John Heminges and the Droitwich Shakespeare Connection the Discovery in St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Heminges's Tap-House at the Globe the Theatre Profession Has A

Untitled Document John Heminges's Tap-house at the Globe The theatre profession has a long association with catering and victualling. Richard Tarlton, the leading English comic actor of the late sixteenth century, ran a tavern in Gracechurch Street and an eating house in Paternoster Row (Nungezer 1929, 354); and W. J. Lawrence found a picture of Tarlton serving food to four merchants in his establishment (Lawrence 1937, 17-38). John Heminges, actor-manager in Shakespeare's company, appears to have continued the tradition by selling alcohol at a low-class establishment directly attached to the Globe playhouse. Known as a tap-house or ale-house, this kind of shop differed from the more prestigious inns and taverns in selling only beer and ale (no wine) and offering only the most basic food and accommodation (Clark 1983, 5). Presumably at the Globe most customers were expected to take their drinks into the playhouse. The hard evidence for Heminges's tap-house is incomplete and fragmented. Augustine Phillips, a King's man, died in May 1605 and his widow Anne married John Witter. Phillips's will designated Heminges as executor in the event of Anne's remarriage (Honigmann & Brock 1992, 74) and in this capacity Heminges leased the couple an interest in the Globe (Chambers 1923, 418; Wallace 1910, 319). When the Globe had to be rebuilt after the fire of 1613, the Witters could not afford their share and the ensuing case ("Witter versus Heminges and Condell" in the Court of Requests 1619-20) left valuable evidence about the organization of the playhouse syndicate. -

"A Sharers' Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical

Syme, Holger Schott. "A Sharers’ Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 33–51. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350051379.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 08:28 UTC. Copyright © Tiffany Stern and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 A Sharers’ Repertory Holger Schott Syme Without Philip Henslowe, we would know next to nothing about the kinds of repertories early modern London’s resident theatre companies offered to their audiences. As things stand, thanks to the existence of the manuscript commonly known as Henslowe’s Diary , scholars have been able to contemplate the long lists of receipts and expenses that record the titles of well over 200 plays, most of them now lost. The Diary gives us some sense of the richness and diversity of this repertory, of the rapid turnover of plays, and of the kinds of investments theatre companies made to mount new shows. It also names a plethora of actors and other professionals associated with the troupes at the Rose. But, because the records are a fi nancier’s and theatre owner’s, not those of a sharer in an acting company, they do not document how a group of actors decided which plays to stage, how they chose to alternate successful shows, or what they, as actors, were looking for in new commissions. -

Before the Beginning; After the End”: Stern, Tiffany

University of Birmingham “Before the Beginning; After the End”: Stern, Tiffany DOI: 10.1017/CBO9781139152259.023 License: Other (please provide link to licence statement Document Version Version created as part of publication process; publisher's layout; not normally made publicly available Citation for published version (Harvard): Stern, T 2015, “Before the Beginning; After the End”: When did Plays Start and Stop? in MJ Kidnie & S Massai (eds), Shakespeare and Textual Studies . Cambridge University Press, pp. 358-374. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139152259.023 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Shakespeares First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SHAKESPEARES FIRST FOLIO: FOUR CENTURIES OF AN ICONIC BOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Emma Smith | 400 pages | 15 Jun 2016 | Oxford University Press | 9780198754367 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Shakespeares First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book PDF Book Already have an account? The label Q n denotes the n th quarto edition of a play. The sheets were printed in 2-page formes, meaning that pages 1 and 12 of the first quire were printed simultaneously on one side of one sheet of paper which became the "outer" side ; then pages 2 and 11 were printed on the other side of the same sheet the "inner" side. Throughout, the stress is on what we can learn from individual copies now spread around the world about their eventful lives. Related Articles. It's hard to tell. A Shakespeare Companion — Stricter than, say, Bergen Evans or W3 "disinterested" means impartial — period , Strunk is in the last analysis whoops — "A bankrupt expression" a unique guide which means "without like or equal". Each copy has been part of many lives. And what did they do with them? Reader Writer Industry Professional. Korea national university of transportation. Jul 06, Michael P. Welcome back. It's a short but dense treatment of the topic and is focused on reading and readership, ownership, provenance, and what that says about how owners saw and treated the book. From the Book - First edition. Namespaces Article Talk. Loading Staff View. Glenn Crabtree rated it liked it Nov 25, The Foundations of Shakespeare's Text. Academic Skip to main content. The Passionate Pilgrim To the Queen. -

