Power Centers in Upper Burma (C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Myanmar] Research Society Brief History of the Burma](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2607/myanmar-research-society-brief-history-of-the-burma-2607.webp)

[Myanmar] Research Society Brief History of the Burma

Analytical Study on the Publications edited and published by the Burma [Myanmar] Research Society Ni Win Zaw Abstract The Burma Research Society (BRS) was founded on 29th. March 1910 and had a programmee to Publish, in printed book-form, important texts from Myanmar palm-leaf and parabike paper manuscripts. The BRS did most valuable work in carefully editing and publishing many old manuscripts texts. The famous Myanmar scholar Dr. Pe Maung Tin served as the BRS General Editor for its Text Program from the early 1920s to about 1940 when the Society had to cease its activities due to the Second World War. After Second World War U Wun (Min Thu Wun) and U Tin E made energetic efforts for the BRS. U Wun served asa the General Editor for the New Series. This Paper describes authors, editors, editions, printing presses, publishing dates, cover style, arrangements, physical descriptions, series numbers, appendixes, indexes, footnotes, and subjects of these books.And also it identifies the performance of editors who were prominent Myanmar and Pali scholars like Saya Lin, Saya Pwa, U Po Sein, BaganWundauk U Tin, U Lu Pe Win, U Chan Mya, U Wun, U Thein Han, and others. Moreover,abilities of ancient Myanmar authors and role of old Myanmar literature are investigated and expressed in this paper. Brief History of the Burma (Myanmar ) Research Society The Burma Research Society was founded on 29th. March 1910 at Bernard Free Library in Rangoon (Yangon) by J.S.Furnivall who was a member of the India Civil Service stationed in Myanmar together with some learned Myanmar officials like U May Oung.1After Opening the Rangoon (Yangon) University, the headquarter of the Society was located at the Rangoon University (Universities' Central Library), from about 1930-1980. -

Some Documented Cases of Linguistic Change

APPENDIX I SOME DOCUMENTED CASES OF LINGUISTIC CHANGE 1. Jinghpaw become Shan The first European to visit Hkamti Long (Putao) was Wilcox in 1828. He recorded of the Shan area that 'the mass of the labouring population is of the Kha-phok tribe whose dialect is closely allied to the Singpho'. Other non-Shan dependents of the Shans were the Kha-lang with villages on the Nam Lang 'whose language more nearly resembles that of the Singpho than that of the Nogmung tribe who are on the Nam Tisang'. The prefix 'Kha-' in Hkamti Shan denotes a serf: 'phok' (hpaw) is a term applied by Maru and Hkamti Shans to Jinghpaw. Kha-phok therefore means 'serf Jinghpaw'. In 1925 Barnard described Hkamti Long as he knew it. He noted that the Shan population included a substantial serf class (lok hka) divided into various 'tribes' which he supposes to have been of Tibetan origin, but he remarks: 'I have not been able to obtain even a small vocabulary of their language as they have been absorbed into the Shans whose language and dress they have completely adopted.' It would appear that Barnard's lok hka must include the descendants of Wilcox's Kha-phok and Kha-lang. The inhabitants of 'the villages on the Nam Lang' now speak Shan; but the Jinghpaw-speaking population on the other side of the Mali Hka-who call them selves Duleng-claim to be related to these 'Shans' of the Nam Lang. Of the Nogmung, Barnard recorded: '(They) are gradually being absorbed by the Shans . -

Paper Format for the International

Internet Journal of Society for Social Management Systems ISSN: ORIGINAL ARTICLE Structure of Ancient Mrauk U Kyaw Sann Oo1*, Masataka Takagi2 1 Advanced Agricultural Engineering Co., Ltd., 19 Myay Nu Street, Sanchaung Township, Yangon 11111, MYANMAR 2 School of Systems Engineering, Kochi University of Technology 185 Tosayamadacho-Miyanokuchi, Kami, Kochi, 782-8502, JAPAN *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Satellite Remote Sensing helps to look the existing ground features from the above since mid of 20th century. Moreover, important geographic information of the ground features could be recorded and analysis using GIS. On the world, many ancient cities are ruining not only by the times and weathering but also destroyed by human being. Fortunately, some important ancient cities structures are still resilience under the soil. Mrauk U ancient city's walls are also remained resiliently. Those structures could be recorded using RS/GIS technique. Based on the GIS recorded database, the information are generated such as archeological information, socio-cultural information and ancient irrigation system to use as agricultural and fortress. Implemented GIS database and analysis information could be used as input data for world heritage application of Ancient Mrauk U. Once the site become world heritage, tourism sector businesses will be developed and social standard will be improved. Finally, this study will highlight the phenomena western trade interaction with east ward. Keywords: Ancient, Fortress, Agriculture, Heritage 1. Introduction Mrauk U, the last capital of Rakhine, lies on Mrauk U lies about sixty-five kilometer from the rocky ranges of hills which are located the coast of Bangle, although the largest ocean- between the watershed of Lemro and Kaladan going ships of that period could reach her port rivers. -

