The Resurrection of Joyce Reason Matthew Reason Archive, Empathy, Memory: the Resurrection of Joyce Reason — Matthew Reason

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Complete Issue

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY (incorporating the Congregational History Society, founded in 1899, and the Presbyterian Historical Society of England, founded in 1913). EDITOR: Dr. CLYDE BINFIELD, M.A. Volume 4 No. 3 October 1988 CONTENTS Editorial 169 Confessing the Faith in English Congregationalism by Alan P.F.Sell, M.A., B.D., Ph.D., F.S.A. 170 Zion, Hulme, Manchester: Portrait of a Church by Ian Sellers, M.A. M.Litt., Ph.D. 216 Reviews by Lilian Wildman, Mark Haydock, Edwin Welch 231 EDITORIAL This is the third successive edition ofthelournal to benefit from the generosity of an outside body. This time the debt is to the World Alliance of Reformed Churches. Professor Sell's paper was originally prepared for an Alliance consultation. Its contents are firmly in the traditions of the Journal and its Presbyterian and Congregational predecessors. Its style reaches back particularly to that of the Congregational Historical Society's earlier Transactions. As a summation of the confessional development of the larger part of the English tradition of what is now the United Reformed Church, Professor Sell's essay is self-evidently important. Is it too much to hope that it will be required reading for each student in a United Reformed college and each minister in a United Reformed pastorate, as well as for this Journal's constituency which goes beyond United Reformed boundaries? Dr. Sellers's paper is in suggestive counterpoint to Professor Sell's. It was delivered in May 1988 at Southport as the society's Assembly Lecture. To join these hardened contributors we welcome as reviewers Mrs. -

This Is a Print Edition, Issued in 1998. to Ensure That You Are Reviewing Current Information, See the Online Version, Updated in the SOAS Archives Catalogue

This is a print edition, issued in 1998. To ensure that you are reviewing current information, see the online version, updated in the SOAS Archives Catalogue. http://archives.soas.ac.uk/CalmView/ Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=PP+MS+63 PAPERS OF J. T. HARDYMAN PP MS 63 July 1998 J. T. HARDYMAN PP MS 63 Introduction James Trenchard Hardyman was born in Madagascar in 1918, son of missionaries A. V. Hardyman and Laura Hardyman (nee Stubbs). The Hardymans married in 1916 and worked in Madagascar for the London Missionary Society from that year until 1938 and from 1944 to 1950. As a child J. T. Hardyman was sent to England to be educated under the guardianship of the Rev. and Mrs J. H. Haile. Hardyman became a missionary with the London Missionary Society in 1945, in the same year that he married Marjorie Tucker. From 1946 until 1974 the Hardymans lived in Madagascar at Imerimandroso. As well as his missionary work within the Antsihanaka area, Hardyman became the Principal of the Imerimandroso College training Malagasy pastors. Following his return to England, Hardyman worked as Honorary Archivist of the CWM at Livingstone House (1974-91) and for the CBMS (1976-1988). In this capacity he oversaw the deposit of both archives at SOAS. From 1974-83 he also worked for the Overseas Book Service of Feed the Minds. J. T. Hardyman died on 1 October 1995. At the age of eleven, Hardyman was given by Haile a second-hand copy of a book on Madagascar published anonymously by 'a resident' in the 1840s, and this began his collection of published and unpublished material relating to Madagascar; a collection which was to become possibly the most comprehensive private collection in the world. -

Welcome: Tapra @ 10 Getting to Royal Holloway and Local Taxis Wifi Eating and Drinking Keynote Speakers Performance Practice

