Exploration of Potential Reservoir Hosts and Vectors Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Ecology of Lutzomyia Longipalpis and Lutzomyia Migonei

Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária ISSN: 0103-846X [email protected] Colégio Brasileiro de Parasitologia Veterinária Brasil Albuquerque Silva, Rafaella; Kassio Moura Santos, Fabricio; Caranha de Sousa, Lindemberg; Ferreira Rangel, Elizabeth; Leal Bevilaqua, Claudia Maria Ecology of Lutzomyia longipalpis and Lutzomyia migonei in an endemic area for visceral leishmaniasis Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária, vol. 23, núm. 3, julio-septiembre, 2014, pp. 320-327 Colégio Brasileiro de Parasitologia Veterinária Jaboticabal, Brasil Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=397841493005 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Original Article Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol., Jaboticabal, v. 23, n. 3, p. 320-327, jul.-set. 2014 ISSN 0103-846X (Print) / ISSN 1984-2961 (Electronic) Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014068 Ecology of Lutzomyia longipalpis and Lutzomyia migonei in an endemic area for visceral leishmaniasis Ecologia de Lutzomyia longipalpis e Lutzomyia migonei em uma área endêmica para Leishmaniose Visceral Rafaella Albuquerque Silva1,2; Fabricio Kassio Moura Santos1; Lindemberg Caranha de Sousa1; Elizabeth Ferreira Rangel3; Claudia Maria Leal Bevilaqua2* 1Núcleo de Controle de Vetores, Secretaria da Saúde do Estado do Ceará, Fortaleza, CE, Brasil 2Laboratório de Doenças Parasitárias, Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências Veterinárias, Universidade Estadual do Ceará – UECE, Fortaleza, CE, Brasil 3Laboratório de Transmissores das Leishmanioses, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil Received March 26, 2014 Accepted May 22, 2014 Abstract The main vector for visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in Brazil is Lutzomyia longipalpis. -

Of Lutzomyia Longipalpis (Diptera

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/261297; this version posted February 7, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Prediction of the secundary structure at the tRNASer (UCN) of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae) Richard Hoyos-Lopez _____________________ Grupo de Investigación en Resistencia Bacteriana y Enfermedades Tropicales, Universidad del Sinú, Montería, Colombia. Abstract. Lutzomyia longipalpis is the main vector of Leishmania infantum, the etiological agent of visceral leishmaniasis in America and Colombia. Taxonomically belongs to the subgenus Lutzomyia, which includes other vector species that exhibit high morphological similarity to the female species difficult to identify vectors in leishmaniasis foci and suggesting the search for molecular markers that facilitate this task, further researchs with mitochondrial genes, chromosome banding, reproductive isolation and pheromones evidence the existence of species complex. The aim of this study was to predict the secondary structure of mitochondrial transfer RNA serine (tRNASer) for UCN codon of Lutzomyia longipalpis as molecular marker for identify of this species. Sequences recorded in Genbank of L. longipalpis sequences were aligned with tRNA's from previously described species and then tRNASer secondary structure was inferred by software tRNAscan-SE 1.21. The length of tRNASer was 67 base pairs (bp). Two haplotypes were detected in the five sequences analyzed. The L. longipalpis tRNASer showed 7 intrachain pairing in the acceptor arm, 3 in the DHU arm, 4 in the anticodon arm and 5 in the TψC. -

