8001746.Pdf (6.41

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“PEACE, WHATEVER COMES.” a New Year’S Aspiration

I * * j t j f ¡ 4 » X? JÜMÙVütM-JlhBH Photo &y] CANAL SCENE IN THE PROVINCE OF CHEKIANG. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------r r r a ------------- “PEACE, WHATEVER COMES.” A New Year’s Aspiration. A CHINESE CHRISTIAN GENERAL Morgan & Scott, Ltd., 12, Paternoster Buildings, London, E.C.4 , or from any Bookseller; OR POST FREE 2S . 6 d . PER ANNUM FROM THE CHINA INLAND MISSION, NEWINGTON G r EEN, LONDON, N .l6. CHINA INLAND MISSION. Telegrams—Lammkkmuik, Hiiiuhy-Loniion. NEWINGTON GREEN, LONDON, N.16. Telephone 1K)7, Dal>t< I'lHihtlrr Tin- L a t e J. H r »SOX Tayi.OR, M.R.C.S. General Director : D. 33. HosTE. LONDON COUNCIL. Home Director .. .. .. .. .. .. R e v . J. S t u a r t Hoi.DE>*, M.A./-D.D. W ilL lA M S h a r p , Moorlands, Reigale. I Lt.-Col. J . W in n , R.E., Whyteleafe, The Grange, Wimbledon. C. T. PlSHE, 27, St. Andrews, Uxbridge, Mdx. I COT.. S. D. Cr.EEVE,C.B.,R.E., i5,Lansdo\vne Rd., Wimbledon.S.W. P. S. B a d e n o c h , Mildmay, Belmont. Road, Reigate. I H . M im > e r M o r r is . Mapledean, Linkfield Lane, Redhill, Surrey. W a i.TER B. S l o a n , F.R.G.S., (ilenconner, Bromley, Kent. ! E d w i n A. N e a t b y , M.D., 82, W7impole Street, W .i. Arch. O r r -I v w in g , Oak Bank, South Road, Weston-super-Mare. *1 W il l ia m W il s o n , M B., C.M., F.R.A.S., 43, FellowsRd., X.W .3. -

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE of DENIS KITCHEN Spring 2014 • the New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 Table of Contents

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE OF DENIS KITCHEN 0 2 1 82658 97073 4 in theUSA $ 8.95 ADULTS ONLY! A TwoMorrows Publication TwoMorrows Cover art byDenisKitchen No. 5,Spring2014 ™ Spring 2014 • The New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS HIPPIE W©©DY Ye Ed’s Rant: Talking up Kitchen, Wild Bill, Cruse, and upcoming CBC changes ............ 2 CBC mascot by J.D. KING ©2014 J.D. King. COMICS CHATTER About Our Bob Fingerman: The cartoonist is slaving for his monthly Minimum Wage .................. 3 Cover Incoming: Neal Adams and CBC’s editor take a sound thrashing from readers ............. 8 Art by DENIS KITCHEN The Good Stuff: Jorge Khoury on artist Frank Espinosa’s latest triumph ..................... 12 Color by BR YANT PAUL Hembeck’s Dateline: Our Man Fred recalls his Kitchen Sink contributions ................ 14 JOHNSON Coming Soon in CBC: Howard Cruse, Vanguard Cartoonist Announcement that Ye Ed’s comprehensive talk with the 2014 MOCCA guest of honor and award-winning author of Stuck Rubber Baby will be coming this fall...... 15 REMEMBERING WILD BILL EVERETT The Last Splash: Blake Bell traces the final, glorious years of Bill Everett and the man’s exquisite final run on Sub-Mariner in a poignant, sober crescendo of life ..... 16 Fish Stories: Separating the facts from myth regarding William Blake Everett ........... 23 Cowan Considered: Part two of Michael Aushenker’s interview with Denys Cowan on the man’s years in cartoon animation and a triumphant return to comics ............ 24 Art ©2014 Denis Kitchen. Dr. Wertham’s Sloppy Seduction: Prof. Carol L. Tilley discusses her findings of DENIS KITCHEN included three shoddy research and falsified evidence inSeduction of the Innocent, the notorious in-jokes on our cover that his observant close friends might book that almost took down the entire comic book industry .................................... -