AROUND MANDALAY You Cansnoopaboutpottery Factories

© Lonely Planet Publications 276 Around Mandalay What puts Mandalay on most travellers’ maps looms outside its doors – former capitals with battered stupas and palace walls lost in palm-rimmed rice fields where locals scoot by in slow-moving horse carts. Most of it is easy day-trip potential. In Amarapura, for-hire rowboats drift by a three-quarter-mile teak-pole bridge used by hundreds of monks and fishers carrying their day’s catch home. At the canal-made island capital of Inwa (Ava), a flatbed ferry then a horse cart leads visitors to a handful of ancient sites surrounded by village life. In Mingun – a boat ride up the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) from Mandalay – steps lead up a battered stupa more massive than any other…and yet only a AROUND MANDALAY third finished. At one of Myanmar’s most religious destinations, Sagaing’s temple-studded hills offer room to explore, space to meditate and views of the Ayeyarwady. Further out of town, northwest of Mandalay in Sagaing District, are a couple of towns – real ones, the kind where wide-eyed locals sometimes slip into approving laughter at your mere presence – that require overnight stays. Four hours west of Mandalay, Monywa is near a carnivalesque pagoda and hundreds of cave temples carved from a buddha-shaped moun- tain; further east, Shwebo is further off the travelways, a stupa-filled town where Myanmar’s last dynasty kicked off; nearby is Kyaukmyaung, a riverside town devoted to pottery, where you can snoop about pottery factories. HIGHLIGHTS Join the monk parade crossing the world’s longest -

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) Buddhism Is an Integral Part of Burmese Culture

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) 2 Volumes By Charlotte Kendrick Galloway A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University November 2006 ii Declaration I declare that to the best of my knowledge, unless where cited, this thesis is my own original work. Signed: Date: Charlotte Kendrick Galloway iii Acknowledgments There are a number of people whose assistance, advice and general support, has enabled me to complete my research: Dr Alexandra Green, Dr Bob Hudson, Dr Pamela Gutman, Dick Richards, Dr Tilman Frasch, Sylvia Fraser- Lu, Dr Royce Wiles, Dr Don Stadtner, Dr Catherine Raymond, Prof Michael Greenhalgh, Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi, U Aung Kyaing, Dr Than Tun, Sao Htun Hmat Win, U Sai Aung Tun and Dr Thant Thaw Kaung. I thank them all, whether for their direct assistance in matters relating to Burma, for their ability to inspire me, or for simply providing encouragement. I thank my colleagues, past and present, at the National Gallery of Australia and staff at ANU who have also provided support during my thesis candidature, in particular: Ben Divall, Carol Cains, Christine Dixon, Jane Kinsman, Mark Henshaw, Lyn Conybeare, Margaret Brown and Chaitanya Sambrani. I give special mention to U Thaw Kaung, whose personal generosity and encouragement of those of us worldwide who express a keen interest in the study of Burma's rich cultural history, has ensured that I was able to achieve my own personal goals. There is no doubt that without his assistance and interest in my work, my ability to undertake the research required would have been severely compromised – thank you. -

U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019

Updated May 8, 2019 U.S. Relations with Burma: Key Issues in 2019 In 2018, the 115th Congress was generally critical of the Figure 1. Map of Burma (Myanmar) Trump Administration’s Burma policy, particularly its limited response to atrocities committed by the Burmese military, intensifying conflict with ethnic insurgencies, and rising concerns about political repression and civil rights. In December 2018, Congress passed the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-409), which prohibits funding for International Military Education and Training (IMET) and Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Program in Burma for fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Major Developments in Burma At the end of 2018, an estimated one million Rohingya, most of whom fled atrocities committed by Burma’s military (Tatmadaw) in late 2017, remained in refugee camps in Bangladesh, unable and unwilling to return to Burma’s Rakhine State given the current policies of the Burmese government. Also in 2018, fighting between Burma’s military and various ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) escalated in Kachin and Shan States, and spread into Chin, Karen (Kayin), and Rakhine States, while efforts to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire stalled. The Rohingya Crises Continue More than 700,000 Sunni Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in late 2017, seeking to escape Tatmadaw forces that destroyed almost 400 Rohingya villages, killed at least 6,700 Rohingya (according to human rights groups and Doctors Without Borders), and sexually assaulted hundreds of Rohingya women and girls. Repatriation under an October 2018 agreement between the two nations is stalled as the Burmese government is unable or unwilling to Source: CRS establish conditions that would allow the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable return of the Rohingya. -

