What's Going on in Community Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21St Century

An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. Robison Margaret Weigel Building the new field of digital media and learning The MacArthur Foundation launched its five-year, $50 million digital media and learning initiative in 2006 to help determine how digital technologies are changing the way young people learn, play, socialize, and participate in civic life.Answers are critical to developing educational and other social institutions that can meet the needs of this and future generations. The initiative is both marshaling what it is already known about the field and seeding innovation for continued growth. For more information, visit www.digitallearning.macfound.org.To engage in conversations about these projects and the field of digital learning, visit the Spotlight blog at spotlight.macfound.org. About the MacArthur Foundation The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is a private, independent grantmaking institution dedicated to helping groups and individuals foster lasting improvement in the human condition.With assets of $5.5 billion, the Foundation makes grants totaling approximately $200 million annually. For more information or to sign up for MacArthur’s monthly electronic newsletter, visit www.macfound.org. The MacArthur Foundation 140 South Dearborn Street, Suite 1200 Chicago, Illinois 60603 Tel.(312) 726-8000 www.digitallearning.macfound.org An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. -

MFF Lessons II.Cover 10.19.2

The Joint Venture Way: Lessons FOR REGIONAL REJUVENATION VOLUME 2 Joint Venture: Silicon Valley Network Joint Venture: Silicon Valley Network Designed and Produced by Jacobs Fulton Design Group Printed on recycled paper Joint Venture Acknowledgements Joint Venture was created in 1992 as a dynamic new model of regional rejuvenation. Its vision was to create a community collaborating to compete globally. Joint Venture brought people together from business, SPECIAL THANKS government, education and the community to act on regional issues To the James Irvine Family Foundation and the Morgan Family affecting economic vitality and the quality of life. Foundation for funding this extension to the original “Lessons.” PREPARED BY Phil Turner Board of Directors Jacobs Fulton Design Group As of December, 1998 CONTRIBUTORS Ruben Barrales Co-Chairpersons Tim Cuneo Mayor Susan Hammer City of San Jose Jane Decker Carol Gray Lew Platt Chairman, President & CEO, Hewlett-Packard Co. Susan Hammer Doug Henton Becky Morgan Sharon Huntsman President / CEO Bob Kraiss Connie Martinez John Melville Hon. Ruben Barrales W. Keith Kennedy San Mateo County Supervisor Watkins-Johnson Company Becky Morgan Michael Simkins Carol Bartz Paul Locatelli Autodesk Santa Clara University Glenn Toney Kim Walesh Robert L. Caret Mayor Judy Nadler San Jose State University Santa Clara Robert Cavigli John Neece Erlich-Rominger Architects Building & Construction Trades Council Leo E. Chavez Joseph Parisi Foothill-DeAnza Community Colleges Therma Jim Deichen J. Michael Patterson Bank of America PriceWaterhouseCoopers Charles M. Dostal, Jr. Condoleezza Rice Woodside Asset Management, Inc. Stanford University Katheryn M. Fong Hon. S. Joseph Simitian Pacific Gas & Electric Santa Clara County Supervisor Carl Guardino Steven J. -