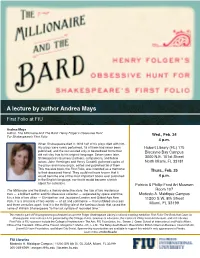

A Lecture by Author Andrea Mays First Folio at FIU

A lecture by author Andrea Mays First Folio at FIU Andrea Mays Author, The Millionaire And The Bard: Henry Folger’s Obsessive Hunt For Shakespeare’s First Folio Wed., Feb. 24 4 p.m. When Shakespeare died in 1616 half of his plays died with him. His plays were rarely performed, 18 of them had never been Hubert Library (HL) 175 published, and the rest existed only in bastardized forms that Biscayne Bay Campus did not stay true to his original language. Seven years later, Shakespeare’s business partners, companions, and fellow 3000 N.E. 151st Street actors, John Heminges and Henry Condell, gathered copies of North Miami, FL 33181 the plays and manuscripts, edited and published 36 of them. This massive book, the First Folio, was intended as a memorial to their deceased friend. They could not have known that it Thurs., Feb. 25 would become one of the most important books ever published 4 p.m. in the English language, nor that it would become a fetish object for collectors. Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum The Millionaire and the Bard is a literary detective story, the tale of two mysterious Room 107 men — a brilliant author and his obsessive collector — separated by space and time. Modesto A. Maidique Campus It is a tale of two cities — Elizabethan and Jacobean London and Gilded Age New 11200 S.W. 8th Street York. It is a chronicle of two worlds — of art and commerce — that unfolded an ocean and three centuries apart. And it is the thrilling tale of the luminous book that saved the Miami, FL 33199 name of William Shakespeare “to the last syllable of recorded time.” This event is part of FIU programming scheduled around the Folger Shakespeare Library’s national traveling exhibition First Folio! The Book that Gave Us Shakespeare. -

A Brief History of the Audience I Can Take Any Empty Space and Call It a Bare Stage

A Brief History of the Audience I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged. —Peter Brook, The Empty Space The nature of the audience has changed throughout history, evolving from a participatory crowd to a group of people sitting behind an imaginary line, silently observing the performers. The audience is continually growing and changing. There has always been a need for human beings to communicate their wants, needs, perceptions and disagreements to others. This need to communicate is the foundation of art and the foundation of theatre’s relationship to its audience. In the Beginning ended with what the Christians called “morally Theatre began as ritual, with tribal dances and inappropriate” dancing mimes, violent spectator sports festivals celebrating the harvest, marriages, gods, war such as gladiator fights, and the public executions for and basically any other event that warranted a party. which the Romans were famous. The Romans loved People all over the world congregated in villages. It violence, and the audience was a lively crowd. was a participatory kind of theatre, the performers Because theatre was free, it was enjoyed by people of would be joined by the villagers who believed that every social class. They were vocal, enjoyed hissing their lives depended on a successful celebration—the bad actors off the stage, and loved to watch criminals harvest had to be plentiful or the battle victorious, or meet large ferocious animals, and soon after, enjoyed simply to be in good graces with their god or gods. -

William Shakespeare 1 William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare 1 William Shakespeare William Shakespeare The Chandos portrait, artist and authenticity unconfirmed. National Portrait Gallery, London. Born Baptised 26 April 1564 (birth date unknown) Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England Died 23 April 1616 (aged 52) Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England Occupation Playwright, poet, actor Nationality English Period English Renaissance Spouse(s) Anne Hathaway (m. 1582–1616) Children • Susanna Hall • Hamnet Shakespeare • Judith Quiney Relative(s) • John Shakespeare (father) • Mary Shakespeare (mother) Signature William Shakespeare (26 April 1564 (baptised) – 23 April 1616)[1] was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist.[2] He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon".[3][4] His extant works, including some collaborations, consist of about 38 plays,[5] 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and a few other verses, the authorship of some of which is uncertain. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.[6] Shakespeare was born and brought up in Stratford-upon-Avon. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway, with whom he had three children: Susanna, and twins Hamnet and Judith. Between 1585 and 1592, he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part-owner of a playing company called the Lord Chamberlain's Men, later known as the King's Men. He appears to have retired to Stratford around 1613 at age 49, where he died three years later. -

