Decrease in Pulmonary Function and Oxygenation After Lung Resection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nonintubated Thoracoscopic Surgery Using Regional Anesthesia and Vagal Block and Targeted Sedation

Original Article Nonintubated thoracoscopic surgery using regional anesthesia and vagal block and targeted sedation Ke-Cheng Chen1,2, Ya-Jung Cheng3, Ming-Hui Hung3, Yu-Ding Tseng1, Jin-Shing Chen1,2 1Department of Surgery, National Taiwan University Hospital Yun-Lin Branch, Yun-Lin County, Taiwan; 2Division of Thoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, National Taiwan University Hospital and National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan; 3Department of Anesthesiology, National Taiwan University Hospital and National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan Corresponding to: Dr. Jin-Shing Chen. Department of Surgery, National Taiwan University Hospital, No. 7, Chung Shan South Road, Taipei, Taiwan. Email: [email protected]. Objective: Thoracoscopic surgery without endotracheal intubation is a novel technique for diagnosis and treatment of thoracic diseases. This study reported the experience of nonintubated thoracoscopic surgery in a tertiary medical center in Taiwan. Methods: From August 2009 through August 2013, 446 consecutive patients with lung or pleural diseases were treated by nonintubated thoracoscopic surgery. Regional anesthesia was achieved by thoracic epidural anesthesia or internal intercostal blockade. Targeted sedation was performed with propofol infusion to achieve a bispectral index value between 40 and 60. The demographic data and clinical outcomes were evaluated by retrospective chart review. Results: Thoracic epidural anesthesia was used in 290 patients (65.0%) while internal intercostal blockade was used in 156 patients (35.0%). The final diagnosis were primary lung cancer in 263 patients (59.0%), metastatic lung cancer in 38 (8.5%), benign lung tumor in 140 (31.4%), and pneumothorax in 5 (1.1%). The median anesthetic induction time was 30 minutes by thoracic epidural anesthesia and was 10 minutes by internal intercostal blockade. -

Your Lung Operation Booklet

1 AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS DIVISION OF EDUCATION SURGICAL PATIENT EDUCATION Table of Contents Welcome ...................................................................................1 Your Lungs ...............................................................................2 Lung Cancer ...........................................................................3 SURGICAL Understanding Your Operation ........................................4 PATIENT Preoperative Tests ................................................................5 EDUCATION Home Preparation ................................................................8 The Day of Your Operation ...............................................13 After Your Operation ..........................................................14 Your Recovery and Discharge .........................................17 When to Call Your Doctor .................................................19 Welcome You and your family are important members of the surgical team. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) “Your Lung Operation: Education for a Better Recovery” program will help you prepare for your operation and recovery. You and your family will know what to expect. You will learn how to work with your surgical team to ensure that you have the best surgical outcomes. COMPLETE THE “YOUR LUNG OPERATION” EDUCATION PROGRAM: Watch the DVD Read the booklet Review the Medication List and Quit Smoking Resources (inside front cover) Complete the Activity Log (inside front cover) Send us your evaluation after -

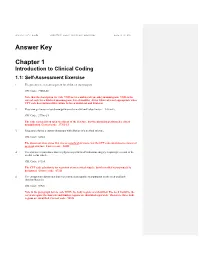

Answer Key Chapter 1

Instructor's Guide AC210610: Basic CPT/HCPCS Exercises Page 1 of 101 Answer Key Chapter 1 Introduction to Clinical Coding 1.1: Self-Assessment Exercise 1. The patient is seen as an outpatient for a bilateral mammogram. CPT Code: 77055-50 Note that the description for code 77055 is for a unilateral (one side) mammogram. 77056 is the correct code for a bilateral mammogram. Use of modifier -50 for bilateral is not appropriate when CPT code descriptions differentiate between unilateral and bilateral. 2. Physician performs a closed manipulation of a medial malleolus fracture—left ankle. CPT Code: 27766-LT The code represents an open treatment of the fracture, but the physician performed a closed manipulation. Correct code: 27762-LT 3. Surgeon performs a cystourethroscopy with dilation of a urethral stricture. CPT Code: 52341 The documentation states that it was a urethral stricture, but the CPT code identifies treatment of ureteral stricture. Correct code: 52281 4. The operative report states that the physician performed Strabismus surgery, requiring resection of the medial rectus muscle. CPT Code: 67314 The CPT code selection is for resection of one vertical muscle, but the medial rectus muscle is horizontal. Correct code: 67311 5. The chiropractor documents that he performed osteopathic manipulation on the neck and back (lumbar/thoracic). CPT Code: 98925 Note in the paragraph before code 98925, the body regions are identified. The neck would be the cervical region; the thoracic and lumbar regions are identified separately. Therefore, three body regions are identified. Correct code: 98926 Instructor's Guide AC210610: Basic CPT/HCPCS Exercises Page 2 of 101 6. -

