Naval Special Operations Training in the State of Hawaii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

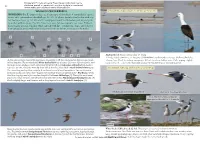

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

Updating the Seabird Fauna of Jakarta Bay, Indonesia

Tirtaningtyas & Yordan: Seabirds of Jakarta Bay, Indonesia, update 11 UPDATING THE SEABIRD FAUNA OF JAKARTA BAY, INDONESIA FRANSISCA N. TIRTANINGTYAS¹ & KHALEB YORDAN² ¹ Burung Laut Indonesia, Depok, East Java 16421, Indonesia ([email protected]) ² Jakarta Birder, Jl. Betung 1/161, Pondok Bambu, East Jakarta 13430, Indonesia Received 17 August 2016, accepted 20 October 2016 ABSTRACT TIRTANINGTYAS, F.N. & YORDAN, K. 2017. Updating the seabird fauna of Jakarta Bay, Indonesia. Marine Ornithology 45: 11–16. Jakarta Bay, with an area of about 490 km2, is located at the edge of the Sunda Straits between Java and Sumatra, positioned on the Java coast between the capes of Tanjung Pasir in the west and Tanjung Karawang in the east. Its marine avifauna has been little studied. The ecology of the area is under threat owing to 1) Jakarta’s Governor Regulation No. 121/2012 zoning the northern coastal area of Jakarta for development through the creation of new islands or reclamation; 2) the condition of Jakarta’s rivers, which are becoming more heavily polluted from increasing domestic and industrial waste flowing into the bay; and 3) other factors such as incidental take. Because of these factors, it is useful to update knowledge of the seabird fauna of Jakarta Bay, part of the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. In 2011–2014 we conducted surveys to quantify seabird occurrence in the area. We identified 18 seabird species, 13 of which were new records for Jakarta Bay; more detailed information is presented for Christmas Island Frigatebird Fregata andrewsi. To better protect Jakarta Bay and its wildlife, regular monitoring is strongly recommended, and such monitoring is best conducted in cooperation with the staff of local government, local people, local non-governmental organization personnel and birdwatchers. -

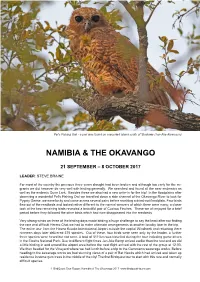

Namibia & the Okavango

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Plant Press, Vol. 18, No. 3

Special Symposium Issue continues on page 12 Department of Botany & the U.S. National Herbarium The Plant Press New Series - Vol. 18 - No. 3 July-September 2015 Botany Profile Seed-Free and Loving It: Symposium Celebrates Pteridology By Gary A. Krupnick ern and lycophyte biology was tee Chair, NMNH) presented the 13th José of this plant group. the focus of the 13th Smithsonian Cuatrecasas Medal in Tropical Botany Moran also spoke about the differ- FBotanical Symposium, held 1–4 to Paulo Günter Windisch (see related ences between pteridophytes and seed June 2015 at the National Museum of story on page 12). This prestigious award plants in aspects of biogeography (ferns Natural History (NMNH) and United is presented annually to a scholar who comprise a higher percentage of the States Botanic Garden (USBG) in has contributed total vascular Washington, DC. Also marking the 12th significantly to flora on islands Symposium of the International Orga- advancing the compared to nization of Plant Biosystematists, and field of tropical continents), titled, “Next Generation Pteridology: An botany. Windisch, hybridization International Conference on Lycophyte a retired profes- and polyploidy & Fern Research,” the meeting featured sor from the Universidade Federal do Rio (ferns have higher rates), and anatomy a plenary session on 1 June, plus three Grande do Sul, was commended for his (some ferns have tree-like growth using additional days of focused scientific talks, extensive contributions to the systematics, root mantle or have internal reinforce- workshops, a poster session, a reception, biogeography, and evolution of neotro- ment by sclerenchyma instead of lateral a dinner, and a field trip. -

