Weijmar Schultz, Willibrordus Canisius Maria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curative Pelvic Exenteration for Recurrent Cervical Carcinoma in the Era of Concurrent Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect EJSO xx (2015) 1e11 www.ejso.com Review Curative pelvic exenteration for recurrent cervical carcinoma in the era of concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy. A systematic review H. Sardain a,b, V. Lavoue a,b,c,*, M. Redpath d, N. Bertheuil b,e, F. Foucher a,J.Lev^eque a,b,c a CHU de Rennes, Gynecology Department, Tertiary Surgery Center, Teaching Hospital of Rennes, Hopital^ Sud, 16, Bd de Bulgarie, 35000 Rennes, France b Universite de Rennes, Faculty of Medicine, 2 Henry Guilloux, 35000 Rennes, France c INSERM, ER440, Oncogenesis, Stress and Signaling (OSS), Rennes, France d McGill University, Department of Pathology, Jewish General Hospital, Cote^ Sainte Catherine, Montreal, QC, Canada e CHU de Rennes, Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Tertiary Surgery Center, Teaching Hospital of Rennes, Hopital^ Sud, 16, Bd de Bulgarie, 35000 Rennes, France Accepted 26 March 2015 Available online --- Abstract Objective: Pelvic exenteration requires complete resection of the tumor with negative margins to be considered a curative surgery. The pur- pose of this review is to assess the optimal preoperative evaluation and surgical approach in patients with recurrent cervical cancer to in- crease the chances of achieving a curative surgery with decreased morbidity and mortality in the era of concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Methods: Review of English publications pertaining to cervical cancer within the last 25 years were included using PubMed and Cochrane Library searches. Results: Modern imaging (MRI and PET-CT) does not accurately identify local extension of microscopic disease and is inadequate for pre- operative planning of extent of resection. -

Pelvic Exenteration for the Management of Pelvic Malignancies

Chapter 7 Pelvic Exenteration for the Management of Pelvic Malignancies Daniel Paramythiotis, Konstantinia Kofina and Antonios Michalopoulos Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/61083 Abstract Pelvic exenteration is a surgical procedure first described by Brunschwig in 1948 as a curative or palliative treatment for pelvic and perineal tumors. It is actually a radical operation, involving en bloc resection of pelvic organs, including reproductive structures, bladder, and rectosigmoid. In patients with recurrent cervical and vaginal malignancy, it is associated with a 5-year survival of more than 50%. In spite of advances in surgical management, consequences such as stomas, are still frequently unavoidable for radical tumor excision. Most candidates for this procedure have been diagnosed with recurrent cervical cancer that has previously been treated with surgery and radiation, or radiation alone. Complications of pelvic exenteration are more severe than those of standard resection of a colorectal carcinoma, so it is not commonly performed, including wound infection, wound dehiscence (also described as burst abdomen) the creation of fistulae (perineal-fecal, uretero-vaginal, between conduit and perineal wound), urinary tract infections, perineal hernias and intestinal obstruction. Patients need to be carefully selected and counseled about risks and long-term issues related to the surgery. A comprehensive evaluation is required in order to exclude unresectable or metastatic disease. Evolution of the technique through laparoscopy and minimally invasive surgery may result in a reduction of morbidity and mortality. Keywords: Pelvic exenteration, gynecologic cancer 1. Introduction Pelvic exenteration was first described by Brunschwig and his colleagues of New York’s Memorial Hospital in 1948 [1] and was initially performed as a palliative surgical intervention © 2015 The Author(s). -

Treating Cervical Cancer If You've Been Diagnosed with Cervical Cancer, Your Cancer Care Team Will Talk with You About Treatment Options