3 Welcome: TaPRA @ 10 5 Getting to Royal Holloway and local taxis 6 Wifi 6 Eating and Drinking 10 Keynote Speakers 12 Performance 14 Practice Gallery 19 Schedule 43 Abstracts and Biography 203 Working Group Conveners 204 Maps and Rooms 1 2 Welcome: TaPRA @ 10 This short prologue is by way of a welcome to the 10th anniversary conference for TaPRA at Royal Holloway. It is fitting that we should be here at the end of our ninth year, as two of the founder members of the executive, David Bradby and Jacky Bratton spent the larger part of their academic careers in the department and Royal Holloway has played an important role more generally in the work of TaPRA over the years, with staff convening working groups and a large contingent at every conference. TaPRA began at the University of Manchester in 2005. The organization, which had many different names in its first sixth months, came out of both a desire to celebrate our research and a frustration at the divisive nature of the (then) RAE. With a growing impatience at the lack of a national association for specifically UK-based theatre and performance research, the idea was to form an organization that could be membership based and conference lead, could be used by emerging scholars and more established scholars alike, as a place to try out their ideas. The original founders, David Bradby, Jacky Bratton, Maggie B.Gale, Viv Gardner and Baz Kershaw were joined by Maria Delgado, Brian Singleton, Kate Newey, Andy Lavender, Sophie Nield and Paul Allain – as the founding executive. -

Tapra @ 10 Getting to Royal Holloway and Local Taxis Wifi Eating

3 Welcome: TaPRA @ 10 5 Getting to Royal Holloway and local taxis 6 Wifi 6 Eating and Drinking 10 Keynote Speakers 12 Performance 14 Practice Gallery 19 Schedule 43 Abstracts and Biography 203 Working Group Conveners 204 Maps and Rooms 1 2 Welcome: TaPRA @ 10 This short prologue is by way of a welcome to the 10th anniversary conference for TaPRA at Royal Holloway. It is fitting that we should be here at the end of our ninth year, as two of the founder members of the executive, David Bradby and Jacky Bratton spent the larger part of their academic careers in the department and Royal Holloway has played an important role more generally in the work of TaPRA over the years, with staff convening working groups and a large contingent at every conference. TaPRA began at the University of Manchester in 2005. The organization, which had many different names in its first sixth months, came out of both a desire to celebrate our research and a frustration at the divisive nature of the (then) RAE. With a growing impatience at the lack of a national association for specifically UK-based theatre and performance research, the idea was to form an organization that could be membership based and conference lead, could be used by emerging scholars and more established scholars alike, as a place to try out their ideas. The original founders, David Bradby, Jacky Bratton, Maggie B.Gale, Viv Gardner and Baz Kershaw were joined by Maria Delgado, Brian Singleton, Kate Newey, Andy Lavender, Sophie Nield and Paul Allain – as the founding executive. -

Dorey Richmond, Jules and Richmond, David (2016) Inside the Experience of Making Personal Archive #1 [A Work in Progress]: the Art of Inquiry

Dorey Richmond, Jules and Richmond, David (2016) Inside the Experience of Making Personal Archive #1 [A Work in Progress]: The art of Inquiry. Memory Connection, 2 (1). pp. 112-126. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/1641/ The version presented here may differ from the published version or version of record. If you intend to cite from the work you are advised to consult the publisher's version: http://memoryconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/The-Cultures-of-Memory.pdf Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] MEMORY CONNECTION Volume 2, Number 1, May 2016 The Cultures of Memory Massey University | ISSN 2253-1823 THE MEMORY WAKA MEMORY CONNECTION Volume 2, Number 1, May 2016 The Cultures of Memory Massey University | ISSN 2253-1823 Memory Connection is an international, peer-reviewed “The Cultures of Memory” Review Board journal project of The Memory Waka Research Group Jerry Blitefield, University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth (Massey University, NZ). Memory Connection provides Theresa Donofrio, Coe College a meeting place for multidisciplinary perspectives, Thomas R. -

