A Model Humanitarian Intervention? Reassessing NATO's Libya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africa Yearbook

AFRICA YEARBOOK AFRICA YEARBOOK Volume 10 Politics, Economy and Society South of the Sahara in 2013 EDITED BY ANDREAS MEHLER HENNING MELBER KLAAS VAN WALRAVEN SUB-EDITOR ROLF HOFMEIER LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 ISSN 1871-2525 ISBN 978-90-04-27477-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-90-04-28264-3 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents i. Preface ........................................................................................................... vii ii. List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................... ix iii. Factual Overview ........................................................................................... xiii iv. List of Authors ............................................................................................... xvii I. Sub-Saharan Africa (Andreas Mehler, -

A Strategy for Success in Libya

A Strategy for Success in Libya Emily Estelle NOVEMBER 2017 A Strategy for Success in Libya Emily Estelle NOVEMBER 2017 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE © 2017 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, 501(c)(3) educational organization and does not take institutional positions on any issues. The views expressed here are those of the author(s). Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................1 Why the US Must Act in Libya Now ............................................................................................................................1 Wrong Problem, Wrong Strategy ............................................................................................................................... 2 What to Do ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Reframing US Policy in Libya .................................................................................................. 5 America’s Opportunity in Libya ................................................................................................................................. 6 The US Approach in Libya ............................................................................................................................................ 6 The Current Situation -

Selected Practice of the UN Security

SELECTED PRACTISE OF THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL IN RELATION TO THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT AND THE ROME STATUTE SYSTEM (1998-2012) 3nd Update: 10 October 2012 Contents: 1. Highlights on the fight against impunity through referrals by the Security Council under Article 13 of the Rome Statute ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Côte d’Ivoire .................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Darfur, Sudan ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Democratic Republic of the Congo .................................................................................................. 5 1.4 Gaza ................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.5 Kenya ............................................................................................................................................... 5 1.6 Libya ................................................................................................................................................ 6 1.7 Mali .................................................................................................................................................. 6 1.8 Myanmar/Burma ............................................................................................................................. -

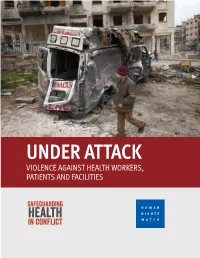

Under Attack

UNDER ATTACK V IOLEN CE A GA INST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Safeguarding HUMAN Health RIGHTS in Conflict WATCH (front cover) A Syrian youth walks past a destroyed ambulance in the Saif al-Dawla district of the war-torn northern city of Aleppo on January 12, 2013. © 2013 JM Lopez/AFP/Getty Images UNDER ATTACK VIOLENCE AGAINST HEALTH WORKERS, PATIENTS AND FACILITIES Overview of Recent Attacks on Health Care ...........................................................................................2 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................5 Urgent Actions Needed .......................................................................................................................7 Polio Vaccination Campaign Workers Killed ..........................................................................................8 Nigeria and Pakistan ......................................................................................................................8 Emergency Care Outlawed .................................................................................................................10 Turkey ..........................................................................................................................................10 Health Workers Arrested, Imprisoned ................................................................................................12 Bahrain ........................................................................................................................................12 -

Violent Extremism and Insurgency in Libya: a Risk Assessment

VIOLENT EXTREMISM AND INSURGENCY IN LIBYA: A RISK ASSESSMENT JULY 1, 2013 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Guilain Denoeux, Management Systems International. VIOLENT EXTREMISM AND INSURGENCY IN LIBYA: A RISK ASSESSMENT Contracted under AID-OAA-TO-11-00051 Democracy and Governance and Peace and Security in the Asia and Middle East This paper was written by Dr. Guilain Denoeux, Professor of Government at Colby College and Senior Associate at Management Systems International. Dr. Denoeux is an expert on the comparative politics of the Middle East, democratization and violent extremism, and co-authored (with Dr. Lynn Carter) the USAID Guide to the Drivers of Violent Extremism (2009). DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS Acronyms .................................................................................................................................... i Map ........................................................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary....................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 4 Spring 2012-Spring 2013 VE Highlights -

If Our Men Won't Fight, We Will"

