Lucie Rie - 1902-1995

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE October 8, 2014 Conversations with Lucie Rie Conversations with Lucie Rie October 17, 2014 to March 9, 2015 Drury Gallery How incredibly compelling a conversation with famed potter Lucie Rie would have been! Rie, whose life story is as awe-inspiring as her work, will be celebrated at the Art Gallery Curated by Toby Lawrence of Greater Victoria later this month when the exhibition, Conversations with Lucie Rie , opens on Oct. 17. One of the most influential potters of the 20 th century, Rie achieved damehood in 1991, and is renowned for her modernist aesthetic of spare lines and textured surfaces. Her Art Gallery of Greater Victoria career spanned seven decades during the 20th century and culminated in an exhibition at 1040 Moss Street the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1994 to 1995—the year of her death. Rie was born in Vienna in 1902, and she was forced to leave behind a burgeoning arts career when she Victoria, British Columbia V8V 4P1 fled from the Nazis in 1938 to England. In London, Rie re-established herself through her 250.384.4171 aggv.ca own artistic language and studio at Albion Mews. “The exhibition considers the development of Rie’s work and the impact she had on her contemporaries and subsequent generations of artists, curators, collectors, and admirers,” says the exhibition’s curator, Toby Lawrence. “It also highlights the friendships and dialogue she established through her practice as a studio potter.” See aggv.ca for details “The Gallery is extremely fortunate to have 19 of Lucie Rie’s pieces in our collection,” continues Lawrence. -

Exhibitions and Events

Exhibitions and Events SEPTEMBER 2018 – MARCH 2019 Exhibitions Highlights September 2018 – March 2019 Strata | Rock | Dust | Stars 28 September – 25 November 2018 OF Day of Clay DAY 6 October 2018 The BFG in Pictures 12 October 2018 – 24 February 2019 When all is Quiet: Kaiser Chiefs in CLAY Conversation with York Art Gallery 14 December 2018 – 10 March 2019 Lucie Rie: Ceramics and Buttons Until 12 May 2019 ARTIST’S CHOICE by Per Inge Bjørlo Until 31 March 2019 6 OCTOBER 2018 Project Gallery As part of the Ceramics + Design Now Festival 2018, join York Art Gallery for a celebration of ceramics with Ulungile Magubane, eMBIZENI hands-on activities, performance art, raku firing, workshops and expert talks. From 28 September 2018 Save time and buy your ticket online – visit yorkartgallery.org.uk | 3 Strata | Rock | Dust | Stars A York Museums Trust, FACT Liverpool, and York Mediale exhibition. 28 September – 25 November 2018 This is a landmark exhibition featuring moving image, new media and interactive artwork. Strata - Rock - Dust - Stars takes its inspiration from William Smith’s ground-breaking geological map of England, Wales and Scotland, created in 1815 – which identified the layers of the Earth and transformed the way in which the world was understood. It will be the most ambitious and large-scale media art exhibition York has ever hosted. The exhibition showcases works by internationally renowned artists Isaac Julien, Agnes Meyer-Brandis, Semiconductor, Phil Coy, Liz Orton, David Jacques, and Ryoichi Kurokawa. Co-commissioned between York Art Gallery and York Mediale, and curated by Mike Stubbs, Director of FACT Liverpool. -

Hans Coper and Pupils Press Release

Hans Coper, Lucie Rie & Pupils Hans Coper, Spade Form (1967) height 19 cms. Image: Michael Harvey Influential potter Hans Coper (1920-1981) was a champion of arts education. “His teaching had the same integrity and strength as had his pots; graceful, direct, precisely and sensitively tuned...” 1 In this his centenary year, Oxford Ceramics Gallery celebrate this element of Coper’s work with their forthcoming exhibition Hans Coper, Lucie Rie and Pupils (15th May - 4th July) A leader in the development of ceramics in the twentieth century Coper taught at Camberwell and then at Royal College of Art alongside his own teacher and mentor Lucie Rie (1902 - 1995). 1 Tony Birks. Hans Coper. (New York: Harper & Row, 1983), 61. Group of works by Lucie Rie on shelf including Bronze Vase (central) alongside a coffee pot and jug with white glaze and pulled handles. Newly sourced examples of Coper’s work are shown alongside fine examples from Lucie Rie and key works from the following generation of their pupils who went on to define the range and creative brilliance of British Studio Pottery. Exhibitors in- clude: Alison Britton, Elizabeth Fritsch, Ian Godfrey, Ewen Henderson, Jacqueline Poncelet & John Ward. Alison Britton, White Jar (1991) 34 x 46 x 19.5 cm. image: James Fordham. Born in Chemnitz, Germany, Hans Coper (1920-1981) came to England in 1939 as an engineering student and in 1946 he began working as an assistant to the Austrian potter Lucie Rie (1902-1995) in her studio in London, taking him on with no formal training in ceramics. -

