By Stefano Manganaro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Monastic Rules of Visigothic Iberia: a Study of Their Text and Language

THE MONASTIC RULES OF VISIGOTHIC IBERIA: A STUDY OF THEIR TEXT AND LANGUAGE By NEIL ALLIES A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham July 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis is concerned with the monastic rules that were written in seventh century Iberia and the relationship that existed between them and their intended, contemporary, audience. It aims to investigate this relationship from three distinct, yet related, perspectives: physical, literary and philological. After establishing the historical and historiographical background of the texts, the thesis investigates firstly the presence of a monastic rule as a physical text and its role in a monastery and its relationship with issues of early medieval literacy. It then turns to look at the use of literary techniques and structures in the texts and their relationship with literary culture more generally at the time. Finally, the thesis turns to issues of the language that the monastic rules were written in and the relationship between the spoken and written registers not only of their authors, but also of their audiences. -

Sellers Rieti

RIETI Panorama Loc.tà Casali Tancia, 6 02040 Monte S. Giovanni in Sabina (RI) tel. 0765.333330 fax 0765.333019 Casale Tancia [email protected] www.casaletancia.com L'azienda, situata ad una The agriturism, at 750 altezza di circa 750 metri, è m.s.l., is situated in a valley collocata all'interno di una full of exceptional natural vallata ricca di straordinarie beauties. It is also favoured bellezze naturali, favorita by a good climate for walks anche da un clima ideale and excursions all year per passeggiate e gite in round. The complex has ogni periodo dell'anno. Il been totally restructured complesso è stato comple- and combines perfectly with tamente ristrutturato inte- the natural environment. grandosi perfettamente con The management is a fa- l'ambiente naturale. La con- mily run concern and all the duzione dell'attività è di tipo products are strictly home familiare ed i prodotti sono grown. rigorosamente di produzio- Love and care for each ne propria. L'amore e la cu- small detail make this place ra per ogni piccolo partico- both magically pleasant and lare rende questo posto friendly. magico e accogliente al RIETI tempo stesso. Camere/Bungalow/Appartamenti Accomodation Piazzole camper/roulotte Areas for camper and roulotte Ristorante & bar Distanza da/Distance from Restaurant & bar • Aereoporto/Airport km. Servizi • Treno/Railway km. Services • Autostrada/Motorway km. Sala meeting & congressi Conference & reception rooms Periodo di apertura / Opening time Attività di intrattenimento Enterteinment themes Sala degustazione Linee di Prodotto Tasting room Prodotti tipici Mare del Lazio Typical Products Città d’Arte Network Direttore Ambiente General manager Enogastronomia Congressuale AGRITURISMO/FARM HOLIDAY Vocabolo Palombara snc SP 48 Km 15.500 La Tacita 02040 Roccantica (RI) tel. -

Le Ricerche Archeo Isbn

Le ricerche archeologiche nel territorio sabino: attività, risultati e prospettive Atti della giornata di studi Rieti, 11 maggio 2013 A cura di Monica De Simone - Gianfranco Formichetti IMpAGInAzIone e STAMpA Tipografia panfilo Mario - Rieti giugno 2014 IMMAGInI DI CopeRTInA: Museo Civico di Rieti - Venatio Museo Civico di Rieti - Urnetta cineraria MonICA De SIMone - GIAnFRAnCo FoRMICheTTI Le RICeRChe ARCheoLoGIChe neL TeRRIToRIo SAbIno: ATTIvITà, RISuLTATI e pRoSpeTTIve Atti della giornata di studi Rieti, 11 maggio 2013 RoTARy CLub RIeTI - DISTReTTo 2080 CoMune DI RIeTI - ASSeSSoRATo AL TuRISMo, CuLTuRe e pRoMozIone DeL TeRRIToRIo MuSeo CIvICo DI RIeTI 6 pReSenTAzIone Il Rotary Club di Rieti, sin dall’anno della sua fondazione avvenuta nell’or- mai lontano 1952, ha espresso in innumerevoli occasioni la sua costante attenzione al territorio, alle risorse umane ed ambientali, alla storia, alla tradizione ed alla cultura della città di Rieti e della sua provincia. Le tavole rotonde, gli incontri di studio e gli eventi culturali di cui il Rotary di Rieti si è reso promotore negli anni contribuiscono a realizzare, in concreto, l’obiettivo fondante di ogni Rotary Club del Mondo, vale a dire quello di promuo- vere e sviluppare relazioni amichevoli tra i propri soci per meglio renderli atti a “servire” l'interesse generale, informando ai principi della più alta rettitudine la pratica degli affari e delle professioni, riconoscendo la dignità di ogni occupazione utile a far sì che venga esercitata nella maniera più degna quale mezzo per “servire” la società ed orientando l'attività privata, professionale e pubblica dei singoli al concetto del “servizio”. Con la pubblicazione di questo importante volume, a conclusione della gior- nata di studio durante la quale sono state assemblate e confrontate le risultanze della lunga e strutturata attività archeologica del nostro territorio, ritengo che il Rotary Club di Rieti ed i suoi soci abbiano reso il loro doveroso “servizio” alla società reatina. -