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Treating Cervical Cancer If you've been diagnosed with cervical cancer, your cancer care team will talk with you about treatment options. In choosing your treatment plan, you and your cancer care team will also take into account your age, your overall health, and your personal preferences. How is cervical cancer treated? Common types of treatments for cervical cancer include: ● Surgery for Cervical Cancer ● Radiation Therapy for Cervical Cancer ● Chemotherapy for Cervical Cancer ● Targeted Therapy for Cervical Cancer ● Immunotherapy for Cervical Cancer Common treatment approaches Depending on the type and stage of your cancer, you may need more than one type of treatment. For the earliest stages of cervical cancer, either surgery or radiation combined with chemo may be used. For later stages, radiation combined with chemo is usually the main treatment. Chemo (by itself) is often used to treat advanced cervical cancer. ● Treatment Options for Cervical Cancer, by Stage Who treats cervical cancer? Doctors on your cancer treatment team may include: 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 ● A gynecologist: a doctor who treats diseases of the female reproductive system ● A gynecologic oncologist: a doctor who specializes in cancers of the female reproductive system who can perform surgery and prescribe chemotherapy and other medicines ● A radiation oncologist: a doctor who uses radiation to treat cancer ● A medical oncologist: a doctor who uses chemotherapy and other medicines to treat cancer Many other specialists may be involved in your care as well, including nurse practitioners, nurses, psychologists, social workers, rehabilitation specialists, and other health professionals. -

Once in a Lifetime Procedures Code List 2019 Effective: 11/14/2010

Policy Name: Once in a Lifetime Procedures Once in a Lifetime Procedures Code List 2019 Effective: 11/14/2010 Family Rhinectomy Code Description 30160 Rhinectomy; total Family Laryngectomy Code Description 31360 Laryngectomy; total, without radical neck dissection 31365 Laryngectomy; total, with radical neck dissection Family Pneumonectomy Code Description 32440 Removal of lung, pneumonectomy; Removal of lung, pneumonectomy; with resection of segment of trachea followed by 32442 broncho-tracheal anastomosis (sleeve pneumonectomy) 32445 Removal of lung, pneumonectomy; extrapleural Family Splenectomy Code Description 38100 Splenectomy; total (separate procedure) Splenectomy; total, en bloc for extensive disease, in conjunction with other procedure (List 38102 in addition to code for primary procedure) Family Glossectomy Code Description Glossectomy; complete or total, with or without tracheostomy, without radical neck 41140 dissection Glossectomy; complete or total, with or without tracheostomy, with unilateral radical neck 41145 dissection Family Uvulectomy Code Description 42140 Uvulectomy, excision of uvula Family Gastrectomy Code Description 43620 Gastrectomy, total; with esophagoenterostomy 43621 Gastrectomy, total; with Roux-en-Y reconstruction 43622 Gastrectomy, total; with formation of intestinal pouch, any type Family Colectomy Code Description 44150 Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with ileostomy or ileoproctostomy 44151 Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with continent ileostomy 44155 Colectomy, -

Pelvic Exenteration As Ultimate Ratio for Gynecologic Cancers: Single‑Center Analyses of 37 Cases

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2019) 300:161–168 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-019-05154-4 GYNECOLOGIC ONCOLOGY Pelvic exenteration as ultimate ratio for gynecologic cancers: single‑center analyses of 37 cases N. de Gregorio1 · A. de Gregorio1 · F. Ebner2 · T. W. P. Friedl1 · J. Huober1 · R. Hefty3 · M. Wittau4 · W. Janni1 · P. Widschwendter1 Received: 5 February 2019 / Accepted: 5 April 2019 / Published online: 22 April 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Background Pelvic exenterations are a last resort procedure for advanced gynecologic malignancies with elevated risks in terms of patients’ morbidity. Methods This single-center analysis reports surgical details, outcome and survival of all patients treated with exenteration for non-ovarian gynecologic malignancies at our university hospital during a 13-year time period. We collected data regarding patients and tumor characteristics, surgical procedures, peri- and postoperative management, transfusions, complications, and analyzed the impact on survival outcomes. Results We identifed 37 patients between 2005 and 2013 with primary or relapsed cervical cancer (59.5%), vulvar cancer (24.3%) or endometrial cancer (16.2%). Median age was 60 years and most patients (73%) had squamous cell carcinomas. Median progression-free survival was 26.2 months and median overall survival was 49.9 months. The 5-year survival rates were 34.4% for progression-free survival and 46.4% for overall survival. There were no signifcant diferences in progres- sion-free survival and overall survival with regard to disease entity. Patients with tumor at the resection margins (R1) had a nearly signifcantly worse progression-free survival (median: 28.5 vs. -