“If our men won’t ourmen won’t “If This study is a gender based confl ict analysis of the armed con- fl ict in northern Mali. It consists of interviews with people in Mali, at both the national and local level. The overwhelming result is that its respondents are in unanimous agreement that the root fi causes of the violent confl ict in Mali are marginalization, discrimi- ght, wewill” nation and an absent government. A fact that has been exploited by the violent Islamists, through their provision of services such as health care and employment. Islamist groups have also gained support from local populations in situations of pervasive vio- lence, including sexual and gender-based violence, and they have offered to restore security in exchange for local support. Marginality serves as a place of resistance for many groups, also northern women since many of them have grievances that are linked to their limited access to public services and human rights. For these women, marginality is a site of resistance that moti- vates them to mobilise men to take up arms against an unwilling government. “If our men won’t fi ght, we will” A Gendered Analysis of the Armed Confl ict in Northern Mali Helené Lackenbauer, Magdalena Tham Lindell and Gabriella Ingerstad FOI-R--4121--SE ISSN1650-1942 November 2015 www.foi.se Helené Lackenbauer, Magdalena Tham Lindell and Gabriella Ingerstad "If our men won't fight, we will" A Gendered Analysis of the Armed Conflict in Northern Mali Bild/Cover: (Helené Lackenbauer) Titel ”If our men won’t fight, we will” Title “Om våra män inte vill strida gör vi det” Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--4121—SE Månad/Month November Utgivningsår/Year 2015 Antal sidor/Pages 77 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Utrikes- & Försvarsdepartementen Forskningsområde 8. -

Bibliography: Boko Haram

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 13, Issue 3 Bibliography: Boko Haram Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes [Bibliographic Series of Perspectives on Terrorism – BSPT-JT-2019-5] Abstract This bibliography contains journal articles, book chapters, books, edited volumes, theses, grey literature, bibliog- raphies and other resources on the Nigerian terrorist group Boko Haram. While focusing on recent literature, the bibliography is not restricted to a particular time period and covers publications up to May 2019. The literature has been retrieved by manually browsing more than 200 core and periphery sources in the field of Terrorism Stud- ies. Additionally, full-text and reference retrieval systems have been employed to broaden the search. Keywords: bibliography, resources, literature, Boko Haram, Islamic State West Africa Province, ISWAP, Abu- bakar Shekau, Abu Musab al-Barnawi, Nigeria, Lake Chad region NB: All websites were last visited on 18.05.2019. - See also Note for the Reader at the end of this literature list. Bibliographies and other Resources Benkirane, Reda et al. (2015-): Radicalisation, violence et (in)sécurité au Sahel. URL: https://sahelradical.hy- potheses.org Bokostan (2013, February-): @BokoWatch. URL: https://twitter.com/BokoWatch Campbell, John (2019, March 1-): Nigeria Security Tracker. URL: https://www.cfr.org/nigeria/nigeria-securi- ty-tracker/p29483 Counter Extremism Project (CEP) (n.d.-): Boko Haram. (Report). URL: https://www.counterextremism.com/ threat/boko-haram Elden, Stuart (2014, June): Boko Haram – An Annotated Bibliography. Progressive Geographies. URL: https:// progressivegeographies.com/resources/boko-haram-an-annotated-bibliography Hoffendahl, Christine (2014, December): Auf der Suche nach einer Strategie gegen Boko Haram. [In search for a strategy against Boko Haram]. -

International Medical Corps in Libya from the Rise of the Arab Spring to the Fall of the Gaddafi Regime

International Medical Corps in Libya From the rise of the Arab Spring to the fall of the Gaddafi regime 1 International Medical Corps in Libya From the rise of the Arab Spring to the fall of the Gaddafi regime Report Contents International Medical Corps in Libya Summary…………………………………………… page 3 Eight Months of Crisis in Libya…………………….………………………………………… page 4 Map of International Medical Corps’ Response.…………….……………………………. page 5 Timeline of Major Events in Libya & International Medical Corps’ Response………. page 6 Eastern Libya………………………………………………………………………………....... page 8 Misurata and Surrounding Areas…………………….……………………………………… page 12 Tunisian/Libyan Border………………………………………………………………………. page 15 Western Libya………………………………………………………………………………….. page 17 Sirte, Bani Walid & Sabha……………………………………………………………………. page 20 Future Response Efforts: From Relief to Self-Reliance…………………………………. page 21 International Medical Corps Mission: From Relief to Self-Reliance…………………… page 24 International Medical Corps in the Middle East…………………………………………… page 24 International Medical Corps Globally………………………………………………………. Page 25 Operational data contained in this report has been provided by International Medical Corps’ field teams in Libya and Tunisia and is current as of August 26, 2011 unless otherwise stated. 2 3 Eight Months of Crisis in Libya Following civilian demonstrations in Tunisia and Egypt, the people of Libya started to push for regime change in mid-February. It began with protests against the leadership of Colonel Muammar al- Gaddafi, with the Libyan leader responding by ordering his troops and supporters to crush the uprising in a televised speech, which escalated the country into armed conflict. The unrest began in the eastern Libyan city of Benghazi, with the eastern Cyrenaica region in opposition control by February 23 and opposition supporters forming the Interim National Transitional Council on February 27. -