International Bear News

International Bear News Quarterly Newsletter of the International Association for Bear Research and Management (IBA) and the IUCN/SSC Bear Specialist Group Summer 2013 Vol. 22 no. 2 ©I. Seryodkin Wilderness bear – Bears in wilderness make for inspiring photos, and may be used to promote the protection of wild areas. However, bears can also thrive in many human-dominated habitats as long as human-related mortality is low. Read the article written by the BSG Co-chairs on page 32. IBA website: www.bearbiology.org Table of Contents IBN Conservation Outreach News 3 International Bear News, ISSN #1064-1564 28 Spectacled Bear Museum Exhibit in Ecuador IBA Council News 4 From the President Student Forum 28 Truman’s List Serve IBA Grants Program News 5 New Development Director for the Bear IBA Member News Conservation Fund 29 Pioneering Grizzly Bear Researcher, Kate 6 A Letter of Introduction from Dr. Julia Kendall, Retires After 35 Years Bevins 7 Research & Conservation Grants Bears in Culture 9 Bear Conservation Fund Tops $73,000 in 30 Bears in Scotland 2013 10 Experience and Exchange Grants Bear Specialist Group 11 Applications for Experience & Exchange 32 Do Bears Need Wilderness? Are They a Grants Due in November “Symbol of the Wilderness”? 33 Distribution and food resources of Asiatic IBA Officers & Council black bears (Ursus thibetanus) and human- 11 IBA Elections 2013 bear conflict in the Panchase Protected 12 Nominees for President Forest of Nepal 13 Nominees for Vice-President Americas 35 Conditions of Captive Brown Bears in 14 Nominee -

Datcher Leaving RWU for DC

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU The eM ssenger Student Publications 9-29-1992 The esM senger -- September 29, 1992 Roger Williams University Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/the_messenger Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Roger Williams University, "The eM ssenger -- September 29, 1992" (1992). The Messenger. Paper 105. http://docs.rwu.edu/the_messenger/105 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Messenger by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spiritual Center celebration Page two VOLUME XV ISSUE II BRI.STOl, RI SEPTEMBER 29, 1992 problems Facing Students RWU struggles to Datcher leaving solve parking dilema RWU for DC interviewed in that pe lished in September of cars in the evening. whocan'tftnda space By ChriS Zammarelll By Wayne Shulman riod. Datcher said he 1991. rrheHawk'sNest We've been turning oncampuswtll prefer Managing Editor Sports Editor was interviewed in late isthe concessionstand awaypeoplewithyellow parking on Old Feny August. onthe lowerlevel ofthe For years, stu stickersornostickers." Road than North Dwight Datcher According to recreationcenter.) The dents at RWU have He added that Campus. 'The dis has resigned as head Datcher, everything athletic teams are also been complaining guests can use tance from Old Feny athletic director. was finally worked out going on more trips about the -parking security's phone to call Road ismuch shorter Datcher. who has been lastThursdayrughtand than they have in the problem.- However, uptheirfriendstocome than from North with the RWU athleUc he was able to an past. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Use a Machine Against Mail

fl^RNRW y9F«tit:^^i^v2wy‘<SK X NBT PRESS BUia A^'ERAGE DAILY CIRCULATION! THE WEATHER. OF THE EVENING HiCRAT.n for the month of September, 1990. Fair tonight, Friday clondy. Not 4,849 much change In temperature. VOL. XLV., NO. 12. Classified AdTeitislng on Page 0 MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, OCTOBER 14, 1926. PRICE THREE CENTS San Antone to 2 DEAD WOMEN DDUGIBLE LOS Boy Who Thinks He *s ^^Missing** Get the Legion Finds Out That He Really Was USE A MACHINE FOUND IN COVE for Year 1928 BRAVESINLAND Milwaukee, Oct. 14.— ‘T think‘s "Then numbers went throuigh I m missing— How can I tell you my head, 14-3-7, and then a word, AT l e HAVEN Philadelphia, Oct. 14.— San An F U G H H PERIL my name if I can’t remember it? ” ’shift.’ It came to me all of a sud tonio, Tex., will entertain the It was a plaintive, perplexed! American Legion In 1928. The den that I had been playing foot voice that came to Joseph Lebdw ball. 'Where do you suppose it w.as? AGAINST boys decided to meet two years over the telephone at Central Po- • MAIL Your, missing department must Bodies Discovered Under a hence in the Texas city after con Starts Late This Forenoon on “ I’m at a drug store some- i know.” sidering bids from San Antonio, where,,” Lebow was told next. j Miami, Detroit and Denver. “ Get into a taxicab and tell the • And the missing department did Boat Police Find Man Dan Moody, governor-elect of Trip That Proved Fatal driver to take you to headquar- i know. -