Seer Program Code Manual

THE SEER PROGRAM CODE MANUAL Revised Edition June 1992 CANCER STATISTICS BRANCH SURVEILLANCE PROGRAM DIVISION OF CANCER PREVENTION AND CONTROL NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH Effective Date: Cases Diagnosed January 1, 1992 The SEER Program Code Manual Revised Edition June 1992 Editors Jack Cunningham Lynn Ries Benjamin Hankey Jennifer Seiffert Barbara Lyles Evelyn Shambaugh Constance Percy Valerie Van Holten Acknowledgements The editors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Terry Swenson, Maureen Troublefield, Diane Licitra, and Jerome Felix of Information Management Services, Inc., in the preparation of the SEER Program Code Manual. The editors also wish to acknowledge the assistance of Dr. John Berg in preparation of the section on multiple primary determination for lymphatic and hematopoietic diseases. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE TO THE REVISED EDITION ....................................... vii COMPUTER RECORD FORMAT ............................................ 1 INTRODUCTION AND GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS .............................. 5 REFERENCES .......................................................... 37 SEER CODE SUMMARY .................................................. 39 I BASIC RECORD IDENTIFICATION ...................................... 57 1.01 SEER Participant ........................................... 58 1.02 Case Number .............................................. 59 1.03 Record Number ............................................ 60 -

Primary Pelvic Exenteration: Our Experience with 23 Patients from a Single Institution

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 22: 1060, 2021 Primary pelvic exenteration: Our experience with 23 patients from a single institution MIHAI GHEORGHE1, ALEXANDRA LAVINIA COZLEA1, SZILARD LEO KISS1, MIHAI STANCA1, MIHAI EMIL CĂPÎLNA1, NICOLAE BACALBAȘA2 and ANDREEA ANAMARIA MOLDOVAN3 1First Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic, ‘George Emil Palade’ University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science and Technology, 540136 Târgu Mureș; 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, ‘Carol Davila’ University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 020022 Bucharest; 3Department of Infectious Diseases, Brașov County Emergency Hospital, 500326 Brașov, Romania Received May 24, 2021; Accepted June 23, 2021 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2021.10494 Abstract. This study was designed with an aim to share our Introduction experience of primary pelvic exenterations. The study included 23 patients with different types of pelvic cancer enrolled at a In patients with advanced primary or recurrent gyneco‑ single institution between November 2011 and July 2020. The logic (1), urologic or rectal cancers without metastatic disease, patient mean age was 55 years (range, 43‑72 years) and the extensive aggressive surgery such as pelvic exenteration may oncological indications included: Stage IVa cervical cancer be necessary for curative intent treatment (2). (11 cases, 48.9%), stage IVa endometrial cancer (1 case, 4.3%), Brunschwig was the first to describe pelvic exentera‑ stage IVa vaginal cancer (6 cases, 26%), stage IIIb bladder tion in the 1940s (3). Exenteration was initially considered cancer (3 cases, 13%), stage IIIc rectal cancer (1 case, 4.3%) as a palliative procedure for patients with extensive pelvic and undifferentiated pelvic sarcoma (1 case, 4.3%). Total, cancers, with an extremely high perioperative mortality rate anterior, and posterior pelvic exenterations were performed of 23%. -

