1. a Paradigmatic Case of Disagreement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Des Classés Sur Liste Complémentaire Du ENS Paris-Saclay

Session 2021 Liste des classés sur liste complémentaire du 06/07/2021 06:59 ENS Paris-Saclay - PSI 12927 Monsieur GRZECZKOWICZ Rémi, Jacques, Edouard 37 25148 Madame KOCH Marie-Liesse, Inès Isabelle 38 13389 Monsieur SCHULTZ Vincent, Arthur, François 39 258 Monsieur SOUFFRONT Alexandre, Roger, William 40 42457 Monsieur LE CORRE Baptiste, Pierre, Gildas 41 9319 Monsieur PLANCHE Victor, Louis 42 31393 Madame PLU Agathe, Agnès, Geneviève 43 2191 Monsieur BODELET Mathys, Ivan 44 25127 Monsieur DEMEY Pierre, François, Corneille 45 6989 Monsieur MANGONE Sébastien, Jean, Francesco 46 14099 Monsieur LOUVARD Enzo, Léo, Hugo 47 20290 Madame HEGRON Charlotte, Agathe 48 20509 Monsieur GAUDRON-DESJARDINS Antoine, Paul, Baptiste 49 17778 Monsieur CADET Antonin, Lucien, Aurélien 50 15528 Madame JEAN--MACTOUX Séléna, Justine 51 3033 Monsieur HATMI Bilel 52 36903 Madame DE MONTGOLFIER Inès, Iname 53 16880 Monsieur TYMINSKI- -PEREIRA Clément, Louis 54 3182 Monsieur BAALI Ilias 55 48474 Monsieur LE GUENNIC Yuan, Edwin 56 16075 Monsieur VALETTE Lino, Bruce, Tancrède 57 5574 Monsieur FAVIN-LÉVÊQUE Tanguy, Louis, Bernard 58 28886 Monsieur COURANT Clément, Louis, Takumi 59 15349 Monsieur TEROUANNE Cyprien, Justin, Christophe 60 26549 Monsieur TEINTURIER Arnaud 61 5798 Monsieur RICHE Arthur, Jean, Alain 62 14480 Madame RENAUD Marion, Claire, Chloé 63 40822 Monsieur POTTIER Julien, Alexandre, Léonard 64 24104 Madame TERNOIS Alice, Sophie, Stéphanie 65 2960 Monsieur LÉPICIER Damien, Jean-Max, André 66 1875 Monsieur DODEL Marc, Philippe Marie 67 21178 Monsieur -

No Solutions for Water-Short Area

Property of the Watertown Historical Society watertownhistoricalsociety.org Timely Coverage Of News in The Fastest Growing Community in Litehfield County Vol. 40 No. 32 SUBSCRIPTION PRICE $12.00 PER, YEAR Car. Rt. P.S. PRICE 30 CENTS August 8, 1985 v Developers Raising Dust Along Main ThoroughfareNo Solutions For Site plan renderings and specifications on, paper that went to town zoning officials last fall are bearing, fruition 'this summer through, a. host of noticeable building projects underway along Main Street. All of it has left Stanley Masayda, zoning enforcement officer, with Water-Short Area; the observation that "things sure are busy!" The largest excavation project occurring these days is next to Pizza Hut, where a large sloped lot almost has been brought down to street level. The project of Anthony Cocchiola and Raymond Brennan even- tually will see a two-story office building on the site. Wells Investigated Plans were submitted to and approved by the Planning and Zoning Residents of the Grandview and Nova Scotia Hill Pair Circuit Avenues area of town, came to Monday night's Town Council meeting hoping to find sonic solu- Lodge Park Complaints tions for their ongoing dilemma of living, without adequate .water. The vice chairman, of the Town, woman Barbara HyincI,. authoriz- ed Town Manager Robert Mid- The only cone I us ion reached was Council Monday night asked the at this moment there is none, and town manager to nave a full report daugh to look into the charges made by Joseph Zu rait is, 555 Nova officials still arc trying to come up prepared for a future Council with a plan. -

