The Lucie Rie Archive at the Crafts Study Centre by Sophie Heath, 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CELSIUS a Peer-Reviewed Bi-Annual Online Journal Supporting the Disciplines of Ceramics, Glass, and Jewellery and Object Design

CELSIUS A peer-reviewed bi-annual online journal supporting the disciplines of ceramics, glass, and jewellery and object design. ISSUE 1 July 2009 Published in Australia in 2009 by Sydney College of the Arts The Visual Arts Faculty The University of Sydney Balmain Road Rozelle Locked Bag 15 Rozelle, NSW 2039 +61 2 9351 1104 [email protected] www.usyd.edu.au/sca Cricos Provider Code: 00026A © The University of Sydney 2009 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the copyright owners. Sydney College of the Arts gratefully acknowledges the contribution of the artists and their agents for permission to reproduce their images and papers. Editor: Jan Guy Publication Layout: Nerida Olson Disclaimers 1. The material in this publication may contain references to persons who are deceased. 2. The artwork and statements in this catalogue have not been classified for viewing purposes and do not represent the views or opinions of the University of Sydney or Sydney College of the Arts. www.usyd.edu.au/sca/research/projects/celsiusjournal CELSIUS A peer-reviewed bi-annual online journal supporting the disciplines of ceramics, glass, and jewellery and object design. Mission Statement The aims of Celsius are to - provide an arena for the publication of scholarly papers concerned with the disciplines of ceramics, glass and jewellery and object design - promote artistic and technical research within these disciplines of the highest standards -foster the research of postgraduate students from Australia and around the world - complement the work being done by professional journals in the exposure of the craft based disciplines -create opportunities of professional experience in the field of publication for USYD postgraduate students Editorial Board The Celsius Editorial Board advises the editor and helps develop and guide the online journal’s publication program. -

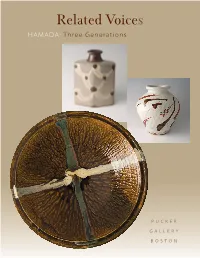

Related Voices Hamada: Three Generations

Related Voices HAMADA: Three Generations PUCKER GALLERY BOSTON Tomoo Hamada Shoji Hamada Bottle Obachi (Large Bowl), 1960-69 Black and kaki glaze with akae decoration Ame glaze with poured decoration 12 x 8 ¼ x 5” 4 ½ x 20 x 20” HT132 H38** Shinsaku Hamada Vase Ji glaze with tetsue and akae decoration Shoji Hamada 9 ¾ x 5 ¼ x 5 ¼” Obachi (Large Bowl), ca. 1950s HS36 Black glaze with trailing decoration 5 ½ x 23 x 23” H40** *Box signed by Shoji Hamada **Box signed by Shinsaku Hamada All works are stoneware. Three Voices “To work with clay is to be in touch with the taproot of life.’’ —Shoji Hamada hen one considers ceramic history in its broadest sense a three-generation family of potters isn’t particularly remarkable. Throughout the world potters have traditionally handed down their skills and knowledge to their offspring thus Wmaintaining a living history that not only provided a family’s continuity and income but also kept the traditions of vernacular pottery-making alive. The long traditions of the peasant or artisan potter are well documented and can be found in almost all civilizations where the generations are to be numbered in the tens or twenties or even higher. In Africa, South America and in Asia, styles and techniques remained almost unaltered for many centuries. In Europe, for example, the earthenware tradition existed from the early Middle Ages to the very beginning of the 20th century. Often carried on by families primarily involved in farming, it blossomed into what we would now call the ‘slipware’ tradition. The Toft family was probably the best known makers of slipware in Staffordshire. -

The Leach Pottery: 100 Years on from St Ives

The Leach Pottery: 100 years on from St Ives Exhibition handlist Above: Bernard Leach, pilgrim bottle, stoneware, 1950–60s Crafts Study Centre, 2004.77, gift of Stella and Nick Redgrave Introduction The Leach Pottery was established in St Ives, Cornwall in the year 1920. Its founders were Bernard Leach and his fellow potter Shoji Hamada. They had travelled together from Japan (where Leach had been living and working with his wife Muriel and their young family). Leach was sponsored by Frances Horne who had set up the St Ives Handicraft Guild, and she loaned Leach £2,500 as capital to buy land and build a small pottery, as well as a sum of £250 for three years to help with running costs. Leach identified a small strip of land (a cow pasture) at the edge of St Ives by the side of the Stennack stream, and the pottery was constructed using local granite. A tiny room was reserved for Hamada to sleep in, and Hamada himself built a climbing kiln in the oriental style (the first in the west, it was claimed). It was a humble start to one of the great sites of studio pottery. The Leach Pottery celebrates its centenary year in 2020, although the extensive programme of events and exhibitions planned in Britain and Japan has been curtailed by the impact of Covid-19. This exhibition is the tribute of the Crafts Study Centre to the history, legacy and continuing significance of The Leach Pottery, based on the outstanding collections and archives relating firstly to Bernard Leach. -