Endoscopy Matrix

Endoscopy Matrix CPT Description of Endoscopy Diagnostic Therapeutic Code (Surgical) 31231 Nasal endoscopy, diagnostic, unilateral or bilateral (separate procedure) X 31233 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, diagnostic with maxillary sinusoscopy (via X inferior meatus or canine fossa puncture) 31235 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, diagnostic with sphenoid sinusoscopy (via X puncture of sphenoidal face or cannulation of ostium) 31237 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with biopsy, polypectomy or X debridement (separate procedure) 31238 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with control of hemorrhage X 31239 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with dacryocystorhinostomy X 31240 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with concha bullosa resection X 31241 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ligation of sphenopalatine artery X 31253 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ethmoidectomy, total (anterior X and posterior), including frontal sinus exploration, with removal of tissue from frontal sinus, when performed 31254 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ethmoidectomy, partial (anterior) X 31255 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ethmoidectomy, total (anterior X and posterior 31256 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with maxillary antrostomy X 31257 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ethmoidectomy, total (anterior X and posterior), including sphenoidotomy 31259 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with ethmoidectomy, total (anterior X and posterior), including sphenoidotomy, with removal of tissue from the sphenoid sinus 31267 Nasal/sinus endoscopy, surgical; with removal of -

Anesthesia for Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery

23 Anesthesia for Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery Edmond Cohen Historical Considerations of Video-Assisted Thoracoscopy ....................................... 331 Medical Thoracoscopy ................................................................................................. 332 Surgical Thoracoscopy ................................................................................................. 332 Anesthetic Management ............................................................................................... 334 Postoperative Pain Management .................................................................................. 338 Clinical Case Discussion .............................................................................................. 339 Key Points Jacobaeus Thoracoscopy, the introduction of an illuminated tube through a small incision made between the ribs, was • Limited options to treat hypoxemia during one-lung venti- first used in 1910 for the treatment of tuberculosis. In 1882 lation (OLV) compared to open thoracotomy. Continuous the tubercle bacillus was discovered by Koch, and Forlanini positive airway pressure (CPAP) interferes with surgi- observed that tuberculous cavities collapsed and healed after cal exposure during video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery patients developed a spontaneous pneumothorax. The tech- (VATS). nique of injecting approximately 200 cc of air under pressure • Priority on rapid and complete lung collapse. to create an artificial pneumothorax became a widely used • Possibility -

Anesthesia for Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery

Thoracic Anesthesia Can Be a Pleasure! Tips and Tricks For Maximizing Success Karen Sibert, MD Associate Clinical Professor Department of Anesthesiology & Perioperative Medicine David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA UCLA Health Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment in many areas of oncology, lung cancer remains a deadly disease and is the major source of the increasing caseload of thoracic surgery procedures today. A steadily increasing proportion of these cases are diagnosed in women. Complete surgical excision of tumor remains the only hope of cure. With more cardiac procedures moving from the OR to the cardiac catheterization laboratory, many cardiac surgeons are returning for fellowships in the burgeoning field of minimally invasive thoracic surgery. Only about 14% of lung carcinomas are of the small cell type; the remainder are squamous or adenocarcinomas which are operable if diagnosed early. Anesthesia for minimally invasive, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) is similar to anesthesia for open thoracic cases in many respects. However, achieving lung isolation quickly and completely is even more important, since even a slightly inflated lung may obstruct the surgeon’s view. Procedures that are amenable to VATS include: Mediastinoscopy Wedge resection or lung biopsy Lobectomy or segmentectomy Pleurodesis, mechanical or talc, for pleural effusion or spontaneous pneumothorax Decortication, including evacuation of empyema or hemothorax Lung volume reduction as treatment for severe emphysema. Any patient may be a candidate regardless of extremes of age or pulmonary disease. Procedures still requiring open thoracotomy include pneumonectomy, tracheal resection, and chest wall resection. The advantages of VATS include decreased hospital length of stay, decreased morbidity, and the ability to do more cases per day in each OR. -

