Copyright by Mariana Stratta Gariazzo 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revista Del Instituto De Investigación Musicológica "Carlos Vega"

REVISTA DEL INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIÓN MUSICOLÓGICA “CARLOS VEGA” REVISTA DEL INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIÓN MUSICOLÓGICA “CARLOS VEGA” Año XXIX– N° 29– 2015 FACULTAD DE ARTES Y CIENCIAS MUSICALES PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA ARGETINA SANTA MARÍA DE LOS BUENOS AIRES UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA ARGENTINA SANTA MARÍA DE LOS BUENOS AIRES Rector: Pbro. Dr. Víctor Manuel Fernández FACULTAD DE ARTES Y CIENCIAS MUSICALES Decana: Dra. Diana Fernández Calvo INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIÓN MUSICOLÓGICA “CARLOS VEGA” Director: Dr. Pablo Cetta Editora: Lic. Nilda G. Vineis Consejo editorial: Dr. Antonio Corona Alcalde (Universidad Nacional de México), Dra. Marita Fornaro Bordolli (Universidad de la República de Uruguay), Dra. Roxana Gardes de Fernández (Universidad Católica Argentina), Dr. Juan Ortiz de Zárate (Universidad Católica Argentina), Dra. Luisa Vilar Payá (Universidad de California, Berkeley, EEUU y Columbia University, New York, EEUU). Referato Dr. Enrique Cámara de Landa (Universidad de Valladolid, España), Dr. Oscar Pablo Di Lisica (Universidad Nacional de Quilmes), Dra. Marita Fornaro Bordolli (Universidad de la República de Uruguay), Dr. Juan Ortiz de Zárate (Universidad Católica Argentina), Dra. Amalia Suarez Urtubey (Universidad Católica Argentina) Los artículos y las reseñas firmados no reflejan necesariamente la opinión de los editores. Diseño: Dr. Julián Mosca Imagen de tapa: "La zarzuela", Madrid, estampilla alusiva Los autores de los artículos publicados en el presente número autorizan a la editorial, en forma no exclusiva, para que incorpore la versión digital de los mismos al Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad Católica Argentina como así también a otras bases de datos que considere de relevancia académica. El Instituto está interesado en intercambiar publicaciones .The Institute is interested in interchanging publications. -

Oscar Pablo Di Liscia (1955): Un Compositor Argentino Contemporáneo

FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE DIDÁCTICA DE LA EXPRESIÓN MUSICAL, PLÁSTICA Y CORPORAL SECCIÓN DE MÚSICA TESIS DOCTORAL Oscar Pablo Di Liscia (1955): un compositor argentino contemporáneo Aportaciones biográficas, entrevistas cualitativas, catalogación de obras y aproximaciones analíticas (1955-2013) Presentada por Juan Manuel Abras Contel Para optar al grado de doctor por la Universidad de Valladolid Dirigida por Prof. Dra. Victoria Cavia Naya 2016 Oscar Pablo Di Liscia (1955): un compositor argentino contemporáneo Aportaciones biográficas, entrevistas cualitativas, catalogación de obras y aproximaciones analíticas (1955-2013) A mi madre, María Amalia: la persona a quien todo debo y única razón de mi vida Agradecimientos Deo gratias et Mariae. Sea público y manifiesto mi renovado agradecimiento a Victoria Cavia Naya, Enrique Cámara de Landa, María Antonia Virgili Blanquet, Juan P. Arregui y Oscar Pablo Di Liscia. VII Índice de ilustraciones Ilustración 1. Relaciones funcionales entre tesis, fuentes y niveles. ............................. 27 Ilustración 2. Primera entrevista. Nube de palabras. ................................................ 251 Ilustración 3. Segunda entrevista. Nube de palabras. ................................................ 257 Ilustración 4. Que sean dos (espacios 1-9). Intervalos armónicos. ............................. 320 Ilustración 5. Que sean dos (espacios 1-9). Intervalos armónicos. ............................. 320 Ilustración 6. Que sean dos (espacios 1-9). Relaciones interválicas. .......................... 321 Ilustración 7. Que sean dos (espacios 1-24). Relación pitch class sets-espacios. .......... 323 Ilustración 8. Que sean dos (espacios 68-72). Pitch class sets e intervalos melódicos. 324 Ilustración 9. Que sean dos (espacios 68-72). Intervalos armónicos. .......................... 324 Ilustración 10. Que sean dos (espacios 68-72). Relaciones interválicas. ..................... 325 Ilustración 11. Que sean dos (espacios 68-72). Pitch class sets. -

