Commander Beverly Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stapleton Enterprise It’S Your Right to Know Mcpherson Co

SERVING LOGAN & McPHERSON COUNTIES THE STAPLETON FOR OVER 100 YEARS SinceLOGAN 1912 COUNTY, • creativeprintersonline.com STAPLETON NEBRASKA 69163 (USPS THURSDAY, 518780) NOVEMBER THURSDAY, 5, 2020 JANUARY 5, 2017 NO. NO. 1 45 Murder at Deadwood Solved COURTESY Murder at Deadwood characters, front row, l-r: Velda Cassell, bartender; Marcia Hora, saloon girl; Lori Streit, Henrietta High-Stakes; Shad Streit, Mitch Maverick; Rex Hanna, Marshal Dalton; and Cindy Frey, murder mystery coordinator. Middle row, l-r: Kendra Cutler, saloon girl; Connie O’Brien, Elizabeth Money; Klara Daly Minnie Money; Polly Burnside, Anna Belle; Amber Rooney, Sally Starr; Lauren Leetch, Taffy Garrette; Robin Garlett, Holly Hickok; Abby Sabel, Banker Bonnie; Jeana Hanna, Poker Alice; Candy Salisbury, Black Barbara; and Kourtney Cutler, saloon girl. Back row, l-r: Ash Ramirez, Banker Bob; Toby Kinderknecht, Montgomery Money; Rich Burnside, Harry High-Stakes; Kaman Dailey, Clay Coldwell; Art Leetch, Gambling Jack; Bryce Funk, Sheriff Sam; Tim Karn, Jesse Wales; and Scott Salisbury, Billy-The-Bartender. The Stapleton Commu- centered around the to be a very financially Leetch, gambler. Banker Bob - Ash Scott Salisbury, Saloon nity Center was trans- small western town of successful venture for the Anna Belle - Polly Burn- Ramirez, bank owner. bartender and book- formed into Deadwood Deadwood as people had saloon. side, wife of Gambling Banker Bonnie - Abby keeper. for the first annual poker been pouring into town As the evening unfolded Jack. Sabel, wife to Banker Bob. Overall coordinator - tournament, Saturday, for the biggest poker tour- Mitch Maverick (Shad Mitch Maverick - Shad Jesse Wales - Tim Karn, Cindy Frey. October 24. nament this side of the Streit) was murdered. -

E Lectionwrapup

PrebaN y every preaideat, with, per- tap», the exception of Franklin D. Roo IE sevelt, w ishes he could serve m erely as (weebformother ’s d a y I the president of the United Slates. But a* the embattled Mr. Reagw has beea taught, the U SA president m ist con sider him self the president of the world, whefcer he likes it sr aM. No matter what move he make* It la certain to r x l> irritate the aattoaals of some ether coaatry. Take the current trip abroad. If foreigner* read the newspapers or listened to the radio or watched T V they would think the coaatry had exported the most hideous character in the land — rather than one of the most popular an d SOl'TH-BKRGKN KKMKW presidents ever elected. VOL. S3 NO. 42 i at SI Ridge Rd.. Lyndtom. N J. THURSDAY, M AY », 1985 SrcawdCIaM PaaUge Paid , HaHwfart. NJ. I - , h.m Pahttaheft) ekly E lection w rapup Every four years Lyndhurst Thirteen candidates, plus a non that because of a somewhat lack ing has been between the two slates voters go to the polls to elect a five- binding referendum on the proposed lustre cam paign the turn-out will be 'Hiree of the candidates are running member Board of Commissioners. resource recovery plant, will face smaller if bad weather prevails. independently The election of 1965 falls on next the votes when they enter the polling However, if the day is sunny and Since Lyndhurst operates under Tuesday when the polls in the 15 booths. -

