Case Number: 3982/2016 in the Matter Between: NELIE SMITH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tendense En Tematologie in Populêre Werke Oor Suid- Afrikaanse Rugby, 1948-1995: ’N Historiografiese Studie

Tendense en tematologie in populêre werke oor Suid- Afrikaanse rugby, 1948-1995: ’n Historiografiese studie. Wouter de Wet Tesis voorgelê in ooreenkoms met die vereistes vir die graad MA (Geskiedenis) aan die Universiteit van Stellenbosch Studieleier: Prof. A.M. Grundlingh December 2013 [1] Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Verklaring: Ek, die ondergetekende, erken hiermee dat die werk wat in hierdie navorsing/verhandeling vervat is, my eie, oorspronklike werk is en dat ek dit voorheen nie in sy geheel, of gedeeltelik, by enige ander universiteit vir ’n graad ingehandig het nie. Handtekening: WJ de Wet Datum: 2 September 2013 Copyright © 2013 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved [2] Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Opsomming Hierdie studie is ’n historiografiese studie van populêre rugby geskiedskrywing, en dek die jare 1948 tot 1995. Die doel is om te dui op hoe dié sport in populêre skrywes uitgebeeld is. Die fokus gaan val op die twee vorme van populêre geskiedskrywing in hierdie tydperk, naamlik algemene rugbygeskiedenisboeke en biografiese werke. Die manier hoe hierdie verhandeling te werk gaan, is om tendense en tematologie in hierdie werke te identifiseer en die verandering daarvan oor die jare, na te volg. Hierdie werk lê op die breekvlak tussen ’n studie van die geskiedenis en die letterkunde. Deur die gewilde rugby skrywes inhoudelik en letterkundig in fyn detail te bestudeer, gaan lig op die veranderende tendense en tematologie gewerp word. Aanhalings word deurgans ingesluit en bespreek om die ontwikkeling van die populêre rugby geskiedskrywing oor die jare te verduidelik. Deur op hierdie kompleksiteite klem te lê, poog die studie om ’n bydrae te lewer tot die steeds ontwikkelende veld van Suid- Afrikaanse sportgeskiedenis. -

Roadmap for UFS's Future

RoadmapRoadmap forfor UFS’sUFS’s futurefuture NuweNuwe tydvaktydvak breekbreek aanaan Redakteur / Editor: Leatitia Pienaar Tel: +27 51 401 9188 Faks / fax: +27 051 444 6393 [email protected] UV-webblad / UFS Website: www.ufs.ac.za inhoud Julie 2007 Jaargang 55 nr 2 Produksie / Production Uitleg / Layout Chrysalis Advertising and Publishing, Nuus/News Bloemfontein 4 Diversiteit in koshuise hou voordele in vir studente 082 728 4860 6 Rektor se aanstelling by UV verleng [email protected] 7 Lifestyle diseases biggest killer of South Africans 8 UFS farms play vital role Drukwerk / Printing 12 ‘We get the number of criminals we deserve’ PrintAbility, Pinetown 18 Marion die pols van die aarde 24 R30-m injected into research at the UFS Bult, nuustydskrif van die Universiteit 27 Students bring campus shooting closer to UFS van die Vrystaat, word uitgegee deur die Afdeling: Strategiese Kommunikasie aan die UV. Menings wat in die Monitor publikasie gelug word, weerspieël nie noodwendig die van die Redakteur, 26 Nog ’n titel vir SR-president die Afdeling of die UV nie. Bult word 29 Stalsprys aan Dave Lubbe onder oudstudente, donateurs, sake- 31 Regstudente onder bestes in die wêreld en regeringsleiers, meningsvormers en Kovsie-vriende versprei. Artikels mag met die nodige erkenning elders gebruik word. Rig navrae hieroor aan Our corporate friends die Redakteur. 33 Gauteng corporate donors: thanks! 34 Making science fun thanks to BP Bult, news magazine of the University of the Free State, is published by the Division: Strategic Communications at the UFS. Opinions expressed in the Alumni publication are not necessarily those of the Editor, the Division or the UFS. -

The Long Shadow of the 1981 Springbok Tour of New Zealand and the United States of America

