonant) sounds. He discusses the importance of breath control in the shaping of these sounds, as well as the actual use of various modes of breath as compositional material, stating that ‘Audible and inaudible breath processes would, so to speak, form the basis of the artistic processes... Breath, crossing the line of audibility, becomes art itself, built from shaped fricatives’1 However, such techniques are seen not only as processes with which to create new sounds but also as a means of liberating both the voice and the consciousness of the performer. Schnebel writes: ‘Such operations lead, so to speak, into the sound production itself. Taken further, they can themselves attain form, without the overlapping unities like words or even sentences being adjusted. That is, the articulation process becomes the object of the composition...This demands a conscious knowledge of what is happening with the articulation’2 With reference to his composition Maulwerke he adds: ‘...the content is expressed no longer mediated through the vehicle of a still rudimentary text, but rather directly. -

VB3 / A/ O,(S0-02

/VB3 / A/ O,(s0-02 A SURVEY OF THE RESEARCH LITERATURE ON THE FEMALE HIGH VOICE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Roberta M. Stephen, B. Mus., A. Mus., A.R.C.T. Denton, Texas December, 1988 Stephen, Roberta M., Survey of the Research Literature on the Female High Voice. Master of Arts (Music), December, 1988, 161 pp., 11 tables, 13 illustrations, 1 appendix, bibliography, partially annotated, 136 titles. The location of the available research literature and its relationship to the pedagogy of the female high voice is the subject of this thesis. The nature and pedagogy of the female high voice are described in the first four chapters. The next two chapters discuss maintenance of the voice in conventional and experimental repertoire. Chapter seven is a summary of all the pedagogy. The last chapter is a comparison of the nature and the pedagogy of the female high voice with recommended areas for further research. For instance, more information is needed to understand the acoustic factors of vibrato, singer's formant, and high energy levels in the female high voice. PREFACE The purpose of this thesis is to collect research about the female high voice and to assemble the pedagogy. The science and the pedagogy will be compared to show how the two subjects conform, where there is controversy, and where more research is needed. Information about the female high voice is scattered in various periodicals and books; it is not easily found. -

050312 Alexa Still.Indd

master’s and doctoral degrees with numerous competition successes. Still then won principal fl ute of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra at the age of 23, and returned home for 11 years. Described as “a National Treasure” (Daily News) in New Zealand, she made regular tours to the U.S. for solo engagements and, in 1996, a Fulbright Award. Since being appointed associate professor of fl ute at University of Colorado at Boulder (1998) she has presented recitals, concertos and master classes in England, Germany, Australia, New Zealand, Slovenia, Mexico, Canada, Korea and across the United States. She gave the Southern Hemisphere premiere of UNIVERSITY OF OREGON • SCHOOL OF MUSIC John Corigliano’s Pied Piper Fantasy with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and has also performed it with the South Arkansas Symphony Beall Concert Hall Saturday evening and the Long Island Philharmonic. Her 12th solo compact disc (the chamber 8:00 p.m. March 12, 2005 music for fl ute by Lowell Liebermann) was released in July 2003 and she recorded another concerto disc in January of 2003. Still was a featured soloist at the National Flute Association conventions in Chicago, Atlanta and Washington D.C. She was program chair for the 31st National Flute Association Convention in 2003. She plays a silver fl ute made for her by UNIVERSITY OF OREGON Brannen Brothers of Boston with gold or wooden head joints by Sanford Drelinger of White Plains, New York. SCHOOL OF MUSIC Nathalie Fortin was born in Montreal, Canada, where she studied piano at the Montreal Conservatory under Madame Anisia Campos. -

Multiphonics of the Grand Piano – Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets

Multiphonics of the Grand Piano – Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets Juhani VESIKKALA Written work, Composition MA Department of Classical Music Sibelius Academy / University of the Arts, Helsinki 2016 SIBELIUS-ACADEMY Abstract Kirjallinen työ Title Number of pages Multiphonics of the Grand Piano - Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets 86 + appendices Author(s) Term Juhani Topias VESIKKALA Spring 2016 Degree programme Study Line Sävellys ja musiikinteoria Department Klassisen musiikin osasto Abstract The aim of my study is to enable a broader knowledge and compositional use of the piano multiphonics in current music. This corpus of text will benefit pianists and composers alike, and it provides the answers to the questions "what is a piano multiphonic", "what does a multiphonic sound like," and "how to notate a multiphonic sound". New terminology will be defined and inaccuracies in existing terminology will be dealt with. The multiphonic "mode of playing" will be separated from "playing technique" and from flageolets. Moreover, multiphonics in the repertoire are compared from the aspects of composition and notation, and the portability of multiphonics to the sounds of other instruments or to other mobile playing modes of the manipulated grand piano are examined. Composers tend to use multiphonics in a different manner, making for differing notational choices. This study examines notational choices and proposes a notation suitable for most situations, and notates the most commonly produceable multiphonic chords. The existence of piano multiphonics will be verified mathematically, supported by acoustic recordings and camera measurements. In my work, the correspondence of FFT analysis and hearing will be touched on, and by virtue of audio excerpts I offer ways to improve as a listener of multiphonics. -