Hans Coper Kindle

HANS COPER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tony Birks | 224 pages | 29 Sep 2013 | Stenlake Publishing | 9781840336221 | English | Ayrshire, United Kingdom Hans Coper PDF Book The two most bankable names in this market are Hans Coper and Lucie Rie and their work can usually be relied on to dominate the top price slots. Coper and Rie worked to create functional wares often co-signing their works. News topics. His works are characterised by their innate tonality and carefully worked surface textures. To ensure you the best experience, we use cookies on our website for technical, analytical and marketing purposes. Site by Artlogic. Coper's work was widely exhibited and collected even in his lifetime. These elements are…. Simply because of their economy and concision, their qualities of distilled expansiveness to border on a contradiction in terms that carries some of the essence of the earliest vessels and figures Cycladic forms are often cited while having a very 20th century consciousness. German-born, Coper initially came to Britain in , and from worked with Lucie Rie in her London studio, moving to Hertfordshire in , and subsequently to Somerset. Invalid Email Address. Vintage Fashion Textiles. A metal alloy made from copper with up to two-thirds tin, often with other small amounts of other metals. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. External Websites. In the first element of a two-part feature, ATG considers the London market. Wright Auction. Waistel Cooper in his own world 04 January Once dismissed as a mere Hans Coper follower, the studio potter is now in rising demand. American Design. Hans Coper — Hans Coper Writer He came to England in but was arrested as an alien and sent to Canada, returning to England in where he enrolled in the Pioneer Corps. -

Lucie Rie - 1902-1995

Lucie Rie - 1902-1995 Dame Lucie Rie [née Gomperz] was born on 16 March 1902 in Vienna, the third and last child of Professor Benjamin Gomperz (1861-1936), an ear, nose, and throat specialist, and his wife, Gisela (1873-1937), daughter of Ignaz Wolf and his wife, Hermine. The Wolfs were a prominent Eisenstadt family whose fortune was based on wine production. The Gomperz family, too, was prosperous and Lucie's childhood was spent between their home in the Falkstrasse and the Wolfs' country house at Eisenstadt. She was educated by a private tutor. Through her father, a friend of Sigmund Freud, and her uncle, the collector and Zionist historian Sandor Wolf, she was also in touch with the rich intellectual life of early twentieth-century Vienna. After contemplating a medical career she decided instead to enter the Kunstgewerbeschule, the art school attached to the Wiener Werkstatte, in 1922. There she was, she said, instantly 'lost' to the potter's wheel. She was taught by Michael Powolny, whose strengths as a ceramist were technical rather than aesthetic. Her work was nevertheless noticed by the co-founder of the Werkstatte, Joseph Hoffmann, who sent her pots to the Exposition des Arts Decoratifs et Modernes in Paris in 1925. Over the next decade she developed her own style. She herself later said in an interview with the author that the work of these years was 'hardly at all important', but critics have disagreed (The Guardian, 31 Aug 1988). She combined a plain, modernist aesthetic with the technical daring that Powolny had encouraged in her, somewhat perversely, by telling her she would never be able to imitate ancient glazes. -

Bernard Leach and British Columbian Pottery: an Historical Ethnography of a Taste Culture

BERNARD LEACH AND BRITISH COLUMBIAN POTTERY: AN HISTORICAL ETHNOGRAPHY OF A TASTE CULTURE by Nora E. Vaillant B. A. Swarthmore College, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Department of Anthropology and Sociology) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia October 2002 © Nora E. Vaillant, 2002 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of J^j'thiA^^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT This thesis presents an historical ethnography of the art world and the taste culture that collected the west coast or Leach influenced style of pottery in British Columbia. This handmade functional style of pottery traces its beginnings to Vancouver in the 1950s and 1960s, and its emergence is embedded in the cultural history of the city during that era. The development of this pottery style is examined in relation to the social network of its founding artisans and its major collectors. The Vancouver potters Glenn Lewis, Mick Henry and John Reeve apprenticed with master potter Bernard Leach in England during the late fifties and early sixties. -