Published Version

Int. J. Plant Sci. 174(3):350–363. 2013. Ó 2013 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 1058-5893/2013/17403-0009$15.00 DOI: 10.1086/668249 NEW OBSERVATIONS AND SYNTHESIS OF PALEOGENE HETEROSPOROUS WATER FERNS Margaret E. Collinson,1,* Selena Y. Smith,y Johanna H. A. van Konijnenburg-van Cittert,z,§ David J. Batten,k Johan van der Burgh,z Judith Barke,z and Federica Marone# *Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, United Kingdom; yDepartment of Earth and Environmental Sciences and Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, U.S.A.; zMarine Palynology Group, Laboratory of Palaeobotany and Palynology, Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands; §Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands; kSchool of Earth, Atmospheric, and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, United Kingdom, and Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Ceredigion SY23 3DB, United Kingdom; and #Swiss Light Source, Paul Scherrer Institute, CH-5232 Villigen, Switzerland Premise of research. Reproductive structures of modern genera of heterosporous water ferns (Marsileaceae and Salviniaceae) are widespread and abundant in plant mesofossil assemblages from the Paleogene. For Salviniaceae, whole fertile fossil plants give a good understanding of morphology. These fossils can be applied in paleoenvironmental analysis and to study water fern origin, evolution, and diversification. Methodology. New specimens were examined by SEM and TEM. Synchrotron x-ray tomographic microscopy (SRXTM) is evaluated as a nondestructive tool for investigating Azolla Lam. -

*Wagner Et Al. --Intro

NUMBER 60, 58 pages 15 September 1999 BISHOP MUSEUM OCCASIONAL PAPERS HAWAIIAN VASCULAR PLANTS AT RISK: 1999 WARREN L. WAGNER, MARIE M. BRUEGMANN, DERRAL M. HERBST, AND JOEL Q.C. LAU BISHOP MUSEUM PRESS HONOLULU Printed on recycled paper Cover illustration: Lobelia gloria-montis Rock, an endemic lobeliad from Maui. [From Wagner et al., 1990, Manual of flowering plants of Hawai‘i, pl. 57.] A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF THE RECORDS OF THE HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR 1998 Research publications of Bishop Museum are issued irregularly in the RESEARCH following active series: • Bishop Museum Occasional Papers. A series of short papers PUBLICATIONS OF describing original research in the natural and cultural sciences. Publications containing larger, monographic works are issued in BISHOP MUSEUM four areas: • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Anthropology • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Botany • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Entomology • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Zoology Numbering by volume of Occasional Papers ceased with volume 31. Each Occasional Paper now has its own individual number starting with Number 32. Each paper is separately paginated. The Museum also publishes Bishop Museum Technical Reports, a series containing information relative to scholarly research and collections activities. Issue is authorized by the Museum’s Scientific Publications Committee, but manuscripts do not necessarily receive peer review and are not intended as formal publications. Institutions and individuals may subscribe to any of the above or pur- chase separate publications from Bishop Museum Press, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817-0916, USA. Phone: (808) 848-4135; fax: (808) 841-8968; email: [email protected]. Institutional libraries interested in exchanging publications should write to: Library Exchange Program, Bishop Museum Library, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817-0916, USA; fax: (808) 848-4133; email: [email protected]. -

Insights from a Rare Hemiparasitic Plant, Swamp Lousewort (Pedicularis Lanceolata Michx.)

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 9-2010 Conservation While Under Invasion: Insights from a rare Hemiparasitic Plant, Swamp Lousewort (Pedicularis lanceolata Michx.) Sydne Record University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Record, Sydne, "Conservation While Under Invasion: Insights from a rare Hemiparasitic Plant, Swamp Lousewort (Pedicularis lanceolata Michx.)" (2010). Open Access Dissertations. 317. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/317 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSERVATION WHILE UNDER INVASION: INSIGHTS FROM A RARE HEMIPARASITIC PLANT, SWAMP LOUSEWORT (Pedicularis lanceolata Michx.) A Dissertation Presented by SYDNE RECORD Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2010 Plant Biology Graduate Program © Copyright by Sydne Record 2010 All Rights Reserved CONSERVATION WHILE UNDER INVASION: INSIGHTS FROM A RARE HEMIPARASITIC PLANT, SWAMP LOUSEWORT (Pedicularis lanceolata Michx.) A Dissertation Presented by -

Structure and Function of Spores in the Aquatic Heterosporous Fern Family Marsileaceae