Shakespeare Editions and Editors

Shakespeare Editions and Editors The 16th and 17th Centuries The earliest texts of William Shakespeare’s works were published during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in quarto or folio format. Folios are large, tall volumes; quartos are smaller, roughly half the size. Early Texts of Shakespeare’s Works: The Quartos and Bad Quartos (1594-1623) Of the thirty-six plays contained in the First Folio of 1623, eighteen have no other source. The eighteen other plays had been printed in separate and individual editions at least once between 1594 and 1623. Pericles (1609) and The Two Noble Kinsmen (1634) also appeared separately before their inclusions in folio collections. All of these were quarto editions, with one exception: the first edition of Henry VI, Part 3 was printed in octavo form in 1594. Popular plays like Henry IV, Part 1 and Pericles were reprinted in their quarto editions even after the First Folio appeared, sometimes more than once. But since the prefatory matter in the First Folio itself warns against the earlier texts, 18th and 19th century editors of Shakespeare tended to ignore the quarto texts in favor of the Folio. Gradually, however, it was recognized that the quarto texts varied widely among themselves; some much better than others. It was the bibliographer Alfred W. Pollard who originated the term “bad quarto” in 1909, to distinguish several texts that he judged significantly corrupt. He focused on four early quartos: Romeo and Juliet (1597), Henry V (1600), The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602), and Hamlet (1603). His reasons for citing these texts as “bad” were that they featured obvious errors, changes in word order, gaps in the sense of the text, jumbled printing of prose as verse and verse as prose, and similar problems. -

Isabel Vives, William Shakespeare's Mystery, the Theories About His

GRAU D’ESTUDIS ANGLESOS Treball de Fi de Grau Curs 2017-2018 WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S MYSTERY - THE THEORIES ABOUT HIS EXISTENCE - NOM DE L’ESTUDIANT: Isabel Vives Ginard NOM DEL TUTOR: Enric Montforte Rabascall Barcelona, 18 de juny de 2018 ABSTRACT William Shakespeare is known for being one of the most relevant writers in the history of English literature. His ability to write, his vocabulary and his knowledge of the world, among others, have made of his plays a treasure in the world’s literature of all times. His perfection in writing is precisely the reason why critics have questioned over time whether William Shakespeare was the real author of the plays attributed to him. Who was William Shakespeare? Or who was the author writing behind the name of William Shakespeare? Several Anti-Stratfordians, those who deny Shakespeare’s authorship, have suggested their candidates and have explained the reasons why they are totally plausible Shakespeares. Nonetheless, there are critics who remain faithful to the theory that William Shakespeare did exist and that the only real author of the plays attributed to him was Shakespeare himself. This paper focuses on these two points of view about William Shakespeare’s existence, trying to approach the truth about the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays. Key words: Shakespeare, authorship controversy, Anti-Stradfordians, Stratfordians RESUM William Shakespeare és conegut per ser un dels autors més rellevants de la història de la literatura anglesa. La seva habilitat en l’escriptura, el seu vocabulari i el seu coneixement del món, entre d’altres, han fet de les seves obres un tresor de la literatura universal de tots els temps. -

