State of Children's Development in Palestine in the Face of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nablus Salfit Tubas Tulkarem

Iktaba Al 'Attara Siris Jaba' (Jenin) Tulkarem Kafr Rumman Silat adh DhahrAl Fandaqumiya Tubas Kashda 'Izbat Abu Khameis 'Anabta Bizzariya Khirbet Yarza 'Izbat al Khilal Burqa (Nablus) Kafr al Labad Yasid Kafa El Far'a Camp Al Hafasa Beit Imrin Ramin Ras al Far'a 'Izbat Shufa Al Mas'udiya Nisf Jubeil Wadi al Far'a Tammun Sabastiya Shufa Ijnisinya Talluza Khirbet 'Atuf An Naqura Saffarin Beit Lid Al Badhan Deir Sharaf Al 'Aqrabaniya Ar Ras 'Asira ash Shamaliya Kafr Sur Qusin Zawata Khirbet Tall al Ghar An Nassariya Beit Iba Shida wa Hamlan Kur 'Ein Beit el Ma Camp Beit Hasan Beit Wazan Ein Shibli Kafr ZibadKafr 'Abbush Al Juneid 'Azmut Kafr Qaddum Nablus 'Askar Camp Deir al Hatab Jit Sarra Salim Furush Beit Dajan Baqat al HatabHajja Tell 'Iraq Burin Balata Camp 'Izbat Abu Hamada Kafr Qallil Beit Dajan Al Funduq ImmatinFar'ata Rujeib Madama Burin Kafr Laqif Jinsafut Beit Furik 'Azzun 'Asira al Qibliya 'Awarta Yanun Wadi Qana 'Urif Khirbet Tana Kafr Thulth Huwwara Odala 'Einabus Ar Rajman Beita Zeita Jamma'in Ad Dawa Jafa an Nan Deir Istiya Jamma'in Sanniriya Qarawat Bani Hassan Aqraba Za'tara (Nablus) Osarin Kifl Haris Qira Biddya Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Talfit Qusra Salfit As Sawiya Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Bani Zeid 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Sinjil Turmus'ayya. -

Community Resilience Development

Annexes Annex 1: Evaluation Terms of Reference Annex 2: The Concept of Resilience Annex 3: Bibliography Annex 4: List of Documents Reviewed Annex 5: List of people met: interviewees, focus groups, field visits Annex 6: List of field visits Annex 7: Sample of Projects for Document Review Annex 8: Maps, Vulnerability and Resilience Data Annex 9: Analysis of CRDP Project Portfolio Profile Annex 10: Vulnerability Analysis Annex 11: Universal Lessons on Gender-Sensitive Resilience-Based programming Annex 12: Field Work Calendar Annex 13: Achievements of Programme (Rounds 1-3) 1 Annex 1: Evaluation Terms of Reference 1. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT About the CRDP The Community Resilience Development Programme (CRDP) is the result of a fruitful cooperation between the Palestinian Government through the Ministry of Finance and Planning (MOFAP, the United Nations Development Programme/Programme of Assistance to the Palestinian People (UNDP/PAPP), and the Government of Sweden. In 2012, an agreement was signed between the Government of Sweden and UNDP/PAPP so as to support a three-year programme (from 2012 to 2016), with a total amount of SEK 90,000,000, equivalent to approximately USD 12,716,858. During the same year, the UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) joined the program and provided funds for the first year with an amount of £300,000, equivalent to USD 453,172. In 2013, the government of Austria joined the programme and deposited USD 4,202,585, (a final amount of approximately $557,414 remains to be deposited) to support the programme for two years. Finally, in 2014, the Government of Norway joined the programme with a contribution of USD 1,801,298 to support the programme for two years. -

Study on Small-Scale Agriculture in the Palestinian Territories Final

Study on Small-scale Agriculture in the Palestinian Territories Final Report Jacques Marzin. Cirad ART-Dév Ahmad Uwaidat. MARKAZ-Co Jean Michel Sourrisseau. CIRAD ART-Dév Submitted to: The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) June 2019 ACRONYMS ACAD Arab Center for Agricultural Development CIRAD Centre International de Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations GDP Gross National Product LSS Livestock Sector Strategy MoA Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture NASS National Agricultural Sector Strategy NGO Non-governmental organization PACI Palestinian Agricultural Credit Institution PCBS Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics PNAES Palestinian National Agricultural Extension Strategy PARPIF Palestinian Agricultural Risk Prevention and Insurance Fund SDGs Sustainable Development Goals (UN) SSFF Small-scale family farming UNHRC United Nations human rights council WFP World Food Programme 1 CONTENTS General introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and objectives of the study ...................................................................................................................... 5 Empirical material for this study ........................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgement and disclaimer .................................................................................................................... -

