Fairness Doctrine: Tracing the Decline of Positive Freedoms in American Policy Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title: the Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher's Guide of 20Fh Century Physics

REPORT NSF GRANT #PHY-98143318 Title: The Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher’s Guide of 20fhCentury Physics DOE Patent Clearance Granted December 26,2000 Principal Investigator, Brian Schwartz, The American Physical Society 1 Physics Ellipse College Park, MD 20740 301-209-3223 [email protected] BACKGROUND The American Physi a1 Society s part of its centennial celebration in March of 1999 decided to develop a timeline wall chart on the history of 20thcentury physics. This resulted in eleven consecutive posters, which when mounted side by side, create a %foot mural. The timeline exhibits and describes the millstones of physics in images and words. The timeline functions as a chronology, a work of art, a permanent open textbook, and a gigantic photo album covering a hundred years in the life of the community of physicists and the existence of the American Physical Society . Each of the eleven posters begins with a brief essay that places a major scientific achievement of the decade in its historical context. Large portraits of the essays’ subjects include youthful photographs of Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Richard Feynman among others, to help put a face on science. Below the essays, a total of over 130 individual discoveries and inventions, explained in dated text boxes with accompanying images, form the backbone of the timeline. For ease of comprehension, this wealth of material is organized into five color- coded story lines the stretch horizontally across the hundred years of the 20th century. The five story lines are: Cosmic Scale, relate the story of astrophysics and cosmology; Human Scale, refers to the physics of the more familiar distances from the global to the microscopic; Atomic Scale, focuses on the submicroscopic This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. -

University of Minnesota

THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Announces Its ;Uafclt eommellcemellt 1961 NORTHROP MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 16 AT EIGHT-THIRTY O'CLOCK Univcrsitp uf Minncsuta THE BOARD OF REGENTS Dr. O. Meredith Wilson, President Mr. Laurence R. Lunden, Secretary Mr. Clinton T. Johnson, Treasurer Mr. Sterling B. Garrison, Assistant Sccretary The Honorable Ray J. Quinlivan, St. Cloud First Vice President and Chairman The Honorable Charles W. Mayo, M.D., Rochester Second Vice President The Honorable James F. Bell, Minneapolis The Honorable Edward B. Cosgrove, Le Sueur The Honorable Daniel C. Gainey, Owatonna The Honorable Richard 1. Griggs, Duluth The Honorable Robert E. Hess, White Bear Lake The Honorable Marjorie J. Howard (Mrs. C. Edward), Excelsior The Honorable A. I. Johnson, Benson The Honorable Lester A. Malkerson, Minneapolis The Honorable A. J. Olson, Renville The Honorable Herman F. Skyberg, Fisher As a courtesy to those attending functions, and out of respect for the character of the building, be it resolved by the Board of Regents that there be printed in the programs of all functions held in Cyrus Northrop Memorial Auditorium a request that smoking be confined to the outer lobby on the main floor, to the gallery lobbies, and to the lounge rooms, and that members of the audience be not allowed to use cameras in the Auditorium. r/tis Js VOUf UnivcfsilU CHARTERED in February, 1851, by the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Minnesota, the University of Minnesota this year celebrated its one hundred and tenth birthday. As from its very beginning, the University is dedicated to the task of training the youth of today, the citizens of tomorrow. -

Congressional Record, Children and Youth, 1971, Part 5

S 16190 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE • October 12, 1971 Access: As to the first of them-the indi reconcile their theory to the facts. It is not United states. This translates into a con-' vidual's right to speak: TV time set aside this Administration that 18 pushing legal sumption rate of 1,408 million barrels a for sale should be available on a first-come, and regulatory controls on television, in order first-served basis at nondiscriminSitory to gain an active role in determining con day-enough oil to fill 62,000 railroad rates-but there must be no rate regulation. tent.. It is not th18 Adminlstration that 18 tank cars making a train 500 miles long. The individual would have a right to speak urging an extension of the Fairness Doctrine These statistics should be viewed in on any matter, whether it's to sell razor into the details of television news--or into terms of the impact of petroleum prod blades or urge an end to the war. The the print media. ucts on our daily lives. In this connection, licensee should not be held responsible for There is a world of difference between the I should mention that crude oil supplied the content of ads, beyond the need to guard professional responslblllty of a free press and agalnst lllegal material. Deceptive product the legal responslbUlty of a regulated press. 43.2 percent of all domestic energy needs ads should be controlled at the source by the This is the same difference between the in 1969. More than 60 percent of this Federal Trade Commission. -