REPÚBLICA DE NICARAGUA a W MINISTERIO DE TRANSPORTE E INFRAESTRUCTURA DIVISIÓN GENERAL DE PLANIFICACIÓN G N

000 000 000 000 000 000 810 820 830 840 850 860 Lugar El Papel g n a h s a w REPÚBLICA DE NICARAGUA a W MINISTERIO DE TRANSPORTE E INFRAESTRUCTURA DIVISIÓN GENERAL DE PLANIFICACIÓN g n a h s MAPA MUNICIPAL DE KUKRA HILL a w a Pueblo Nuevo RED VIAL INVENTARIADA POR TIPO DE SUPERFICIE W (Wawashang) o EE ll TToo rr tt uu gg uu ee rr oo MÎarshall Point 0 0 0 0 0 Orinoco Muelle 0 0 Comunal 0 9 Î 9 3 3 1 Muelle 1 Comunal Justo Point San Vicente La Unión Comarca El Toro Î Muelle Comunal La Fe San José cas 0 Bo 0 0 s 0 0 Do 0 0 0 8 8 3 3 1 1 i r Brown Bank a Î Pounla Lugar Larga N Muelle vista Comunal Martin Holm Brown Bank Pandler LL aa gg uu nn aa dd ee Dos Bocas PP ee rr ll aa ss Santa Rita Kakabila Î Muelle Comunal D 0 0 0 o 0 0 s 0 B Isla Hog Cay 0 oc 0 7 a (El Puerco) 7 3 s 3 1 1 Lomas Piedras Gordas Lugar Casaba Comarca La Nari Arenitas II Pichinga Î El Caimito Raitipura Muelle Municipal LAGUNA DE PERLAS Altamira Punta Rocky Awas Kama Point Bila Point Centros Castellon Haulover El Panchón Î Muelle Comunal Punta Harrys KK uu kk rr aa HH ii ll ll Point El Escobal Manhattan Centros El Centros de El Cacao Zancudo San Isidro El Pachon El Almendro 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 Casa Blanca 6 3 349 3 1 ¤£ San Lorenzo 1 Samuel Lau Flor de Pino ¤£358 Las Delicias El Zapote Lugar El Guari El Salto La Palma (Palma Carlos Fonseca EE ll RR aa mm aa Africana) La Fonseca Tierra Dorada 330 (Rio ¤£ Los Gaitanes Centros de Kama Kama) Big Lagoon KUKRA HILL Centros El Las Lapas Las Limas Î Muelle Comunal Machete San Ramon ¤£364 ¤£310 El Encanto Î Los Ruíz San Antonio -

Genetic Evidence for a Tacaribe Serocomplex Virus, Mexico

blood, samples of kidney and other solid tissues, and the Genetic Evidence skins and skeletons of the rodents were deposited into the Museum of Texas Tech University. for a Tacaribe The blood samples were tested by ELISA (10) for anti- body (immunoglobulin [Ig] G) to Whitewater Arroyo virus Serocomplex strain AV 9310135 (7). Samples of spleen and kidney from white-toothed woodrats TK133448 and TK133451, 7 oth- Virus, Mexico er white-toothed woodrats, 2 antibody-positive Nelson’s Catherine C. Inizan, Maria N. B. Cajimat, pocket mice (Chaetodipus nelsoni), and an antibody-pos- Mary Louise Milazzo, Artemio Barragán-Gomez, itive Merriam’s kangaroo rat (Dipodomys merriami) were Robert D. Bradley, and Charles F. Fulhorst tested for arenavirus by cultivation in monolayers of Vero E6 cells (11). Samples of kidney from the antibody-positive We isolated arenavirus RNA from white-toothed wood- rodents were tested for arenavirus RNA by using hemin- rats (Neotoma leucodon) captured in a region of Mexico in ested PCR assays. The fi rst-strand cDNA for the PCR was which woodrats are food for humans. Analyses of nucleotide synthesized by using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase and amino acid sequence data indicated that the woodrats were infected with a novel Tacaribe serocomplex virus, pro- (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) posed name Real de Catorce virus. in conjunction with oligont 19C-cons (2). The nucleotide sequence alignments were analyzed by using MRBAYES 3.1.2 (12) in the computer software package PAUP*, ver- he Tacaribe serocomplex (family Arenaviridae, ge- sion 4.0b10 (http://paup.csit.fsu.edu). -

