Tracking the Columbia Summer Program Graduates, 1968-1974

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMPLAINT SUZANNE SCOTT, Individually, and JURY DEMAND

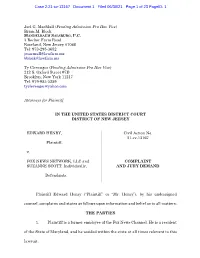

Case 2:21-cv-13167 Document 1 Filed 06/30/21 Page 1 of 23 PageID: 1 Joel G. MacMull (Pending Admission Pro Hac Vice) Brian M. Block MANDELBAUM SALSBURG, P.C. 3 Becker Farm Road Roseland, New Jersey 07068 Tel: 973-295-3652 [email protected] [email protected] Ty Clevenger (Pending Admission Pro Hac Vice) 212 S. Oxford Street #7D Brooklyn, New York 11217 Tel: 979-985-5289 [email protected] Attorneys for Plaintiff IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY EDWARD HENRY, Civil Action No. 21-cv-13167 Plaintiff, v. FOX NEWS NETWORK, LLC and COMPLAINT SUZANNE SCOTT, Individually, AND JURY DEMAND Defendants. Plaintiff Edward Henry (“Plaintiff” or “Mr. Henry”), by his undersigned counsel, complains and states as follows upon information and belief as to all matters: THE PARTIES 1. Plaintiff is a former employee of the Fox News Channel. He is a resident of the State of Maryland, and he resided within the state at all times relevant to this lawsuit. Case 2:21-cv-13167 Document 1 Filed 06/30/21 Page 2 of 23 PageID: 2 2. Defendant Suzanne Scott (“Ms. Scott”) is the Chief Executive Officer of the Fox News Channel and Fox Business Channel, both of which are owned by Fox News Network, LLC. She is a resident of the State of New Jersey, and she resided within the state at all times relevant to this lawsuit. 3. Fox News Network, LLC (“Fox News”) is a limited liability company with a business addressed located at 1211 Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10036. -

Title: the Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher's Guide of 20Fh Century Physics

REPORT NSF GRANT #PHY-98143318 Title: The Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher’s Guide of 20fhCentury Physics DOE Patent Clearance Granted December 26,2000 Principal Investigator, Brian Schwartz, The American Physical Society 1 Physics Ellipse College Park, MD 20740 301-209-3223 [email protected] BACKGROUND The American Physi a1 Society s part of its centennial celebration in March of 1999 decided to develop a timeline wall chart on the history of 20thcentury physics. This resulted in eleven consecutive posters, which when mounted side by side, create a %foot mural. The timeline exhibits and describes the millstones of physics in images and words. The timeline functions as a chronology, a work of art, a permanent open textbook, and a gigantic photo album covering a hundred years in the life of the community of physicists and the existence of the American Physical Society . Each of the eleven posters begins with a brief essay that places a major scientific achievement of the decade in its historical context. Large portraits of the essays’ subjects include youthful photographs of Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Richard Feynman among others, to help put a face on science. Below the essays, a total of over 130 individual discoveries and inventions, explained in dated text boxes with accompanying images, form the backbone of the timeline. For ease of comprehension, this wealth of material is organized into five color- coded story lines the stretch horizontally across the hundred years of the 20th century. The five story lines are: Cosmic Scale, relate the story of astrophysics and cosmology; Human Scale, refers to the physics of the more familiar distances from the global to the microscopic; Atomic Scale, focuses on the submicroscopic This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. -

Www. George Wbush.Com

Post Office Box 10648 Arlington, VA 2221 0 Phone. 703-647-2700 Fax: 703-647-2993 www. George WBush.com October 27,2004 , . a VIA FACSIMILE (202-219-3923) AND CERTIFIED MAIL == c3 F Federal Election Commission 999 E Street NW Washington, DC 20463 b ATTN: Office of General Counsel e r\, Re: MUR3525 Dear Federal Election Commission: On behalf of President George W. Bush and Vice President Richard B. Cheney as candidates for federal office, Karl Rove, David Herndon and Bush-Cheney ’04, Inc., this letter responds to the allegations contained in the complaint filed with the Federal Election Commission (the “Commission”) by Kerry-Edwards 2004, Inc. The Kerry Campaign’s complaint alleges that Bush-Cheney 2004 and fourteen other individuals and organizations violated the Federal Election Campaign Act of 197 1, as amended (2 U.S.C. $ 431 et seq.) (“the Act”). Specifically, the Kerry Campaign alleges that individuals and organizations named in the complaint illegally coordinated with one another to produce and air advertising about Senator. Kerry’s military service. 1 Considering that no entity by the name of Bush-Cheney 2004 appears to exist, 1’ Bush-Cheney ’04, Inc. (“Bush Campaign”) presumes that the Kerry Campaign mistakenly filed its complaint against a non-existent entity and actually intended to file against the Bush Campaign. Assuming that the foregoing presumption is correct; the Bush Campaign, on behalf of itself and President George W. Bush, Vice President Richard B. Cheney, Karl Rove, David Herndon (the “Parties”), responds as follows: Response to Allegations Against President George W. Bush, Vice President Richard B. -

