Violent Extremism and Insurgency in Libya: a Risk Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations A/HRC/17/44

United Nations A/HRC/17/44 General Assembly Distr.: General 12 January 2012 Original: English Human Rights Council Seventeenth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situation that require the Council’s attention Report of the International Commission of Inquiry to investigate all alleged violations of international human rights law in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya* Summary Pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution S-15/1 of 25 February 2011, entitled “Situation of human rights in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya”, the President of the Human Rights Council established the International Commission of Inquiry, and appointed M. Cherif Bassiouni as the Chairperson of the Commission, and Asma Khader and Philippe Kirsch as the two other members. In paragraph 11 of resolution S-15/1, the Human Rights Council requested the Commission to investigate all alleged violations of international human rights law in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, to establish the facts and circumstances of such violations and of the crimes perpetrated and, where possible, to identify those responsible, to make recommendations, in particular, on accountability measures, all with a view to ensuring that those individuals responsible are held accountable. The Commission decided to consider actions by all parties that might have constituted human rights violations throughout Libya. It also considered violations committed before, during and after the demonstrations witnessed in a number of cities in the country in February 2011. In the light of the armed conflict that developed in late February 2011 in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya and continued during the Commission‟s operations, the Commission looked into both violations of international human rights law and relevant provisions of international humanitarian law, the lex specialis that applies during armed conflict. -

Libya: Unrest and U.S

Libya: Unrest and U.S. Policy Christopher M. Blanchard Analyst in Middle Eastern Affairs September 9, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33142 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Libya: Unrest and U.S. Policy Summary Muammar al Qadhafi’s 40 years of authoritarian rule in Libya have effectively come to an end. The armed uprising that began in February 2011 has reached a turning point, and opposition forces now control the capital city, Tripoli, in addition to the eastern and western areas of the country. Most observers doubt the rebel gains are reversible. However, the coastal city of Sirte and some parts of central and southern Libya remain contested, and, isolated groups of pro- Qadhafi forces remain capable of armed resistance. The U.S. military continues to participate in Operation Unified Protector, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military operation to enforce United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, which authorizes “all necessary measures” to protect Libyan civilians. As of September 9, Muammar al Qadhafi had not been located or detained, and opposition Transitional National Council (TNC) leaders are urging their forces to exercise restraint and caution so that Qadhafi, his family members, and key regime officials may be captured alive, formally charged, and put to trial. The Libyan people, their interim Transitional National Council, and the international community are shifting their attention from the immediate struggle with the remnants of Qadhafi’s regime to the longer-term challenges of establishing and maintaining security, preventing criminality and reprisals, restarting Libya’s economy, and beginning a political transition. -

Libya's Civil War, 2011

Factsheet : Libya’s Civil War, 2011 Factsheet Series No. 123, Created: May 2011, Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East What triggered protests in Libya in early 2011? Protests in Libya began on January 14, in the eastern town of al-Bayda over housing conditions. 1 The February 15 arrest of a human rights activist representing the families of victims of the Abu Salim prison massacre (see below) sparked protests by 500-600 people February 16 in the city of Benghazi, also in eastern Libya. On February 17, police killed 15 Benghazi protesters during a large organized protest. The army’s elite 32 nd Brigade, commanded by Muammar Gaddafi’s son Khamis, swept into Bayda and Benghazi February 17-18, killing dozens of people, sparking outrage and even larger protests. Protesters’ initial demands then morphed into calls for Gaddafi’s ouster. Benghazi remains a rebel stronghold. What are the protesters’ larger grievances? Regional disparities in the distribution of the benefits of oil revenues. Although most of Libya’s proven oil and gas reserves lie in eastern Libya, it has long been neglected in favour of the western province around Tripoli, the capital. According to a leaked US embassy cable, Gaddafi deliberately pursued policies to “keep the east poor.” Half of the men aged 18 to 34 in eastern Libya are unemployed, according to a local source quoted in the cable. 2 Periodic uprisings in eastern Libya have also been sharply suppressed over the years, intensifying resentment of Gaddafi there.3 Gross human rights violations. Gaddafi’s Libya has a history of gross human rights violations which remain unpunished and largely unacknowledged by the government. -