Middleboro Gazette Index: 1940 - 1944

Middleboro Gazette Index: 1940 - 1944 A Accidents (continued) Ralph Howes' ankle broken during rush for gas at Standish station, A. Asia Dry Goods Store 07/24/1942:4 Grand opening, 133 Center St (ad), 01/05/1940:8 Five-year-old Gerald Trinque dragged 75 feet by Anthony Gilli's auto, Abatti, "Bozo" 08/28/1942:1 Member of 1940 Rambler baseball team (p), 10/04/1940:1 Arthur Angell injured by falling tree top, 01/15/1943:3 Abbott, Samuel L., Jr. Gerard Richmond falls on pitchfork while playing, 01/15/1943:6 New principal of School Street School, 08/25/1944:4 James William Thayer accidentally swallows a pin, 01/29/1943:7 Abele, Mannert Judith Caswell gets arm caught in wringer washer, 04/02/1943:4 Awarded Navy Cross for action against Japanese, 05/14/1943:1 Maurice Washburn loses three fingers to saw, 04/02/1943:7 Abele, Mannert L. Alfred Crowther fractures finger while repairing auto, 06/25/1943:3 Commander of submarine Grunion presumed lost, 10/09/1942:1 Arsene Berube treated for compound fracture of right arm, 06/25/1943:3 New destroyer named for commander lost in submarine, 04/21/1944:1 Jean Shores thrown off hayrack, dragged by pony, 07/02/1943:1 Abelson, Mrs Joseph Truesdale’s Jersey cow plunges into well, breaks neck, 10/08/1943:1 Husband finds wife dead on kitchen floor, 08/15/1941:4 Selectmen discuss role of dog who allegedly frighten cow, 10/15/1943:1 Abercrombie, A.V. David Noyer breaks arm in jump from steps, 01/28/1944:2 Daughter born, 03/08/1940:3, 4 Carl Carlson buried by avalanche of sand, 04/28/1944:1 Pastor resigns from Rock Village Church, 08/02/1940:1 Four-year-old Shirley Rea falls into river, carried through flume, Takes up duties in Woburn, 09/06/1940:6 05/19/1944:1 Resides in Woburn, 11/29/1940:6 Mrs Charles Weston suffers crushed finger working in yard, Son born, 03/20/1942:4 12/08/1944:10 Accepts call to Congregational church in Providence, 12/25/1942:5 Young boy knocked unconscious by falling ice, 12/22/1944:8 Abercrombie, Lois Ann Acconsia, Peter S. -

'Er State Church Unit Aids Andover Racial Fight

....■' '4 ' J , . V-.- ^.\LX AU ---- (--4- T.: . i ,\- TUESDAY, OCTOBER S8, 1968 / PAGE FOURTEEN ATerase D*fly Net Pren Ron The Weather iianrlf^at^r lEwnteg Forecast of IJ, 8. Weather ftireau 5 : For lbs Wssk Baded Oetoher 28, 196$ 8t, faihim to a m**®* d e a r and oool tonight. Low 30 There will be no admission 12th Circuit able distmoe apart, $20; Ray to- 36 with some 29s In normally charge for tonight’s Halloween mond W. Smith, B4, -of 10 FREE DELIVERY 13,876 cooler sections. 'Fhursdi^ most About Town party of the WA’TES that will ChuTOh St., speeding, $26; ly sunny, breezy and oool, Mgh Gourt Gases seph Steiner, 64, Marlborou^V 9 A.M . to 9 P.M. Msubsr of Oa Audit 80 to 66. be held at the Italiah American Bnrsau of Ordolatlon Holy Family Retreat. dub, EldrWge St., at 7. intoxication, $10; Frank W. Mancheater~—A City o f Village Charm Ijogan, 10, Wapptng, causing I^aague, Manchester Chapter, MANOHESTER 8B»8I0N haa canceled its meeting for St. John’s PoUsh National unnecoasary noise with a m o- ARTHUR DRUB Whiter J. ’Topolsld, 26, Bast tor vehicle, $15; Janet C. Bieu tonight Catholic Church haa announced Hartford, yesterday pleaded not MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 30, 1963 (Classified Advertising on Pagti 22) PRICE SEVEN CENTS the schedule for All Saints Day, of 96 Charter Oak St., in toxl«- VOL. LXXXra, NO. 86 (TWENTY-FOUR PAGES—TWO SECTIONS) guilty to a rape charge and Uon. $10; Barry W. Cowles, 2^ A n a congTcgO’tlo’w •>* Jeho Friday, when Mass will be held the case was continued until vah’s Witnesses will attend a at 8:30 ajn. -