*For More Information, Please See

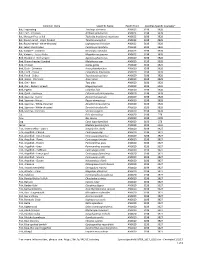

Common Name Scientific Name Health Point Specifies-Specific Course(s)* Bat, Frog-eating Trachops cirrhosus AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Fruit - Jamaican Artibeus jamaicensis AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Mexican Free-tailed Tadarida brasiliensis mexicana AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Round-eared - stripe-headed Tonatia saurophila AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Round-eared - white-throated Lophostoma silvicolum AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Seba's short-tailed Carollia perspicillata AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Vampire - Common Desmodus rotundus AN0023 3198 3928 Bat, Vampire - Lesser False Megaderma spasma AN0023 3198 3928 Bird, Blackbird - Red-winged Agelaius phoeniceus AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Brown-headed Cowbird Molothurus ater AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Chicken Gallus gallus AN0020 3198 3529 Bird, Duck - Domestic Anas platyrhynchos AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Finch - House Carpodacus mexicanus AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Finch - Zebra Taeniopygia guttata AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Goose - Domestic Anser anser AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Owl - Barn Tyto alba AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Owl - Eastern Screech Megascops asio AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Pigeon Columba livia AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Quail - Japanese Coturnix coturnix japonica AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - Harris' Zonotrichia querula AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - House Passer domesticus AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - White-crowned Zonotrichia leucophrys AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Sparrow - White-throated Zonotrichia albicollis AN0020 3198 3928 Bird, Starling - Common Sturnus vulgaris AN0020 3198 3928 Cat Felis domesticus AN0020 3198 279 Cow Bos taurus -

QUEREMOS Testimonios De Violencia Contra Las Mujeres En El Caribe Sur De Nicaragua Créditos

Vivas las QUEREMOS Testimonios de violencia contra las mujeres en el Caribe Sur de Nicaragua Créditos Coordinación: Mara Martínez Cruz, Global Communities Investigación: Martha Flores Fotografías: Margarita Montealegre Morales Edición de texto: Tania Montenegro Rayo Tratamiento digital fotográfico: Douglas López Toledo Diseño gráfico: Marlon Pérez Armas • [email protected] Esta publicación es posible gracias al generoso apoyo del pueblo estadounidense a través de la Agencia de los Estados Unidos para el Desarrollo Internacional (USAID). El contenido de esta obra es responsabilidad exclusiva de Global Communities y no refleja necesariamente las opiniones de USAID o del Gobierno de los Estados Unidos. A las vidas de Ena María, Fátima, Gioconda, Juana Marcelina, Jenery, Jessenia, Julia, Luz Marina, Marileth, Marling, Marlene, Melania, Paula, Petronila, Rosibel, Tatiana, Xiomara, Zayra... y de todas aquellas que también tenían sueños. Presentación La exposición fotográfica “Vivas nos queremos” • Testimonios de violencia contra las mujeres en el Caribe Sur de Nicaragua, presenta los rostros e historias de 18 mujeres víctimas de femicidio o de violencia letal entre el 2014 y el 2016 en la Región Autónoma Costa Caribe Sur, de acuerdo a los registros del monitoreo del sitio Voces contra la Violencia: www.voces.org.ni. El lente de la fotoperiodista Margarita Montealegre y los testimonios recogidos por la activista Martha Flores, captan imágenes extraídas de los álbumes familiares, objetos personales y espacios, además de los rostros de personas cercanas que comparten sus recuerdos para describir cómo eran ellas, la forma en que murieron y si se ha hecho o no justicia. Estos relatos visuales y testimoniales buscan contribuir a sensibilizar a nivel personal y colectivo sobre el impacto que tiene la violencia contra las mujeres en sus vidas y en la sociedad. -

REPÚBLICA DE NICARAGUA 500 700 900 580 600 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 MINISTERIO DE TRANSPORTE E INFRAESTRUCTURA 0 0 0 Honduras 0 4 4 0 0 3 M a N a G U a 3 0 0