Download Journal

MEMORY CONNECTION Volume 2, Number 1, May 2016 The Cultures of Memory Massey University | ISSN 2253-1823 THE MEMORY WAKA MEMORY CONNECTION Volume 2, Number 1, May 2016 The Cultures of Memory Massey University | ISSN 2253-1823 Memory Connection is an international, peer-reviewed “The Cultures of Memory” Review Board journal project of The Memory Waka Research Group Jerry Blitefield, University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth (Massey University, NZ). Memory Connection provides Theresa Donofrio, Coe College a meeting place for multidisciplinary perspectives, Thomas R. Dunn, University of Georgia discourses, and expressions of memory. The journal Victoria Gallagher, North Carolina State University aims to facilitate interdisciplinary dialogue that may lead S. Michael Halloran, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute to different ways of “seeing” and the creation of new Jette Barnholdt Hansen, University of Copenhagen knowledge. Margaret Lindauer, Virginia Commonwealth University Michael Rancourt, Portland State University Articles are subjected to a double, blind peer review Mitchell Reyes, Lewis and Clark College process. Sara VanderHaagen, University of Nevada Las Vegas Bradford Vivian, Penn State University Memory Connection is only available electronically at Elizabethada Wright, University of Minnesota Duluth http://www.memoryconnection.org The Memory Waka Board First published 2016 Chair: Professor Kingsley Baird, Massey University (NZ); Dr Paul Broks By The Memory Waka (UK); Professor Sir Mason Durie KNZM CNZM, Massey University College of Creative Arts Toi Rauwharangi (NZ); Professor Amos Kiewe, Syracuse University (USA); Professor Sally Massey University Te Kunenga ki Pu¯rehuroa J. Morgan, Massey University (NZ); Professor Charles E. Morris III, Museum Building Block 10 Syracuse University (USA); Dame Claudia Orange DNZM OBE, Museum Buckle Street of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (NZ); Professor Gary Peters, York St Wellington John University (UK); Professor Kendall R. -

The Kindred of the Kibbo Kift, 1920-1932

Cheng, Rachel K. (2016) “Something radically wrong somewhere”: the kindred of the Kibbo Kift, 1920-1932. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7693/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] “Something Radically Wrong Somewhere”: The Kindred of the Kibbo Kift, 1920-1932 Rachel K. Cheng M.A. History, B.A. History with a minor in Political Science Submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow FINAL COPY October 2016 2 Abstract This thesis examines the Kindred of the Kibbo Kift, a co-educational outdoors organisation that claimed to be a youth organisation and a cultural movement active from August 1920 to January 1932. Originally part of the Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, the Kibbo Kift offers rich insight into the interwar period in Britain specifically because it carried forward late Victorian and Edwardian ideology in how it envisioned Britain. Members constructed their own historical narrative, which endeavoured to place the organisation at the heart of British life. -

Download (1MB)

Parrish, David (2013) Jacobitism and the British Atlantic world in the age of Anne. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4697/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Jacobitism and the British Atlantic World in the Age of Anne Thesis submitted as a requirement for the degree Ph.D. David Parrish School of History College of Arts University of Glasgow October 2013 ii Abstract This thesis demonstrates the existence and significance of Jacobitism in the British Atlantic World, c. 1688-1727. Throughout the period under investigation, colonists were increasingly integrated into Britain’s partisan politics, religious controversies, and vibrant public sphere. This integrative process encouraged colonists to actively participate in British controversies. Moreover, this integration was complex and multi-faceted and included elements of a Tory political culture in addition to their Whig counterparts. During this period, colonists increasingly identified themselves and others according to British political and religious terminology. This was both caused and encouraged by imperial appointments, clerical appointments/SPG activity, and an increased consumption of British political news and commentary. -

Elite Scotswomen's Roles, Identity, and Agency in Jacobite Political

“PETTICOAT PATRONAGE.” Elite Scotswomen’s Roles, Identity, and Agency in Jacobite Political Affairs, 1688-1766. This Thesis is Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History of the University of Western Australia Humanities History Anita R. Fairney B.A. (Hons.) 2015 ABSTRACT The aim of this study is to uncover and analyse the identities and actions of the elite Scotswomen who supported and/or were involved in the political machinations between 1688 and 1766 in support of the Stuart cause. The strength of Jacobitism in Scotland and the national level of its support has been reappraised in recent years, revealing its centrality to Scottish political life and its strong patriotic agenda. However, the role and participation elite Scottish women played in over half a century’s political and military schemes, and their part in the preservation of Scottish Jacobite culture and community has not been examined. Through predominantly archival research I have identified and examined a few hundred elite women, who during this period were known, or referred to as Jacobites, in support of the exiled Stuart monarchy. These women came from the length and breadth of Scotland, with a variety of religious, political and familial identities, substantiating the national extent of Jacobitism in Scotland in the eighteenth century. In order to better understand the nature and range of female support I have made a prosopographical investigation of a cross section of these women. Furthermore, for the process of analysis I have organised the nature and type of elite Scotswomen’s support for Jacobitism into four main categories, which are examined each in their own chapter. -