Remarks Commissioner Michael J. Copps Everett Parker Ethics in Communications Lecture Washington, Dc September 24, 2002

REMARKS COMMISSIONER MICHAEL J. COPPS EVERETT PARKER ETHICS IN COMMUNICATIONS LECTURE WASHINGTON, DC SEPTEMBER 24, 2002 I am truly and deeply honored to deliver the Everett C. Parker Ethics in Communications Lecture this year. I feel twice humbled. First because Dr. Parker did his communications ethics out on the front lines, battling for civil rights back in the difficult and dangerous days of the 1950s and 1960s, when many of us were only beginning to awaken to the horrid injustice of racial intolerance and to the moral justice of America’s civil rights movement. A lecturer can get by with talking the talk, but Dr. Parker was walking the walk -- and what a daunting walk it must have been -- so many decades ago. The second humbling challenge is that we meet at something of another ethical crossroads this year, and we feel the need for reflection and correction in numerous spheres of our nation’s life -- including some that involve very directly our communications industries and how their evolution will affect each of our lives. Dr. Parker was in the vanguard leading us out of those earlier and doubtless more dramatic challenges, but I submit, first, that the current challenges are serious onto themselves and, secondly, that the same ethics and vision that he brought to those earlier front lines are equally imperative today. Most of us assembled here today are familiar with what is arguably Dr. Parker’s most famous crusade -- the WLBT case. We know how, in March of 1964, he and the United Church of Christ went to Jackson, Mississippi to look at the media there and how they found that although African-Americans comprised 45 percent of the TV audience, their concerns were completely ignored by the local stations. -

Media 2070: an Invitation to Dream up Media Reparations

An Invitation to Dream Up Media Reparations AN INVITATION TO DREAM UP MEDIA REPARATIONS Collaborators: Joseph Torres Alicia Bell Collette Watson Tauhid Chappell Diamond Hardiman Christina Pierce a project of Free Press 2 WWW.MEDIA2070.ORG CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 9 I. A Day at the Beach 13 II. Media 2070: An Invitation to Dream 18 III. Modern Calls for Reparations for Slavery 19 IV. The Case for Media Reparations 24 V. How the Media Profited from and Participated in Slavery 26 VI. The Power of Acknowledging and Apologizing 29 VII. Government Moves to Suppress Black Journalism 40 VIII. Black People Fight to Tell Our Stories in the Jim Crow Era 43 IX. Media Are the Instruments of a White Power Structure 50 X. The Struggle to Integrate Media 52 XI. How Public Policy Has Entrenched Anti-Blackness in the Media 56 XII. White Media Power and the Trump Feeding Frenzy 58 XIII. Media Racism from the Newsroom to the Boardroom 62 XIV. 2020: A Global Reckoning on Race 66 X V. Upending White Supremacy in Newsrooms 70 XVI. Are Newsrooms Ready to Make Things Right? 77 XVII. The Struggles of Black Media Resistance 80 XVIII. Black Activists Confront Online Gatekeepers 83 XIX. Media Reparations Are Necessary to Our Nation’s Future 90 XX. Making Media Reparations Real 95 Epilogue 97 About Team Media 2070 98 Definitions 99 #MEDIA2070 3 TRIGGER WARNING There are numerous stories in this essay that explore the harms the news media have inflicted on the Black community. While these stories may be difficult or painful to read, they are not widely known, and they need to be. -

