MAKING the SHINING Or How Kubrick Copied a Single Picture Into the Viewer’S Mind by Using the TV Mosaic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Kubrick's Kelley O'brien University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2018 "He Didn't Mean It": What Kubrick's Kelley O'Brien University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation O'Brien, Kelley, ""He Didn't Mean It": What Kubrick's" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7204 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “He Didn‟t Mean It”: What Kubrick‟s The Shining Can Teach Us About Domestic Violence by Kelley O‟Brien A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts With a concentration in Humanities Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Maria Cizmic, Ph.D. Amy Rust Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2018 Keywords: Patriarchy, Feminism, Gender Politics, Horror, American 1970s Copyright © 2018, Kelley O‟Brien Dedication I dedicate this thesis project to my mother, Terri O‟Brien. Thank you for always supporting my dreams and for your years of advocacy in the fight to end violence against women. I could not have done this without you. Acknowledgments First I‟d like to express my gratitude to my thesis advisor Dr. -

Kubrick Sur Internet Philippe Mather

Document generated on 09/27/2021 9:48 p.m. Ciné-Bulles Le cinéma d’auteur avant tout Kubrick sur Internet Philippe Mather Volume 18, Number 4, Summer 2000 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/33604ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec ISSN 0820-8921 (print) 1923-3221 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Mather, P. (2000). Kubrick sur Internet. Ciné-Bulles, 18(4), 40–45. Tous droits réservés © Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec, 2000 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ sur Internet Kubrick sur Internet PAR PHILIPPE MATHER siècle, mais il devient utile de faire contiennent des documents et des un bilan provisoire en examinant liens hypertextes intéressants, parmi les ressources dans Internet concer lesquels on comptera (l'incontour our certains, le récent Eyes nant les films du réalisateur anglo- nable) Internet Movie Database, Wide Shut serait un film américain. dont nous avons souvent eu Pprétentieux et misogyne. Selon l'occasion de souligner les qualités, Martin Scorsese, il s'agit de l'un des Premier constat: il existe de nom et qui sert également de référence meilleurs films des années 1990. -

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, the SHINING (1980, 146 Min)

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, THE SHINING (1980, 146 min) Directed by Jules Dassin Directed by Stanley Kubrick Based on the novel by Stephen King Original Music by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind Cinematography by John Alcott Steadycam operator…Garrett Brown Jack Nicholson...Jack Torrance Shelley Duvall...Wendy Torrance Danny Lloyd...Danny Torrance Scatman Crothers...Dick Hallorann Barry Nelson...Stuart Ullman Joe Turkel...Lloyd the Bartender Lia Beldam…young woman in bath Billie Gibson…old woman in bath Anne Jackson…doctor STANLEY KUBRICK (26 July 1928, New York City, New York, USA—7 March 1999, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England, UK, natural causes) directed 16, wrote 12, produced 11 and shot 5 films: Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Full Metal Jacket (1987), The Shining Lyndon (1976); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (1980), Barry Lyndon (1975), A Clockwork Orange (1971), 2001: A on Material from Another Medium- Full Metal Jacket (1988). Space Odyssey (1968), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Lolita (1962), Spartacus STEPHEN KING (21 September 1947, Portland, Maine) is a hugely (1960), Paths of Glory (1957), The Killing (1956), Killer's Kiss prolific writer of fiction. Some of his books are Salem's Lot (1974), (1955), The Seafarers (1953), Fear and Desire (1953), Day of the Black House (2001), Carrie (1974), Christine (1983), The Dark Fight (1951), Flying Padre: An RKO-Pathe Screenliner (1951). Half (1989), The Dark Tower (2003), Dark Tower: The Song of Won Oscar: Best Effects, Special Visual Effects- 2001: A Space Susannah (2003), The Dark Tower: The Drawing of the Three Odyssey (1969); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (2003), The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger (2003), The Dark Tower: on Material from Another Medium- Dr. -