Media‑Aktivisme

Media‑aktivisme Tegn, motstand og organisatoriske prosesser. Paper Tiger Tv, New York: ”Smashing the myths of the information industry” Hovedoppgave innlevert som del av Cand.Polit graden ved Sosialantropologisk Institutt UNIVERSITETET I OSLO, Våren 2007 Berit Nilsen Bua 2 Kort sammendrag av oppgaven: Denne oppgaven handler om en gruppe uavhengige Tv produsenter i New York kalt The Paper Tiger Television Collective. De lager Tv programmer med et uttalt mål om å åpne opp for større deltakelse i offentligheten ved å demokratisere tilgangen til medieproduksjon. I utgangspunktet stiller de seg kritiske til at massemedier som de hevder er en storindustri med hovedfokus på økonomisk profitt. Denne holdningen gir gruppen et politisk grunnlag for samarbeidet. De hevder selv at de ikke støtter seg til en større ideologisk plattform. Likevel tar de utgangspunkt i at ”mainstream” media oppleves som sterkt ideologisk, disiplinerende og begrensende, og kjemper med egne aktivistiske metoder mot dette. Paper Tiger kaller seg ”alternative”, og hovedmål for oppgaven er å belyse hva dette innebærer. I USA på midten av nittitallet kom en ny telekommunikasjons-lovgivning. I den forbindelse fulgte jeg aktivistenes arbeid med å synliggjøre og diskutere regjeringens motiver for lovgivningen. Temaet for oppgaven er å se på hvordan samarbeidet i Paper Tiger foregår, og måten de organiserer seg på. Gruppen definerer seg selv som en åpen og fri enhet uten leder eller rammebetingelser, der medlemmene kan komme og gå, og gjøre som de vil. Ut ifra denne definisjonen er det kanskje et paradoks at gruppen fortsatt er i drift, etter 25 år. I oppgaven ønsker jeg å sette søkelys på hva som gjør at gruppen fortsatt eksisterer. -

Andrew Pinçon

eChicago 2009 Kate Williams, editor Proceedings of the third eChicago symposium held at Dominican University, River Forest, Illinois April 2-3, 2009 A monograph published by the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign Graduate Schools of Library and Information Science © 2010 The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois ISBN-10: 0-87845-130-7 ISBN-13: 978-0-87845-130-2 The University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign Graduate School of Library and Information Science has a distinguished tradition of publishing high-quality publications for the field of LIS and actively produces Library Trends and The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books. Our 50 year publishing history includes scholarly and practical publications that address current issues and also serve as historical archives. Here you can find quality books, journals, papers, and conference proceedings for teaching, scholarly reading, and daily application. This and other titles are available through the Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship (IDEALS) at http://www.ideals.uiuc.edu/handle/2142/154 To link directly to all the eChicago proceedings, visit http://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/4605 Keep up to date on eChicago at http://echicago.illinois.edu eChicago 2009 Cybernavigating our Cultures Introduction—Kate Williams with Chris Hagar................................................................. 1 Symposium program........................................................................................................... 5 Photo -

© 2020 Kaitlyn Wentz All Rights Reserved

© 2020 KAITLYN WENTZ ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ARTS AND CULTURE INFLUENCERS: TWO PHILANTHROPISTS’ IMPACT ON THE NORTHEAST OHIO REGION A Thesis PresenteD to The GraDuate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts KAITLYN WENTZ May, 2020 ARTS AND CULTURE INFLUENCERS: TWO PHILANTHROPISTS’ IMPACT ON THE NORTHEAST OHIO REGION Kaitlyn Wentz Thesis ApproveD: AccepteD: ______________________________ ___________________________ Advisor School Director James Slowiak Dr. Marc ReeD ______________________________ ___________________________ Committee Member Interim Dean of the College ArnolD Tunstall Dr. LinDa Subich ______________________________ ___________________________ Committee Member Acting Dean of the GraDuate Courtney Cable School Dr. Marnie SaunDers ___________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT In a time of constant threat to funDing, elimination of the National EnDowment, anD competition over resources, philanthropy in the arts anD culture sector is inDispensable to the vibrancy anD economic Development of a city’s core. The arts anD culture sector is consiDereD to take away from an economy’s financial resources. However, it is the exact opposite. It is a thriving sector that contributes to the economy by creating jobs, spenDing money at local businesses, anD bringing in cultural tourists. FreD BiDwell anD Rick Rogers have a long history of philanthropy in this sector, anD their DemonstrateD support has leD to efforts of revitalization, vibrancy, anD Dollars spent in the cities of Akron anD ClevelanD. This thesis explores the history, issues, and successes of the two cultural proDucers’ philanthropy efforts in the sector anD the impact that their support has brought to the Northeast Ohio region. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. -

Assessing the Radical Democracy of Indymedia: Discursive, Technical, and Institutional Constructions