Ghosts of the Past: the Muslim Brotherhood and Its Struggle for Legitimacy in Post‑Qaddafi Libya

Ghosts of the Past: The Muslim Brotherhood and its Struggle for Legitimacy in post‑Qaddafi Libya Inga Kristina Trauthig ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author of this paper is Inga Kristina Trauthig. She wishes to thank Emaddedin Badi for his review and invaluable comments and feedback. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own. CONTACT DETAILS For questions, queries and additional copies of this report, please contact: ICSR King’s College London Strand London WC2R 2LS United Kingdom T. +44 20 7848 2098 E. [email protected] Twitter: @icsr_centre Like all other ICSR publications, this report can be downloaded free of charge from the ICSR website at www.icsr.info. © ICSR 2018 Rxxntxxgrxxtxxng ISIS Sxxppxxrtxxrs xxn Syrxx: Effxxrts, Prxxrxxtxxs xxnd Chxxllxxngxxs Table of Contents Key Terms and Acronyms 2 Executive Summary 3 1 Introduction 5 2 The Muslim Brotherhood in Libya pre-2011 – Persecuted, Demonised and Dominated by Exile Structures 9 3 The Muslim Brotherhood’s Role During the 2011 Revolution and the Birth of its Political Party – Gaining a Foothold in the Country, Shrewd Political Manoeuvring and Punching above its Weight 15 4 The Muslim Brotherhood’s Quest for Legitimacy in the Libyan Political Sphere as the “True Bearer of Islam” 23 5 Conclusion 31 Notes and Bibliography 35 1 Key Terms and Acronyms Al-tajammu’-u al-watanī – Arabic for National Gathering or National Assembly GNA – Government of National Accord GNC – General National Council Hizb al-Adala wa’l-Tamiyya – JCP in Arabic HSC – High State Council Ikhwān – Arabic for -

Origins of the Libyan Conflict and Options for Its Resolution

ORIGINS OF THE LIBYAN CONFLICT AND OPTIONS FOR ITS RESOLUTION JONATHAN M. WINER MAY 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-12 CONTENTS * 1 INTRODUCTION * 4 HISTORICAL FACTORS * 7 PRIMARY DOMESTIC ACTORS * 10 PRIMARY FOREIGN ACTORS * 11 UNDERLYING CONDITIONS FUELING CONFLICT * 12 PRECIPITATING EVENTS LEADING TO OPEN CONFLICT * 12 MITIGATING FACTORS * 14 THE SKHIRAT PROCESS LEADING TO THE LPA * 15 POST-SKHIRAT BALANCE OF POWER * 18 MOVING BEYOND SKHIRAT: POLITICAL AGREEMENT OR STALLING FOR TIME? * 20 THE CURRENT CONFLICT * 22 PATHWAYS TO END CONFLICT SUMMARY After 42 years during which Muammar Gaddafi controlled all power in Libya, since the 2011 uprising, Libyans, fragmented by geography, tribe, ideology, and history, have resisted having anyone, foreigner or Libyan, telling them what to do. In the process, they have frustrated the efforts of outsiders to help them rebuild institutions at the national level, preferring instead to maintain control locally when they have it, often supported by foreign backers. Despite General Khalifa Hifter’s ongoing attempt in 2019 to conquer Tripoli by military force, Libya’s best chance for progress remains a unified international approach built on near complete alignment among international actors, supporting Libyans convening as a whole to address political, security, and economic issues at the same time. While the tracks can be separate, progress is required on all three for any of them to work in the long run. But first the country will need to find a way to pull back from the confrontation created by General Hifter. © The Middle East Institute The Middle East Institute 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. -