Sur La Répartition Des Coefficients Des Formes Modulaires De Poids Demi-Entier

Sur la répartition des coefficients des formes modulaires de poids demi-entier Corentin Darreye To cite this version: Corentin Darreye. Sur la répartition des coefficients des formes modulaires de poids demi-entier. Théorie des nombres [math.NT]. Université de Bordeaux, 2020. Français. NNT : 2020BORD0171. tel-03066273 HAL Id: tel-03066273 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03066273 Submitted on 15 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE PRÉSENTÉE À L’UNIVERSITÉ DE BORDEAUX ÉCOLE DOCTORALE DE MATHÉMATIQUES ET D’INFORMATIQUE par Corentin DARREYE POUR OBTENIR LE GRADE DE DOCTEUR SPÉCIALITÉ — MATHÉMATIQUES Sur la répartition des coefficients des formes modulaires de poids demi-entier Date de soutenance : 6 novembre 2020 Devant la commission d’examen composée de : Régis de la Bretèche Professeur, Université Paris Diderot, IMJ-PRG Examinateur Farrell Brumley Maître de Conférences, Université Sorbonne Paris Nord, LAGA Rapporteur Henri Cohen Professeur, Université de Bordeaux, IMB Examinateur Étienne Fouvry Professeur, Université Paris-Saclay, LMO Examinateur Florent Jouve Professeur, Université de Bordeaux, IMB Directeur Guillaume Ricotta Maître de Conférences, Université de Bordeaux, IMB Directeur Emmanuel Royer Professeur, Université Clermont Auvergne, LMBP Examinateur Jie Wu Chargé de Recherche, Université Paris-Est Créteil, LAMA Rapporteur Financement du M.E.S.R. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

The Legibility of Saint Anthony Church from an Architectural Perspective

Journal of the Faculty of Engineering and Architecture of Gazi University 35:3 (2020) 1499-1508 The Legibility of Saint Anthony Church from an Architectural Perspective Elif Atıcı1 , Mehmet İnceoğlu2 1Department of Architecture, Eskişehir Osmangazi University, Eskişehir, 26040, Turkey 2Department of Architecture, Eskişehir Technical University, Eskişehir, 26210, Turkey Highlights: Graphical/Tabular Abstract Legibility of the Religious spaces can be seen as a place where people can both experience their own spiritual feelings and architectural structure allow for some common sharing with other people in the community. The architectural elements that make up Communication of the the space shape the behavior of the user. The churches, which are regarded as the place of the Christian religion, architectural structure also reveal different connotations to its users with its architectural styles. The architectural style of the building with its user gives the building a character. This character guides the user's attitudes and attitudes. In this study, the St. The effect of Antuan Church in the Beyoğlu district, where Istanbul is home to many cultures, was examined. St. Antuan architectural education Church is a church with Neo-Gothic architecture and it is still open for use. In the scope of the study, the on perception survey method was applied. The reason for the application to architecture students; to see what changes occur in the perception of the structure as the level of education increases. The data obtained as a result of the survey Keywords: study were evaluated by SPSS analysis. St. Antuan Church and its legibility are shown in figure A. Saint Antoine Church Gothic Architecture Religion Perception Legibility Article Info: Research Article Received:01.07.2019 Accepted: 05.02.2020 DOI: 10.17341/gazimmfd.584836 Correspondence: Figure A. -