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 8-22-2006 Assessing the Radical Democracy of Indymedia: Discursive, Technical, and Institutional Constructions Victor Pickard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pickard, V. (2006). Assessing the Radical Democracy of Indymedia: Discursive, Technical, and Institutional Constructions. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 23 (1), 19-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 07393180600570691 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/445 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Assessing the Radical Democracy of Indymedia: Discursive, Technical, and Institutional Constructions Abstract This study examines the radical democratic principles manifest in Indymedia’s discursive, technical, and institutional practices. By focusing on a case study of the Seattle Independent Media Center and contextualizing it within theories and critiques of radical democracy, this article fleshes out strengths, weaknesses, and recurring tensions endemic to Indymedia’s internet-based activism. These findings have important implications for alternative media making and radical politics in general. Keywords alternative media, cyberactivism, democratic theory, independent media centers, indymedia, networks, radical democracy, social movements Disciplines Communication -

Checklist for Returning to Community Radio Stations

RETURNING TO COMMUNITY RADIO STATIONS - CHECKLIST As the various states and territories progressively lift social distancing requirements, community radio station boards and management committees should consider their roadmap for safe return. Every station will be different – with each returning in the way that is best suited for their situation. Public health remains the most important consideration. Following advice from Federal Government health authorities and any state/territory regulation is critical. Organisational Consideration Action Y/N Access to information 1. Do you and your organisation have all relevant facts about COVID-19? 2. Is your organisation staying up to date? 3. Check official information sources including: • Australian Government Department of Health: www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel- coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert • World Health Organisation: www.who.int • Safe Work Australia ww.safeworkaustralia.org.au 4. Relevant State/Territory/local government websites. Governance 5. Is station board and staff clear on who within your organisation will make and implement decisions on returning to the studio/office? 6. Does everyone within your organisation understand their role? 7. Has your organisation nominated a COVID-19 Safety Coordinator to oversee delivery of your return plan? You can locate a description of this role on CBAAs website. Strategy 8. Has your organisation reviewed its strategic plan for COVID-19 considerations? 9. Has your organisation defined what success looks like? 10. Does your organisation need to amend fixtures, broadcasting and training rules or activities to ensure physical distancing? Financial 11. Does your organisation know what its new safety/return to studio measures will cost? 12. -

Public Media – Pubic Broadcasting System (PBS)

SUPPORTING PUBLIC AND COMMUNITY MEDIA ACTION NEEDED We urge Congress to: Restore public broadcasting funding to the FY 2013 appropriation level of $445 million through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). Pass the Community Access Preservation Act (CAP Act) to preserve public, educational, and governmental (PEG) non-commercial cable channels for local communities. OVERVIEW—PUBLIC AND COMMUNITY MEDIA Public media consists of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), National Public Radio (NPR), and more than 1,000 local public broadcasting stations. Community media is comprised of public, educational, and government (PEG) cable access TV and community radio stations. Both public and community media have a long history of presenting local, regional, and national nonprofit arts programming, a great majority of which is not available on commercial channels. These organizations play a unique role in bringing both classics and contemporary works to the American public. All of these systems exist because of federal funding or legislation. TALKING POINTS— CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING In creating America’s unique public broadcasting system, Congress acknowledged public broadcasting’s role in transmitting arts and culture: “It is in the public interest to encourage the growth and development of public radio and television broadcasting, including the use of such media for instructional, educational, and cultural purposes.” And Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) is the vehicle through which Congress has chosen to promote noncommercial public telecommunications. CPB does not produce or broadcast programs. The vast majority of funding through CPB goes directly to local public broadcast stations in the form of Community Service Grants. The federal portion of the average public station’s revenue is approximately 10–15 percent. -

