Martina Margetts History in the Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CELSIUS a Peer-Reviewed Bi-Annual Online Journal Supporting the Disciplines of Ceramics, Glass, and Jewellery and Object Design

CELSIUS A peer-reviewed bi-annual online journal supporting the disciplines of ceramics, glass, and jewellery and object design. ISSUE 1 July 2009 Published in Australia in 2009 by Sydney College of the Arts The Visual Arts Faculty The University of Sydney Balmain Road Rozelle Locked Bag 15 Rozelle, NSW 2039 +61 2 9351 1104 [email protected] www.usyd.edu.au/sca Cricos Provider Code: 00026A © The University of Sydney 2009 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the copyright owners. Sydney College of the Arts gratefully acknowledges the contribution of the artists and their agents for permission to reproduce their images and papers. Editor: Jan Guy Publication Layout: Nerida Olson Disclaimers 1. The material in this publication may contain references to persons who are deceased. 2. The artwork and statements in this catalogue have not been classified for viewing purposes and do not represent the views or opinions of the University of Sydney or Sydney College of the Arts. www.usyd.edu.au/sca/research/projects/celsiusjournal CELSIUS A peer-reviewed bi-annual online journal supporting the disciplines of ceramics, glass, and jewellery and object design. Mission Statement The aims of Celsius are to - provide an arena for the publication of scholarly papers concerned with the disciplines of ceramics, glass and jewellery and object design - promote artistic and technical research within these disciplines of the highest standards -foster the research of postgraduate students from Australia and around the world - complement the work being done by professional journals in the exposure of the craft based disciplines -create opportunities of professional experience in the field of publication for USYD postgraduate students Editorial Board The Celsius Editorial Board advises the editor and helps develop and guide the online journal’s publication program. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Art Galleries Committee, 17/02/2021

Public Document Pack Art Galleries Committee Date: Wednesday, 17 February 2021 Time: 9.30 am Venue: Virtual meeting – https://vimeo.com/509986438 Everyone is welcome to attend this committee meeting. The Local Authorities and Police and Crime Panels (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority and Police and Crime Panel Meetings) (England and Wales) Regulations 2020. Under the provisions of these regulations the location where a meeting is held can include reference to more than one place including electronic, digital or virtual locations such as Internet locations, web addresses or conference call telephone numbers. To attend this meeting it can be watched live as a webcast. The recording of the webcast will also be available for viewing after the meeting has ended. Membership of the Art Galleries Committee Councillors - Akbar, Bridges, Craig, Leech, Leese, N Murphy, Ollerhead, Rahman, Richards and Stogia Art Galleries Committee Agenda 1. Urgent Business To consider any items which the Chair has agreed to have submitted as urgent. 2. Appeals To consider any appeals from the public against refusal to allow inspection of background documents and/or the inclusion of items in the confidential part of the agenda. 3. Interests To allow Members an opportunity to [a] declare any personal, prejudicial or disclosable pecuniary interests they might have in any items which appear on this agenda; and [b] record any items from which they are precluded from voting as a result of Council Tax/Council rent arrears; [c] the existence and nature of party whipping arrangements in respect of any item to be considered at this meeting. Members with a personal interest should declare that at the start of the item under consideration. -

Hans Coper and Pupils Press Release

Hans Coper, Lucie Rie & Pupils Hans Coper, Spade Form (1967) height 19 cms. Image: Michael Harvey Influential potter Hans Coper (1920-1981) was a champion of arts education. “His teaching had the same integrity and strength as had his pots; graceful, direct, precisely and sensitively tuned...” 1 In this his centenary year, Oxford Ceramics Gallery celebrate this element of Coper’s work with their forthcoming exhibition Hans Coper, Lucie Rie and Pupils (15th May - 4th July) A leader in the development of ceramics in the twentieth century Coper taught at Camberwell and then at Royal College of Art alongside his own teacher and mentor Lucie Rie (1902 - 1995). 1 Tony Birks. Hans Coper. (New York: Harper & Row, 1983), 61. Group of works by Lucie Rie on shelf including Bronze Vase (central) alongside a coffee pot and jug with white glaze and pulled handles. Newly sourced examples of Coper’s work are shown alongside fine examples from Lucie Rie and key works from the following generation of their pupils who went on to define the range and creative brilliance of British Studio Pottery. Exhibitors in- clude: Alison Britton, Elizabeth Fritsch, Ian Godfrey, Ewen Henderson, Jacqueline Poncelet & John Ward. Alison Britton, White Jar (1991) 34 x 46 x 19.5 cm. image: James Fordham. Born in Chemnitz, Germany, Hans Coper (1920-1981) came to England in 1939 as an engineering student and in 1946 he began working as an assistant to the Austrian potter Lucie Rie (1902-1995) in her studio in London, taking him on with no formal training in ceramics. -