000 000 000 000 000 000 000 585 590 595 600 605 610 615 T ii p ii tt a p a San Las Casitas Los MAPAS DE LOCALIZACIÓN MANAGUA Luis Zambrano 000 000 000 000 000 REPÚBLICA DE NICARAGUA 500 700 900 580 600 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 MINISTERIO DE TRANSPORTE E INFRAESTRUCTURA 0 0 0 Honduras 0 4 4 0 0 3 M A N A G U A 3 0 0 1 M A N A G U A 1 6 6 DIVISIÓN GENERAL DE PLANIFICACIÓN 1 1 RRAACCCC NN 0 0 0 0 0 0 Cofradia JJIINNOOTTEE GGAA 0 o 0 N U E V A MAPA MUNICIPAL DE MASAYA N U E V A 4 4 SSEEGGOOVVIIAA 3 3 M A D R I Z 1 RED VIAL INVENTARIADA POR TIPO DE SUPERFICIE 1 M A D R I Z EESSTTEELL II M a ss a y a 0 0 El Plantel 0 M A T A G A L P A 0 0 CCHHIINNAA NNDDEE GGAA M A T A G A L P A 0 0 0 0 0 RRAACCCC SS 0 0 0 0 LLEEOONN 0 M AASSAAYYAA 0 4 4 B O A C O 0 0 1 B O A C O 1 2 2 3 3 M a n a g u a 1 1 MMAANNAA GGUUAA CCHHOONNTTAALLEESS MMAASSAAYYAA El Papayal C A R A Z O C A R A Z O RRIIOO SSAA NN GGRRAANN AADDAA JJUUAANN Laguna de Tisma RRIIVVAASS Mar Océano Caribe 0 0 0 Pacífico 0 0 0 C A R A Z O G R A N A D A 0 0 C A R A Z O G R A N A D A 0 0 2 2 Nancitepe 1 Costa Rica 1 Monte T ii s m a 500000 700000 900000 580000 600000 Cristo TISMA San Veracruz Juaquin MACROLOCALIZACIÓN MICROLOCALIZACIÓN 0 0 0 Las 0 0 0 5 Valle Gothel Mercedes 5 3 3 3 3 1 Guanacastillo 1 Los Miravalle Bosque Vanegas INFORMACIÓN DEL MUNICIPIO Chacocente Las Lomas El Portillo Tipo de Superficie Clasificación Funcional La Joya Eucalipto KILÓMETROS KILÓMETROS Madrigales Campo Real El Ceibal Maltidina TIPO CLASIFICACIÓN (KM) (KM) Cuatro Norte Las El volcan Piedra Menuda Esquinas Brisas Alfonso -

Fifth Year Work Plan Cooperative Agreement No.: AID-524-A-10-00003

Fifth Year Work Plan Cooperative Agreement No.: AID-524-A-10-00003 Performance Period: October 1, 2014 - September 30, 2015 August 2014 The views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 1 Contents 1. Executive summary ............................................................................................................................... 5 2. Demographic and HIV statistics. ......................................................................................................... 11 2.1 HIV statistics generated by MoH ...................................................................................................... 11 2.2 HIV statistics by seroprevalence studies (CDC, GF, Others) .............................................................. 12 2.3 HVI statistics generated by PrevenSida ............................................................................................ 12 2.4 Estimated coverage for key population ............................................................................................ 13 3. Description and background of the HIV implementing mechanism in the country ........................... 13 4. Programs goals and strategic components within the PERFAR framework ....................................... 14 1. Technical Report ................................................................................................................................. 15 1.1 Overview of Approach ................................................................................................................... -

REPÚBLICA DE NICARAGUA Palo Monte Redondo El Falcon Los Chiqueritos Blanco Arriba 0 0 REPUBLICA 0 0 0 0