358 363 Index Index

Index index Abū’l-‘Abbās, Charlemagne’s elephant: 26 Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Museum für Islamische Kunst, ivory Salvini, Anton Maria, scholar: 54 Theophilus, monk: 62 “Ada” ivories: 97 casket, inv. no. K3101: 102 Sanquirico, Antonio, art dealer: 92 Thomas, apostle, saint: 15, 126, 128, 129, 136, 157, 158, 162, Aethelwold of Winchester, Saint: 176 Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Museum für Islamische Kunst, Sanseverino, Lucio, Archbishop of Salerno: 211 221, 232, 233, 234, 237, 316, 317 Alagno, Cesario d’, Archbishop of Salerno: 207 oliphant, inv. no. K3106: 101 Sant’Agata de’ Goti, church of San Menna: 198 Todeschini Piccolomini, Antonio, Duke of Amalfi: 56 Alcuin, poet, educator, and cleric: 232 Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Kunstgewerbemuseum, enameled Sant’Angelo in Formis, abbey and church: 128, 171, 173, 175, Toesca, Pietro, art historian: 65, 66, 76, 77, 87, 94, 95, 214 Aldrovandi, Ulisse, naturalist: 83 cross: 226 177, 180, 224, 234 Toulouse, Basilica of St. Sernin: 100 Alessandro Ottaviano de’ Medici, cardinal: 91 Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Skulpturensammlung und Museum Saint-Denis, abbey: 222 Torcello: 105 Alexandria (Egypt): 45–47, 50, 57 für Byzantinische Kunst, Abraham (?) in front of an altar, Saint-Denis, treasury: 26 Trani (Apulia), cathedral: 187, 188 al-Mahdiya (Tunisia): 117 ivory plaque inv. no. 5952: 276 Schiavo, Armando, architectural historian: 206–208, 215, 217, Troia (Apulia), Exultet: 128 Alphanus I, Archbishop of Salerno: 182, 184, 186 191, 219, Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Skulpturensammlung und Museum 219, 220 Trombelli, Giovanni Grisostomo, cleric, librarian: 85 236, 237 für Byzantinische Kunst, Crucifixion, ivory plaque, inv. no. Schmid, Max, art historian: 86 Turin, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria, ms. -

Farfa Back Into the Early Middle Ages

Marios Costambeys. Power and Patronage in Early Medieval Italy: Local Society, Italian Politics and the Abbey of Farfa, c.700-900. Cambrdige Studies in Medieval Life and Thought Series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Tables, charts. xvi + 388 pp. $115.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-521-87037-5. Reviewed by Tehmina Goskar Published on H-Italy (January, 2011) Commissioned by Monica Calabritto (Hunter College, CUNY) The Abbey of Farfa, nestled in the Sabine work with them, particularly Don Alfonso, to re‐ hills, and little known on the tourist trail, has sur‐ plant the garden and regain some of its former vived to this day with its community of Benedic‐ glory--the visible glee on Alfonso’s face when it all tine monks because it has constantly diversified started to bloom again was testament to the still its activities and reasons for existing. Today, the continuing importance of religious and lay people abbey is online, allowing you to take a virtual tour working together to retain the profound sense of of its beautiful interiors--what was once the prod‐ place a major religious center can give a locality. uct of patronage and the intimate relationship be‐ And so to Farfa in the early Middle Ages, a tween lay and monastic realms is now a museum. time during which cycles of exchange and negoti‐ [1] You can book yourself in for a retreat and en‐ ation established the abbey as a European politi‐ joy “un’esperienza monastica.” “La nuova Farfa” cal powerhouse and a considerable influence on is now a social enterprise running socially mind‐ the changes experienced in the region. -