Fritsch E Biography

Elizabeth Fritsch CBE Curriculum Vitae Born 1940, Wales 1958-1964 Birmingham School of Music & Royal Academy of Music, London 1968-1971 Royal College of Art, London, MA Ceramics Working in London Museums and collectors across the world have been admirers of Elizabeth Fritsch's work for decades. Her hand-built fore-shortened forms combined with rhythmic patterns are signatures that are widely-recognised and inspired by her training as a classical musician before turning to ceramics. Works are often grouped together and juxtaposed so that the rear or side of a vase balances or provides a counterpoint to a neighbour. Having graduated from the Royal College of Art, London in 1971, Elizabeth is regarded as one of the UK's leading ceramic artists. Elizabeth Fritsch -2 - Selected Solo Exhibitions 2010 Dynamic Structures: Painted Vessels, National Museum Cardiff, Wales, in association with Adrian Sassoon 2008 The Fine Art Society, London 2007 Anthony Hepworth Fine Art, Bath 2000 Memory of Architecture, Part II, Galerie Besson, London Metaphysical Vessels, Mobilia Gallery, Cambridge, USA 1998 Sea Pieces, Contemporary Applied Arts, London 1995-1996 Metaphysical Pots, Museum Bellerive, Zurich, Switzerland & tour to Munich, Halle & Karlsruhe, Germany 1994 Order and Chaos, Bellas Artes, Santa Fe, USA Osiris Gallery, Brussels 1993-1995 Vessels from Another World, (retrospective) Northern Centre for Contemporary Art, Sunderland & tour to Aberdeen, Birmingham, Cardiff, London, Norwich 1992-1993 Pilscheur Fine Art, London, (retrospective) 1990-1991 Hetjens -

Southern Discomfort Memories Pi2

AJR Information Volume L No. 8 August 1995 £3 (to non-members) Don't miss ... Populists, terrorists and revisionists Is Guinness good for you? p5 Mid-Thirties Southern discomfort memories pi2 King Oedipus in hen a country's body politic goes rotten underdevelopment and maladministration. Haider Austria p/6 . the process has to start somewhere, and prospers because of the feeble denazification of Aus W this starting point is surprisingly often in tria, itself the result of the ludicrous Allied the South. While Berlin was still the capital of misconception that Hitler's birthplace was his first Weimar Germany, Munich was already Hauptstadt victim. Currently Austria is also the detection-proof A der Bewegung. Le Pen has captured three town halls hideaway of the murderous Bavarian Liberation along the Riviera; the Italian Neo-Fascists are Army {Bajuvarische Befreiungsarmee) - so called waming! strongest South of Rome; the biggest vote for a because they deny the existence of a separate Aus Fourth German Reich has been cast in Austria, trian nation - who target gypsies and liberal he uncer where Haider conjures up another Anschluss. politicians. tainty Geography has little to do with it. Interwar How does the UK fit into this overall picture? Is T surrounding Bavaria spawned Nazism in exaggerated reaction to there a danger of the British body politic putrefying the recent Austrian the left-wing Rdterepublik of 1919. Le Pen's success from a starting point in the South? Not on present compensation law in the South of France stems from de Gaulle's with showing - but complacency is a poor counsellor. -

Masterpieces of Modern Studio Ceramics

Masterpieces of Modern Studio Ceramics Ceramics is having a bit of a moment. Last year alone featured exhibitions such as: Things of Beauty Growing: British Studio Pottery at the Yale Center for British Art, opening at The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, this March, That Continuous Thing at Tate St Ives, Clare Twomey’s Factory installation take-over at Tate Exchange, Keith Harrison’s Joyride spectacle for Jerwood Open Forest Commission, as well as the incredibly successful British Ceramics Biennale, Stoke-on-Trent. The profile of British studio ceramics is growing, presenting the perfect opportunity to celebrate the relationship between studio ceramic practice and British modernism. Beginning in the early 20th century, the British studio ceramics movement reinvigorated a long- standing tradition of making objects from clay, by hand. These objects span familiar forms, such as domestic functional vessels, to abstract and non-functional, often sculptural, forms. Sitting at the heart of Crafts Council Collections, British studio ceramics provide a cross-generational narrative of innovation, invention and tradition. Featuring works from the Crafts Council, The Fitzwilliam Museum and three specialist UK galleries, this display presents nearly 90 years of practice, and features functional, sculptural, abstract and figurative forms, presenting a snapshot of work and makers to inspire. Annabelle Campbell and Helen Ritchie (curators) THE GALLERIES: Erskine Hall and Coe Marsden Woo Gallery Oxford Ceramics Gallery 15 Royal Arcade 229 Ebury Street 29 -