Remembering the 1983 LCU Baseball Championship 4

Remembering the 1983 LCU Baseball Championship 4 LCU Alumna Helps Those with Aphasia 16 How LCU Changed One Man's Life 24 Volume 54 • Issue 1 Winter 2014 LUBBOCK CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY from the president The LCU Difference Higher education finds itself under a microscope, subject to intense scrutiny about its continuing value. One recent book that offers a strong critique of higher education is entitled simply, “Is College Worth It?” The question of “value” is typically framed in simple economic terms. Do students obtain a sufficient return on investment from their college degree? The focus on economic return is understandable at a time when tuition costs continue to rise, most graduates leave college with some debt, and government support for higher education is in decline. Even so, viewed simply in Reflections is economic terms, a college degree continues to be a very published two good investment. Statistics reflect that a college graduate will earn substantially more times a year by over a lifetime than a person without a college degree. Indeed, a recent survey by Lubbock Christian payscale.com found a very strong “return on investment” from an LCU degree, one that University and exceeded that of many older, larger, and better-endowed institutions. produced by But the LCU Difference is about more than mere economic return. Don’t get me the Marketing wrong. During all of ourLUBBOCK fifty-six years CHRISTIANwe have worked to UNIVERSITYprepare students for life Communications after college, to graduate “career-ready” students. And, indeed, we do that very thing Department. extraordinarily well in every course of study we offer today. -

Atunited States

Dutch Speaker Realistically Looks At United States half the size of Lane Holland the American way sof life Boasting of the lowest illiter- A co only py Mary largest Dutch political group is Carolina, the Netherlands Editor through her 10,000 mile tour of - the Roman Catholic party. rate in the world, the South Managing numerous s eight years his 11 colléges and universities. When a person reaches the Netherlands “There are no general courses,” | agometimes Americans to the United States in Ping ‘of compulsory edacation, which voting age of 23, he is tined un- she said. “One tackles his special but not tion with the United Nations. is followed selective school- | now how to teach, less he votes in Dutch elections, ing in see secre tecretarial and field right away.” “You have 7-day be praised Ameri- shat to teach ; and the Dutch churches, for voting is considered to vocational school Said Miss Miss Hefting and we have one-day churches. “not only a right and a privi- “You (the United cans informality, hospitality, | gow what to teach, but not Everything Hefting, give happens on Sunday,” lege, but a requirement.” States) educate the inany a friendliness, and ability to ow to teach,” said Miss she said in her explanation of criticism, and con- Miss Hefting stated that the little, and we educate the few constructive the functions of religion in the with these | Jeantine Hefting in her com- Communists were not outlawed ‘a Jot.” cluded her lecture Netherlands. Dutch churches “We (the Dutch) have do in the Netherlands, but were al- words, jrigon of life in the United ‘ Institutions of higher educa- and disadvant- not provide social activities lowed to hold positions on the the advantages throughout the week as do tion are quite different from the a long history; you (the States with life in Holland. -

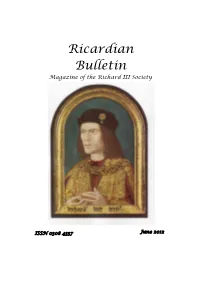

Ricardian Bulletin Is Produced by the Bulletin Editorial Committee, Printed by Micropress Printers Ltd