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE October 8, 2014 Conversations with Lucie Rie Conversations with Lucie Rie October 17, 2014 to March 9, 2015 Drury Gallery How incredibly compelling a conversation with famed potter Lucie Rie would have been! Rie, whose life story is as awe-inspiring as her work, will be celebrated at the Art Gallery Curated by Toby Lawrence of Greater Victoria later this month when the exhibition, Conversations with Lucie Rie , opens on Oct. 17. One of the most influential potters of the 20 th century, Rie achieved damehood in 1991, and is renowned for her modernist aesthetic of spare lines and textured surfaces. Her Art Gallery of Greater Victoria career spanned seven decades during the 20th century and culminated in an exhibition at 1040 Moss Street the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1994 to 1995—the year of her death. Rie was born in Vienna in 1902, and she was forced to leave behind a burgeoning arts career when she Victoria, British Columbia V8V 4P1 fled from the Nazis in 1938 to England. In London, Rie re-established herself through her 250.384.4171 aggv.ca own artistic language and studio at Albion Mews. “The exhibition considers the development of Rie’s work and the impact she had on her contemporaries and subsequent generations of artists, curators, collectors, and admirers,” says the exhibition’s curator, Toby Lawrence. “It also highlights the friendships and dialogue she established through her practice as a studio potter.” See aggv.ca for details “The Gallery is extremely fortunate to have 19 of Lucie Rie’s pieces in our collection,” continues Lawrence. -

Emmanuel Cooper Archive

Emmanuel Cooper Archive (COOPER) ©Bishopsgate Institute Catalogued by Stefan Dickers, September 2019 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents p.2 Collection Level Description p.3 COOPER/1: Gay Art Archive p.5 COOPER/2: Art Projects p.88 COOPER/3: Gay Left Archive p.93 COOPER/4: Campaign for Homosexual Equality Papers p.108 COOPER/5: Scrapbooks p.126 COOPER/6: Gay Theatre Archive p.127 COOPER/7: Gay History Group p.131 COOPER/8: Portobello Boys p.132 2 COOPER Emmanuel Cooper Archive 1956-209 Name of Creator: Cooper, Emmanuel (1938-2012) potter and writer on the arts Extent: 28 Boxes and oversize items Administrative/Biographical History: Emmanuel Cooper was born in Pilsley, North East Derbyshire and studied at the University for the Creative Arts. He also achieved a PhD degree at Middlesex University. He was a member of the Crafts Council and the editor of Ceramic Review. Since 1999, he was visiting Professor of Ceramics and Glass at the Royal College of Art. He was the author of many books on ceramics, including his definitive biography of Bernard Leach that was published in 2003 (Yale University Press), and was also the editor of The Ceramics Book, published in 2006. In the early 1970s, he was also a cofounder of the Gay Left collective, and remained a prominent LGBT rights campaigner throughout his life. He also published several studies of LGBT art, including The Sexual Perspective and Fully Exposed: The Male Nude in Photography. As a potter, Cooper's work falls into one of two general forms. In the first his vessels are heavily glazed in a volcanic form. -

Exhibitions and Events

Exhibitions and Events SEPTEMBER 2018 – MARCH 2019 Exhibitions Highlights September 2018 – March 2019 Strata | Rock | Dust | Stars 28 September – 25 November 2018 OF Day of Clay DAY 6 October 2018 The BFG in Pictures 12 October 2018 – 24 February 2019 When all is Quiet: Kaiser Chiefs in CLAY Conversation with York Art Gallery 14 December 2018 – 10 March 2019 Lucie Rie: Ceramics and Buttons Until 12 May 2019 ARTIST’S CHOICE by Per Inge Bjørlo Until 31 March 2019 6 OCTOBER 2018 Project Gallery As part of the Ceramics + Design Now Festival 2018, join York Art Gallery for a celebration of ceramics with Ulungile Magubane, eMBIZENI hands-on activities, performance art, raku firing, workshops and expert talks. From 28 September 2018 Save time and buy your ticket online – visit yorkartgallery.org.uk | 3 Strata | Rock | Dust | Stars A York Museums Trust, FACT Liverpool, and York Mediale exhibition. 28 September – 25 November 2018 This is a landmark exhibition featuring moving image, new media and interactive artwork. Strata - Rock - Dust - Stars takes its inspiration from William Smith’s ground-breaking geological map of England, Wales and Scotland, created in 1815 – which identified the layers of the Earth and transformed the way in which the world was understood. It will be the most ambitious and large-scale media art exhibition York has ever hosted. The exhibition showcases works by internationally renowned artists Isaac Julien, Agnes Meyer-Brandis, Semiconductor, Phil Coy, Liz Orton, David Jacques, and Ryoichi Kurokawa. Co-commissioned between York Art Gallery and York Mediale, and curated by Mike Stubbs, Director of FACT Liverpool. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Art Galleries Committee, 17/02/2021