Courts Manual

COURTS MANUAL GQCO-O 0COCO ฮ่3 ร:§o$§<8: L CD FOURTH EDITION 1999 Z c c s c n o o o s p : รํเะ 3j]o t' CO CO GO 0 3 gS ’ขนนร?•แ•.ช 15V SUPREME COURT TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1 PARA LEGAL PRACTIONERS AND PETITION WRITERS CHAPTER I- Advocates and Pleaders 1................. 1-11 CHAPTER แ- Petition Writers ............................... 12 PART n INSTRUCTIONS AND ORDERS RELATING TO BOTH CIVIL AND CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CHAPTER III- Adminstation and Conduct of Cases...... 13-48 CHAPTER IV- Evidence-Prisoners Act-Oaths Act ... 49-75 CHAPTER V- Court Fees and Stamps- Court Free Act-Stamps Act ..................... ......... 76-102 CHAPTER VI- Translation and Copies- Inspection ofRecords ........... .......................... 103-109 PART III CIVIL PROCEDURE CHAPTER VII- Procedure in Suits and Miscellaneous Proceedings ...................................... J10-182 CHAPTER VIII- Procedure in Execution ..................... 183-283 CHAPTER IX- Arrest and attachment before Judgment- Injunction .... ....................... ...... 284-288 CHAPTER X- Commissions .................................... 289-293 CHAPTER XI- Pauper Suits ................................... 294-297’ CHAPTER xn - Suits by or againt Goverment Attorney- General ................ ............... 289-299 CHAPTER Xffl- Appeal, Refemce and Revision ........ 300-309 CHAPTER XIV- Procedure under Special Enactments- 1. Specific Relief Act .................... 310-311 2. Tranfer of Property Act .......... 312-315 3. Myanmar Small Cause Courts Act.. 316-321 4. Land Acquisition Act .................... -

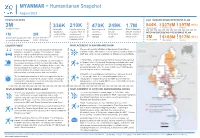

Myanmar – Humanitarian Snapshot (August 2021)

MYANMAR – Humanitarian Snapshot August 2021 PEOPLE IN NEED 2021 HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE PLAN 3M 336K 210K 470K 249K 1.7M 944K $276M $97M (35%) People targeted Requirements Received People in need Internally People internally Non-displaced Returnees and Other vulnerable displaced displaced due to stateless locally people, mostly in INTERIM EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN 1M 2M people at the clashes and persons in integrated urban and peri- start of 2021 Rakhine people urban areas people previously identified people identified insecurity since 2M $109M $17M (15%) February 2021 in conflict-affected areas since 1 February People targeted Requirements Received COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT IN KACHIN AND SHAN A total of 3 million people are targeted for humanitarian The overall security situation in Kachin and Shan states assistance across the country. This includes 1 million remains volatile, with various level of clashes reported between people in need in conflict-affected areas previously MAF and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) or among EAOs. identified and a further 2 million people since 1 February. Monsoon flash floods affected around 125,000 people in In Shan State, small-scale population movement was reported the regions and states of Kachin, Kayin, Mandalay, Mon, in Hsipaw, Muse, Kyethi and Mongkaing townships since mid- Rakhine, eastern Shan and Tanintharyi between late July July. In total, 24,950 people have been internally displaced and mid-August, according to local actors. Immediate across Shan State since the start of 2021; over 5,000 people needs of families affected or evacuated have been remain displaced in five townships. addressed by local aid workers and communities. In Kachin, no new displacement has been reported. -

Translated from the Hmannan Yazawin Dawgyl

Burmese I11vasions of Siam, Translated from the Hmannan Yazawin DawgyL ...T . Preface. 'l' he materials for the subject of this paper ·were ch awn almost entirely from the Hmn.nn a 11 Yazawin Dclwg·yi, a H istory of Burm a. in Burmese co1npil eLl by order of King Dagyict <l W of Burma i11 the ycn.r 1 101 B unnese era., A. D . 182!J . The nn t.ive work lms be en closely ac1l1erec1 to in tl1i · pnper, so nmch so that it may he co nsidered a free translat ion ( lr the original coveri 11g t he ~_J e r i o d treated of. A resume of the whole of '\vhat i · containea h re IYill lJe found in Sir A. rtlnu Phayre's llislory of Bul'lna . J n hi s l1 ist ory Sir Art hur Phayre has <Li so f ollowetl t lJ e Hmanua n Yazawin L irly closely, a nd he has utilized a1l th e in fonnat.ion IYh i.ch tl~e 1mt. ire work can offer t hat is worthy of a place in a history w rit t<~ n on European lines aml an::mgo cl it, at least tLS regards the p t·e-Alaungpric period, alm ost in the ordet· it is give n in the orig· in al. But what a, wide difference t here is between history written according to nnti ve ideas and that wr itten ou E nropoa.n principles, a. nd how far Si r Ar thur Phayre has sifted nud coudensed tl1e infon nat.ion co ntained in the original may be imagined when fi fteen pages, each containi ng t wenty eigltt lines of print in the nati1 e hist ory are wo rl.: ed into thirty one lines in Sir Arthur P ha:r re'::; . -