Ricardian Bulletin Magazine of the Richard III Society ISSN 0308 4337 June 2012 Ricardian Bulletin June 2012 Contents 2 From the Chairman 3 Society News and Notices Annual General Meeting 2012 New Faces on the Bulletin Committee Our Research Officer has gained her PhD Updates on our projects Fotheringhay Revisited Report on the Society’s Triennial Conference at Loughborough, by Ken Hillier 15 News and Reviews 22 In Prospect 24 Media Retrospective 26 The Man Himself: Looking for Richard: in Search of a King, by Philippa Langley 29 Yorkist Era Sports, by Compton Reeves 32 A Series of Remarkable Ladies. 1, Clarice Orsini, by Rita Diefenhardt-Schmitt 33 Dark Sovereign Resuscitates Richard III, by Robert Fripp 37 ‘Bambi’ versus ‘Superswine’, by Geoffrey Wheeler 40 Jane Austen’s opinion of Richard III ... and others 41 Spying out Bosworth battlefield? by Lesley Boatwright 42 That wasn’t his wife - that was an angel ... 43 Correspondence 46 The Barton Library 48 Future Society Events 51 From our Australasian Correspondent, by Dorothea Preis 54 Branch and Group Contacts 56 Branches and Groups 58 New Members and Recently Deceased Members 59 Obituaries 60 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. All contributions should be sent to Lesley Boatwright. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for March issue; 15 April for June issue; 15 July for September issue; 15 October for December issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. Bulletin & Ricardian Back Numbers Back issues of The Ricardian and the Bulletin are available from Judith Ridley. If you are interested in obtaining any back numbers, please contact Mrs Ridley to establish whether she holds the issue(s) in which you are interested. -

Human Effort 1Enchants' Production

Vol. 51, No. 4 • University High School, 1362 E. 59th St., Chicago, Ill. 60637 • Tues., Nov. 18, 1975 Photo by Jim Reginato Photo by David Cahnmann Photo by David Cahnmann THREE STAG E S in the production of thi s year' s which will compo se part of the setting. costume. fall play, "Th e E nchanted," are shown in thes e photo s, from left. REH EARSING A "BEAT," a production unit of REFERRING to her book of notes, Drama DAN HUTTENLOCHER, technical director the play, from left, Scott Wilkerson, Jon Simon, Hal T eacher Liucija Ambro sini, director of the play, (center), Andy Neal (ba ck to cam era) and Norman Bernst ein and Stephen Patter son work on lin es and clo sely observ es the rehearsal, ready to offer Stockw ell, '75, work on th e ramps and platform s stage movement. Later they wil l rehear se in comments on how to improve the beat. Human effort 1 enchants' production By Jon Simon a ghost. This supposed ghost where any student can "THERE ARE two or three As for props, "we go out (to be played by Matt audition, take place about preliminary steps," Ms. and find them or build them,'' When the lights go up on Grodzins) becomes friendly seven weeks before the Ambrosini said. "I work with Ms. -Ambrosini said. "The Enchanted," this year's with a young school teacher production's scheduled the actors in free movement. Meanwhile, she is choosing fall production, audiences (Barbara Bormuth). completion. They last five I look for what areas of the music. -

Adamsites Win State Achievement Awards

Adamsites Win State Achievement Awards IU Contestants Concert Features Nelson Awarded 'La Vie En Rose' Adams Soloists Will Be Prom Theme Take 18 Honors State JA Title Eighteen John Adams students The band, orchestra, and glee clubs' "La Vie En Rose" will be this year's Indiana State Junior Achievement brought scholastic honor to them Spring Concert will be given tonight Senior Prom theme, according to President of the Year is Marshall Nel selves and their school at the Indiana at 8 p.m. It will be the result of many Prom cochairmen Carol Ensign and son's new title as of Saturday, April State Achievement Contest on April Gail Levy. 25. hours of work by Adams music stu 25. dents, including the six soloists, Bon The Indiana Club will be the scene An Adams senior, Marshall has Entering the divisions of mathe nie Coker, Bill Waterson, Gene Stev of the dance which will be held May been secretary and president of the matics, English, Spanish and Latin, 15, 1959. Admission charge will be ens, Larry Thompson, Janice Weiss, First Achievers Bank, sponsored by these scholars won medals in recog $2.50 per couple. Music will be pro and Pat Scott. the First Bank and Trust Company. nition of their outstanding achieve vided by Mickey Isley. ments. Winning a gold medal, and Familiar songs from South Pacific, Marshall was recently named local Questions concerning appropriate first place in all comprehensive ma such as Bali Hai and There Is Nothin' winner in the competition for Presi dress for the occasion have come up. -