Reconciling the Narratives of Incastellamento in Archaeology and Text

ABSTRACT Toubert or Not Toubert: Reconciling the Narratives of Incastellamento in Archaeology and Text Ashley E. Dyer Director: Davide Zori, Ph.D. During the Middle Ages, castles spread across the Italian countryside in a process called incastellamento, during which the population moved from dispersed settlements to concentrated and fortified sites atop hills and plateaus. The French historian Pierre Toubert spearheaded intensive study of this phenomenon in 1973 with a landmark work outlining its mechanisms and chronology. However, archaeologists took issue with several of Toubert’s key findings, calling his research into question and exemplifying the inherent tension between textual and material sources. In this thesis, I analyze Toubert’s monumental work and examine archaeological critiques of it. I then formulate my own definition of incastellamento before exploring how it is observed in the archaeological data, using several examples of sites from archaeological excavations and applying the analysis to the ongoing excavation in San Giuliano, Italy. Ultimately, this study acts as an illustration of the importance of interdisciplinary studies in the analysis of archaeological sites moving forward. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: ________________________________________________ Dr. Davide Zori, Baylor Interdisciplinary Core APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ________________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Corey, Director DATE: ________________________ TOUBERT OR NOT TOUBERT: RECONCILING THE NARRATIVES OF INCASTELLAMENTO -

New Farfa Flyer 2020

Farfa, Italy www.eldershipacademy.org September 10–17th, 2020 JOY IN LIVING AND AGING September 10th –17th, 2020 What will happen? • Experiential and interactive learning, group work, expressive arts through clay, and optional b e g i n n i n g Yo g a a n d b o d y exercises. Uncover and shift attitudes about aging in a heartful and vibrant learning community. Enjoy the beauty of the natural surroundings and be nourished by the care and serenity of our hosts. You will have ample opportunity in this peaceful setting to allow yourself to go deep within, be mindful and reflective. Our Retreat in Farfa, Italy Eldership is a new attitude towards life and aging. Arnold What can you expect to Mindell’s Processwork is a theoretical and practical frame for take away? embracing hopes, fears and dreams as they revolve around aging and living life itself. • A new appreciation for the A Processwork mindset follows the joy principle: a sense that hidden richness in your daily life. life’s complications – even those that we don't want and didn't ask for - present opportunities to learn and grow. Rather than • New directions for enjoying and feeling burdened, being critical, feeling down about your contributing your innate talents in aging and complex life, you can begin to welcome and your projects and encounters. appreciate it, look forward to the process of maturation, have • A joyous attitude to life and aging. the ability to counter your own ageism: anxieties and criticisms that put you down for growing old and older. -

I Cimiteri Paleocristiani Del Lazio Ii Sabina

MONUMENTI DI ANTICHITÀ CRISTIANA PUBBLICATI A CURA DEL PONTIFICIO ISTITUTO DI ARCHEOLOGIA CRISTIANA II SERIE XX VINCENZO FIOCCHI NICOLAI I CIMITERI PALEOCRISTIANI DEL LAZIO II SABINA 2009 CITTÀ DEL VATICANO ISBN 978-88-85991-48-4 © Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 2009 I-00185 Roma, Via Napoleone III, 1 Tel. 064465574 - Fax 064469197 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.piac.it A Pasquale Testini ELENCO DELLE ABBREVIAZIONI AA. SS. = Acta Sanctorum, ed. PP. Bollandisti, Anversa, Bruxelles, Tongerloo, 1643 ss.; 3ª ed., Parisiis et Romae 1863-1887. ALVINO, Via Salaria = G. ALVINO, Via Salaria, Roma 2003. AMORE, Martiri = A. AMORE, I martiri di Roma, Roma 1975. ANDREOZZI, Diocesi = A. ANDREOZZI, Le antiche diocesi sabine, I, Cures-Nomentum, Roma 1973. Archeol. Laz. = Archeologia Laziale, I-XII. Incontri di studio del Comitato per l’archeologia laziale (= Quaderni del Centro di studi per l’archeologia etrusco-italica (poi Qua- derni di archeologia etrusco-italica), 1, 3-5, 7-8, 11, 14, 16, 18-21, 23, 24), Ro- ma 1978-1993. Arch. Centr. Stato = Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Roma. Arch. P. C. A. S. = Archivio della Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra. Arch. Stato Roma = Archivio di Stato di Roma, Roma. ARMELLINI, Cimiteri = M. ARMELLINI, Gli antichi cimiteri cristiani di Roma e d’Italia, Roma 1893. ASHBY, Classical Topography = TH. ASHBY, The Classical Topography of the Roman Campagna. Part II, in BSR, 3, 1906, pp. 1-212. ASHBY, Roman Campagna = TH. ASHBY, The Roman Campagna in Classical Times, London 1927, edizione italiana, Milano 1982. BAC = Bullettino di Archeologia Cristiana, Roma 1863-1894. BAILEY, Roman Lamps = D. -