University of Minnesota

THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Announces Its ;Uafclt eommellcemellt 1961 NORTHROP MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 16 AT EIGHT-THIRTY O'CLOCK Univcrsitp uf Minncsuta THE BOARD OF REGENTS Dr. O. Meredith Wilson, President Mr. Laurence R. Lunden, Secretary Mr. Clinton T. Johnson, Treasurer Mr. Sterling B. Garrison, Assistant Sccretary The Honorable Ray J. Quinlivan, St. Cloud First Vice President and Chairman The Honorable Charles W. Mayo, M.D., Rochester Second Vice President The Honorable James F. Bell, Minneapolis The Honorable Edward B. Cosgrove, Le Sueur The Honorable Daniel C. Gainey, Owatonna The Honorable Richard 1. Griggs, Duluth The Honorable Robert E. Hess, White Bear Lake The Honorable Marjorie J. Howard (Mrs. C. Edward), Excelsior The Honorable A. I. Johnson, Benson The Honorable Lester A. Malkerson, Minneapolis The Honorable A. J. Olson, Renville The Honorable Herman F. Skyberg, Fisher As a courtesy to those attending functions, and out of respect for the character of the building, be it resolved by the Board of Regents that there be printed in the programs of all functions held in Cyrus Northrop Memorial Auditorium a request that smoking be confined to the outer lobby on the main floor, to the gallery lobbies, and to the lounge rooms, and that members of the audience be not allowed to use cameras in the Auditorium. r/tis Js VOUf UnivcfsilU CHARTERED in February, 1851, by the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Minnesota, the University of Minnesota this year celebrated its one hundred and tenth birthday. As from its very beginning, the University is dedicated to the task of training the youth of today, the citizens of tomorrow. -

Completeandleft Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F

MEN WOMEN 1. FA Frankie Avalon=Singer, actor=18,169=39 Fiona Apple=Singer-songwriter, musician=49,834=26 Fred Astaire=Dancer, actor=30,877=25 Faune A.+Chambers=American actress=7,433=137 Ferman Akgül=Musician=2,512=194 Farrah Abraham=American, Reality TV=15,972=77 Flex Alexander=Actor, dancer, Freema Agyeman=English actress=35,934=36 comedian=2,401=201 Filiz Ahmet=Turkish, Actress=68,355=18 Freddy Adu=Footballer=10,606=74 Filiz Akin=Turkish, Actress=2,064=265 Frank Agnello=American, TV Faria Alam=Football Association secretary=11,226=108 Personality=3,111=165 Flávia Alessandra=Brazilian, Actress=16,503=74 Faiz Ahmad=Afghan communist leader=3,510=150 Fauzia Ali=British, Homemaker=17,028=72 Fu'ad Aït+Aattou=French actor=8,799=87 Filiz Alpgezmen=Writer=2,276=251 Frank Aletter=Actor=1,210=289 Frances Anderson=American, Actress=1,818=279 Francis Alexander+Shields= =1,653=246 Fernanda Andrade=Brazilian, Actress=5,654=166 Fernando Alonso=Spanish Formula One Fernanda Andrande= =1,680=292 driver.=63,949=10 France Anglade=French, Actress=2,977=227 Federico Amador=Argentinean, Actor=14,526=48 Francesca Annis=Actress=28,385=45 Fabrizio Ambroso= =2,936=175 Fanny Ardant=French actress=87,411=13 Franco Amurri=Italian, Writer=2,144=209 Firoozeh Athari=Iranian=1,617=298 Fedor Andreev=Figure skater=3,368=159 ………… Facundo Arana=Argentinean, Actor=59,952=11 Frickin' A Francesco Arca=Italian, Model=2,917=177 Fred Armisen=Actor=11,503=68 Frank ,Abagnale ,Criminal ,Catch Me If You Can François Arnaud=French Canadian actor=9,058=86 Ferhat ,Abbas ,Head of State ,President of Algeria, 1962-63 Fábio Assunção=Brazilian actor=6,802=99 Floyd ,Abrams ,Attorney ,First Amendment lawyer COMPLETEandLEFT Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F. -