Hans Coper – (1920 – 1981)

HANS COPER – (1920 – 1981) Hans Coper was among the artists who fled Hitler’s Germany in the late 1930’s and settled in England. Employment in the ceramic button workshop of fellow refugee Lucie Rie resulted in both his introduction to ceramic art, which would become his life’s work, and a close friendship with Rie that would be mutually supportive and enriching. Coper and Rie worked together at her studio until 1958 when Coper set out on his own. By that time he was already a recognized potter, but in the years to come his style would mature and he would become one of the major figures of twentieth century ceramics. His stoneware vessels were wheel-thrown and then altered and assembled and finished with oxides, slips and textures. The pieces are sculptural, not functional, but are always vessels reflecting Coper’s commitment to what he called the essence of the clay. Hans Coper’s work and life were cut short by the onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in 1975 which diminished his ability to work and ultimately took his life in 1981. “Although Lucie Rie outlived Hans Coper by fourteen years, and the aims of modern potters were reshaped in this period, no one has come forward to take their place, especially the place of Hans. He combined originality with an uncompromising search for excellence, and his legacy of work is his memorial.”1 1. Tony Birks. Hans Coper. (New York: Harper & Row, 1983), 79. ARTIST’S STATEMENT – HANS COPER “My concern is with extracting essences rather than with experiment and exploration. -

Dan Flavin, to Lucie Rie and Hans Coper, Master Potters December 19, 2017 — February 4, 2018 Vito Schnabel Gallery, St

Dan Flavin, to Lucie Rie and Hans Coper, master potters December 19, 2017 — February 4, 2018 Vito Schnabel Gallery, St. Moritz Installation view, Dan Flavin, to Lucie Rie and Hans Coper, master potters, Vito Schnabel Gallery, St. Moritz © Stephen Flavin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Courtesy Vito Schnabel Gallery; Photo by Stefan Altenburger St. Moritz, Switzerland Beginning December 19, Vito Schnabel Gallery will present Dan Flavin, to Lucie Rie and Hans Coper, master potters, the first exhibition to bring together the work of artist Dan Flavin, renowned for his work with fluorescent light, and acclaimed European ceramicists Lucie Rie (1902–1995) and Hans Coper (1920–1981). Eighteen significant light works from Flavin’s two 1990 series dedicated to the Vienna-born Rie and her German-born protégé Coper, respectively, will be shown in juxtaposition with a group of fifteen vessels from his personal collection of objects by the London-based potters. Organized in collaboration with Stephen Flavin, President of the Dan Flavin Estate, the exhibition has been conceived to explore affinities between three artists who employed dramatically different mediums to establish and redefine space, and to investigate issues of materiality, harmony, and permanence. On view through February 4, 2018, Dan Flavin, to Lucie Rie and Hans Coper, master potters marks the beginning of an ongoing collaboration planned by Vito Schnabel Gallery and the Dan Flavin Estate. The exhibition will be accompanied by an illustrated catalogue featuring essays by curator and art historian Marianne Stockebrand, and Jenni Sorkin, art historian, critic, and Associate Professor of Contemporary Art History at the University of California, Santa Barbara. -

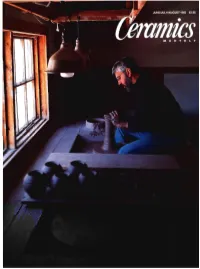

Herefore Greater Value (I.E., Theexhibitions Reflect This Event Everywhere

June/July/August 1995 1 Spencer L. DavisPublisher and Acting Editor Ruth C. Butler........................Associate Editor Kim Nagorski........................ Assistant Editor Tess Galvin...........................Editorial Assistant Randy Wax....................................Art Director Mary Rushley....................Circulation Manager Mary E. Beaver .... Assistant Circulation Manager Connie Belcher................Advertising Manager Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Post Office Box 12788 Columbus, Ohio 43212-0788 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly {ISSN 0009-0328) is published monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc., 1609 Northwest Boulevard, Columbus, Ohio 43212-0788. Second Class post age paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscrip tions outside the U.S.A. In Canada, add GST (registration number R123994618). Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Department, Post Office Box 12788, Columbus, Ohio 43212-0788. Contributors: Manuscripts, announcements, news releases, photographs, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustrations and digital TIFF or EPS images are welcome and will be considered for publication. Mail submis sions to Ceramics Monthly, PostOffice Box 12788, Columbus, Ohio 43212-0788. We also accept unillustrated materials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines:Printed information on standards and procedures for submitting materials is available upon request. Indexing:An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Additionally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) index ing is available through Wilsonline, 950 Univer sity Avenue, Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Company, 362 Lakeside Drive, Forest City, California 94404. -