A Guide to Thoracic Surgery for Patients and Families

A Guide to Thoracic Surgery for Patients and Families Section of Thoracic Surgery Department of Surgery Welcome to Michigan Medicine Your surgery is scheduled for: _______________________________________________ Your surgeon has given you a date and time for your operation. We make every effort to keep your surgery on the original date, however it may be postponed or rescheduled if unexpected delays happen. If this occurs, everything possible will be done to reschedule you to the earliest available date. We apologize for any inconvenience this may cause. Understanding Your Thoracic Surgery This teaching book has been designed to prepare you for thoracic surgery. It provides you and your family with useful information about your surgical journey, as well as care before and after surgery. Take your time reading each section of the book before your surgery. Bring this book to the hospital for your surgery. This book has been divided into chapters that walk you through what type of surgery will have and then through the process of your surgery and recovery. There are descriptions for each specific procedure starting on (page 8). Use the table of contents to find the page number describing your surgery. Having someone guide you from first evaluation to recovery makes it easier to understand the process of thoracic surgery and eases your stress knowing there is a friendly, familiar face you can count on. That person is your Clinical Care Coordinator (CCC). This nurse helps you navigate the system, get scheduled for tests, provides education about the process and makes sure you get to all the right places at the right time. -

Tracheal and Bronchial Surgery

Tracheal and Bronchial Surgery 1A031 Honorary Editors: Douglas E. Wood, Douglas J. Mathisen, Erino Angelo Rendina Editors: Xiaofei Li, Federico Venuta, David C. van der Zee Associate Editors: Dirk Van Raemdonck, Federico Rea, Jinbo Zhao Xiaofei Li, Federico Venuta, David C. van der Zee Xiaofei Li, Federico Venuta, Editors: Tracheal and Bronchial Surgery Honorary Editors: Douglas E. Wood, Douglas J. Mathisen, Erino Angelo Rendina Editors: Xiaofei Li, Federico Venuta, David C. van der Zee Associate Editors: Dirk Van Raemdonck, Federico Rea, Jinbo Zhao AME Publishing Company Room C 16F, Kings Wing Plaza 1, NO. 3 on Kwan Street, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong Information on this title: www.amegroups.com For more information, contact [email protected] Copyright © AME Publishing Company. All rights reserved. This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of AME Publishing Company. First published 2017 Printed in China by AME Publishing Company Editors: Xiaofei Li, Federico Venuta, David C. van der Zee Cover Image Illustrator: Zhijing Xu, Shanghai, China Tracheal and Bronchial Surgery Hardcover ISBN: 978-988-77841-8-0 AME Publishing Company, Hong Kong AME Publishing Company has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. The advice and opinions expressed in this book are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views or practices of AME Publishing Company. -

Canine Brachycephalic Airway Syndrome: Surgical Management

3 CE Credits Canine Brachycephalic Airway Syndrome: Surgical Management Michelle Trappler, VMD Kenneth W. Moore, DVM, DACVS Abstract: Many surgical options have been described to treat various aspects of canine brachycephalic airway syndrome (BAS). This article describes the surgical management, postoperative care, and prognosis of this condition. The pathophysiology and medical therapy of BAS are described in a companion article. For more information, please see the companion article, as a result of the tracheostomy procedure.3 Consequently, tracheos- “Canine Brachycephalic Airway Syndrome: Pathophysiology, tomy is only warranted in dogs that have complications during Diagnosis, and Nonsurgical Management” surgery and recovery.3,4 However, dogs undergoing surgical cor- rection of BAS abnormalities should be clipped for tracheostomy, arly intervention and correction of brachycephalic airway and the surgeon should be prepared to intervene if necessary.5 syndrome (BAS) abnormalities are recommended to halt Eprogression of airway pathology. For example, it has been Surgical Management suggested that dogs undergo surgical correction of stenotic nares The patient should be positioned in sternal recumbency with the at 3 to 4 months of age.1 Several surgical techniques exist to correct chin resting on a well-padded surface. The maxilla should be sus- various components of BAS. Tracheostomy is recommended for pended by rolled gauze or white tape hung between two IV poles patients with severe laryngeal collapse that does not respond to or similar structures. The mandible can also be secured to the table corrective surgical techniques. ventrally with white tape (FIGURE 1). The cuff of the endotracheal Preoperative Considerations Surgery should be performed in a facility with staff capable of monitoring for acute dyspnea and performing a tracheostomy in the immediate recovery peri- od because existing pathology and intraoperative trauma to airway tissues often results in dramatic and immediate post- operative swelling of the airway. -