Stanley Kubrick: a Biography Free

FREE STANLEY KUBRICK: A BIOGRAPHY PDF Vincent Anthony Lobrutto | 606 pages | 06 May 1999 | The Perseus Books Group | 9780306809064 | English | Cambridge, MA, United States Stanley Kubrick - Wikipedia His family were Jewish immigrants from Austria, Romania, and Russia. Stanley was considered intelligent, despite poor grades at school. Hoping that a change of scenery would produce better academic performance, Kubrick's father sent him in to Pasadena, California, to stay with his uncle, Martin Perveler. Returning to the Stanley Kubrick: A Biography in for his last year of grammar school, there seemed to be little change in his attitude or his results. Hoping to find something to interest his son, Jack introduced Stanley to chess, with the desired result. Kubrick took to the game passionately, and quickly became a skilled player. Chess would become an Stanley Kubrick: A Biography device for Kubrick in later years, often as a tool for dealing with recalcitrant actors, but also as an artistic motif in his films. Jack Kubrick's decision to give his son a camera for his thirteenth birthday would be an even wiser move: Kubrick became an avid photographer, and would often make trips around New York taking photographs which he would develop in a friend's darkroom. After selling an unsolicited photograph to Look Magazine, Kubrick began to associate with their staff photographers, and at the age of seventeen was offered a job as an apprentice photographer. In the next few Stanley Kubrick: A Biography, Kubrick had regular assignments for "Look", and would become a voracious movie-goer. Together with friend Alexander SingerKubrick planned a move into film, and in sank his savings into making the documentary Day of the Fight This was followed by several short commissioned documentaries Flying Padreand The Seafarersbut by attracting investors and hustling chess games in Central Park, Kubrick was able to make Fear and Desire in California. -

The Shining: a Comparative Analysis of the Original Novel and Its Adaptation

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jan Zbořil The Shining: A Comparative Analysis of the Original Novel and its Adaptation Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr. 2013 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………… 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Tomáš Pospíšil, for his patience and understanding. I would also like to thank my friend Jakub Hamari, who provided incredible support during all phases of my work. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction...............................................................................................5 2. The Authors 2.1 Stephen King.................................................................................7 2.2 Stanley Kubrick.............................................................................9 3. The Book 3.1 Origin..........................................................................................14 3.2 Form............................................................................................15 3.3 The Narrative...............................................................................16 3.4 Critical Analysis..........................................................................20 3.5 Characters....................................................................................23 4. The Movie 4.1 Origin..........................................................................................32 -

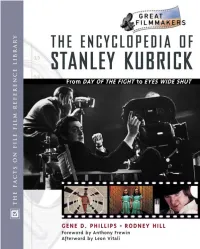

The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK GENE D. PHILLIPS RODNEY HILL with John C.Tibbetts James M.Welsh Series Editors Foreword by Anthony Frewin Afterword by Leon Vitali The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick Copyright © 2002 by Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hill, Rodney, 1965– The encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick / Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill; foreword by Anthony Frewin p. cm.— (Library of great filmmakers) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4388-4 (alk. paper) 1. Kubrick, Stanley—Encyclopedias. I. Phillips, Gene D. II.Title. III. Series. PN1998.3.K83 H55 2002 791.43'0233'092—dc21 [B] 2001040402 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K.Arroyo Cover design by Nora Wertz Illustrations by John C.Tibbetts Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Stanley Kubrick As Auteur and Adapter University of Sydney