Introduction to Pelvic Obstetric and Gynaecology Physiotherapy

INTRODUCTION TO PELVIC OBSTETRIC AND GYNAECOLOGY PHYSIOTHERAPY An Educational Resource Published by the Pelvic, Obstetric and Gynaecology Physiotherapy Contact: POGP Administration, Fitwise Management Ltd., Drumcross Hall, Bathgate, West Lothian EH48 4JT T: 01506 811077 E: [email protected] or visit the POGP website www.pogp.org.uk for further information. ©POGP 2015 for review 2018 Contents CCCCC Introduction .........................................................................................................3 Core skill framework.............................................................................................4 Obstetrics..............................................................................................................5 Urology, Gynaecology and Colorectal..................................................................8 Breast Oncology……………………………………………………..………...………………..….……..17 Appendices 1. Obstetric abbreviations ..........................................................................19 2. Obstetric terminology ............................................................................20 3. Urology/ Gynaecology terminology……………………………………..……………..26 4. Gynaecology surgery terminology…………………………………………..………....29 5. Colorectal terminology…………………………………………………..………………..…31 6. Advanced clinical objectives for performing internal examinations…….34 C o n t e n t s 1 T H R E Introduction It is acknowledged that physiotherapists may become involved in the management of pelvic, obstetric and gynaecology patients -

OBGYN Outpatient Surgery Coding

OBGYN Outpatient Surgery Coding Anatomy Anatomy • Hyster/o – uterus, womb • Uter/o – uterus, womb • Metr/o – uterus, womb • Salping/o – tube, usually fallopian tube • Oophor/o – ovary • Ovari/o - ovary Terminology • Colpo – vagina • Cervic/o – cervix, lower part of the uterus, the “neck” • Episi/o – vulva • Vulv/o – vulva • Perine/o – the space between the anus and vulva Hysterectomy • A hysterectomy is an operation to remove a woman's uterus. • A woman may have a hysterectomy for different reasons, including: • Uterine fibroids that cause pain • bleeding, or other problems. • Uterine prolapse, which is a sliding of the uterus from its normal position into the vaginal canal. Hysterectomy • There are around 30 hysterectomy CPT codes. • To find the correct code you have to first check: • the surgical approach and • extent of the procedure. Surgical Approaches • Abdominal – the uterus is removed via an incision in the lower abdomen • Vaginal – the uterus is removed via an incision in the vagina • Laparoscopic – the procedure is performed using a laparoscope , inserted via several small incisions in the body. • Their are also CPT codes for laparoscopic-assisted vaginal approach. In this procedure ,the scope is inserted via a small incisions in the vagina. Extent of Procedure • Total hysterectomy: It includes laparoscopically detaching the entire uterine cervix and body from the surrounding supporting structures and suturing the vaginal cuff. It includes bivalving, coring, or morcellating the excised tissues, as required. The uterus is then removed through the vagina or abdomen. • Subtotal, partial or supracervical hysterectomy: It is the removal of the fundus or op portion of the uterus only, leaving the cervix in place. -

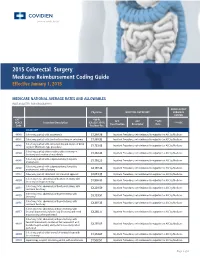

2015 Colorectal Surgery Medicare Reimbursement Coding Guide Effective January 1, 2015

2015 Colorectal Surgery Medicare Reimbursement Coding Guide Effective January 1, 2015 MEDICARE NATIONAL AVERAGE RATES AND ALLOWABLES (NOT ADJUSTED FOR GEOGRAPHY) AMBULATORY Physician HOSPITAL OUPATIENT SURGICAL CENTER CPT™* *MPFS APC APC **APC HCPCS Procedure Description (CF=$35.7547) ***ASC Classification Descriptor Rate Code Fac/Non-Fac COLECTOMY 44140 Colectomy, partial; with anastomosis $1,388.36 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare 44141 Colectomy, partial; with skin level cecostomy or colostomy $1,888.92 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare Colectomy, partial; with end colostomy and closure of distal 44143 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare segment (Hartmann type procedure) $1,723.02 Colectomy, partial; with resection, with colostomy or 44144 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare ileostomy and creation of mucofistula $1,832.43 Colectomy, partial; with coloproctostomy (low pelvic 44145 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare anastomosis) $1,716.23 Colectomy, partial; with coloproctostomy (low pelvic 44146 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare anastomosis), with colostomy $2,197.84 44147 Colectomy, partial; abdominal and transanal approach $2,013.35 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with 44150 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare -

New Insights from One Case of Female Ejaculationjsm 2472 3500..3504

3500 CASE REPORTS New Insights from One Case of Female Ejaculationjsm_2472 3500..3504 Alberto Rubio-Casillas, Biologist* and Emmanuele A. Jannini, MD† *Escuela Preparatoria Regional de Autlán, Biology Laboratory, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, México; †Course of Endocrinology and Sexology, Department of Experimental Medicine, University of L’Aquila, Rome, Italy DOI: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02472.x ABSTRACT Introduction. Although there are historical records showing its existence for over 2,000 years, the so-called female ejaculation is still a controversial phenomenon. A shared paradigm has been created that includes any fluid expulsion during sexual activities with the name of “female ejaculation.” Aim. Todemonstrate that the “real” female ejaculation and the “squirting or gushing” are two different phenomena. Methods. Biochemical studies on female fluids expelled during orgasm. Results. In this case report, we provided new biochemical evidences demonstrating that the clear and abundant fluid that is ejected in gushes (squirting) is different from the real female ejaculation. While the first has the features of diluted urines (density: 1,001.67 Ϯ 2.89; urea: 417.0 Ϯ 42.88 mg/dL; creatinine: 21.37 Ϯ 4.16 mg/dL; uric acid: 10.37 Ϯ 1.48 mg/dL), the second is biochemically comparable to some components of male semen (prostate-specific antigen: 3.99 Ϯ 0.60 ¥ 103 ng/mL). Conclusions. Female ejaculation and squirting/gushing are two different phenomena. The organs and the mecha- nisms that produce them are bona fide different. The real female ejaculation is the release of a very scanty, thick, and whitish fluid from the female prostate, while the squirting is the expulsion of a diluted fluid from the urinary bladder. -

And Sexual Behaviour of Local X Orgasm (Female)

SINGAPORE MEDICAL JOURNAL SOME ASPECTS OF SEXUAL KNOWLEDGE AND SEXUAL BEHAVIOUR OF LOCAL WOMEN - RESULTS OF A SURVEY: X ORGASM (FEMALE) V Atputharajah SYNOPSIS 1012 sexually active females were interviewed regarding their sexual practices. 85 of 94 (90.4 percent) of those who masturbated reached orgasm while 5.3 percent did not. 63.5 percent of those who did reach orgasm by masturbation, thought that orgasm at intercourse felt better than that at mastur- bation. 15.3 percent felt that orgasm felt the same with either activity. 12.1 percent of the total sample (11.0 percent of married women and 20.7 percent of unmarried women) did not get orgasm at inter- course. 13.0 percent (13.3 percent of married women and 11.3 percent of unmarried women) orgasmed at every coital experience. 91 percent (91.9 percent of married women and 84.9 percent of unmarried women) said they enjoyed intercourse. Orgasm, its nature, onset and role and its significance and technique to achieve it are discussed. INTRODUCTION Orgasm is described as the ultimate and most fantastic sensa- tion ever experienced and is a cortical sensory experience. It is limited to a few seconds of physical release and is the acme of pleasure for most people. During the few seconds the vasocon- gestion and myotonia from Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology developed sexual stimulation is Alexandra Hospital released. This release gives a great renewal of all the senses and Alexandra Road a complete relief of boredom (1,2,3). Singapore 0314 The female orgasm appears to be more vulnerable to inhibition than does the male's.