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository “Barbed-Wire Boks”: The Long Shadow of the 1981 Springbok Tour of New Zealand and the United States of America by Sebastian Johann Shore Potgieter Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts and Social Sciences in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Albert Grundlingh March 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT In 1981, during the height of apartheid, the South African national rugby team, the Springboks, toured to New Zealand and the United States of America. In South Africa, the tour was expected to reopen the doors to international competition for the Springboks after an anti-apartheid sporting boycott had forced the sport into relative isolation during the 1970s. In the face of much international condemnation, the Springboks toured to New Zealand and the USA in 1981 where they encountered large and often violent demonstrations as those who opposed the tour attempted to scuttle it. -

Bultissue 2 • 2012 Nuustydskrif

BultIssue 2 • 2012 Nuustydskrif | News magazine Bult REDAKTEUR | EDITOR Leatitia Pienaar Division: Strategic Communication [email protected] Posbus | PO Box 339 Bloemfontein 9300 South Africa www.ufs.ac.za Tel: +27(0) 51 401 9188 Cell: +27(0) 83 677 6042 Fax: +27(0) 51 444 6393 PRODUKSIE | PRODUCTION Ontwerp | Design SUN MeDIA Bloemfontein Tel: +27(0) 51 430 0459 [email protected] Menings wat in die publikasie gelug word, weerspieël nie noodwendig die van die Redakteur, die afdeling of die universiteit nie. Bult word onder oudstudente, donateurs, sake- en regeringsleiers, meningsvormers en Kovsievriende versprei. Artikels kan met die nodige erkenning elders gebruik word. Rig navrae Nuus News hieroor aan die Redakteur. Strategic plan is the map for the next five years 4 Opinions expressed in the publication NRF-rated researchers grow strongly 6 are not necessarily those of the Editor, UFS gets three NRF chairs to boost research 7 the division or the university. Bult is sent to alumni, donors, business and Law students learn from the best of the best in the industry 12 government leaders, opinion formers and Kovsie friends. Articles can be Elzmarie honoured internationally for economic education 22 published elsewhere, with the necessary acknowledgement. Contact the Editor in Vir Argitektuur was 2012 ’n jaar om te vier 24 this regard. Kampusse ’n miernes van bou-bedrywighede 26 Aerial photograph of the Bloemfontein Campus 28 Thought-provoking lectures at Business School 30 Front page: The lush gardens on the Bloemfontein Campus. - Photo: Johan Roux How to read the Q-tags: Download the Q-tag reader on your cellphone and follow the instructions. -

Bloe?,Ifontein

!: '-1: /i 5$ ia BLOE?,IFONTEIN iY r= € E4B a6 I :-r- @tty =7h,0[[rSP 'N PARALLELMEDIUM.SKOOL VIR SEUNS CESTIC i855 s^bootbluU ffilsqu'tnt EST. 1855 Gtty t,nllpqo A PARALLEL MEDIUM SCHOOL FOR BOYS t* * BeDshstt - @Dftoriul Stsff Redakteur - Editor Mnr./Mr. J. L. CRONJE. B esi ghei dsb e st uurd er - B u i ne ss M atuger Mnr./Mr. K. PIENAAR Komitee - Committee Messrs./Mnre. H. EARP, L. SHEPSTONE, A. SIEBERHAGEN, P. FERREIRA, F. RAUTENBACH, A. A. MARAIS, J. STRYDOM R. BARRY, G. SABBAG- HA. L. KRUGER, D. BREYTENBACH, P. STRYDOM EN MEJ. P. DE VIL- LIERS Advertisements - A dvertensiewerwers E. POOLMAN. D. LOUW, P. v. d. WALT. Volume 44 November 1963 No. 9I PERSONEEL - STAFF '{ Agterste ry (l.n.r.): Mnre. N. v. d. Wolt, N. du Plcssis, D. C. de Joger, J. W. Fourie, J. L. Cronj6, M. G. Heyns, K. J. Picnoo-, F. Mullcr, J. Rossouw, D. Bezuidenhout, A. A. Morois Sccond row: Messrs. D. Breytenboch, F. Routenb,.lch, J. Lcurens, L. Kruger, G. Sqbbogho, K. Strydom, N. E. Cronle, [). de Wocl, F. Kruger, P. Strydom, G. Cilliers, S. Strydom. Derde ry: Mej . M. E. v. Scholkwyk, mnre. A. M. Mullcr, J. C. Rosseou, R. Cilliers, R. Borry, J. Steenkomp, D. 5chorcgevcl, N. Fourie, A. H. Morois, J. C. B. Cloossen, J. P. C. Strydom, P. Bcrnord, F. J. Wesscls, mev. R. Edeling. Fourth row: Mr. L. T. Shepstone, miss J. Myburgh, miss A. Semcyn, miss A. Fourie, mrs. l. E. Eloff, messrs. M. G. Bonnct, D Morquord, A. Sieberhogcn, C. -