Music and Spiritual Feminism: Religious Concepts and Aesthetics

Music and spiritual feminism: Religious concepts and aesthe� cs in recent musical proposals by women ar� sts. MERCEDES LISKA PhD in Social Sciences at University of Buenos Aires. Researcher at CONICET (National Council of Scientifi c and Technical Research). Also works at Gino Germani´s Institute (UBA) and teaches at the Communication Sciences Volume 38 Graduation Program at UBA, and at the Manuel de Falla Conservatory as well. issue 1 / 2019 Email: [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9692-6446 Contracampo e-ISSN 2238-2577 Niterói (RJ), 38 (1) abr/2019-jul/2019 Contracampo – Brazilian Journal of Communication is a quarterly publication of the Graduate Programme in Communication Studies (PPGCOM) at Fluminense Federal University (UFF). It aims to contribute to critical refl ection within the fi eld of Media Studies, being a space for dissemination of research and scientifi c thought. TO REFERENCE THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE USE THE FOLLOWING CITATION: Liska, M. (2019). Music and spiritual feminism. Religious concepts and aesthetics in recent musical proposals by women artists. Contracampo – Brazilian Journal of Communication, 38 (1). Submitted on: 03/11/2019 / Accepted on: 04/23/2019 DOI – http://dx.doi.org/10.22409/contracampo.v38i1.28214 Abstract The spiritual feminism appears in the proposal of diverse women artists of Latin American popular music created recently. References linked to personal and social growth and well-being, to energy balance and the ancestral feminine powers, that are manifested in the poetic and thematic language of songs, in the visual, audiovisual and performative composition of the recitals. A set of multi religious representations present in diff erent musical aesthetics contribute to visualize female powers silenced by the patriarchal system. -

The Commissioned Flute Choir Pieces Presented By

THE COMMISSIONED FLUTE CHOIR PIECES PRESENTED BY UNIVERSITY/COLLEGE FLUTE CHOIRS AND NFA SPONSORED FLUTE CHOIRS AT NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION ANNUAL CONVENTIONS WITH A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FLUTE CHOIR AND ITS REPERTOIRE DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yoon Hee Kim Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Russel C. Mikkelson Dr. Charles M. Atkinson Karen Pierson Copyright by Yoon Hee Kim 2013 Abstract The National Flute Association (NFA) sponsors a range of non-performance and performance competitions for performers of all ages. Non-performance competitions are: a Flute Choir Composition Competition, Graduate Research, and Newly Published Music. Performance competitions are: Young Artist Competition, High School Soloist Competition, Convention Performers Competition, Flute Choirs Competitions, Professional, Collegiate, High School, and Jazz Flute Big Band, and a Masterclass Competition. These competitions provide opportunities for flutists ranging from amateurs to professionals. University/college flute choirs perform original manuscripts, arrangements and transcriptions, as well as the commissioned pieces, frequently at conventions, thus expanding substantially the repertoire for flute choir. The purpose of my work is to document commissioned repertoire for flute choir, music for five or more flutes, presented by university/college flute choirs and NFA sponsored flute choirs at NFA annual conventions. Composer, title, premiere and publication information, conductor, performer and instrumentation will be included in an annotated bibliography format. A brief history of the flute choir and its repertoire, as well as a history of NFA-sponsored flute choir (1973–2012) will be included in this document. -