Azienda Agricola Laura Petrocchi Via Vocabolo Alberici, Snc Mompeo (RI) Tel/Ph

Azienda Agricola Laura Petrocchi Via Vocabolo Alberici, snc Mompeo (RI) Tel/Ph. +39. 0765.469034; 3932091931 mail: [email protected] web: www.laurapetrocchi.it Our company Azienda Agricola Laura Petrocchi is located in Mompeo, an ancient village built around the ancient Fundus Pompeianus fortress and now acknowledged as one of Italy’s most beautiful hamlets. The family-run farm’s products reflect local traditions, thanks to decades of experienced handed down from father to sons. Thanks to the carefully selected and well-tended plants, and a patient and methodical organic approach to agriculture, our products, made with the Carboncella, Frantoio, and Leccino cultivars, are guaranteed to be genuine. Harvesting is by hand according to traditional custom, and the olives are pressed on the day of harvesting to obtain extravirgin olive oil. Our products “Azienda Agricola Laura Petrocchi” organic extravirgin olive oil, available in 0.10 l and 1 litre bottles with handles and 3 l and 5 litre jars. Our olive oil is available all year round and is sold and distributed at our sales outlet; it can also be purchased online. Directions From Rome: take the A1 motorway towards Florence, exit at Fiano Romano, and follow indications to Mompeo-Rieti. After passing the Farfa Abbey, follow the indications to Mompeo - Vocabolo Alberici. Activities Guided tastings at the farm and/or sales outlet (30 minutes; minimum of 5 people); Brief olive pruning course (3 hours, minimum of 5 people and maximum of 10, depending on available facilities and equipment); Helping with the olive harvest; Visit to the farm’s olive press to watch the various phases of olive processing (1 hour; minimum of 5 people and maximum of 10. -

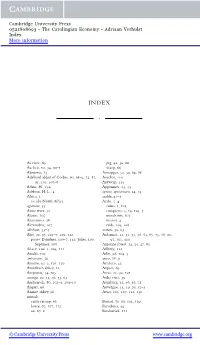

The Carolingian Economy - Adriaan Verhulst Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521808693 - The Carolingian Economy - Adriaan Verhulst Index More information INDEX . Aa river, 69 pig, 42, 50, 66 Aachen, 12, 34, 90–1 sheep, 66 Abruzzes, 13 Annappes, 32, 39, 64, 78 Adalhard abbot of Corbie, 60, 68–9, 75, 87, Anschar, 110 93, 101, 107–8 Antwerp, 134 Adam, H., 130 Appenines, 13, 35 Adelson, H. L., 4 aprisio, aprisionarii, 14, 53 Africa, 3 arable, 41–3 see also North Africa Arabs, 2–4 agrarium, 53 coins, 3, 105 Aisne river, 32 conquests, 3, 14, 103–5 Alcuin, 107 merchants, 105 Alemannia, 26 money, 4 Alexandria, 107 raids, 104, 108 allodium, 53–4 aratura, 50, 63 Alps, 92, 95, 104–7, 109, 112 Ardennes, 12, 34, 55, 58, 63, 65, 73, 76, 90, passes: Bundner,¨ 106–7, 112; Julier, 106; 97, 101, 110 Septimer, 106 Argonne forest, 34, 35, 47, 83 Alsace, 100–1, 109, 111 Arlberg, 112 Amalfi, 106 Arles, 98, 104–5 ambascatio, 50 arms, 78–9 Amiens, 92–3, 101, 130 Arnhem, 55 Amorbach abbey, 12 Arques, 69 Ampurias, 54, 105 Arras, 22, 90, 101 ancinga, 20, 43, 46, 55, 63 Aube river, 50 Andernach, 80, 102–3, 109–10 Augsburg, 42, 46, 56, 73 Angers, 98 Auvergne, 13, 19, 20, 52–3 Aniane abbey, 98 Avars, 105, 107, 112, 130 animals cattle raising, 66 Badorf, 79–80, 103, 109 horse, 67, 107, 112 Barcelona, 54 ox, 67–8 Bardowiek, 111 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521808693 - The Carolingian Economy - Adriaan Verhulst Index More information 152 Index Barisis, 82–3 carropera, 50 Bas-Languedoc, 19 carruca, 67 Bastogne, 90, 97 casata, 44 Bavaria, 32, 35, 42–3, 55–6, 82, 99, 105, castellum, -