The Open Anesthesia Journal

Send Orders for Reprints to [email protected] 49 The Open Anesthesia Journal Content list available at: www.benthamopen.com/TOATJ/ DOI: 10.2174/2589645801812010049, 2018, 12, 49-60 REVIEW ARTICLE Ventilation via Narrow-Bore Catheters: Clinical and Technical Perspectives on the Ventrain Ventilation System D. John Doyle1,2,* 1Department of General Anesthesiology, Cleveland Clinic, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates 2Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA Received: July 6, 2018 Revised: September 3, 2018 Accepted: September 4, 2018 Abstract: This brief review of the Ventrain ventilation system summarizes the main clinical and technical aspects of the device, with special emphasis on its role in the “Cannot Intubate, Cannot Oxygenate“ situation and in surgery involving the airway. Animal and bench studies characterizing the performance of the device, which is based on Bernoulli's Principle, are also discussed. It is concluded that as clinical experience is accumulated that this new device will play a special role in clinical airway management. Keywords: Ventrain, Jet ventilation, Transtracheal jet ventilation, Cannot Intubate, Cannot Oxygenate, Emergency airway management. 1. INTRODUCTION Mechanical ventilation of patients is usually carried out using a conventional diametere.g ( . 6 to 8 mm Internal Diameter [ID]) low-resistance cuffed tracheal tube inserted into the patient’s trachea. There are circumstances, however, where this arrangement is clinically unsuitable. For instance, with some forms of laryngeal surgery, a narrow-diameter high-resistance catheter (e.g. Hunsaker catheter) driven by a high-pressure gas source is used instead. This is done in order to offer the surgeon an unimpeded view of the glottic structures. -

Pulmonary Complications Following Lung Resection* a Comprehensive Analysis of Incidence and Possible Risk Factors

Pulmonary Complications Following Lung Resection* A Comprehensive Analysis of Incidence and Possible Risk Factors Franc¸ois Ste´phan, MD, PhD; Sophie Boucheseiche, MD; Judith Hollande, MD; Antoine Flahault, MD, PhD; Ali Cheffi, MD; Bernard Bazelly, MD; and Francis Bonnet, MD Study objectives: To assess the incidence and clinical implications of postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) after lung resection, and to identify possible associated risk factors. Design: Retrospective study. Setting: An 885-bed teaching hospital. Patients and methods: We reviewed all patients undergoing lung resection during a 3-year period. The following information was recorded: preoperative assessment (including pulmonary function tests), clinical parameters, and intraoperative and postoperative events. Pulmonary complications were noted according to a precise definition. The risk of PPCs associated with selected factors was evaluated using multiple logistic regression analysis to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Results: Two hundred sixty-six patients were studied (87 after pneumonectomy, 142 after lobectomy, and 37 after wedge resection). Sixty-eight patients (25%) experienced PPCs, and 20 patients (7.5%) died during the 30 days following the surgical procedure. An American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) score > 3 (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.07 to 4.16; p < 0.02), an operating time > 80 min (OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.09 to 3.97; p < 0.02), and the need for postoperative mechanical ventilation > 48 min (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.02 to 3.75; p < 0.04) were independent factors associated with the development of PPCs, which was, in turn, associated with an increased mortality rate and the length of ICU or surgical ward stay. -

Lung Wedge Resection, Pulmonary Metastasis (Metastasectomy)

Surgical Services: Thoracoscopy; Lung Wedge Resection, Pulmonary Metastasis (Metastasectomy) POLICY INITIATED: 06/30/2019 MOST RECENT REVIEW: 06/30/2019 POLICY # HH-5566 Overview Statement The purpose of these clinical guidelines is to assist healthcare professionals in selecting the medical service that may be appropriate and supported by evidence to improve patient outcomes. These clinical guidelines neither preempt clinical judgment of trained professionals nor advise anyone on how to practice medicine. The healthcare professionals are responsible for all clinical decisions based on their assessment. These clinical guidelines do not provide authorization, certification, explanation of benefits, or guarantee of payment, nor do they substitute for, or constitute, medical advice. Federal and State law, as well as member benefit contract language, including definitions and specific contract provisions/exclusions, take precedence over clinical guidelines and must be considered first when determining eligibility for coverage. All final determinations on coverage and payment are the responsibility of the health plan. Nothing contained within this document can be interpreted to mean otherwise. Medical information is constantly evolving, and HealthHelp reserves the right to review and update these clinical guidelines periodically. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without permission from HealthHelp. All