Henry Rothschild and Primavera: the Retail, Exhibition and Collection of Craft in Post-War Britain, 1945-1980

Citation: Barker, Janine (2015) Henry Rothschild and Primavera: The retail, exhibition and collection of craft in post-war Britain, 1945-1980. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/30325/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html HENRY ROTHSCHILD AND PRIMAVERA: THE RETAIL, EXHIBITION AND COLLECTION OF CRAFT IN POST- WAR BRITAIN, 1945 - 1980 JANINE BARKER PhD 2015 1 2 HENRY ROTHSCHILD AND PRIMAVERA: THE RETAIL, EXHIBITION AND COLLECTION OF CRAFT IN POST- WAR BRITAIN, 1945 – 1980 JANINE BARKER A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences and in collaboration with the Shipley Art Gallery, Gateshead December 2015 3 4 Abstract An AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Award has made collaboration possible between Northumbria University and the Shipley Art Gallery, Gateshead in providing the opportunity to highlight a significant narrative in craft history. -

Kunsthaus Graz English

Kunsthaus Graz English Kneaded Knowledge The Language of Ceramics 25.09.2016 – 19.02.2017 Space01 Kunsthaus Graz, Universalmuseum Joanneum Lendkai 1, 8020 Graz T +43–(0)316/8017–9200, Tue–Sun 10am–5pm [email protected], www.kunsthausgraz.at This text is published on the occasion of the exhibition Some of the earliest artefacts to be Kneaded Knowledge made were ceramics, prized since time The Language of Ceramics immemorial both for their usefulness Kunsthaus Graz Universalmuseum Joanneum and their aesthetic appeal. Today, while September 25, 2016 until February 19, 2017 pots are still produced from this ancient material, the way in which it is handled is constantly being changed and reinter- preted. Ai Weiwei and Edmund de Waal both have a long and deep preoccupa- tion with this material—and yet their artistic approaches are very different. At the Kunsthaus Graz, the two artists act as curators and artistic partners in the exhibition. Through a highly personal view, they reveal the broad diversity of ceramics. Meissen Early Asian Ceramics Ai Weiwei symbolic of this. The work Stones was commissioned in 2011 by the The white tea service at the The display of early Asian ceram- Artist and actionist Ai Weiwei is Universalmuseum Joanneum, and beginning of the exhibition ics was chosen by Chinese artist one of China’s most renowned and shows casts of stone age archaeo- appears a little wonky and less Ai Weiwei. He himself collects respected contemporary artists. A logical finds. These have been than perfect, yet it still has some- these ancient witnesses to a dis- continuous exploration of Chinese discovered since 1947 in the Rep- thing wonderful about it. -

De Waal E Photo

Edmund de Waal Curriculum Vitae Born in1964, Nottingham 1985 Trinity Hall Scholarship 1986 Trinity Hall, Cambridge (B.A. Hons English Literature) 1992 Sheffield University, Sheffield (Post Graduate Diploma in Japanese Language) 1991 - 1993 Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation Scholarship 2000 - 2002 Senior Research Fellow in Ceramics, University of Westminster Working in London “De Waal's art speaks to his enduring fascination with the nature of objects and the attendant history of their collection and display. His poignant memoir The Hare with Amber Eyes (2010) is a family biography whose recurring motif through five generations is a large collection of netsuke. A potter since childhood and an acclaimed writer, de Waal’s studies of the history of ceramics have taken him from ancient Japan to late modernism. He confronts European and Asian traditions of intimate craftsmanship with the scale and sequence of minimalist art and music. De Waal's desire to transcend utilitarian pottery was evident in his transition during the 1980s from clay to more refined porcelain, a medium that demands acute focus of mind and eye as well as a swift hand. A new audacity is expressed in the sheer number of pots and their arrangement. Impact is achieved through scale and multiplicity, yet the subtle iterations of the handmade process are maintained.” From the catalogue of Edmund de Waal: Atemwende, 2013 Edmund de Waal - 2 - Selected Solo Exhibitions 2017 Morandi / Edmund de Waal, Artipelag, Stockholm, Sweden Letrres de Londres, Espace Muraille, Geneva, Switzerland