Presbyterian Record Index 1950S

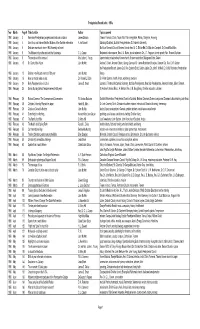

Presbyterian Record Index - 1950s Year Month Page # Title of article Author Topics covered 1950 January 3 Formosan Presbyterians progress amid national confusion James Dickson Taiwan, Formosa, China, Taipeh, Red Tide, immigration, Paktau, Siang-lian, Ho-peng 1950 January 4 John Knox and Andrew Melville: Builders of the Scottish reformation A. Ian Burnett Edinburgh Scotland, Scottish Presbyterianism, St. Andrew's University 1950 January 5 Dedicate new church where 1950 Assembly will meet MacVicar Memorial Church Montreal, church fires, Dr. C. Ritchie Bell, Dr. Malcolm Campbell, Dr. Donald MacMillan 1950 January 6 The Moderator tours the west and the Kootenays C. L. Cowan Mistawasis Indian reserve, Rev. J. A. Munro, church extension, Dr. J. T. Ferguson, church growth, Rev. Thomas Roulston 1950 January 9 The exodus and the remnant Mrs. Luther L. Young Japan mission, missionaries, Korean church, Korean repatriation, Mukogawa, Kobe, Osaka 1950 January 13 Dr. Grant of the Yukon John McNab Andrew S. Grant, Almonte Ontario, George Carmack, Dr. James Robertson, Klondyke, Dawson City, Rev. C. W. Gordon the Presbyterian Record, James Croil, Rev. Ephraim Scott, Golden Jubilee, Dr. John T. McNeill, Dr. W. M. Rochester, Presbyterian 1950 January 15 Editorial - the Record enters its 75th year John McNab history 1950 January 16 How our minds make us sick Dr. Russell L. Dicks Dr. Walter Cannon, health, illness, well-being, emotions 1950 January 24 Early Presbyterianism in U.S.A. James D. Smart Leonard J. Trinterud McCormick Seminary, Old Side Presbyterians, New Side Presbyterians, American history, Gilbert Tennent 1950 February 35 Sarnia Sunday School Teacher serves for 58 years St. -

Redskins in Epping Forest: John Hargrave, the Kibbo Kift and The

REDSKINS IN EPPING FOREST: JOHN HARGRAVE, THE KIBBO KIFT AND THE WOODCRAFT EXPERIENCE BY JOSEF FRANCIS CHARLES CRAVEN M.Phil A thesis submitted to the University of London for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History University College London Gower Street London SEPTEMBER 1998 1 ABSTRACT This thesis attempts to locate and explore the world of the Kibbo Kift, a camping and handicraft organisation established in 1920, by John Hargrave. The Kibbo Kift proved to be the most controversial, complex and colourful component of the English Woodcraft movement. The aim of this thesis is three-fold. First, to explain what is meant by the term Woodcraft and to examine the varied cultural influences that lay behind its growth in Edwardian England. Second, to give a more balanced and detailed historical account of the development of the Kibbo Kift, its secession from the Boy Scouts and its transformation into the Green Shirt Movement for Social Credit. Finally, it will orientate the movement within the English pro-rural tradition. In doing so, I hope to develop the idea of there being a collection of diverse and often contradictory strands within this culture, with the Kibbo Kift occupying a so-called pastoral Liberal-Transcendentalist stance, in contrast to the more agrarian Tory- Organic wing of the movement. It will be argued that the Kibbo Kift was ‘progressive’, forward looking and essentially ‘modem’, representing, in effect, a suburban interest in the inter-war countryside. However, the ultimate failure of the Kibbo Kift’s Woodcraft strategy adds to the argument that the English rural revival of this period was not as hegemonic as once thought and that pro-ruralism was limited in its cultural scope and impact.