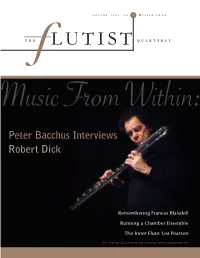

The Flutist Quarterly Volume Xxxv, N O

VOLUME XXXV , NO . 2 W INTER 2010 THE LUTI ST QUARTERLY Music From Within: Peter Bacchus Interviews Robert Dick Remembering Frances Blaisdell Running a Chamber Ensemble The Inner Flute: Lea Pearson THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION , INC :ME:G>:C8: I=: 7DA9 C:L =:69?D>CI ;GDB E:6GA 6 8ji 6WdkZ i]Z GZhi### I]Z cZl 8Vadg ^h EZVgaÉh bdhi gZhedch^kZ VcY ÓZm^WaZ ]ZVY_d^ci ZkZg XgZViZY# Djg XgV[ihbZc ^c ?VeVc ]VkZ YZh^\cZY V eZg[ZXi WaZcY d[ edlZg[ja idcZ! Z[[dgiaZhh Vgi^XjaVi^dc VcY ZmXZei^dcVa YncVb^X gVc\Z ^c dcZ ]ZVY_d^ci i]Vi ^h h^bean V _dn id eaVn# LZ ^ck^iZ ndj id ign EZVgaÉh cZl 8Vadg ]ZVY_d^ci VcY ZmeZg^ZcXZ V cZl aZkZa d[ jcbViX]ZY eZg[dgbVcXZ# EZVga 8dgedgVi^dc *). BZigdeaZm 9g^kZ CVh]k^aaZ! IC (,'&& -%%".),"(',* l l l # e Z V g a [ a j i Z h # X d b Table of CONTENTS THE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXV, N O. 2 W INTER 2010 DEPARTMENTS 5 From the Chair 51 Notes from Around the World 7 From the Editor 53 From the Program Chair 10 High Notes 54 New Products 56 Reviews 14 Flute Shots 64 NFA Office, Coordinators, 39 The Inner Flute Committee Chairs 47 Across the Miles 66 Index of Advertisers 16 FEATURES 16 Music From Within: An Interview with Robert Dick by Peter Bacchus This year the composer/musician/teacher celebrates his 60th birthday. Here he discusses his training and the nature of pedagogy and improvisation with composer and flutist Peter Bacchus. -

El Rol Del Intérprete En La Música Electrónica: Estado De La Cuestión

Anache, Damián El rol del intérprete en la música electrónica: estado de la cuestión Décima Jornada de la Música y la Musicología, 2013 Jornadas Interdisciplinarias de Investigación Facultad de Artes y Ciencias Musicales - UCA Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la Institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Anache, Damián. “El rol del intérprete en la música electrónica : estado de la cuestión” [en línea].Jornada de la Música y la Musicología. Jornadas Interdisciplinarias de Investigación : Investigación, creación, re-creación y performance, X, 4-6 septiembre 2013. Universidad Católica Argentina. Facultad de Artes y Ciencias Musicales; Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega”, Buenos Aires. Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/ponencias/rol-interprete-musica-electronica-anache.pdf [Fecha de consulta: ….] Actas de la Décima Semana de la Música y la Musicología. Jornadas Interdisciplinarias de Investigación. Subsidio FONCYT RC-2013-0119 (en trámite) EL ROL DEL INTÉRPRETE EN LA MÚSICA ELECTRÓNICA - ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN DAMIÁN ANACHE ENSAYO Resumen Desde sus inicios, la interpretación ha sido la pieza clave para que exista la música. No obstante, a partir de la implementación de los medios electroacústicos, ese lugar determinante de la instancia interpretativa dejó de ser indispensable y tanto el campo de acción de la interpretación, como sus posibilidades de ser abordado se han expandido. Durante décadas, esas nuevas condiciones estuvieron supeditadas a las limitaciones de la tecnología para operar sonido en tiempo real. -

Toward a Redefinition of Musical Learning in the Saxophone Studios of Argentina

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Toward a redefinition of musical learning in the saxophone studios of Argentina Mauricio Gabriel Aguero Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Aguero, Mauricio Gabriel, "Toward a redefinition of musical learning in the saxophone studios of Argentina" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2221. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2221 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. TOWARD A REDEFINITION OF MUSICAL LEARNING IN THE SAXOPHONE STUDIOS OF ARGENTINA A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Mauricio Gabriel Agüero B.M., Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, 2005 M.M., University of Florida, 2010 December 2013 Acknowledgments This monograph would not have been possible without the help of many people. Most important, I want to thank to my Professor and advisor Griffin Campbell, who guided my studies at LSU for the last three years with his musical passion, artistry and great teaching ability. As a brilliant saxophonist and thoughtful educator, Professor Campbell has been an important mentor and role model for me. -