5) Bayinnaung in the Hanthawadi Shinbyumya Shin Ayedawbon Chronicle 2.Pmd

Bayinnaung in the Hanthawadi Hsinbyumya Shin Ayedawbon Chronicle by Thaw Kaung King Bayinnaung (AD 1551-1581) is known and respected in Myanmar as a great war- rior king of renown. Bayinnaung refers to himself in the only inscription that he left as “the Conqueror of the Ten Directions”.1 but this epithet is not found in the main Myanmar chronicles or in the Ayedawbon texts. Professor D. G. E. Hall of Rangoon University wrote that “Bayinnaung was a born leader of men. the greatest ever produced by Burma. ”2 There is a separate Ayedawbon historical chronicle devoted specifically to the campaigns and achievements of Bayinnaung entitled Hsinbyumya-shin Ayedawbon.3 Ayedawbon The term Ayedawbon means “a historical account of a royal campaign” 4 It also means a chronicle which records the campaigns and achivements of great kings like Rajadirit, Bayinnaung and Alaungphaya. The Ayedawbon is a Myanmar historical text which records : (1) How great men of prowess like Bayinnaung consolidated their power and became king. (2) How these kings retained their power by military campaigns, diplomacy, alliances and 1. For the full text of The Bell Inscription of King Bayinnaung see Report of the Superintendent, Archaeological Survey, Burma . 1953. Published 1955. p. 17-18. For the English translations by Dr. Than Tun and U Sein Myint see Myanmar Historical Research Journal. no. 8 (Dec. 2001) p. 16-20, 23-27. 2. D. G. E. Hall. Burma. 2nd ed. London : Hutchinson’s University Library, 1956. p.41. 3. The variant titles are Hsinbyushin Ayedawbon and Hanthawadi Ayedawbon. 4. Myanmar - English Dictionary. -

Shan State - Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit SHAN STATE - MYANMAR Mohnyin 96°40'E Sinbo 97°30'E 98°20'E 99°10'E 100°0'E 100°50'E 24°45'N 24°45'N Bhutan Dawthponeyan India China Bangladesh Myo Hla Banmauk KACHIN Vietnam Bamaw Laos Airport Bhamo Momauk Indaw Shwegu Lwegel Katha Mansi Thailand Maw Monekoe Hteik Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Konkyan Cambodia 24°0'N Muse 24°0'N Muse Manhlyoe (Manhero) Konkyan Namhkan Tigyaing Namhkan Kutkai Laukkaing Laukkaing Mabein Tarmoenye Takaung Kutkai Chinshwehaw CHINA Mabein Kunlong Namtit Hopang Manton Kunlong Hseni Manton Hseni Hopang Pan Lon 23°15'N 23°15'N Mongmit Namtu Lashio Namtu Mongmit Pangwaun Namhsan Lashio Airport Namhsan Mongmao Mongmao Lashio Thabeikkyin Mogoke Pangwaun Monglon Mongngawt Tangyan Man Kan Kyaukme Namphan Hsipaw Singu Kyaukme Narphan Mongyai Tangyan 22°30'N 22°30'N Mongyai Pangsang Wetlet Nawnghkio Wein Nawnghkio Madaya Hsipaw Pangsang Mongpauk Mandalay CityPyinoolwin Matman Mandalay Anisakan Mongyang Chanmyathazi Ai Airport Kyethi Monghsu Sagaing Kyethi Matman Mongyang Myitnge Tada-U SHAN Monghsu Mongkhet 21°45'N MANDALAY Mongkaing Mongsan 21°45'N Sintgaing Mongkhet Mongla (Hmonesan) Mandalay Mongnawng Intaw international A Kyaukse Mongkaung Mongla Lawksawk Myittha Mongyawng Mongping Tontar Mongyu Kar Li Kunhing Kengtung Laihka Ywangan Lawksawk Kentung Laihka Kunhing Airport Mongyawng Ywangan Mongping Wundwin Kho Lam Pindaya Hopong Pinlon 21°0'N Pindaya 21°0'N Loilen Monghpyak Loilen Nansang Meiktila Taunggyi Monghpyak Thazi Kenglat Nansang Nansang Airport Heho Taunggyi Airport Ayetharyar -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38.