000 000 000 000 515 520 525 530 El Falcon Valle El MAPAS DE LOCALIZACIÓN Roble El Jicaro Los Corintos 500000 700000 900000 450000 500000 El Mamey REPÚBLICA DE NICARAGUA Palo Monte Redondo El Falcon Los Chiqueritos Blanco Arriba 0 0 REPUBLICA 0 0 0 0 MINISTERIO DE TRANSPORTE E INFRAESTRUCTURA 0 0 0 0 El Mamey 0 0 0 0 0 0 DE HONDURAS E S T E L II 0 0 Monte Redondo 6 6 5 5 1 1 DIVISIÓN GENERAL DE PLANIFICACIÓN Honduras 4 4 SAN PEDRO 1 1 El Porvenir RRAA AA NN SS aann le DEL NORTE u o N U E V A sa MAPA MUNICIPAL DE SAN FRANCISCO DEL NORTE N U E V A J I N O T E G A FF rraann cciiss ccoo a 241 J I N O T E G A u El Cortezal ¤£ SS EE GGOOVV IIAA G dd eell N oorrtt ee RED VPIasAo CLab aIllNo VENTARIADA POR TIPO DE SUPERFICIE El Tamarindo MMAA DD RRII ZZ El Cortezal G Loma Alma Los Hornitos u EE SS TTEE LL II as El Tamarindo El Lajero S a n P e d rr o Agua Buena a u 0 M A T A G A L P A 0 le 0 M A T A G A L P A 0 0 C H I N A N D E G A 0 La Los C H I N A N D E G A C H I N A N D E G A 0 0 C H I N A N D E G A d e ll N o rr tt e RRAA AA SS Unión La Union Aguacates 0 0 0 0 4 L E O N 4 El Paraíso L E O N 0 0 1 B O A C O 1 B O A C O 0 0 Plan Grande 0 0 Palo Blanco 0 0 El Coyolito Plan Grande El G uasimo S a n 4 4 MMAA SSAAYYAA 1 1 La Unión Los Aguacates CCHH OONN TTAA LLEE SS Agua Buena MMAA NN AAGG UUAA Polvazón Guásimo J o s é El Alto La Unión El Porvenir El Coyolito CCAA RR AAZZ OO L E O N El Asentamiento OCEANO El Chaparral d e C u s m a p a Al Naranjo GGRRAA NN AA DDAA Mar El Alto PACIFICO Jocomico Caribe Loma de El Chaparral El Cebollal El Polvazon -

Plan De Manejo De La Reserva Natural Volcán Mombacho

Fundación Cocibolca Fundación Nicaragüense para la Conservación Ministerio del Ambiente y los Recursos Naturales MARENA DIRECCION GENERAL DE PATRIMONIO NATURAL DIRECCIÓN DE MANEJO INTEGRAL PROMOCIÓN Y DESARROLLO DEL SINAP Octubre 2017 CONTENIDO A- LISTA DE TABLAS .............................................................................................................................. 7 Tabla 1. Categorías de uso del suelo en la Reserva Natural Volcán Mombacho ............................ 34 Tabla 2. Categorías de uso del suelo en la Zona de Amortiguamiento Reserva Natural Volcán Mombacho ...................................................................................................................................... 35 Tabla No. 3 Registros de Vida Silvestre de la Reserva Natural Volcán Mombacho ........................ 55 Tabla 4. Protagonistas locales presentes en el área protegida ...................................................... 69 Tabla 5.- Criterios para valoración de objetos de conservación del Area Protegida ...................... 73 Tabla 6.- Valoración de la Fauna de la Reserva Natural Volcán Mombacho .................................. 74 Tabla 7.- Valoración de las especies de Flora de la RNVM. ............................................................ 74 Tabla 8.- Valoración del Paisaje de la RNVM (Paisajes dentro y visibles desde el Área Protegida). ...................................................................................................................................... 75 Tabla 9. Matriz para valorar -