Saariaho–Petals– Context, Structure, Sonority Music Year Group: 12/13 and Melody

Topic: Kaija Saariaho–Petals– Context, structure, sonority Music Year Group: 12/13 and melody. 1. Context and structure 3. Sonority – How the instruments are used 4. Key vocabulary Ralph Finnish composer, who has studied in Artificial A harmonic produced on a stopped Spectralists A group of French Vaughan- Helsinki, Germany and Paris, where she 1 Harmon string on a stringed instrument. E.g. composers who use Williams now lives. Interests included computer- ic Section 5. 1 computer analysis of based sound spectrum analysis, Double Playing two notes at the same time sound as the basis for 1 electronic music, music combining live 2 Stoppin on a string instrument. E.g. Stave 18. composition. performance and electronics and the g Nympheas Composition in 1987 for use of computers in the actual string quartet and composition of music. Identifies as a Electro Making a sound louder by electronic nic means. 2 electronics, which spectralist composer. 3 amplific Saariaho uses as a basis Colouristic Slower moving passages where the ation for the opening. 2 emphasis is on changing sounds of long Harmoniser A device that detunes’ notes. Section 1, 3, 5 and 7. Fundam The musical pitch of a note that is 4 ental perceived as the lowest partial the input pitch by Energetic Section with short note lengths and present. 3 adding pitches a quarter 3 faster moving passages. Section 2, 4 and tone above and below Glissan Slide from one note to another. E.g. 6. 5 simultaneously. do Stave 18. Staves Rather than using bars, everything is Reverberation A sustaining effect that divided into staves. -

New Music Festival November 5-9, 2018

University of Louisville School of Music Presents the Annual New Music Festival November 5-9, 2018 FEATURED GUEST COMPOSER Amy Williams GUEST ARTISTS Sam Pluta Elysian Trombone Consort A/Tonal Ensemble New Music Festival November 5-9, 2018 Amy Williams featured composer Table of Contents Greetings From Dr. Christopher Doane, Dean of the School of Music 3 Biography Amy Williams, Featured Composer 5 Sunday, November 4 Morton Feldman: His Life & Works Program 6 Monday, November 5 Faculty Chamber Music Program 10 Tuesday, November 6 Electronic Music Program 18 Wednesday, November 7 University Symphony Orchestra Program 22 Personnel 25 Thursday, November 8 Collegiate Chorale & Cardinal Singers Program 26 Personnel 32 Friday, November 9 New Music Ensemble & Wind Ensemble Program 34 Personnel 40 Guest Artist Biographies 41 Composer Biographies 43 1 Media partnership provided by Louisville Public Media 502-852-6907 louisville.edu/music facebook.com/uoflmusic Additional 2018 New Music Festival Events: Monday, November 5, 2018 Music Building Room LL28 Computer Music Composition Seminar with Sam Pluta Wednesday, November 7, 2018 Music Building Room 125 Composition Seminar with Amy Williams Thursday, November 8, 2018 Bird Recital Hall Convocation Lecture with Amy Williams To access the New Music Festival program: For Apple users, please scan the accompanying QR code. For Android users, please visit www.qrstuff.com/scan and allow the website to access your device’s camera. The New Music Festival Organizing Committee Dr. John Ritz, chair Dr. Kent Hatteberg Professor Kimcherie Lloyd Dr. Frederick Speck Dr. Krzysztof Wołek 2 The School of Music at the University of Louisville is strongly identified with the performance of contemporary music and the creation of new music. -

Copyright by Mariana Stratta Gariazzo 2005

Copyright by Mariana Stratta Gariazzo 2005 The Treatise Committee for Mariana Stratta Gariazzo certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Argentine Music for Flute with the Employment of Extended Techniques: An Analysis of Selected Works by Eduardo Bértola and Marcelo Toledo Committee: Gerard Béhague, Co-Supervisor Karl Kraber, Co-Supervisor Lorenzo Candelaria Eugenia Costa-Giomi Patrick Hughes Nicolas Shumway Argentine Music for Flute with the Employment of Extended Techniques: An Analysis of Selected Works by Eduardo Bértola and Marcelo Toledo by Mariana Stratta Gariazzo, B.A.; M.M. Treatise Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May, 2005 Dedication I would like to thank my parents, Inés and Jorge Stratta, for their encouragement and support throughout my entire education and their immense generosity in letting me pursue my dreams in spite of the distance. For that, I will be forever grateful. I also extend an immense amount of gratitude to those who accompanied me during the years of my graduate studies. My family-in-law became the main source of encouragement while pursuing my doctoral education. They have witnessed and assisted me through hectic times from the comprehensive exams to researching and so much more that it would not be possible to describe everything in the frame of this note. I am deeply grateful to all of them. Lastly, but most importantly, I would like to dedicate all the effort, gray hair, and time this work has taken to my dear husband, Claudio. -

Downloads/9215D25f931f4d419461a88825f3f33f20160622021223/Cb7be6

JOAN LA BARBARA’S EARLY EXPLORATIONS OF THE VOICE by Samara Ripley B.Mus., Mount Allison University, 2014 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2016 © Samara Ripley, 2016 Abstract Experimental composer and performer Joan La Barbara treats the voice as a musical instrument. Through improvisation, she has developed an array of signature sounds, or extended vocal techniques, that extend the voice beyond traditional conceptions of Western classical singing. At times, her signature sounds are primal and unfamiliar, drawing upon extreme vocal registers and multiple simultaneous pitches. In 2003, La Barbara released Voice is the Original Instrument, a two-part album that comprises a selection of her earliest works from 1974 – 1980. The compositions on this album reveal La Barbara’s experimental approach to using the voice. Voice Piece: One-Note Internal Resonance Investigation explores the timbral palette within a single pitch. Circular Song plays with the necessity of a singer’s breath by vocalizing, and therefore removing, all audible inhalations and exhalations. Hear What I Feel brings the sense of touch into an improvisatory composition and performance experience. In October Music: Star Showers and Extraterrestrials, La Barbara moves past experimentation and layers her different sounds into a cohesive piece of music. This thesis is a study of La Barbara’s treatment of the voice in these four early works. I will frame my discussion with theories of the acousmatic by Mladen Dolar and Brian Kane and will also draw comparisons with Helmut Lachnemann’s musique concrète instrumentale works.