Tracking the Columbia Summer Program Graduates, 1968-1974

Training for Diversity in Journalism: Tracking the Columbia Summer Program Graduates, 1968 – 1974 A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Communication East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Professional Communication by Mary Alice Basconi May 2006 Dr. John M. King, Chair Dr. Jack Mooney Dr. Ardis Nelson Keywords: Minorities, diversity, retention, journalism training, journalism history, journalism education ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work is dedicated to Ed Basconi, for immeasurable kindness and patience, and to my parents, Alicia Serafica Woodhams and Richard L. Woodhams, for showing the way. Special appreciation goes to Dr. John M. King for chairing the thesis committee, for believing in this endeavor, and for guidance through the mechanics of SPSS. Dr. Jack Mooney provided the spark for this project by challenging students to tell stories that make up journalism history. He and Dr. Ardis Nelson offered insight during the research and enlisted me in the bilingual newspaper project at ETSU. The School of Graduate Studies was generous in providing guidance and travel assistance, and Kelly Hensley at the Sherrod Library was helpful in locating research materials. Personal thanks also are due to Dr. Charles Roberts, Dr. Norma Wilson, Dr. Murvin H. Perry, Dr. Cecilia McIntosh, Dr. Andrea Clements, Dr. Rosalind Gann, and Janine Richardson. Several persons clarified information and guided me to the records: Ruth Friendly of the Fred Friendly Seminars, who provided access to her husband’s papers; Alexandra Bernet of the Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Anthony Malony of the Ford Foundation, Dr. -

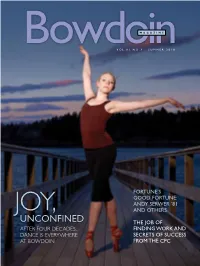

Unconfined the Job of After Four Decades, Finding Work and Dance Is Everywhere Secrets of Success at BOWDOIN from the CPC SUMMER 2010 CONTENTS Bowdoinm a G a Z I N E

M a g a z i n e BowdoinV o l . 8 1 N o . 3 S u m m e r 2 0 1 0 ForTuNe’S GoodForTuNe: ANdySerwer’81 Joy, ANdoTherS uNcoNFiNed TheJoBoF After four decAdes, FiNding Work and dAnce is everywhere SecreTSoFSucceSS At BOWDOIN From thecPc suMMer 2010 contents BowdoinM a g a z i n e 16 LetJoybe Unconfined PhotogrAPhs By BoB hAndelMAn In honor of four decades of dance at Bowdoin, and in recognition of the ways in which the dance program is inclusive and expansive, we decided to take the dancers out of their typical performance spaces and photograph them appearing in campus spots both familiar and unexpected. 30 Fortune’sGoodFortune By doug Boxer-cook • PhotogrAPhs By kArsten MorAn Director of News and Media Relations Doug Boxer-Cook visits with Fortune Magazine editor Andy Serwer ’81. In addition to Serwer, the global business publication has the good fortune to have other Bowdoin graduates writing and working there. 42 TheJobofFinding Work By iAn Aldrich • PhotogrAPhs By deAn ABrAMson Bowdoin students have graduated into a tough economy for the last couple of years. Thankfully, director Tim Diehl and others at Bowdoin’s Career Planning Center, with valued assistance from “the Bowdoin network,” are ready to help. dePArTmeNTS Mailbox 2 Bookshelf 6 Bowdoinsider 8 Alumnotes 52 class news 53 weddings 79 obituaries 86 | l e t t e r | Bowdoin From theediTor MAgAZine volume 81, number 3 the gifts of summer summer, 2010 aine summers are full of messages to us. -