Grant Domonic Malfitano [REDACTION] The Duality of Man: Stanley Kubrick as Auteur and Adapter University of Sydney Faculty of Arts, Department of English Thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Master of Research 1 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. I certify that the intellectual content of this this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. 2 Dedication For my parents, who lit the flame. 3 List of Contents Title Page 1 Statement of Originality 2 Dedication 3 Abstract 5 Introduction - Adaptation and Adaptation Theory; 6 i) Fidelity 10 ii) Intertextuality 11 iii) Raw Material Adaptation 14 iv) The place of the auteur in adaptation studies 16 The Kubrickian Tenets of Adaptation Chapter 1 – Narrative and Structure. 18 Chapter 2 – Visual Technique 35 Chapter 3 – Actor Performance 60 Chapter 4 – Music Selection, Arrangement and Design 85 In Conclusion 103 4 Abstract In this thesis I examine the scholarship of Adaptation Theory, commencing with the seminal work of George Bluestone in 1957, up to and including the more recent approaches of Kyle Meikle (2013), Thomas Leitch (2007), Linda Hutcheon (2006) and both Brian McFarlane (1996) and Karen Kline (1996). Each of these theorists has grappled with the overarching concept of fidelity, the status of film as autonomous art, the status of film authorship, and textual primacy. Secondly, I apply the current scholarship on Adaptation Theory to the work of film auteur, Stanley Kubrick. -

Collaborative Authorship in Stanley Kubrick's Films

Voices and noises: Collaborative authorship in Stanley Kubrick’s films Manca Perko Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies January 2019 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis sets out to challenge the mythology surrounding Kubrick’s filmmaking practice. The still dominant auteur approach in Kubrick studies identifies the director’s filmmaking practice as autonomous, with little creative input from his crew members. Following the recent shift in research that focuses on the collaborative nature of Kubrick’s working practice, I argue for a different perspective on creative practice in film production. The working process in Kubrick’s crews is shown to exhibit strong collaborative features and to encourage individual creative input. This thesis is based on the examination of historical evidence acquired from the Stanley Kubrick Archive in London and an extensive collection of mediated and personally conducted interviews with Kubrick’s collaborators. The historical discourse analysis employed in this thesis is rooted in New Film History methodologies and, with its findings, leads to an alternative perspective on film history. The challenge to the accepted view (or myth) of Kubrick is achieved with the use of discourse sources from production and from the archive, presented in the form of stories from pre-production to the promotion stage of film production. -

Kubrick: a True Artist. an Interview with Christiane Kubrick and Jan Harlan

KUBRICK: A TRUE ARTIST. AN INTERVIEW WITH CHRISTIANE KUBRICK AND JAN HARLAN Artur Piskorz Ph. D. Pedagogical University in Krakow, Poland English Department ABSTRACT In May 2014 an exhibition opened in the National Musem in Krakow, Poland, devoted to one of the greatest filmmakers – Stanley Kubrick. Christiane, Kubrick’s wife, and her brother, Jan Harlan, himself a long time collaborator of Kubrick’s, have selected a few hundred items related to individual films and put them on display, so providing a once in a lifetime experience for anybody wanting to immerse themselves in the Kubrickian universe. In the interview, Christiane Kubrick and Jan Harlan discuss the idea behind the exhibition as well as their life and work with the late great director. Key words: Kubrick, exhibition, Krakow, Christiane, Harlan, interview. RESUMEN «Kubrick: un verdadero artista. Entrevista con Christiane Kubrick y Jan Harlan». El Museo Nacional de Cracovia inauguró en mayo de 2014 una exposición sobre Stanley Kubrick, que supuso una oportunidad única para el visitante interesado en el universo del director. En ella se exhiben varios cientos de objetos y referencias coleccionados por su viuda, Christiane, 109 y el hermano de ésta, Jan Harlan, quien a su vez fue un estrecho colaborador suyo. En la entrevista que sigue, ambos comentan la idea que dio origen a la exposición, así como sus experiencias personales y profesionales con el gran cineasta fallecido. Palabras clave: Kubrick, exposición, Cracovia, Christiane, Harlan, entrevista. The untimely death of Stanley Kubrick 15 years ago was a terrible blow to anybody interested in cinema. A mythical figure, a passionate moralist, a visionary filmmaker whose films redefined film art – it would be quite easy to compile a lengthy list of similar descriptions. -