ISIS in Libya: a Major Regional and International Threat

המרכז למורשת המודיעין (מל"מ) מרכז המידע למודיעין ולטרור January 2016 ISIS in Libya: a Major Regional and International Threat ISIS operatives enter the coastal city of Sirte in north-central Libya on February 18, 2015, in a show of strength accompanied by dozens of vehicles (Twitter.com, Nasher.me). Since then ISIS has established itself in Sirte and the surrounding areas, turning the entire region into its Libyan stronghold and a springboard for spreading into other regions. Overview 1. In 2015 ISIS established two strongholds beyond the borders of its power base in Iraq and Syria: the first in the Sinai Peninsula, where it wages determined fighting against the Egyptian security forces. The second is situated in the north- central Libyan city of Sirte and its surroundings, where it has established territorial control and from where it seeks to take over the entire country. It intends to turn Libya into a springboard for terrorism and the subversion of the rest of North Africa, the sub-Saharan countries, and southern Europe. The firm territorial base ISIS constructed in Libya is the only one outside IraQ and Syria, and is potentially a greater regional and international threat. 2. ISIS could establish itself in Libya because of the chaos prevalent after the execution of Muammar Qaddafi. As in Iraq and Syria, the governmental-security vacuum created by the collapse of the central government was filled by nationalist and Islamist organizations, local and regional tribal militias and jihadist organizations. The branch of ISIS in Libya exploited the lack of a functioning government and 209-15 2 the absence of international intervention to establish itself in the region around Sirte and from there to aspire to spread throughout Libya. -

Human Rights Watch All Rights Reserved

HUMAN RIGHTS Delivered Into Enemy Hands US-Led Abuse and Rendition of Opponents to Gaddafi’s Libya WATCH Delivered Into Enemy Hands US-Led Abuse and Rendition of Opponents to Gaddafi’s Libya Copyright © 2012 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-940-2 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2012 ISBN: 1-56432-940-2 Delivered Into Enemy Hands US-Led Abuse and Rendition of Opponents to Gaddafi’s Libya Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations.................................................................................................................... -

Libya: Unrest and U.S

Libya: Unrest and U.S. Policy Christopher M. Blanchard Analyst in Middle Eastern Affairs September 9, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33142 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Libya: Unrest and U.S. Policy Summary Muammar al Qadhafi’s 40 years of authoritarian rule in Libya have effectively come to an end. The armed uprising that began in February 2011 has reached a turning point, and opposition forces now control the capital city, Tripoli, in addition to the eastern and western areas of the country. Most observers doubt the rebel gains are reversible. However, the coastal city of Sirte and some parts of central and southern Libya remain contested, and, isolated groups of pro- Qadhafi forces remain capable of armed resistance. The U.S. military continues to participate in Operation Unified Protector, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military operation to enforce United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, which authorizes “all necessary measures” to protect Libyan civilians. As of September 9, Muammar al Qadhafi had not been located or detained, and opposition Transitional National Council (TNC) leaders are urging their forces to exercise restraint and caution so that Qadhafi, his family members, and key regime officials may be captured alive, formally charged, and put to trial. The Libyan people, their interim Transitional National Council, and the international community are shifting their attention from the immediate struggle with the remnants of Qadhafi’s regime to the longer-term challenges of establishing and maintaining security, preventing criminality and reprisals, restarting Libya’s economy, and beginning a political transition. -

Ghosts of the Past: the Muslim Brotherhood and Its Struggle for Legitimacy in Post‑Qaddafi Libya

Ghosts of the Past: The Muslim Brotherhood and its Struggle for Legitimacy in post‑Qaddafi Libya Inga Kristina Trauthig ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author of this paper is Inga Kristina Trauthig. She wishes to thank Emaddedin Badi for his review and invaluable comments and feedback. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own. CONTACT DETAILS For questions, queries and additional copies of this report, please contact: ICSR King’s College London Strand London WC2R 2LS United Kingdom T. +44 20 7848 2098 E. [email protected] Twitter: @icsr_centre Like all other ICSR publications, this report can be downloaded free of charge from the ICSR website at www.icsr.info. © ICSR 2018 Rxxntxxgrxxtxxng ISIS Sxxppxxrtxxrs xxn Syrxx: Effxxrts, Prxxrxxtxxs xxnd Chxxllxxngxxs Table of Contents Key Terms and Acronyms 2 Executive Summary 3 1 Introduction 5 2 The Muslim Brotherhood in Libya pre-2011 – Persecuted, Demonised and Dominated by Exile Structures 9 3 The Muslim Brotherhood’s Role During the 2011 Revolution and the Birth of its Political Party – Gaining a Foothold in the Country, Shrewd Political Manoeuvring and Punching above its Weight 15 4 The Muslim Brotherhood’s Quest for Legitimacy in the Libyan Political Sphere as the “True Bearer of Islam” 23 5 Conclusion 31 Notes and Bibliography 35 1 Key Terms and Acronyms Al-tajammu’-u al-watanī – Arabic for National Gathering or National Assembly GNA – Government of National Accord GNC – General National Council Hizb al-Adala wa’l-Tamiyya – JCP in Arabic HSC – High State Council Ikhwān – Arabic for