Roanoke County Police Department Outstanding Warrants List As of 08

Roanoke County Police Department Outstanding Warrants List as of 09/20/2021 Press the Ctrl, F keys to search by Last Name with Adobe Acrobat Reader's search feature or just scroll through the document. Name Sex Age Warrant Charge A Acros Lopez, Julio CeserMale 30 Felony By Prisoner Adams, Benjamin EarlMale 32 Fail To Appear On Misdemeanor Charge Adams, Jacqueline AFemale 37 Contributing To The Delinquency Of A Minor Adams, Jacqueline AFemale 37 False Report Of Crime To Police Aker, Ruthie Age Of Children Required To Attend School Albright, Katherine ElizabethFemale 30 Order Of Protection (Final) Aliff, James MaxwellMale 31 Revocation Of Suspension Of Sentence/Probation Alouf, Hollie HarrisFemale 49 Zoning Violation Al-Tamimi, Yassin KamelMale 21 Reckless Driving - General Amos, Tommie LeeMale 50 Order Of Protection (Final) Anderson, Chris AaronMale 30 Violation Of Stalking Protective Order Anderson, Rodney WestonMale 59 Contempt Of Court: Misbehavior In Court Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Possess, Transport Firearms, Ammunitions, Explosives By Convicted Felons Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Destruction Of Property, Monument <$1000 W/Int Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Credit Card Theft - From Building Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Assault & Battery -Family Member Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Petit Larceny: Building <$1000 Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Simple - Assault By Strangulation Argueta, Enso NoelMale 34 Fail To Appear On Misdemeanor Charge Armstrong, Sandra KayFemale 58 Fail To Appear On Misdemeanor Charge Arrington, Crystina JasmineFemale -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

Run Date: 08/30/21 12Th District Court Page

RUN DATE: 09/27/21 12TH DISTRICT COURT PAGE: 1 312 S. JACKSON STREET JACKSON MI 49201 OUTSTANDING WARRANTS DATE STATUS -WRNT WARRANT DT NAME CUR CHARGE C/M/F DOB 5/15/2018 ABBAS MIAN/ZAHEE OVER CMV V C 1/01/1961 9/03/2021 ABBEY STEVEN/JOH TEL/HARASS M 7/09/1990 9/11/2020 ABBOTT JESSICA/MA CS USE NAR M 3/03/1983 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DIST. PEAC M 11/04/1998 12/04/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA HOME INV 2 F 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DRUG PARAP M 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA TRESPASSIN M 11/04/1998 10/20/2017 ABERNATHY DAMIAN/DEN CITYDOMEST M 1/23/1990 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT SPD 1-5 OV C 8/23/1993 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT IMPR PLATE M 8/23/1993 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 8/04/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI OPERATING M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI REGISTRATI C 9/06/1968 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA DRUGPARAPH M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA USE MARIJ M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OWPD M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA IMPR PLATE M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SEAT BELT C 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON -

Official Directory of the European Union

ISSN 1831-6271 Regularly updated electronic version FY-WW-12-001-EN-C in 23 languages whoiswho.europa.eu EUROPEAN UNION EUROPEAN UNION Online services offered by the Publications Office eur-lex.europa.eu • EU law bookshop.europa.eu • EU publications OFFICIAL DIRECTORY ted.europa.eu • Public procurement 2012 cordis.europa.eu • Research and development EN OF THE EUROPEAN UNION BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑ∆Α • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND -

OMUN – 2Nd Record – Tribute to the Fall

ÓMUN 2019 • NEW ALBUM « TRIBUTE TO THE FALL » WITH www.atelierhurf.net Pascal Charrier: guitar MMXVIII Julien Tamisier: keyboards, electronics Yannis Frier Yannis Philippe Lemoine: tenor saxophone > DESIGN Teun Verbruggen: drumkit, electronics GRAPHIC www.nainoprod.com ÓMUN 1 ÓMUN brings together four musicians from the European contemporary jazz and improvised music scenes: Pascal Charrier (guitar), Julien Tamisier (keyboards, electronics), Philippe Lemoine (tenor saxophone) and Teun Verbruggen (drumkit, electronics). The quartet’s sound is a combination of timbres and resonances. Every kind of approach is taken in a mixture of acoustic, electric, uncommon instrumental sounds as well as electronic and electroacoustic treatment of various sound sources. Dramatic generation of material and soundscapes disrupt bearings and invent a instantaneous poetry through processing, deconstruction and distortion. The listener navigates through a sea of reminiscences, guided by fragments of melodies like the residues of a collective memory. With this new repertory, the music places sound matter at the centre of the drama, questioning notions of permanence (emotions, bodies, ideas) and time (perpetual movement, spirals, abysses). The traditional stage/audience layout is also questioned with the creation of a circular common ground which gives both performers and audience the possibility to move around, thus changing their visual and auditive perception. This project is also pushed forward in the quintet version of the show called ÓMUN-IMAGE, in which -