Jdh Mr Manso 258/4 (+)MR

APRIL 10 -14 THURSDAY, APRIL 10 Arrival & Check-In ........................................................... 7 AM to 1 PM Mandatory Breeder/Exhibitor Orientation Meeting & Dinner ....... 7 PM FRIDAY, APRIL 11 This sale Santa Gertrudis Show .................................................................. 9 AM will be International Brangus /Red Brangus Show ............................... 10 AM Florida Junior Brahman Association Show.................................. 11 AM broadcast International Cocktail Reception ..............................6 PM Magic City Brahman Genetics Heifer Sale ...................8 PM live at: CATTLEINMOTION.COM SATURDAY, APRIL 12 To view and bid on this sale live, simply log on to Cattleinmotion.com Commercial Heifer Beef Cattle Show ............................................ 9 AM and click on the sale that will be listed on the right hand side of the ABBA-Sanctioned Split Color Brahman Show ............ 10 AM screen. If you have never been to the CIM site, you must first create an account (24 hours in advance) to view and bid on a sale. Then pay your MONDAY, APRIL 14 $1 lifetime verification if you wish to bid. Show Cattle Release .................................................................... 7 AM Welcome!Dear Friends, Welcome to Miami-Dade County, and the Miami International Agriculture, Horse and Cattle Show. The show started seven years ago with the goal of bringing high tech initiatives to the Miami Dade County agriculture and agribusiness economy, and create jobs and revenue for Florida. Since Miami-Dade County is the strongest county, economically speaking, in Florida, and the “Capital of Latin America” we figured that our success with this show could fire-up, in the long run, the agricultural industry of our whole state, and this is happening. I am happy to report that, now going into our seventh year, we are moving forward, fast. -

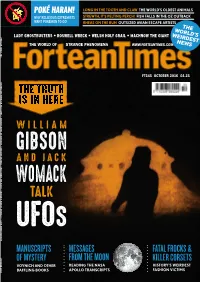

Womack and Gibson the Truth Is in Here

POKÉ HARAM! LONG IN THE TOOTH AND CLAW THE WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS WHY RELIGIOUS EXTREMISTS STREWTH, IT'S PELTING PERCH! FISH FALLS IN THE OZ OUTBACK WANT POKÉMON TO GO! RHEAS ON THE RUN OUTSIZED AVIAN ESCAPE ARTISTS THE WOR THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA LD’S LADY GHOSTBUSTERS • ROSWELL WRECK • WELSH HOLY GRAIL • MACHNOWWWW.FORTEANTIMES.COM THE GIANT WEIRDES FORTEAN TIMES 345 NEWS T THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA WWW.FORTEANTIMES.COM FT345 OCTOBER 2016 £4.25 GIBSON AND WOMACK TALK UFOS • MANUSCRIPTS OF MYSTERY • THE TRUTH IS IN HERE WILLIAM FA GIBSON SHION VICTIMS • MACHNOW THE GIANT • WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS • LADY GHOSTBUSTERS AND JACK WOMACK TALK UFOS MANUSCRIPTS MESSAGES FATALFROCKS& OCTOBER 2016 OFMYSTERY FROMTHEMOON KILLERCORSETS VOYNICH AND OTHER READING THE NASA HISTORY'S WEIRDEST BAFFLING BOOKS APOLLO TRANSCRIPTS FASHION VICTIMS LISTEN IT JUST MIGHT CHANGE YOUR LIFE LIVE | CATCH UP | ON DEMAND Fortean Times 345 strange days Pokémon versus religion, world’s oldest creatures, fate of Flight MH370, rheas on the run, Bedfordshire big cat, female ghostbusters, Australian fi sh fall, Apollo transcripts, avian CONTENTS drones, pornographer’s papyrus – and much more. 05 THE CONSPIRASPHERE 23 MYTHCONCEPTIONS 14 ARCHAEOLOGY 25 ALIEN ZOO the world of strange phenomena 15 CLASSICAL CORNER 28 NECROLOG 16 SCIENCE 29 FAIRIES & FORTEANA 18 GHOSTWATCH 30 THE UFO FILES features COVER STORY 32 FROM OUTER SPACE TO YOU JACK WOMACK has been assembling his collection of UFO-related books for half a century, gradually building up a visual and cultural history of the saucer age. Fellow writer and fortean WILLIAM GIBSON joined him to celebrate a shared obsession with pulp ufology, printed forteana and the search for an all too human truth.. -