Public Document Pack Art Galleries Committee Date: Wednesday, 17 February 2021 Time: 9.30 am Venue: Virtual meeting – https://vimeo.com/509986438 Everyone is welcome to attend this committee meeting. The Local Authorities and Police and Crime Panels (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority and Police and Crime Panel Meetings) (England and Wales) Regulations 2020. Under the provisions of these regulations the location where a meeting is held can include reference to more than one place including electronic, digital or virtual locations such as Internet locations, web addresses or conference call telephone numbers. To attend this meeting it can be watched live as a webcast. The recording of the webcast will also be available for viewing after the meeting has ended. Membership of the Art Galleries Committee Councillors - Akbar, Bridges, Craig, Leech, Leese, N Murphy, Ollerhead, Rahman, Richards and Stogia Art Galleries Committee Agenda 1. Urgent Business To consider any items which the Chair has agreed to have submitted as urgent. 2. Appeals To consider any appeals from the public against refusal to allow inspection of background documents and/or the inclusion of items in the confidential part of the agenda. 3. Interests To allow Members an opportunity to [a] declare any personal, prejudicial or disclosable pecuniary interests they might have in any items which appear on this agenda; and [b] record any items from which they are precluded from voting as a result of Council Tax/Council rent arrears; [c] the existence and nature of party whipping arrangements in respect of any item to be considered at this meeting. Members with a personal interest should declare that at the start of the item under consideration. -

Fire + Earth Catalogue

Table of Contents Artists Robert Archambeau ................................................1 Ann Mortimer.....................................................112 Loraine Basque........................................................4 Diane Nasr..........................................................115 Alain Bernard..........................................................7 Ingrid Nicolai......................................................118 Robert Bozak ........................................................10 Agnes Olive.........................................................121 John Chalke ..........................................................13 Walter Ostrom ....................................................124 Ruth Chambers.....................................................16 Kayo O’Young.....................................................127 Victor Cicansky.....................................................19 Greg Payce ..........................................................130 Jennifer Clark........................................................22 Andrea Piller .......................................................133 Bonita Bocanegra Collins ......................................25 Ann Roberts........................................................136 Karen Dahl ...........................................................28 Ron Roy..............................................................139 Roseline Delise......................................................31 Rebecca Rupp .....................................................142 -

Leach Pottery Announce Collaborative Project to Restore Documentary Film Compendium on Bernard Leach and the Mingei Movement

Leach Pottery Announce Collaborative Project to Restore Documentary Film Compendium on Bernard Leach and the Mingei Movement The Leach Pottery and Marty Gross Film Productions, Canada, announce their collaboration in the restoration and re-release of historically important films from the 1930’s to the 1970’s which profile key figures in the history of The Leach Pottery and the Japanese Mingei Movement. The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation have provided a generous £5000 donation in support of this unique project, and following this initial funding further funding has been pledged or received from The Museum of Ceramic Art New York, Ceramica Stiftung Basel, Warren and Nancy MacKenzie, scholar Dr. Paul Griffith and art collector Dr. John Driscoll. Film subjects include Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada, Soetsu Yanagi, Janet Leach, William Marshall and others. Bernard Leach, founder of The Leach Pottery, was an important figure in the history of contemporary ceramics and a key member of the group that founded the Mingei Movement. His writings on Japan and its ceramic traditions are central documents in the history of the Modern craft movement. Over the neXt three years, the project will restore and digitize important and never before seen footage which documents the studies of Bernard Leach and his colleagues in Japan as they developed ideas that became central to the Mingei movement. The resulting compendium will consist of DVDs and a booklet containing the following films and new documentation: ▪ Trip to Japan, filmed by Bernard Leach, 1934-35 ▪ Mashiko Village Pottery, Japan 1937 ▪ Bernard Leach visit to San Francisco, 1950 ▪ The Art of the Potter (1971), by David Outerbridge and Sidney Reichman ▪ Excerpts from 10 hours of unseen film footage from The Art of the Potter ▪ An exclusive Video Interview by Marty Gross with Mihoko Okamura, D.T.