Dodo Anda 2019.Pdf (2.296Mb)

Contemplations in the natural landscape: Unearthing the surface in the ceramic vessels of Anda Dodo. Anda Dodo 211547819 Supervisor: Mrs Michelle Rall 838290 Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art in Fine Art, Centre for Visual Art, University of KwaZulu-Natal; Pietermaritzburg (October 2019) i Contemplations in the natural landscape: Unearthing the surface in the ceramic vessels of Anda Dodo. Anda Dodo ii iii Acknowledgements and thanks Firstly, I would like to specifically acknowledge the invaluable financial support offered to me through the Rita Strong Scholarship and the GC Weightman-Smith Scholarship. I would like to convey my sincere thanks to the following people: • My supervisor, Michelle Rall, I am eternally grateful for your patience and guidance through this entire journey • Professor Ian Calder whose advice has never led me astray • I would like to thank staff and colleagues at the CVA for their support and guidance • Close friends and confidants; Natasha Hawley, Jessica Steytler, Georgina Calder, Anita Dlamini, Noxolo Ngidi, Ayanda Mthethwa-Siwila, Alicia Madondo, Siziphiwe Shoba, Dexter Sagar and Sinenhlanhla Memela your friendship means everything • My siblings and parents who continue to support me, I thank you for being a positive presence in my life iv This dissertation is dedicated to my late khulu Mrs Zandile Mvusi, may your presence forever guide me. v Abstract This Practice-Based Masters research project comprises this written dissertation together with the creative studio practice of Anda Dodo. The focus of this qualitative research is non- utilitarian nature-inspired ceramic vessels. The theoretical framework of PBR and heuristic inquiry, which positions Dodo at the centre of her research and foreground her insights as a research practitioner, are used together with interrelated theories. -

Fritsch E Biography

Elizabeth Fritsch CBE Curriculum Vitae Born 1940, Wales 1958-1964 Birmingham School of Music & Royal Academy of Music, London 1968-1971 Royal College of Art, London, MA Ceramics Working in London Museums and collectors across the world have been admirers of Elizabeth Fritsch's work for decades. Her hand-built fore-shortened forms combined with rhythmic patterns are signatures that are widely-recognised and inspired by her training as a classical musician before turning to ceramics. Works are often grouped together and juxtaposed so that the rear or side of a vase balances or provides a counterpoint to a neighbour. Having graduated from the Royal College of Art, London in 1971, Elizabeth is regarded as one of the UK's leading ceramic artists. Elizabeth Fritsch -2 - Selected Solo Exhibitions 2010 Dynamic Structures: Painted Vessels, National Museum Cardiff, Wales, in association with Adrian Sassoon 2008 The Fine Art Society, London 2007 Anthony Hepworth Fine Art, Bath 2000 Memory of Architecture, Part II, Galerie Besson, London Metaphysical Vessels, Mobilia Gallery, Cambridge, USA 1998 Sea Pieces, Contemporary Applied Arts, London 1995-1996 Metaphysical Pots, Museum Bellerive, Zurich, Switzerland & tour to Munich, Halle & Karlsruhe, Germany 1994 Order and Chaos, Bellas Artes, Santa Fe, USA Osiris Gallery, Brussels 1993-1995 Vessels from Another World, (retrospective) Northern Centre for Contemporary Art, Sunderland & tour to Aberdeen, Birmingham, Cardiff, London, Norwich 1992-1993 Pilscheur Fine Art, London, (retrospective) 1990-1991 Hetjens -

Hans Coper – (1920 – 1981)