View the Viking Update

Honoring Tradition EMBRACING CHANGE CLASS OF ST. OLAF COLLEGE Class of 1969 – PRESENTS – The Viking Update in celebration of its 50th Reunion May 31 – June 2, 2019 Autobiographies and Remembrances of the Class stolaf.edu 1520 St. Olaf Avenue, Northfield, MN 55057 Advancement Division 800-776-6523 Student Editors Joshua Qualls ’19 Kassidy Korbitz ’22 Matthew Borque ’19 Student Designer Philip Shady ’20 Consulting Editor David Wee ’61, Professor Emeritus of English 50th Reunion Staff Members Ellen Draeger Cattadoris ’07 Cheri Floren Michael Kratage-Dixon Brad Hoff ’89 Printing Park Printing Inc., Minneapolis, MN Welcome to the Viking Update! Your th Reunion committee produced this commemorative yearbook in collaboration with students, faculty members, and staff at St. Olaf College. The Viking Update is the college’s gift to the Class of in honor of this milestone year. The yearbook is divided into three sections: Section I: Class Lists In the first section, you will find a complete list of everyone who submitted a bio and photo for the Viking Update. The list is alphabetized by last name while at St. Olaf. It also includes the classmate’s current name so you can find them in the Autobiographies and Photos section, which is alphabetized by current last name. Also included the class lists section: Our Other Classmates: A list of all living classmates who did not submit a bio and photo for the Viking Update. In Memoriam: A list of deceased classmates, whose bios and photos can be found in the third and final section of the Viking Update. Section II: Autobiographies and Photos Autobiographies and photos submitted by our classmates are alphabetized by current last name. -

New Website for Northern Kentucky History the Last Streetcar

Bulletin of the Kenton County Historical Society Website: www.kentoncountyhistoricalsociety.org Email: [email protected] P.O. Box 641, Covington, Kentucky 41012-0641 (859) 491-4003 July / August 2013 The Last Streetcar Covington Welcomes Liberty Bell Patricia Scott: All-American Girls Professional Baseball League New Website for Northern Kentucky History www.kentoncountyhistoricalsociety.org The Last Streetcar John E. Burns1 The year of 1890 was an eventful one for the A number of separate companies had been Covington area and indeed, for all of Kentucky. Dur- chartered to serve the various neighborhoods. The ing that year the city observed its anniversary [75 oldest of these, the Covington Street Railway Com- years], and April 9th marked the 25th anniversary of pany was commonly known as the White Line be- the Union’s victory at Appomattox Court House. cause of the color of its cars. The Covington & Cin- On May 23rd the Kentucky legislature incorporated cinnati Street Railway Company, chartered in 1870, Bromley, while an act to incorporate Holmesdale won was known as the Yellow Line, while the South Cov- the approval of the state senate, only to then become ington & Cincinnati Street Railway Company, which stalled. was chartered in 1876, adopted green as its distin- guishing color. On May 24th the outstanding thoroughbred, Bill Letcher, won the Latonia Derby; on September 8th The South Covington & Cincinnati Street Kentucky’s Constitutional Convention opened; and a Railway Company was undoubtedly the most aggres- week later, on September 15th, the Kentucky Post be- sive of the numerous local companies, and it was no gan publication. -