Entire Issue

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 158 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, APRIL 23, 2012 No. 58 House of Representatives The House met at 11 a.m. and was PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES, called to order by the Speaker pro tem- HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, The SPEAKER pro tempore. The Washington, DC, April 19, 2012. pore (Mr. CULBERSON). Chair will lead the House in the Pledge Hon. JOHN A. BOEHNER, f of Allegiance. Speaker, House of Representatives, Washington, DC. DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER The SPEAKER pro tempore led the DEAR MR. SPEAKER: This is to notify you PRO TEMPORE Pledge of Allegiance as follows: formally pursuant to Rule VIII of the Rules The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the of the House of Representatives that I have fore the House the following commu- United States of America, and to the Repub- been served with a subpoena, issued by the nication from the Speaker: lic for which it stands, one nation under God, 362nd Judicial District Court in Denton, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. Texas, to testify in a criminal case. WASHINGTON, DC, After consultation with the Office of Gen- April 23, 2012. eral Counsel, I have determined that compli- I hereby appoint the Honorable JOHN f ance with the subpoena is consistent with ABNEY CULBERSON to act as Speaker pro tem- pore on this day. the precedents and privileges of the House. -

Abbreviations Used in Notes

Notes Abbreviations Used in Notes APRP A. Philip Randolph Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC ARC Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA BCP Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor Papers, Department of Archives and Manuscripts, Bir- mingham Public Library, Birmingham, AL BMP Burke Marshall Papers, John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, MA BPL Department of Archives and Manuscripts, Birmingham Public Library, Birmingham, AL BRP Bayard Rustin Papers (microfilm) BSCPP Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC CCHP Clarie Collins Harvey Papers, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA COREC Congress of Racial Equality Collection, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PA COREP Congress of Racial Equality Papers (microfilm) COREPA Congress of Racial Equality Papers, Addendum, 1944–1968 (microfilm) CUOHC Columbia University Oral History Collection, New York, NY FBI-FRI FBI Case Files, Freedom Rider Investigation, Department of Archives and Manuscripts, Birmingham Public Library, Birmingham, AL FORP Fellowship of Reconciliation Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, PA FUSC Fisk University Special Collections, Nashville, TN ICCR Interstate Commerce Commission Records, Record Group 134, U.S. National Archives II, College Park, MD JFKL John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, MA KMSP Kelly Miller Smith Papers, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN KPA Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers, the Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Atlanta, GA MLKP Martin Luther King, Jr., Papers, Mugar Library, Boston University, Boston, MA MSCP Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, MS NAACPP National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC NTP Norman Thomas Papers, New York Public Library, New York, NY RBOHC Ralph Bunche Oral History Collection, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard Uni- versity, Washington, DC Notes to Pages 1–4 589 RFKP Robert F. -

The Private Agreement and Citizen Participation in Broadcast Regulation. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 120P.; M.A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 079 784 cs 500 350 AUTHOR Fry, Carlton Ford' TITLE The Private Agreement and Citizen Participation in Broadcast Regulation. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 120p.; M.A. Thesis, Ohio State University EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Broadcast Industry; Broadcast Illevision; *Citizen Participation; *Commercial Television; Community Organizations; Court Litigation; *Legal Responsibility; *Programing (Broadcast); *Public Affairs Education; Public Television; Telecommunication IDENTIFIERS Broadcaster Licenses; *Federal Communicatiops Commission; Office of Communication (Federal) ABSTRACT The kind and extent of public access and control in broadcast commercial television is currently in a state of extreme flux. The history of public groups that exert pressure on television stations, management for changes in programing and policies ranges from small complaints to fully organized license challenges in the courts. However, most of the conflicts between broadcasters and public interest forces are settled privately--out of court. The effect of such private negotiation is not always in the interests of the whole public. Placation of one grievance rather than iasic improvement is sometimes the result..Solution tp this situation likely lies with the Federal Communications Commission. .(CH) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH EDUCATION L WELFAR:. NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED I.ROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIGN ORIGIN .TING IT POINTS Or viEN OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NPONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY THE PRIVATE AGREEMENT AND CITIZEN PARTICIPATION IN BROADCAST REGULATION A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCETHIS COPY.