Bayern’S Milan Date Would Hamper Germany’S Euro Plans

NBA | Page 7 TTENNISENNIS | Page 11 Curry-less Federer pulls Warriors out of Madrid whip Trail with back Blazers injury Tuesday, May 3, 2016 CRICKET Rajab 26, 1437 AH Pathan is Knight GULF TIMES of the night as KKR win SPORT Page 5 AFC CHAMPIONS LEAGUE El Jaish confi dent as they take on Saudi’s Al Ahli ‘We want to continue our good performances and hopefully we can get the three points tomorrow’ Agencies Jeddah resh from their recent success in the prestigious Qatar Cup, El Jaish are brimming with con- fi dence as they take on Saudi FArabia’s Al Ahli in the Asian Champi- ons League today. With 10 points from fi ve matches, El Jaish are already assured of the top place in Group D, but Al Ahli will have everything to play for as they target a spot in the last 16 by fi nishing second. For that to happen, however, the Saudi giants, who have six points from fi ve matches, will have to beat El Jaish and also hope UAE’s Al Ain don’t defeat Uzbekistan’s Nasaf in the other Group D fi xture today. As things stand now, Al Ain, Al Ahli and Nasaf are all in the race for the sec- ond spot, but El Jaish coach Sabri Lam- ouchi was in no mood for any conces- sions on the eve of the match yesterday. “It will be defi nitely a hard match,” said Lamouchi. “We are up against one of the best teams in Saudi Arabia, who have re- cently won the league title. -

Die 1981 Springbok-Rugbytoer Na Nieu- Seeland: Die Katalisator in Die Stryd Teen Apartheid in Suid-Afrikaanse Rugby

JOERNAAL/JOURNAL BARNARD/RADEMEYER DIE 1981 SPRINGBOK-RUGBYTOER NA NIEU- SEELAND: DIE KATALISATOR IN DIE STRYD TEEN APARTHEID IN SUID-AFRIKAANSE RUGBY Leo Barnard en Cobus Rademeyer1 Summary In analysing the history of South African sport the 1981-Springbok rugby tour to New Zealand is always mentioned as one of the turning points in the struggle against apartheid in South African sport. Due to the nature of the segregated sports development in South Africa, there has always been a racial undertone in the rugby relations between South Africa and New Zealand, but the All Blacks have always been one of South Africa's closest rugby allies. The 1981 tour, however, changed all of this, mainly because it caused a rift within the New Zealand rugby community and led to strong political undertones that nearly halted the tour. Various anti-apartheid groupings, the New Zealand police force and the rugby-mad New Zealand people came in confrontation with one another during the tour. This confrontation was orchestrated by 'behind the scenes' developments, and attempts by the anti-apartheid organisations to dismantle apartheid in South African sport. By disrupting and almost stopping the tour, these orchestrated attempts by the anti-apartheid movements set an example for future actions against apartheid in South African sport. These actions not only stunned the rugby public in New Zealand, but television brought these visuals to the homes of many white South Africans for whom it was their first real experience of the boycott actions against South African sport. _______________ Die veelbesproke Springbokrugbytoer na Nieu-Seeland in 1981 word algemeen aanvaar as die katalisator vir buitelandse verset teen Suid-Afrikaanse rugby gedurende die tagtigerjare. -

Looking for a Job Or Someone to Fill a Position?