Addressing the Challenge of High-Priced Prescription Drugs In

OVERVIEW Addressing the challenge of high-priced prescription drugs in the era of precision medicine: A systematic review of drug life cycles, therapeutic drug markets and regulatory frameworks Toon van der Gronde1, Carin A. Uyl-de Groot2, Toine Pieters1* a1111111111 a1111111111 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences (UIPS), Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands, 2 Institute for Medical Technology Assessment, Department of Health a1111111111 Policy & Management, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Citation: Gronde Tvd, Uyl-de Groot CA, Pieters T (2017) Addressing the challenge of high-priced Context prescription drugs in the era of precision medicine: Recent public outcry has highlighted the rising cost of prescription drugs worldwide, which in A systematic review of drug life cycles, therapeutic several disease areas outpaces other health care expenditures and results in a suboptimal drug markets and regulatory frameworks. PLoS ONE 12(8): e0182613. https://doi.org/10.1371/ global availability of essential medicines. journal.pone.0182613 Editor: Cathy Mihalopoulos, Deakin University, Method AUSTRALIA A systematic review of Pubmed, the Financial Times, the New York Times, the Wall Street Published: August 16, 2017 Journal and the Guardian was performed to identify articles related to the pricing of Copyright: © 2017 Gronde et al. This is an open medicines. access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and Findings reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Changes in drug life cycles have dramatically affected patent medicine markets, which have Data Availability Statement: All relevant data are long been considered a self-evident and self-sustainable source of income for highly profit- within the paper and its supporting information able drug companies. -

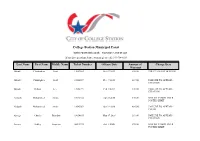

CS Online Warrants

College Station Municipal Court Active warrants as of: 9/27/2021 12:00:06 AM If you have questions about a warrant please call (979)764-3683 Last Name First Name Middle Name Ticket Number Offense Date Amount of Charge Desc Warrant Abbott Christopher Scott 13023163 Oct 27 2013 674.00 THEFT 0-50 1ST OFFENSE Abbott Christopher Scott 13026519 Dec 7 2013 419.00 FAILURE TO APPEAR - CITATION Abbott Delmar Lee 13002797 Feb 4 2013 347.00 FAILURE TO APPEAR - CITATION Abdouh Mohammed Amine 18033482 Apr 24 2018 178.00 SPEED 1-15 MPH OVER POSTED LIMIT Abdouh Mohammed Amine 18045052 Oct 22 2018 485.00 FAILURE TO APPEAR - COURT Abrego Charlie Brandon 18034895 May 17 2018 319.00 FAILURE TO APPEAR - CITATION Acosta Ashley Jaqueline 20011572 Oct 9 2020 278.00 SPEED 1-15 MPH OVER POSTED LIMIT Adame Jesse Louis 19004124 Mar 9 2019 629.00 CITY ORD PUBLIC URINATION Adams Lorenzo Tasheem 18035700 May 30 2018 412.00 SPEED 1-15 MPH OVER POSTED LIMIT Adams Shawn Lea 13016273 Aug 13 2013 347.00 FAILURE TO APPEAR - CITATION Adams Tray Robert 19007053 Apr 22 2019 349.00 FAILURE TO APPEAR - CITATION Aguilar Luis 17003820 Feb 16 2017 319.00 FAILURE TO APPEAR - CITATION Aguilar Salazar Gustavo 14002674 Feb 6 2014 319.00 FAILURE TO APPEAR - CITATION Aguilar Salazar Gustavo 14002675 Feb 6 2014 319.00 FAILURE TO APPEAR - CITATION Aguilera Jesse 15018647 Sep 19 2015 629.00 DISORDERLY CONDUCT FIGHTING Aguilera Nixon 17011771 Jun 9 2017 319.00 FAILURE TO APPEAR - CITATION Aguilera Nixon 17011773 Jun 9 2017 319.00 FAILURE TO APPEAR - CITATION Aguinaga Peggy Ann 17026389 Dec