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008 Jan

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008 Jan. 31 – May 31, 2015 Exhibition Checklist DOWN AT CONEY ISLE, 1861-94 1. Sanford Robinson Gifford The Beach at Coney Island, 1866 Oil on canvas 10 x 20 inches Courtesy of Jonathan Boos 2. Francis Augustus Silva Schooner "Progress" Wrecked at Coney Island, July 4, 1874, 1875 Oil on canvas 20 x 38 1/4 inches Manoogian Collection, Michigan 3. John Mackie Falconer Coney Island Huts, 1879 Oil on paper board 9 5/8 x 13 3/4 inches Brooklyn Historical Society, M1974.167 4. Samuel S. Carr Beach Scene, c. 1879 Oil on canvas 12 x 20 inches Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, Bequest of Annie Swan Coburn (Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn), 1934:3-10 5. Samuel S. Carr Beach Scene with Acrobats, c. 1879-81 Oil on canvas 6 x 9 inches Collection Max N. Berry, Washington, D.C. 6. William Merritt Chase At the Shore, c. 1884 Oil on canvas 22 1/4 x 34 1/4 inches Private Collection Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art Page 1 of 19 Exhibition Checklist, Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861 – 2008 12-15-14-ay 7. John Henry Twachtman Dunes Back of Coney Island, c. 1880 Oil on canvas 13 7/8 x 19 7/8 inches Frye Art Museum, Seattle, 1956.010 8. William Merritt Chase Landscape, near Coney Island, c. 1886 Oil on panel 8 1/8 x 12 5/8 inches The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, N.Y., Gift of Mary H. Beeman to the Pruyn Family Collection, 1995.12.7 9. -

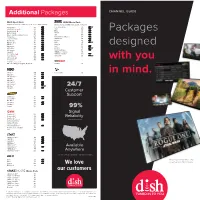

Packages Designed with You in Mind

Additional PackagesWe loveWe our love customers our customersCHANNEL GUIDE Multi-Sport Pack ™ DISH Movie Pack Requires subscription to America’s Top 120 Plus or higher24/7 package. 15 movie24/7 channels and 1000s99% of titles available On Demand.99% beIN SPORTS SAP 392 Crime & Investigation 249 beIN SPORTS en Español 873 CustomerEPIXCustomer 1 Signal380 Signal Big Ten Network 405 EPIX 2 381 * * Packages Big Ten Network 410 SupportEPIX SupportHits Reliability382Reliability Bases Loaded/Buzzer Beater/Goal Line 403We love FXMour customers384 FOX Sports 2 149 Hallmark Movies & Mysteries 187 1 HDNet Movies *Based on nationwide130 study of signal reception by DISH customersAvailable Longhorn Network 407 *Based on nationwide study of signal reception by DISH customersAvailable MLB Network 152 IndiePlex 378 MLB Strike Zone 153 MGM 385 Anywhere NBA TV SAP 156 MoviePlex 377 Anywhere NFL Network 154 PixL SAP 388 designed NFL RedZone 24/7155 99%RetroPlex 379 NHL Network 157 Sony Movie Channel 386 Outside TV Customer390 SignalSTARZ Encore Suspense 344 STARZ Kids & Family SAP 356 Pac-12 Network 406 * Pac-12 Network 409 Universal HD 247 SEC Network Support404 Reliability SEC Network SAP 408 with you 1 Only HD for live events. *Based on nationwide study of signal reception by DISH customersAvailable Plus over 25 Regional Sports Networks TheBlaze Anywhere212 HBO (E) SAP 300 Fox Soccer Plus 391 HBO2 (E) SAP 301 in mind. HBO Signature SAP 302 HBO (W) SAP 303 HBO2 (W) SAP 304 HBO Family SAP 305 HBO Comedy SAP 307 HBO Zone SAP 308 24/7 24/7 HBO Latino 309 -