HANS COPER – (1920 – 1981) Hans Coper was among the artists who fled Hitler’s Germany in the late 1930’s and settled in England. Employment in the ceramic button workshop of fellow refugee Lucie Rie resulted in both his introduction to ceramic art, which would become his life’s work, and a close friendship with Rie that would be mutually supportive and enriching. Coper and Rie worked together at her studio until 1958 when Coper set out on his own. By that time he was already a recognized potter, but in the years to come his style would mature and he would become one of the major figures of twentieth century ceramics. His stoneware vessels were wheel-thrown and then altered and assembled and finished with oxides, slips and textures. The pieces are sculptural, not functional, but are always vessels reflecting Coper’s commitment to what he called the essence of the clay. Hans Coper’s work and life were cut short by the onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in 1975 which diminished his ability to work and ultimately took his life in 1981. “Although Lucie Rie outlived Hans Coper by fourteen years, and the aims of modern potters were reshaped in this period, no one has come forward to take their place, especially the place of Hans. He combined originality with an uncompromising search for excellence, and his legacy of work is his memorial.”1 1. Tony Birks. Hans Coper. (New York: Harper & Row, 1983), 79. ARTIST’S STATEMENT – HANS COPER “My concern is with extracting essences rather than with experiment and exploration. -

Westminsterresearch Re-Modelling Clay: Ceramic Practice and the Museum in Britain

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Re-modelling clay: ceramic practice and the museum in Britain (1970-2014) Breen, L. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Miss Laura Breen, 2016. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] RE-MODELLING CLAY: CERAMIC PRACTICE AND THE MUSEUM IN BRITAIN (1970-2014) LAURA MARIE BREEN A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy This work forms part of the Behind the Scenes at the Museum: Ceramics in the Expanded Field research project and was supported by the AHRC [grant number AH/I000720/1] June 2016 Abstract This thesis analyses how the dialogue between ceramic practice and museum practice has contributed to the discourse on ceramics. Taking Mieke Bal’s theory of exposition as a starting point, it explores how ‘gestures of showing’ have been used to frame art-oriented ceramic practice. Examining the gaps between the statements these gestures have made about and through ceramics, and the objects they seek to expose, it challenges the idea that ceramics as a category of artistic practice has ‘expanded.’ Instead, it forwards the idea that ceramics is an integrative practice, through which practitioners produce works that can be read within a range of artistic (and non-artistic) frameworks. -

Herefore Greater Value (I.E., Theexhibitions Reflect This Event Everywhere

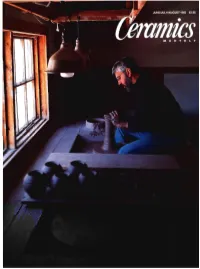

June/July/August 1995 1 Spencer L. DavisPublisher and Acting Editor Ruth C. Butler........................Associate Editor Kim Nagorski........................ Assistant Editor Tess Galvin...........................Editorial Assistant Randy Wax....................................Art Director Mary Rushley....................Circulation Manager Mary E. Beaver .... Assistant Circulation Manager Connie Belcher................Advertising Manager Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Post Office Box 12788 Columbus, Ohio 43212-0788 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly {ISSN 0009-0328) is published monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc., 1609 Northwest Boulevard, Columbus, Ohio 43212-0788. Second Class post age paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscrip tions outside the U.S.A. In Canada, add GST (registration number R123994618). Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Department, Post Office Box 12788, Columbus, Ohio 43212-0788. Contributors: Manuscripts, announcements, news releases, photographs, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustrations and digital TIFF or EPS images are welcome and will be considered for publication. Mail submis sions to Ceramics Monthly, PostOffice Box 12788, Columbus, Ohio 43212-0788. We also accept unillustrated materials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines:Printed information on standards and procedures for submitting materials is available upon request. Indexing:An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Additionally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) index ing is available through Wilsonline, 950 Univer sity Avenue, Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Company, 362 Lakeside Drive, Forest City, California 94404. -

18-20-GALLERY V3.Indd

For more, follow CERAMICS | SHOWS Ceramic Review on Twitter; twitter.com/ Gallery ceramicreview Our pick of the latest top shows to see Perspectives Drawn out For Sketching in Clay: 100 Bottles in 100 Days, a touring exhibition coming soon on porcelain to the Craft Centre and Design Gallery in Leeds, the Yorkshire ceramist Anna Over the last decade, an increasing number of artists have been turning to porcelain to explore their ideas. The Whitehouse set herself a rather unusual Precious Clay: Porcelain in Contemporary Art at the Museum of Royal Worcester juxtaposes examples of this trend brief: to make one bottle a day for 100 days. with the museum’s historic collection, which is housed on the site of what was once a porcelain factory. Highlights The aim was to ‘free up my making and include a pair of conjoined teacups by Mona Hatoum, a new commission by Laura White reflecting on value, rarity explore ideas quickly,’ explains Whitehouse. and mass production entitled White Mud, and an exploded then reassembled Worcester Teapot with Butterflies Using a two-part press mould, she created a plain piece each day, which would then act as a canvas for the (pictured) by former ceramics conservator Bouke de Vries. Until 20 March; museumofroyalworcester.org patterns and textures filling her sketchpads. The pots, which feature carved, impressed and handbuilt designs, were left unglazed – their whiteness intending to reflect that of the white drawing paper she used for her ideas. Folk futures Potting partnership 8 January–20 April; craftcentreleeds.co.uk Yova Raevska: The Voice Five years after the 50th anniversary of Clay aims to restore an exhibition of David and Margaret Frith’s Women’s EDITOR’S important ceramic artist Brookhouse Pottery, the pair return to Smells like pots CHOICE to wider cultural awareness. -