Why Your Brain Always Looks on the Bright Side: the OPTIMISM BIAS by TALI S

Why your brain always looks on the bright side: THE OPTIMISM BIAS BY TALI S... Page 1 of 15 Cookie Policy Feedback Like 2.3m Follow @MailOnline DailyMail Friday, Dec 12th 2014 6PM 5°C 9PM 4°C 5-Day Forecast Home News U.S. Sport TV&Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel Fashion Finder Latest headlines You mag Event Books Promos Rewards Mail Shopping Bingo Horoscopes Property Motoring Columnists Stats Login Why your brain always looks on Site Web Enter your search the bright side THE OPTIMISM BIAS BY TALI SHAROT (Robinson £8.99) By JOHN HARDING FOR MAILONLINE UPDATED: 14:56, 6 January 2012 Jumping for joy: We are naturally optimistic Monty Python told us: ‘Always look on the bright side of life’, but it seems Ads by Google they needn’t have bothered because people do that anyway. 3 Months According to neuroscientist Tali Sharot the human brain is hardwired to Telegraph - £1 see the glass as half full rather than half empty. Like Follow www.telegraph.co. Daily Mail @MailOnline uk Sharot first stumbled on the phenomenon when researching people’s Tablet, mobile & web memories of the events of 9/11. She found that their later memories of the Follow +1 full access. Join day often diverged dramatically from what they reported at the time. today for as little as Daily Mail Daily Mail £1! Memories are constructed in an area of the brain called the hippocampus, Lumosity Fit Test and her research showed what every entertaining dinner guest already DON'T MISS www.lumosity.com knows: that we tend to embellish and enhance our recall of the past. -

Cows' Status for Haplotypes Impacting Fertility on the Records of 1 Holstein Association USA, Inc

Cows' status for haplotypes impacting fertility on the records of 1 Holstein Association USA, Inc. as of 04/11/2016 (Blank=Tested-Free, C=Carrier) Use CTRL-F to search Name Registration HH1 HH2 HH3 HH4 HH5 HCD M&C-FREDERICK CARLA-RED-ET USA 138158686 M&C-FREDERICK GOLD PRESENT USA 140013999 M&C-FREDERICK SHOT CARLY USA 140013971 C M&C-FREDERICK SHOTLE EVE-ET USA 140044115 C M&M-POND-HILL JALAPENO DODI USA 127817846 M-GEE O SILK-IMP-ET AUS H01594682 M-JAYBEE 39782 8063 582 USA 72083875 M-JAYBEE 39782 8416 716 USA 72084009 C M-JAYBEE 39782 8446 724 USA 72084017 C M-JAYBEE 39782 8498 844 USA 72084137 M-JAYBEE 39782 8540 808 USA 72084101 M-JAYBEE 39782 8553 829 USA 72084122 M-JAYBEE 39782 8648 835 USA 72084128 C C M-JAYBEE ACHOO 0 11186 USA 74173177 M-JAYBEE ACHOO 301 11194 USA 74173185 M-JAYBEE ACHOO 3331 11268 USA 74173259 M-JAYBEE ALFALFA 6294 11646 USA 74173637 M-JAYBEE ALFALFA 7500 11615 USA 74173606 M-JAYBEE ALOE 7479 7442 USA 66846320 M-JAYBEE ALSACE 103 11922 USA 74173913 M-JAYBEE ALSACE 112 11791 USA 74173782 M-JAYBEE ALSACE 37 11907 USA 74173898 M-JAYBEE ALSACE 428 12072 USA 74174063 M-JAYBEE ALSACE 66 11928 USA 74173919 M-JAYBEE ALTON 2292 5352 USA 63771839 M-JAYBEE ANTARES 2540 7414 USA 66846292 C M-JAYBEE ANTIOCH 812 8975 USA 70058907 1 M-JAYBEE ARDENT 6616 9961 USA 70059893 M-JAYBEE ARDENT 6650 9964 USA 70059896 M-JAYBEE ARDENT 8478 754 USA 72084047 M-JAYBEE ARDENT 8583 762 USA 72084055 M-JAYBEE ARDENT 8585 758 USA 72084051 M-JAYBEE ARDENT 8586 773 USA 72084066 M-JAYBEE ARDENT 8630 746 USA 72084039 M-JAYBEE ARDENT 8656 751 USA 72084044 M-JAYBEE ARDENT 8690 764 USA 72084057 M-JAYBEE ARDI 5915 11241-TW USA 74173232 C M-JAYBEE ARDIE 8342 11214 USA 74173205 C M-JAYBEE ARMITAGE 4924 460 USA 72083753 M-JAYBEE B BANG 5242 541-TW USA 72083834 C M-JAYBEE B BANG 5242 542-TW USA 72083835 M-JAYBEE BADGE 6466 258 USA 72083551 M-JAYBEE BALISTO 3680 11633 USA 74173624 M-JAYBEE BALISTO 7394 11611 USA 74173602 M-JAYBEE BCKEY 4238 9304-TW USA 70059236 Cows' status for haplotypes impacting fertility on the records of 2 Holstein Association USA, Inc. -