The Ledger and Times, July 12, 1965

Murray State's Digital Commons The Ledger & Times Newspapers 7-12-1965 The Ledger and Times, July 12, 1965 The Ledger and Times Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt Recommended Citation The Ledger and Times, "The Ledger and Times, July 12, 1965" (1965). The Ledger & Times. 4860. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt/4860 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Ledger & Times by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. N C o 11. a . , 1965 9 Selected As A Best All Round Kentucky Community Newspaper The Only rm• Largest .1. Afternoon Daily 1 U. artem- Circulation • I In Murray And Both In City Calloway County And In County beret )0 anis United Press International In Our 86th Year Murray, Ky., Monday Afternoon, July 12, 1965 Murray Population 10,100 Vol. LXXXVI No. 163 it) em. p fin 10 pin, /0 p sa. Pre-Sch400l Clinic Former Murrayan Retires After For Robertson And Lions inert College High Set International President BULLETIN Troop Strength Years In Washington, D.C. NANTUCKET, Mass, 4.1.1 — nee 36 Eight dead airmen were recover- 111 nes pee-school clinic will be held at A ed from the Atlantic Ocean to- 10 ars --- the Calloway County Health Cent. ' Miss Hope Howard Hart. of Wash- day after an Air Faroe radar 0 pm. on Thursday. July 15, at 900 ant.' D C formerly of ishrrai patrol phase washed with a crew 0. -

Hoopeston Centennial in Home Enferfainmenf

V n, * 1l 11^ fe ^g ^ n 1977.365 Souvenir booklet $1.°'* I?^B OIP HIOOI^ESTO 3Sr. 13. Lukens Bros. 19. Morey & Bros., Elevator. 25. Powell 's Drug 14. ]_Mie J. C. Davis's Hotel. Stora. 20. Hibberd Hotel, J. C. Davis, Proprlel or. 26. Hay Press, G. C. Davi*. 16. 1-ale Union Depot. 21. Goldstein, Brick Store. 27. Stock Yard. 16. P. G. Johnson. 22. M. D. Calkins, Lumber Yard. 28. Livery 17. G. H. White, Stable. l_and Agent. 23. Seam Noggle. 29. C. L. Calkua. 18. J. 1„ Mozier. 24. a. R. Weacott. ILLINOIS HISTORICAL SURVEY Souvenir Centennial Booklet: Dedicated to an Awareness of our Heritage, and a Sincere Interest in our Future! Without the complete cooperation of supporting Hoopeston businessmen, industries and organizations, our task of compiling the following booklet would not have been possible. Area friends and out-of-state businesses also played a part in financing the publication. References for information have been numerous. History of Vermilion County by Lottie Jones and Hiram Beckwith, "History Under our Feet", other volumes at Hoopeston Public Library and in- dividual research by members of the committee have been our chief sources. - ,^2iU.. Um>^' Admission: $2.50 Advance, $3.50 Door Calendar of Events 8:00 P.M. Glen Brasel Field High School "Pre-Spectacular Entertainment" Sunday July 18th Religious Heritage Day by the Antioch Teen Choir 900 P.M. "SPECTACULAR" 7:00 A.M. Noon-Church Services-All Churches Glen Brasel F leld 10:00 A.M. 4:00 P.M. -Hospitality Center Opens Thursday July 22nd Industry Day Noon McFerren Park "Reunion" 10 00 A.M. -

The B-G News May 1, 1953

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 5-1-1953 The B-G News May 1, 1953 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The B-G News May 1, 1953" (1953). BG News (Student Newspaper). 1125. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/1125 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Dance Concert, ODK APhiO Blood Bank Forum Planned For Scheduled For Tuesday This Weekend See Page Two DW&BA Gteeti State Utiiuersittj VoL37 Official Student Publication. Bowling Green, Ohio. Friday. May 1. 1953 No. 48 UAC Constitution Two-Division Forum Debates Campus Politics Mass Meeting Social Group Falls By 12-9 Vote Is Proposed Suggests 118 An attempt to form an indepcn-9 A proposal to convert the pres- dent students' political group on ent student-faculty Social Commit- campus was defeated Monday tee into a Social Policy committee night when Student Senate, by a Board, Room Prices and establish a second committee As Nominees nine to twelve vote, rejected the for social activities has been giv- constitution of United Action Con- en to Pres. Ralph W. McDonald by Over 300 Assemble gress. Increased To Meet the Council on Student Affairs. To List Candidates At the same time, Senate re- Arch II.