Solon Springs Channel Lineup Choose the Package That fits Your Life

Solon Springs Channel Lineup Choose the package that fits your life. B C P U Basic Choice Plus Ultimate 10 + Local Channels 60 + Channels 130 + Channels 160 + Channels including Locals including Locals including Locals Basic 2 | 2.1 Minnesota Channel 6 | 6.1 C-SPAN 10 | 10.1 WDIO - ABC HD 3 | 3.1 QVC 7 | 7.1 PBS HD 11 | 11.1 KQDS - FOX HD 4 | 4.1 The Weather Channel 8 | 8.1 WDIO - MeTV 12 | 12.1 KBJR - NBC HD 5 | 5.1 KBJR - CBS HD 9 | 9.1 KBJR - MyNetwork Choice 14 | 14.1 RFD 29 | 29.1 TLC 45 | 45.1 Comedy TV 61 | 61.1 Big Ten Network 15 | 15.1 TBS 30 | 30.1 FX 46 | 46.1 AMC 62 | 62.1 MSNBC 16 | 16.1 Lifetime 32 | 32.1 Fox Sports 1 47 | 47.1 E! 63 | 63.1 Evine 17 | 17.1 National Geographic 33 | 33.1 Fox Sports Wisconsin 48 | 48.1 NBC Sports Network 64 | 64.1 C-SPAN 2 18 | 18.1 Freeform 34 | 34.1 ESPN 2 49 | 49.1 Outdoor Channel 65 | 65.1 INSP 19 | 19.1 Cartoon Network 35 | 35.1 ESPN 50 | 50.1 Sportsman Channel 66 | 66.1 EWTN 20 | 20.1 SyFy 36 | 36.1 HLN 51 | 51.1 Hallmark Channel 67 | 67.1 Disney XD 21 | 21.1 TCM 37 | 37.1 Fox News Channel 52 | 52.1 HGTV 68 | 68.1 HSN 22 | 22.1 Disney Channel 38 | 38.1 Tru TV 53 | 53.1 Oxygen 70 | 70.1 Bravo 23 | 23.1 FXX 39 | 39.1 CNN 55 | 55.1 Travel Channel 71 | 71.1 ID 24 | 24.1 USA Network 40 | 40.1 Food Network 56 | 56.1 Discovery Channel 74 | 74.1 POP 25 | 25.1 A&E 41 | 41.1 Revolt 57 | 57.1 Animal Planet 75 | 74.1 OWN 26 | 26.1 TNT 42 | 42.1 Disney Junior 59 | 59.1 History Channel 76 | 76.1 Fox Business Network 27 | 27.1 WGN 44 | 44.1 CNBC 60 | 60.1 WE TV 97 | 97.1 Science Channel 28 | 28.1 Fido -

200312.Cover

UPCOMING EVENTS A GOOD TIME FOR A GOOD CAUSE The Public i,a project of the Urbana-Cham- Dance Party with the Noisy Gators paign Independent Media Center, is an (cajun/zydeco dance band with Tom Turino) independent, collectively-run, community- With winter pressing in there’s no better time for a Dance Party with great food and oriented publication that provides a forum friends. On Saturday, December 13th AWARE will host the Noisy Gators (one of C-U’s for topics underreported and voices under- best local dance bands). There will be lots of space to dance, food, drinks, and friends. And represented in the dominant media. All best of all, the proceeds from the Benefit will all be donated to help those who’ve been hurt contributors to the paper are volunteers. by war - both here at home and in Iraq. Hope to see you there! Everyone is welcome and encouraged to sub- Where: The Offices of On the Job Consulting (OJC), 115 West Main, 2F in downtown mit articles or story ideas to the editorial col- Urbana (across from Cinema Gallery) lective. We prefer, but do not necessarily When: Saturday, December 13th, 8-11pm restrict ourselves to, articles on issues of local Sliding Scale donation: $5 - $20+ Dec-Jan 2003-4 • V3 #10 impact written by authors with local ties. All Proceeds benefit Oxfam Iraq (humanitarian aid to Iraqis) and the Red Cross Armed Forces FREE! EDITORS/FACILITATORS: Emergency Services Fund (help for veterans and military families). Xian Barrett Sponsored by AWARE (Anti-War Anti-Racism Effort) Lisa Chason Darrin Drda EDUCATION OR INCARCERATION? ZINE SLAM WITH IMPROV MUSIC Jeremy Engels SCHOOLS AND PRISONS IN A Linda Evans PUNISHING DEMOCRACY Belden Fields Saturday, December 13 6:30 PM Meghan Krausch An Interdisciplinary Conference hosted by at the IMC, 218 W.