October 08,1896

The Republican Journal. ~~ 1896. _ THURSDAY, OCTOBER 8, _ BELFAST, MAINE, NUMBER 41. an 'Journal. Maine Good Templars. Obituary. The Churches. The New Shoe Factory. PERSONAL. 'rile 39th PERSONAL. US DAY MORNING BY THE semi-annual session of Marne Grand Esther The new shoe Lodge of Good was Hiclrborn who died in At the Unitarian church next fore- factory enterprise continues Fred J. Biather Templars held iu Ellingwood, Sunday of Boston was in town Mr. and Mrs. H. L. Woodcock went to Caribou, Oet. 1 and 2. Stockton was the Rev. J. M. will to advance in a business-like way and we last i Journal Pub. Co. The attendance was Springs, Sept. 27th, young- noon the pastor, Leighton, Saturday. Boston Tuesday for a short visit. est soon hear the hum and much smaller than daughter of Simon and Isabel on “The of the Sea.” shall rattle of the usual, owing to the Fletcher, speak Symbolism Oscar A. of was long Edgerley Elkhart, Ind., Mrs. Elizabeth Berry of Bostou is a distance from central and sister of Mrs. Ruth Ellis machinery in the old Dana building. The guest ,i*. on in and points; and a rain Clifford, who Rev. R. G. Harbutt of Searsport occupied in Belfast Sunday. of Mr. City County. survives and Mrs. Win. T. Howard. storm of three days duration her and sister of the late Oliver and the pulpit of the Congregational church Sun- Belfast Industrial Real Estate Company, prevented the Mrs. E. D. Ryder arrived home from ■ Crawford S. an able and dis- the which owns the E. -

Self-Presentation and Self-Positioning in Text-Messages: Embedded Multimodality, Deixis, and Reference Frame

Self-presentation and self-positioning in text-messages: Embedded multimodality, deixis, and reference frame Agnieszka Lyons Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2014 School of Languages, Linguistics & Film Queen Mary University of London Contents Acknowledgements 8 Abstract 10 1 Introduction 12 1.1 Texting: Definition and features . 16 1.2 Background and motivation . 18 1.3 Objectives of the thesis . 22 1.3.1 Methodological objectives . 23 1.3.2 Empirical objectives . 23 1.3.3 Theoretical objectives . 24 1.4 Outline of the thesis . 25 2 Data and methodology 28 2.1 Data and data-collection methods . 28 2.1.1 Obtaining consent . 30 2.1.2 Text-message choice . 31 2.1.3 Transcription error . 33 1 2.1.4 Participants and data collection . 33 2.2 Methodology . 39 2.2.1 Coding . 39 2.2.2 Anonymisation . 40 3 Theoretical framework 48 3.1 Understanding of communication . 49 3.1.1 Models of communication . 54 3.2 Meaning in communication . 68 3.2.1 Text and meaning-making . 69 3.2.2 Participants’ role in co-creating meaning . 72 3.2.3 Creating intended meaning: Pragmatics . 76 3.2.4 The role of context in EMC . 79 3.3 The role of the medium . 86 3.3.1 Mediated discourse analysis . 87 3.4 Multimodality . 88 3.4.1 Mode, modality, and medium . 89 3.4.2 Multimodality in various modes . 97 3.5 Summary . 99 4 Space, place and self-positioning 102 4.1 Places and spaces in mediated environments .