Scarica La Guida [Pdf 4.8

Il progetto “Biblioteche digitali” finanziato dalla Regione Lazio rappresenta uno degli strumenti messi in atto dall’Unione di Comuni della Bassa Sabina per rispondere agli impegni presi sulla promozione del territorio. Risponde in primo luogo alle esigenze del territorio stesso: conoscere per programmare. Una programmazione a misura del territorio, consapevole e sostenibile, capace di promuovere le eccellenze, che mira allo sviluppo locale, che salvaguarda le risorse ambientali, mantiene l’identità culturale e soprattutto coinvolge positivamente le comunità locali. Sono convinto che se si vuole mettere in campo un programma di promozione responsabile e sostenibile occorre un’azione collettiva, che coinvolga i soggetti pubblici e privati presenti sul territorio mettendo insieme energie e capacità. In questa direzione stiamo proseguendo anche con altri progetti che mettono in rete tutti i servizi culturali, compresi archivi storici e musei. Infatti, la creazione della rete messa in campo dall’Unione di Comuni della Bassa Sabina ed il Sistema Bibliotecario insieme alle altre Unioni, ai soggetti privati ed alle associazioni locali ha come obiettivo fondamentale di aiutare il territorio stesso a conoscere le proprie caratteristiche e i propri punti di forza. C’è ancora molto da lavorare, e se vogliamo far brillare la nostra amata perla Sabina abbiamo bisogno di tutti voi, dei vostri talenti, delle vostre idee e suggerimenti. Assessore alla Cultura Ilario Di Loreto Spezzano SP54 Montebuono SP54 Rocchette Magliano Spezzano Sabina Collepietro -

Umbria Umbria, St Francis and the Dukes of Spoleto

Telephone: +44 (0) 1722 322 652 Email: [email protected] Umbria Umbria, St Francis and the Dukes of Spoleto https://www.onfootholidays.co.uk/routes/umbria/ Route Summary At a glance 8 nights (7 days walking) - the full route. We recommend extra nights in Spoleto, Labro, Casperia and Misciani, and a night in Rome. How much walking? Full days: 12-21 km per day, 4¾-6¾ hrs walking Using shortening options: 8-16 km per day, 2¾-5½ hrs (using lifts) Max. Grade: page 1/9 A remarkable extended walk down the spine of Italy from Spoleto, just south of Assisi, to the abbey of Farfa, at the southern tip of the Sabine Hills, designed for the experienced walker. It goes through the territory of the old Duchy of Spoleto, which was founded by the Lombards in the 6th century AD. Its destination, the abbey, was founded by Duke Faraold II of Spoleto in the 7th century. Much of the first few days uses the Via Francigena, so Saint Francis is never far away in the churches and shrines you pass. From the medieval town of Spoleto, with its cathedral, fortress, ancient streets and sophisticated streetlife, your walk leads you (after a short lift at the start) over the hills to the pretty Val Nerina at Ferentillo; onward past vine-clad pastures to the lake at Piediluco, the last remnant of a stretch of water that once filled the whole of the Rieti Plain. Stay at hilltop Labro in one of two beautifully restored village houses, before crossing the Plain to the Sabine Hills at Greccio, where Saint Francis is believed to have invented the Christmas Nativity scene, and whose cell you can visit.