THURSDAY 5 May 2016 NEWS YOU CAN USE FREE GEMEENSKAP COMMUNITY BUSINESS www.bloemfonteincourant.co.za ADHD-medikasie kan An investigation into Botshabelo Dekaan as waarnemende beendigtheid in jong RDP housing projects Industrial Park to regter in die Bloemfonteinse kinders beïnvloed in Mangaung boost investment BLADSY 3 PAGE 4 PAGE 10 Hoë Hof aangestel Another bad apple in FS Education REFILWE GAESWE taking up the place of these ghost workers – and be paid a lump sum of close to R21 Allegations of fraud, corruption and 000 for back pay,” they say. nepotism have surfaced within the Free Employees say new recruits have been State Department of Education. hired through political connections, At the centre of the controversy is the receiving higher salaries than those who department’s warehouse for stationery have been working there for years. and learning material. The appointment Despite the department’s insistence that of workers here has been the reason for there are no funds for the permanent the Public Servants Association of South employment of workers, new recruits keep Africa (PSA) declaring a dispute with the fl owing in without any vacancies being department. advertised. Provincial manager, Gerhard Koorts, says Insiders say these employees brag to their they are unhappy that workers here have colleagues about their “back pay” and been contract-appointed for years. “This is have indicated they have to pay a portion a contravention of labour laws and despite of their lump sum as kickback to senior registering grievances with the department, offi cials who secured their appointment. it failed to address the issue.” He says the The contract employees say they have PSA has now registered a complaint at the pleaded with the department for years to be CCMA. -

The Long Shadow of the 1981 Springbok Tour of New Zealand and the United States of America

“Barbed-Wire Boks”: The Long Shadow of the 1981 Springbok Tour of New Zealand and the United States of America by Sebastian Johann Shore Potgieter Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts and Social Sciences in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Albert Grundlingh March 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT In 1981, during the height of apartheid, the South African national rugby team, the Springboks, toured to New Zealand and the United States of America. In South Africa, the tour was expected to reopen the doors to international competition for the Springboks after an anti-apartheid sporting boycott had forced the sport into relative isolation during the 1970s. In the face of much international condemnation, the Springboks toured to New Zealand and the USA in 1981 where they encountered large and often violent demonstrations as those who opposed the tour attempted to scuttle it. For the duration of the tour, New Zealand was plunged into a divisive state of chaos as police and protestors clashed outside heavily fortified rugby stadiums. -

3 October 1994.Pdf

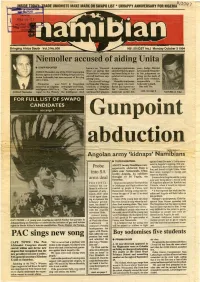

- UNIONISTS MAKE MARK ON SWAPO LIST * UNHAPPY ANNIVERSARY FOR NIGE~IA1\ 00 'f 7 Niemoller accused' of aiiJing Unita • SfAFFREPORTER known a. I'Genel'al Acompanyspokesmao year. Judge Barold J08AN Nlemoller, one o(tbe CtvU Cooperation ltha" 8$ saying tbat admitted thatthe plane Levy namedl'Jiemol1er NtemoUer's rompeD}" had been flyJng to An~ in his Judgement as BUre8_Uagents accusedofkllUngSWapo acti~ Anton Lubowsld, has been acaiSed of CetTfing alrcrafl had been sup~ gola but not to support being. OD the basis or aid t. Unlta. plYIng Vnlta. Voila. prima Jade evidence, The aircraft belongs Nltmollerls-a former responsible for NlernolJer was Mall & Guardian to Nlemoller Pharma· CCB agent wbo testi· Lubowski's death. named by- an'.~:.!?la. b newspaper on Friday. tied at tl}e inquest into Itba told The The tbe murder or earlier this cont. on page Z oint uction - __ .; e Angolan army 'kidnaps' ami"b" laD S fr==:::===="'1l • TYAPPA NAt.fJTEWA against lonas Savimbi's Uni ta move ABOUT twenty Namibians were ment in Angola's ongoing civil war. Probe Namibians have been abducted be apparently abducted from a fore and forced to fighl Unila. Some into SA place near Namacunde, l Skm have since managed to escape and inside Angola, by soldiers return to Namibia. thought to be Fapla, on Sources from Angola said the young arms deal Saturday. men were being taken to the far north PRETORIA: Sources who spoke 10 The Namibian of Angola to places like Kanfufu and Annscor has con at Oshikango said Fapla soldiers has Cabinda, where it would be impossi - fmned it sold a con rounded up people al Parasa.