Int. J. Plant Sci. 163(4):485–505. 2002. ᭧ 2002 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 1058-5893/2002/16304-0001$15.00 STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF SPORES IN THE AQUATIC HETEROSPOROUS FERN FAMILY MARSILEACEAE Harald Schneider1 and Kathleen M. Pryer2 Department of Botany, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60605-2496, U.S.A. Spores of the aquatic heterosporous fern family Marsileaceae differ markedly from spores of Salviniaceae, the only other family of heterosporous ferns and sister group to Marsileaceae, and from spores of all ho- mosporous ferns. The marsileaceous outer spore wall (perine) is modified above the aperture into a structure, the acrolamella, and the perine and acrolamella are further modified into a remarkable gelatinous layer that envelops the spore. Observations with light and scanning electron microscopy indicate that the three living marsileaceous fern genera (Marsilea, Pilularia, and Regnellidium) each have distinctive spores, particularly with regard to the perine and acrolamella. Several spore characters support a division of Marsilea into two groups. Spore character evolution is discussed in the context of developmental and possible functional aspects. The gelatinous perine layer acts as a flexible, floating organ that envelops the spores only for a short time and appears to be an adaptation of marsileaceous ferns to amphibious habitats. The gelatinous nature of the perine layer is likely the result of acidic polysaccharide components in the spore wall that have hydrogel (swelling and shrinking) properties. Megaspores floating at the water/air interface form a concave meniscus, at the center of which is the gelatinous acrolamella that encloses a “sperm lake.” This meniscus creates a vortex-like effect that serves as a trap for free-swimming sperm cells, propelling them into the sperm lake. -

Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service

Friday, April 5, 2002 Part II Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Revised Determinations of Prudency and Proposed Designations of Critical Habitat for Plant Species From the Island of Molokai, Hawaii; Proposed Rule VerDate Mar<13>2002 12:44 Apr 04, 2002 Jkt 197001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\05APP2.SGM pfrm03 PsN: 05APP2 16492 Federal Register / Vol. 67, No. 66 / Friday, April 5, 2002 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR the threats from vandalism or collection materials concerning this proposal by of this species on Molokai. any one of several methods: Fish and Wildlife Service We propose critical habitat You may submit written comments designations for 46 species within 10 and information to the Field Supervisor, 50 CFR Part 17 critical habitat units totaling U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific RIN 1018–AH08 approximately 17,614 hectares (ha) Islands Office, 300 Ala Moana Blvd., (43,532 acres (ac)) on the island of Room 3–122, P.O. Box 50088, Honolulu, Endangered and Threatened Wildlife Molokai. HI 96850–0001. and Plants; Revised Determinations of If this proposal is made final, section Prudency and Proposed Designations 7 of the Act requires Federal agencies to You may hand-deliver written of Critical Habitat for Plant Species ensure that actions they carry out, fund, comments to our Pacific Islands Office From the Island of Molokai, Hawaii or authorize do not destroy or adversely at the address given above. modify critical habitat to the extent that You may view comments and AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, the action appreciably diminishes the materials received, as well as supporting Interior. -

2010 Literature Citations

Annual Review of Pteridological Research - 2010 Literature Citations All Citations 1. Abbasi, T. & S. A. Abbasi. 2010. Enhancement in the efficiency of existing oxidation ponds by using aquatic weeds at little or no extra cost to the macrophyte-upgraded oxidation pond (MUOP). Bioremediation Journal 14: 67-80. [India; Salvinia molesta] 2. Abbasi, T. & S. A. Abbasi. 2010. Factors which facilitate waste water treatment by aquatic weeds - the mechanism of the weeds' purifying action. International Journal of Environmental Studies 67: 349-371. [Salvinia] 3. Abeli, T. & M. Mucciarelli. 2010. Notes on the natural history and reproductive biology of Isoetes malinverniana. Amerian Fern Journal 100: 235-237. 4. Abraham, G. & D. W. Dhar. 2010. Induction of salt tolerance in Azolla microphylla Kaulf through modulation of antioxidant enzymes and ion transport. Protoplasma 245: 105-111. 5. Adam, E., O. Mutanga & D. Rugege. 2010. Multispectral and hyperspectral remote sensing for identification and mapping of wetland vegetation: a review. Wetlands Ecology and Management 18: 281-296. [Asplenium nidus] 6. Adams, C. Z. 2010. Changes in aquatic plant community structure and species distribution at Caddo Lake. Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas USA. [Thesis; Salvinia molesta] 7. Adie, G. U. & O. Osibanjo. 2010. Accumulation of lead and cadmium by four tropical forage weeds found in the premises of an automobile battery manufacturing company in Nigeria. Toxicological and Environmental Chemistry 92: 39-49. [Nephrolepis biserrata] 8. Afshan, N. S., S. H. Iqbal, A. N. Khalid & A. R. Niazi. 2010. A new anamorphic rust fungus with a new record of Uredinales from Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. Mycotaxon 112: 451-456.