ISU Symphony Orchestra

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music Spring 3-25-2018 ISU Symphony Orchestra Glenn Block, Director Illinois State University Jorge Lhez, Conductor Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Block,, Glenn Director and Lhez,, Jorge Conductor, "ISU Symphony Orchestra" (2018). School of Music Programs. 3657. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/3657 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THANKYOU Illinois State University College of Fine Arts Illinois State University College ofFine Arts School of Music Jean M. Miller, Dean, College of Fine Arts Laurie Thompson-Merriman, Associate Dean of Creative Scholarship and Planning Janet Tulley, Assistant Denn of Acndemic Programs and Student Affairs Steve Parsons, Director, School of Music Janet Wilson, Director, School of Theatre and Dance l'.lichael \Ville, Director, School of Art Aaron Paolucci, Pro~m Director, Arts Technology • • Nick Benson, Center for Performing Arts l\fanager Barry Blinderm:m, Director, University Galleries Illinois State University School ofMusic Illinois State University Symphony Orchestra A. Oforiwaa Aduonurn, E1bnon111Iimlog Marie I-~bonville, MJ1sitology Allison Alcorn, M11si,vlog Katherine J. Lewis, Viola Debra Austin, Voia Roy D. l\Iagnuson, Theory a11d Con,po.ritio11 Glenn Block, M11sic Director Mark Babbitt, Trombon, Anthony Marinello III, Diru/orofBa11ds Jorge Lhez (Argentina), Guest Conductor Emily Beinbom, Murie Th,rapy Thomas Marko, Dirrclor of]a:::.:;_ Studi,s Glenn Block, Orrhu/T/1 and Conduclin.!, Rose Marshack, A-fmi,· Bmin,ss a11d Arts T,dmolog Shela Bondurant Koehler, Mmk Edrm,tion Joseph Matson, Musimlog Karyl K. -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: a Study of Works by Ian Clarke Christopher Leigh Davis University of Southern Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-1-2012 Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: A Study of Works by Ian Clarke Christopher Leigh Davis University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Davis, Christopher Leigh, "Extended Techniques and Electronic Enhancements: A Study of Works by Ian Clarke" (2012). Dissertations. 634. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/634 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi EXTENDED TECHNIQUES AND ELECTRONIC ENHANCEMENTS: A STUDY OF WORKS BY IAN CLARKE by Christopher Leigh Davis Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts December 2012 ABSTRACT EXTENDED TECHNIQUES AND ELECTRONIC ENHANCEMENTS: A STUDY OF WORKS BY IAN CLARKE by Christopher Leigh Davis December 2012 British flutist Ian Clarke is a leading performer and composer in the flute world. His works have been performed internationally and have been used in competitions given by the National Flute Association and the British Flute Society. Clarke’s compositions are also referenced in the Peters Edition of the Edexcel GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education) Anthology of Music as examples of extended techniques. The significance of Clarke’s works lies in his unique compositional style. His music features sounds and styles that one would not expect to hear from a flute and have elements that appeal to performers and broader audiences alike. -

The Development of the Flute As a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era

Musical Offerings Volume 2 Number 1 Spring 2011 Article 2 5-1-2011 The Development of the Flute as a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era Anna J. Reisenweaver Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Musicology Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Reisenweaver, Anna J. (2011) "The Development of the Flute as a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era," Musical Offerings: Vol. 2 : No. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2011.2.1.2 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol2/iss1/2 The Development of the Flute as a Solo Instrument from the Medieval to the Baroque Era Document Type Article Abstract As one of the oldest instruments known to mankind, the flute is present in some form in nearly every culture and ethnic group in the world. However, in Western music in particular, the flute has taken its place as an important part of musical culture, both as a solo and an ensemble instrument. The flute has also undergone its most significant technological developments in Western musical culture, moving from the bone keyless flutes of the Prehistoric era to the gold and silver instruments known to performers today. -

Alla Argentina “In the Style of Argentina”

Alla Argentina “In the Style of Argentina” Author and School: Mary McCartney, Floresta Elementary School Subject Area: Music Education Topic: Music and Dance of Argentina Grade Level: K – 5 Time Frame: 6 – 9 weeks with classes meeting 1 time per week Unit Summary: To show the similarities and differences between Argentine and American music, dance and instruments. Through these comparisons, students should be able to conclude that even though we all may look different, talk different, and have different cultural dances, music and celebrations, we are all basically the same. Unit Overview Stage 1 – Desired Results Established Goal(s): MU.3.H.1.1: Compare indigenous instruments of specified cultures. MU.3.H.1.3: Identify timbre(s) in music from a variety of cultures MU.4.H.1.1: Examine and describe a cultural tradition, other than one’s own, learned through its musical style and/or use of authentic instruments. MU.4.H.1.3: Identify pieces of music that originated from cultures other than one’s own. MU.4.H.2.2: Identify ways in which individuals of varying ages and cultures experience music. MU.5.H.1.1: Identify the purposes for which music is used within various cultures. MU.5.H.1.3: Compare stylistic and musical features in works originating from different cultures. Understanding(s) Essential Question(s): Students will understand and explore the What are the similarities and differences similarities and differences between Argentine between Argentine and American music, and American music, dance and instruments. dance and instruments? Through these comparisons, students should be How are the cultures of Argentina and the able to conclude that even though we all may United States the same or different? look different, talk different, and have different How do these similarities and differences cultural dances, music and celebrations, we are show that the people of Argentina and the all basically the same.