York Museums Trust Performance Report: April – September 2010

Annex 1 York Museums Trust Performance Report: April – September 2010 Executive Summary 1. The last 6 months our work has been dominated by the £2 million refurbishment of the Yorkshire Museum. The museum closed in November 2009 and reopened on 1 August, Yorkshire Day. The City of York Council funded the project with £800,000 which we matched with other funds largely from Trusts and Foundations, the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (MLA) and monies we raised ourselves with volunteer help. The CYC contribution was part of the dowry that CYC allocated to YMT in 2002 to help with levering in additional investments. 2. Our ambition with the refurbishment was to double visitor numbers to 150,000 per annum. The additional admission income would add to our sustainability but also we wanted to raise the awareness of the Yorkshire Museum with local residents. We knew that few local people visited the museum, retaining their interest largely with the Castle Museum. We worked on a marketing campaign with Your Local Link magazine that offered free Golden tickets exclusively for local residents the day before the grand opening. We had over 2,229 visitors and there were queues outside the museum all day. Another 7,664 York Card holders visited in August, so just short of 10,000 York residents came to see the museum in the first 32 days. 3. We have also been building up income streams in anticipation of public sector cuts. We know that MLA will be abolished by 2012. There will be a transitional year in 2011-12 but it is quite unlikely that any regular revenue funding will be available to YMT from this source from 1 April 2012. -

Manchester Art Gallery Collection Development Policy 2021-2024

Manchester Art Gallery Collection Development Policy 2021-2024 Name of museum: Manchester Art Gallery Mosley Street, Manchester M2 3JL Platt Hall, Rusholme, Manchester, M14 5LL Name of governing body: Manchester City Council (Art Galleries Committee) Approved by governing body: Art Galleries Committee meeting 17 February 2021. Policy Review Procedure: Our Collection Development Policy is reviewed, revised and published every three years. Arts Council England will be notified of any changes to the Collection Development Policy, and the implications of any such changes for the future of Manchester Art Gallery’s collections. Date of next review: 1st September 2022 Manchester Art Gallery Collection Development Policy 2021-24 Page 2 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Objective ................................................................................................................... 5 Our Vision and Who We Are ....................................................................................................... 5 Statement of Purpose ................................................................................................................. 6 Key Principles ............................................................................................................................. 7 2 History of the Collection ........................................................................................................ -

Art & Design Collections

Art & Design Collections 1 Introduction Glasgow Museums’ art collection is one of the finest in the UK. It consists of some 60,000 objects covering a wide range of media including paintings, drawings, prints, sculpture, metalwork, ceramics, glass, jewellery, furniture and textiles. It provides a comprehensive overview of the history of European art and design and includes masterpieces by major artists such as Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Whistler and Dali. The art from non-European cultures includes an internationally renowned collection of Chinese art. The development of the art collections began with the bequest in 1854 of 510 paintings by the Glasgow coachbuilder Archibald McLellan. He was a prolific collector of Italian, Dutch and Flemish art and his bequest included gems such as works by Botticelli and Titian. Other gifts and bequests followed, such as the collection of 70 paintings formed by the portraitist John Graham-Gilbert, which included Rembrandt’s famous Man in Armour. Glasgow’s massive expansion in the late nineteenth century saw the rise of an industrial elite who developed a taste for collecting art. Many were extremely discerning and knowledgeable and their gifts now form the backbone of the art collection. William McInnes, a shipping company owner, had a particular fondness for French art. His bequest in 1944 of over 70 paintings included work by Degas, Monet, Van Gogh, and Picasso. However, the greatest gift undoubtedly came from the shipping magnate Sir William Burrell. His collection of nearly 9,000 objects included a vast array of works of all periods from all over the world, including important medieval tapestries, stained glass, English oak furniture, European paintings and sculpture and important collections of Chinese and Islamic art.