A Comparative Study of the Educational Needs Of

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE EDUCATIONAL NEEDS OF TELEVISION REPORTERS AS PERCEIVED BY TELEVISION NEWS DIRECTORS AND BROADCAST JOURNALISM EDUCATORS by JACK PAUL MATNEY, B.J., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN EDUCATION Submitte(j to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Approve(J December, 1989 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to (dedicate this dissertation to my wife, Sandra, and to my daughters Marci, Malee and Makell whose constant love, support and sacrifice made this study possible, and to my parents Carl and Frances Matney, without whose continual support and encouragement my graduate studies would not have been possible- I offer my love and appreciation to my wife, children and parents for their love, interest and support. I am deeply indebted to many who have contributed to this study. I wish to thank Dr. Dayton Roberts, Chairman of my committee, for his guidance and support. I also extend my appreciation to Dr. Joe Cornett, Dr. Dennis Harp, Dr. Jerry Hudson, and Dr. Mike Mezack for their direction. For their interest, expertise and guidance I am grateful to Bill Semmelbeck, Dr. Phil Gensler, Dr. Stan Adelman, Mark Hanna and Mindy Briggs. Dr. Gene Byrd, Vice President and Dean of Instruction at Amarillo College, has provided continual support throughout my graduate studies. For his understanding and consideration, I am especially thankful. I also thank Pat Knight, a friend and colleague, for her encouragement and assistance. No study such as this is possible without the encouragement of friends. I wish to extend special ii appreciation to Robert Boyd, Brenda Turner and Susie Peery for their friendship and assistance. -

1973 NGA Annual Meeting

Proceedings OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE 1973 SIXTY-FIFTH ANNUAL MEETING DEL WEBB'S SAHARA TAHOE. LAKE TAHOE, NEVADA JUNE 3-61973 THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40511 Published by THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40511 CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters . vi Other Committees of the Conference vii Governors and Guest Speakers in Attendance ix Program of the Annual Meeting . xi Monday Session, June 4 Welcoming Remarks-Governor Mike O'Callaghan 2 Address of the Chairman-Governor Marvin Mandel 2 Adoption of Rules of Procedure 4 "Meet the Governors" . 5 David S. Broder Lawrence E. Spivak Elie Abel James J. Kilpatrick Tuesday Session, June 5 "Developing Energy Policy: State, Regional and National" 46 Remarks of Frank Ikard . 46 Remarks of S. David Freeman 52 Remarks of Governor Tom McCall, Chairman, Western Governors' Conference 58 Remarks of Governor Thomas J. Meskill, Chairman, New England Governors' Conference . 59 Remarks of Governor Robert D. Ray, Chairman, Midwestern Governors' Conference 61 Remarks of Governor Milton J. Shapp, Vice-Chairman, Mid-Atlantic Governors' Conference . 61 Remarks of Governor George C. Wallace, Chairman, Southern Governors' Conference 63 Statement by the Committee on Natural Resources and Environmental Management, presented by Governor Stanley K. Hathaway 65 Discussion by the Governors . 67 "Education Finance: Challenge to the States" 81 Remarks of John E. Coons . 81 Remarks of Governor Wendell R. Anderson 85 Remarks of Governor Tom McCall 87 Remarks of Governor William G. Milliken 88 iii Remarks of Governor Calvin L. Rampton 89 Discussion by the Governors . 91 "New Directions in Welfare and Social Services" 97 Remarks by Frank Carlucci 97 Discussion by the Governors . -