How Quickly Nature Falls Into Revolt on Revisiting Shakespeare’S Genres

How Quickly Nature Falls Into Revolt On Revisiting Shakespeare’s Genres By Mike Stumpf 13 When the first folio edition of William Shakespeare’s works kinds of genres, such as tragicomedy. In addition, Polonius’s the reader passes through the various perspectives was published in 1623, “it was not clear whose idea the speech in the second Quarto (Q2) of Hamlet, printed in offered by the text and relates the different views collected volume was or even what was the precise motivation 1604, emphasizes the variety of dramatic modes available and patterns to one another he sets the work in for it” (Proudfoot, Thompson, & Kastan-1998, 8), but the as he states the players at Elsinore as “the best actors in the motion, and so sets himself in motion too. (Iser- inclusion of two actors that worked with Shakespeare in the world, [for] either for Tragedie, Comedy, Hiftory, Paftorall, 1978, 21) publication process underscores the importance of accuracy Paftorall Comicall, [or] Hiftoricall Paftorall” (Hamlet-1985, of authorial intent in the volume. This is especially important II.ii.415-416). Thus, publications prior to F1 highlight the Iser’s theory proposes a dualistic relationship between the since the actors, John Heminges and Henry Condell, state availability of other genres to the F1 publishers. However, text and the reader where each has influence on the other. that while Shakespeare’s input would have been preferred, even though F1 was “publifhed according the True Originall However, this also subjects a work of literature to a certain set “he by death departed from that right, [and that] we pray Copies” (Moston-1998, 5), “Shakespeare himself does not of interpretational guidelines where one endpoint is authorial you do not envie his Friends, the office of their care, and seem to have undertaken to oversee the printing of his plays, intent and the other is any given reader’s perception of the paine to haue collected & publifh’d them. -

The Seven Deadly Sins</Em>

Early Theatre 7.1 (2004) David Kathman Reconsidering The Seven Deadly Sins Among the Henslowe-Alleyn papers at Dulwich College is a document long prized by theatre historians: the handwritten ‘plot’ of a play called The Second Part of the Seven Deadly Sins (Dulwich College MS XIX), apparently designed to be hung on a peg backstage at a playhouse. The text of this play does not survive, but it is usually thought to be identical with Richard Tarlton’s ‘famous play of the seauen Deadly sinnes’, referred to in 1592 by Gabriel Harvey and Thomas Nashe.1 The plot is extremely valuable for its scene-by-scene descrip- tion of the play’s action, which lists the characters and (most of) the players who played those characters in each scene. There are twenty players’ names in all: Mr. Brian, Mr. Phillipps, Mr. Pope, R. Burbadg, W. Sly, R. Cowly, John Duke, Ro. Pallant, John Sincler, Tho. Goodale, John Holland, T. Belt, Ro. Go., Harry, Kit, Vincent, Saunder, Nick, Ned, and Will. In addition, two major roles (King Henry VI and Lydgate) and several minor ones are not accompanied by any player’s name. Since this is the most complete cast list we have for any performance of a pre-restoration play, it has often been used as evidence in reconstructing the history of Elizabethan playing companies, as well as the careers of the individual players named therein.2 One problem is that the company which performed this play is nowhere named in the plot. For more than a century, most theatre historians have assumed that the company in question was some version of Lord Strange’s Men performing in the early 1590s. -

First Folio Fraud 69

Chiljan - First Folio Fraud 69 First Folio Fraud Katherine Chiljan n e of the greatest events in literary history was the publication of Mr William Shakespeare’s Histories Comedies and Tragedies in 1623. Today called the “First Fo lio,” the book contained thirty-six Shakespeare plays, twenty of which had Onever been printed. It was reissued nine years later, and two times after that. The first sixteen pages of the Folio – the preface – are extremely important to the Shakespeare professor because they contain his best evidence for the Stratford Man as the great author, so much so that had the First Folio never been published, few or none would have connected the great author with the Stratford Man. These preliminary pages, therefore, merit close and careful examination – what is said and what is not said. Prior to the First Folio, the great author’s person was undefined. “William Shakespeare” was only a name on title pages of his printed works or a name noted by literary critics regarding his works. This fostered the belief among some that the name was a pseudonym, and it seems that the First Folio preface tried to dispel that notion and to fill the personality void. William Shakespeare emerges in the opening pages as a person born with that name and a hint at his origins. He was a natural genius, the fellow of actors, and strictly a man of the theater. The “news” that he was dead was also given, but when or how long ago this had occurred remains obscure. On the surface, there seemed no reason to suspect the book.