416 Kb, 82 Pages

January 2006 Volume 18, No. 1(E) Words to Deeds The Urgent Need for Human Rights Reform I. Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Methodology............................................................................................................................. 5 III. Recommendations.................................................................................................................. 7 Regarding the People’s Court ................................................................................................. 7 Regarding the Death Penalty................................................................................................... 8 Regarding Political Prisoners...................................................................................................8 Regarding Freedom of Expression ........................................................................................ 8 Regarding Freedom of Association........................................................................................ 9 Regarding Torture..................................................................................................................... 9 Regarding the Draft Penal Code............................................................................................. 9 Regarding the Committee to Investigate the 1996 Deaths in Abu Salim Prison............ 9 Regarding International Human Rights Treaties ...............................................................10 -

The Tide Turns

November 2011 Anthony Bell, Spencer Butts, and David Witter THE LIBYAN REVOLUTION THE TIDE TURNS PART 4 Photo Credit: Fighters for Libya’s interim government rejoice after winning control of the Qaddafi stronghold of Bani Walid, via Wikimedia Commons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2011 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2011 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Anthony Bell, Spencer Butts, and David Witter THE LIBYAN REVOLUTION THE TIDE TURNS PART 4 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Anthony Bell is a Research Assistant at ISW, where he conducts research on political and security dynamics on Libya. He has previously studied the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, and published the ISW report Reversing the Northeastern Insurgency. Anthony holds a bachelor’s degree from the George Washington University in International Affairs with a concentration in Conflict and Security. He graduated magna cum laude and received special honors for his senior thesis on the history of U.S. policy towards Afghanistan. He is currently a graduate student in the Security Studies Program at Georgetown University. Spencer Butts is a Research Assistant for the Libya Project at ISW. Prior to joining ISW, Mr. Butts interned at the Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute at the Army War College where he wrote a literature review of the Commander’s Emergency Response Program in Iraq. -

Justice and the Rule Of

LIBYA AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL SUBMISSION FOR THE UN UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW 22ND SESSION OF THE UPR WORKING GROUP, MAY 2014 FOLLOW UP TO THE PREVIOUS REVIEW In its first Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in 2010, Libya accepted 66 recommendations, rejected 24 and gave no clear position on a further 30 recommendations.1 Following the 2011 armed conflict that toppled the rule of Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi, Libya formed a committee to revise its previous positions. In a welcome step, Libya accepted a further 47 recommendations in 2012.2 However, despite their public commitment, successive governments since 2011 have failed to ensure accountability for human rights abuses, which are perpetrated by the state, state-affiliated militias and armed groups at an alarming scale. Libya accepted in principle a recommendation to commute all existing death sentences and establish a moratorium on the use of the death penalty as a first step towards its abolition, but to date has not done so. 3 Regrettably, Libya has refused to “amend or repeal legislation that applies the death penalty to non-serious crimes”.4 It continues to be prescribed for a wide range of offences, including those related to the peaceful exercise of the rights to freedom of expression and association. Amnesty International welcomes Libya’s commitment to bring the security forces under legal oversight in compliance with international human rights standards.5 However, since 2011, the authorities have not been able to disband militias that have operated with little state oversight and perpetrated serious human rights abuses with impunity. 6 Libya also accepted recommendations to repeal laws that criminalize the peaceful exercise of the rights to freedom of expression, assembly and association.7 However, since 2011, the authorities have prosecuted and detained individuals for peacefully expressing their views under existing legislation. -

Investigation by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Libya: Detailed Findings * **

A/HRC/31/CRP.3 Distr.: General 15 February 2016 English only Human Rights Council Thirty-first session Agenda items 2 and 10 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Technical assistance and capacity-building Investigation by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Libya: detailed findings * ** Summary The present document contains the detailed findings of the investigation by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) on Libya. The principal findings and recommendations of OHCHR are provided in document A/HRC/31/47. * Reproduced as received. ** The information contained in this present document should be read in conjunction with the report of the investigation of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Libya (A/HRC/31/47 ). A/HRC/31/CRP.3 Contents Page I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 A. Mandate ................................................................................................................................... 3 B. Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 3 C. Challenges and constraints ....................................................................................................... 5 D. Acknowledgements -