Congressional Record, Children and Youth, 1971, Part 5

S 16190 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE • October 12, 1971 Access: As to the first of them-the indi reconcile their theory to the facts. It is not United states. This translates into a con-' vidual's right to speak: TV time set aside this Administration that 18 pushing legal sumption rate of 1,408 million barrels a for sale should be available on a first-come, and regulatory controls on television, in order first-served basis at nondiscriminSitory to gain an active role in determining con day-enough oil to fill 62,000 railroad rates-but there must be no rate regulation. tent.. It is not th18 Adminlstration that 18 tank cars making a train 500 miles long. The individual would have a right to speak urging an extension of the Fairness Doctrine These statistics should be viewed in on any matter, whether it's to sell razor into the details of television news--or into terms of the impact of petroleum prod blades or urge an end to the war. The the print media. ucts on our daily lives. In this connection, licensee should not be held responsible for There is a world of difference between the I should mention that crude oil supplied the content of ads, beyond the need to guard professional responslblllty of a free press and agalnst lllegal material. Deceptive product the legal responslbUlty of a regulated press. 43.2 percent of all domestic energy needs ads should be controlled at the source by the This is the same difference between the in 1969. More than 60 percent of this Federal Trade Commission. -

Reese, Stephen D., the Structure of News Sources on Television: A

Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources -

Hawaiian Day July 7

Full Moon Day July 5 According toThe Old Farmer's Almanac, July's full moon is known as the Full Buck Moon. That's because it's normally the month when a buck deer gets the beginnings of his new antlers. It's also known as the Thunder Moon (because thunderstorms are common at this time) and the Full Hay Moon. Do you know the Names of All the Full Moons? How many "moon" phrases you name? The moon phase is the shape of the directly sunlit portion of the Moon as viewed from Earth. The phases gradually change over the period of a synodic month, as the orbital positions of the Moon around Earth and of Earth around the Sun Shift. July 6 Fried Chicken Day Fried chicken has a long and interesting history—Here are a few facts: Fried Chicken Was Invented by the Scottish. Before WWII, It Was a Special Occasion Dish. Not all Chickens are Suitable for Frying. There are Three Primary Frying Methods— deep-frying ,pressure- frying (or “broasting”), cast-iron skillet . The Pressure Fryer Was the Secret to KFC’s Success. Hawaiian Day July 7 The Hawaiian Islands Kingdom was annexed by the United States on this day in 1898. Hawaii was once an independent kingdom. (1810 - 1893) The flag was designed at the request of King Kamehameha I. It has eight stripes of white, red and blue that represent the eight main islands. The flag of Great Britain is emblazoned in the upper left corner to honor Hawaii's friendship with the British. -

Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2018 Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the American Politics Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Political Theory Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Hopper, Hannah, "Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3402. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3402 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Media and Communication East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Brand and Media Strategy _____________________ by Hannah Hopper May 2018 _____________________ Dr. Susan E. Waters, Chair Dr. Melanie Richards Dr. Phyllis Thompson Keywords: Political Journalist, Twitter, Agenda Setting, Framing, Gatekeeping, Feminist Political Theory, Political Polarization, Presidential Debate, Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump ABSTRACT Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate by Hannah Hopper Past research shows that journalists are gatekeepers to information the public seeks. -

Oral History Interview with Sharon Huntley Kahn, July 10, 2018

Archives and Special Collections Mansfield Library, University of Montana Missoula MT 59812-9936 Email: [email protected] Telephone: (406) 243-2053 This transcript represents the nearly verbatim record of an unrehearsed interview. Please bear in mind that you are reading the spoken word rather than the written word. Oral History Number: 463-001 Interviewee: Sharon Huntley Kahn Interviewer: Donna McCrea Date of Interview: July 10, 2018 Donna McCrea: This is Donna McCrea, Head of Archives and Special Collections at the University of Montana. Today is July 10th of 2018. Today I'm interviewing Sharon Huntley Kahn about her father Chet Huntley. I'll note that the focus of the interview will really be on things that you know about Chet Huntley that other people would maybe not have known: things that have not been made public already or don't appear in many of the biographical materials and articles about him. Also, I'm hoping that you'll share some stories that you have about him and his life. So I'm going to begin by saying I know that you grew up in Los Angeles. Can you maybe start there and talk about your memories about your father and your time in L.A.? Sharon Kahn: Yes, Donna. Before we begin, I just want to say how nice it is to work with you. From the beginning our first phone conversations, I think at least a year and a half ago, you've always been so welcoming and interested, and it's wonderful to be here and I'm really happy to share inside stories with you.