Stanley Kubrick: Producers and Production Companies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by De Montfort University Open Research Archive Stanley Kubrick: Producers and Production Companies Thesis submitted by James Fenwick In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University, September 2017 1 Abstract This doctoral thesis examines filmmaker Stanley Kubrick’s role as a producer and the impact of the industrial contexts upon the role and his independent production companies. The thesis represents a significant intervention into the understanding of the much-misunderstood role of the producer by exploring how business, management, working relationships and financial contexts influenced Kubrick’s methods as a producer. The thesis also shows how Kubrick contributed to the transformation of industrial practices and the role of the producer in Hollywood, particularly in areas of legal authority, promotion and publicity, and distribution. The thesis also assesses the influence and impact of Kubrick’s methods of producing and the structure of his production companies in the shaping of his own reputation and brand of cinema. The thesis takes a case study approach across four distinct phases of Kubrick’s career. The first is Kubrick’s early years as an independent filmmaker, in which he made two privately funded feature films (1951-1955). The second will be an exploration of the Harris-Kubrick Pictures Corporation and its affiliation with Kirk Douglas’ Bryna Productions (1956-1962). Thirdly, the research will examine Kubrick’s formation of Hawk Films and Polaris Productions in the 1960s (1962-1968), with a deep focus on the latter and the vital role of vice-president of the company. -

Stanley Kubrick: Full Metal Jacket 1987 116 Minutes

November 13, 2007 (XV:12) Stanley Kubrick: Full Metal Jacket 1987 116 minutes Produced and Directed by Stanley Kubrick Based on Gustav Hasford’s novel, The Short Timers Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr & Gustav Hasford Original Music by Vivian Kubrick (as Abigail Mead) Cinematography by Douglas Milsome Film Editing by Martin Hunter Matthew Modine..Pvt. Joker Adam Baldwin..Animal Mother Vincent D'Onofrio..Leonard 'Private Pyle' Pratt R. Lee Ermey..Gny. Sgt,Hartman Dorian Harewood..Eightball Kevyn Major Howard..Rafterman Arliss Howard..Pvt.Cowboy Ed O'Ross..Lt.Touchdown John Terry..Lt.Lockhart Kieron Jecchinis..Crazy Earl Kirk Taylor..Payback Tim Colceri..Doorgunner Jon Stafford..Doc Jay Bruce Boa..Poge Colonel Ian Tyler..Lt.Cleves Sal Lopez..T.H.E. Rock Gary Landon Mills..Donlon Papillon Soo..Da Nang Hooker Peter Edmund..Snowball Peter Merrill..TV Journalist Ngoc Le..VC Sniper Herbert Norville..Daytona Dave Leanne Hong..Motorbike Hooker Nguyen Hue Phong..Camera Thief Tan Hung Francione..ARVN Pimp Duc Hu Ta..Dead N.V.A. Marcus D'Amico..Hand Job Stanley Kubrick..Murphy (voice) Costas Dino Chimona..Chili Vivian Kubrick..News Camera Operator at Mass Grave Gil Kopel..Stork David Palffy..Mass Grave Soldier Keith Hodiak..Daddy D.A. John Ward..TV Camera Operator STANLEY KUBRICK (26 July 1928, New York, New York—7 March 1999, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England), generally regarded as one of the greatest directors, made only 13 feature films. He so loathed the first of these (Fear and Desire 1953) that he withdrew it from circulation. The others are: Killer’s Kiss 1955, The Killing 1956, Paths of Glory 1957, Spartacus 1960, Lolita 1962, Dr. -

Northumbria Research Link

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Egan, Kate (2015) Precious footage of the auteur at work: framing, accessing, using, and cultifying Vivian Kubrick's Making the Shining. New Review of Film and Television Studies, 13 (1). pp. 63-82. ISSN 1740-0309 Published by: UNSPECIFIED URL: This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://northumbria-test.eprints- hosting.org/id/eprint/54194/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/pol i cies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) Precious Footage of the Auteur at Work: Framing, Accessing, Using and Cultifying Vivian Kubrick’s Making The Shining Kate Egan, Aberystwyth University, UK Abstract This article aims to explore the centrality to Kubrick’s cult reputation of a touchstone resource for Kubrick fans: Vivian Kubrick’s 1980 documentary Making The Shining.