República De Nicaragua

000 000 000 000 000 000 710 720 730 740 750 760 G La Esperanza R San Luis MM aa tt ii gg uu áá ss A E N A La Esperanza Santa Tereza D P MAPAS DE LOCALIZACIÓN D LL aa CC rr uu zz E L S La Bodega E A E A Las Minitas A Santa Aurora El Corozo W D D N 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 P I D dd ee RR íí oo E G 500 700 900 700 750 800 850 900 San Emilio N R L A U La Bodega E M A A S K A T A San Francisco D R La Ceiba G r a n d e G T Las Cruces G r a n d e A A W N REPÚBLIGCA DE NICARAGUA N A G M El Carmen I RR AA CC CC NN A T A Providencia Santa Fé R U A L R Dolorito AS P San Antonio K W 0 IN 0 0 A 0 G M R 0 0 0 San Juan KU 0 Lomas de 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 MINISTERIO DE TRANSPORTE E INFRAESTRUCTURA 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 San Ramón Calzón Quemado 1 5 5 Isabel 0 0 4 4 4 4 La Esperanza 0 0 1 La Feria 1 San Jerónimo 1 1 PP aa ii ww aa ss 6 6 MM AATTAA GG AA LL PPAA DIVISIÓN GENERAL DE PLANIFICACIÓN 1 1 San Francisco El Jobo SONORA Honduras A E La Feria P D R A C C N E l A y o t e R A C C N E l A y o t e L 205 La Esperanza J I N O T E G A 0 0 San José J I N O T E G A 0 0 E ¤£ A Santa Ana MAPA MUNICIPAL DE EL AYOTE Las Mercedes AS 0 0 D El Cacao W 0 0 G IN N U E V A S E G O V I A R N U E V A S E G O V I A 0 0 N Vulla Sigula San Luis A U San José K 4 4 A T San Emilio 1 1 A R Santa Maria RED VIAL INVENTARIADA POR TIPO DE SUPERFICIE MMAADDRRIIZZ M G La Maravilla BB OO AA CC OO El Trapiche San Antonio San Pedro San José EESSTTEELLII San Jose 0 0 0 0 o 0 0 El Amparo El Garrobo 0 R A C C S 0 0 MMAATTAAGGAALLPPAA 0 R A C C S 5 5 0 0 Las Delicias 0 0 Los Flores CCHHIINNAANNDDEEGG AA 3 3 0 0 San Ramón R A C C S 1 1 0 R A C C S 0 San Antonio 4 LLEE OONN 4 CC HH OO NN TTAA LL EE SS San Isidro Las Canarias 1 1 Mar San Jose I San Jose I El Zopilote BBOO AACCOO Caribe 0 0 0 0 Veracruz San Ramón Santa Faz El Espejo CCHHOONNTTAALLEESS 0 0 San Francisco MMAANNAAGGUUAA 0 0 Luminanza 0 0 MMAASSAAYYAA 3 3 San Fernando CCAARRAAZZOO 1 1 GGRRAANNAADDAA Océano Mar San Juan Santa Cecilia RRIIVVAASS F. -

Nicaragua Strategic Alliances for Social Investment Alliances2 Para La Educación Y La Salud Systematization Report

Nicaragua Strategic Alliances for Social Investment Alliances2 para la Educación y la Salud Systematization Report February 28, 2014 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by RTI International. Nicaragua/Strategic Alliances for Social Investment Alliances2 para la Educación y la Salud Systematization Report Cooperative Agreement 520-A-00-10-00031-00 Prepared for Alicia Slate, AOR U.S. Agency for International Development/Nicaragua Prepared by RTI International 3040 Cornwallis Road Post Office Box 12194 Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-2194 RTI International is one of the world's leading research institutes, dedicated to improving the human condition by turning knowledge into practice. Our staff of more than 3,700 provides research and technical services to governments and businesses in more than 75 countries in the areas of health and pharmaceuticals, education and training, surveys and statistics, advanced technology, international development, economic and social policy, energy and the environment, and laboratory testing and chemical analysis. RTI International is a trade name of Research Triangle Institute. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government (USG). Table of Contents Page Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................