A/Hrc/31/Crp.3

A/HRC/31/CRP.3 Distr.: General 23 February 2016 English only Human Rights Council Thirty-first session Agenda items 2 and 10 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Technical assistance and capacity-building Investigation by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Libya: detailed findings* ** Summary The present document contains the detailed findings of the investigation by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) on Libya. The principal findings and recommendations of OHCHR are provided in document A/HRC/31/47. * Reproduced as received. ** The information contained in this present document should be read in conjunction with the report of the investigation of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Libya (A/HRC/31/47). GE.16-02797(E) *1602797* A/HRC/31/CRP.3 Contents Page I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 A. Mandate ................................................................................................................................... 3 B. Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 3 C. Challenges and constraints ...................................................................................................... -

Just War Tradition and NATO's Libya Campaign: Western Imperialism Or the Moral High Ground?

JUST WAR TRADITION AND NATO’S LIBYA CAMPAIGN: WESTERN IMPERIALISM OR THE MORAL HIGH GROUND? Major A.S. Wedgwood JCSP 38 PCEMI 38 Master of Defence Studies Maîtrise en études de la défense Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and do Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs et not represent Department of National Defence or ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Ministère de Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used la Défense nationale ou des Forces canadiennes. Ce without written permission. papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par le Minister of National Defence, 2012 ministre de la Défense nationale, 2012. 1 2 CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE JCSP 38 Masters of Defense Studies - Thesis JUST WAR TRADITION AND NATO’S LIBYA CAMPAIGN: WESTERN IMPERIALISM OR THE MORAL HIGH GROUND? By Maj A.S. Wedgwood This paper was written by a student attending the Canadian Forces College in fulfilment of one of the requirements of the Course of Studies. The paper is a scholastic document, and thus contains facts and opinions, which the author alone considered appropriate and correct for the subject. It does not necessarily reflect the policy or the opinion of any agency, including the Government of Canada and the Canadian Department of National Defence. This paper may not be released, quoted or copied, except with the express permission of the Canadian Department of National Defence. Word Count: 19759 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my wife Katy for all of her support throughout this process, particularly for her tireless proofreading and deciphering of the Chicago Manual of Style. -

Layout Copy 1

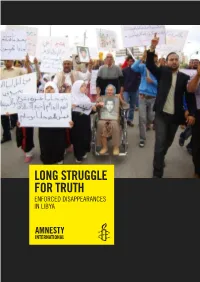

LONG STRUGGLE FOR TRUTH ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCES IN LIBYA 2 LONG STRUGGLE FOR TRUTH ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCES IN LIBYA ‘Libya today is not Libya of yesterday, and Libya of tomorrow, God willing, will be even better’ Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi, son of the Libyan leader and head of the Gaddafi International Charity and Development Foundation, March 2010 Thousands of Libyan families are waiting for isolation. Today it is a full member of the violations committed and to apologize. answers from the Libyan authorities. They international community, elected to the UN They want accountability and assurances all have relatives who have been forcibly Human Rights Council in May 2010. Sadly, that such abuses will not be repeated. disappeared or who have been killed by the country’s international reintegration has Only then will they be able to mourn and agents of the state in past decades. Despite not been accompanied by steps to address heal, and only then will the authorities be Libya’s recent transformation from pariah the legacy of gross human rights violations able to regain their trust. state to international player, they have had committed in past decades. no satisfactory responses to their demands Far from responding to the families’ for truth and justice. Routine abuses committed in the 1970s, legitimate demands, the Libyan authorities 1980s and 1990s included arbitrary have first ignored the families and later tried Only a few years ago, Libya was a closed detentions, enforced disappearances, torture to pacify them through offering financial country under UN, European Union and and other ill-treatment, extrajudicial compensation – accepted by some families US sanctions.