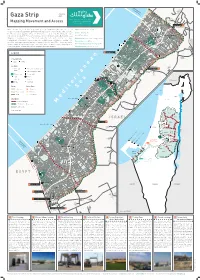

Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary

Zikim Karmiya No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles Yad Mordekhai January Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary Ar-Rasheed Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Sources: OCHA, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics of Statistics Bureau Central OCHA, Palestinian Sources: Erez Crossing 1 Al-Qarya Beit Hanoun Al-Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) Erez What is known today as the Gaza Strip, originally a region in Mandatory Palestine, was created Width 5.7-12.5 km / 3.5 – 7.7 mi through the armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt in 1949. From that time until 1967, North Gaza Length ~40 km / 24.8 mi Al- Karama As-Sekka the Strip was under Egyptian control, cut off from Israel as well as the West Bank, which was Izbat Beit Hanoun al-Jaker Road Area 365 km2 / 141 m2 Beit Hanoun under Jordanian rule. In 1967, the connection was renewed when both the West Bank and the Gaza Madinat Beit Lahia Al-'Awda Strip were occupied by Israel. The 1993 Oslo Accords define Gaza and the West Bank as a single Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Population 1,943,398 • 48% Under age 17 July 2019 Industrial Zone Ash-Shati Housing Project Jabalia Sderot territorial unit within which freedom of movement would be permitted. However, starting in the camp al-Wazeer Unemployment rate 47% 2019 Q2 Jabalia Camp Khalil early 90s, Israel began a gradual process of closing off the Strip; since 2007, it has enforced a full Ash-Sheikh closure, forbidding exit and entry except in rare cases. Israel continues to control many aspects of Percentage of population receiving aid 80% An-Naser Radwan Salah Ad-Deen 2 life in Gaza, most of its land crossings, its territorial waters and airspace. -

Chapter 5. Development Frameworks

Chapter 5 JERICHO Regional Development Study Development Frameworks CHAPTER 5. DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORKS 5.1 Socioeconomic Framework Socioeconomic frameworks for the Jericho regional development plan are first discussed in terms of population, employment, and then gross domestic product (GDP) in the region. 5.1.1 Population and Employment The population of the West Bank and Gaza totals 3.76 million in 2005, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) estimation.1 Of this total, the West Bank has 2.37 million residents (see the table below). Population growth of the West Bank and Gaza between 1997 and 2005 was 3.3%, while that of the West Bank was slightly lower. In the Jordan Rift Valley area, including refugee camps, there are 88,912 residents; 42,268 in the Jericho governorate and 46,644 in the Tubas district2. Population growth in the Jordan Rift Valley area is 3.7%, which is higher than that of the West Bank and Gaza. Table 5.1.1 Population Trends (1997-2005) (Unit: number) Locality 1997 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 CAGR West Bank and Gaza 2,895,683 3,275,389 3,394,046 3,514,868 3,637,529 3,762,005 3.3% West Bank 1,873,476 2,087,259 2,157,674 2,228,759 2,300,293 2,372,216 3.0% Jericho governorate 31,412 37,066 38,968 40,894 40,909 42,268 3.8% Tubas District 35,176 41,067 43,110 45,187 45,168 46,644 3.6% Study Area 66,588 78,133 82,078 86,081 86,077 88,912 3.7% Study Area (Excl. -

Area a Area B Area C Israeli Settlements the Separation Wall, Implemented the Separation Wall, Under Construction Dead Sea Jorda

Area A Area B Area C Israeli Settlements The Separation Wall, Implemented The Separation Wall, Under Construction Dead Sea Jordan River Natuar Reserv Area C embodies Palestine: terraced hills with olive groves where shepherds wander with their flocks and Special issue ghazal feed on misty mornings; striking wadis where foxes and mountain goats roam; the dry, rolling desert hills and green oases of al-ghor, the Jordan valley Area C that is less and less accessible to Palestinians; the disappearing Dead Sea where Palestinians no longer feel welcome to swim. Area C comprises sixty-one percent of the West Bank and is crucial for a viable Palestinian State. Connecting Palestine’s cities and villages, 4 Sustainable Urban Development in feeding its citizens, containing a wealth of natural and economic resources, the State of Palestine: An Opportunity housing immeasurable heritage and archeological treasures, it is among the most Interrupted beautiful places in the world - but not under Palestinian control and thus, as of yet, 6 MDGs to SDGs as a viable resource mostly untapped. In Area C, check points and the Separation 10 Area C of the West Bank: Strategic Wall restrict movement and access, which impacts livelihoods and restrains the Importance and Development Prospects entire economy; here the denial of building permits and house demolitions are as much a part of daily life as the uprooting of olive groves and the prevention of 18 International Experts Call for Fundamental Area A farmers from cultivating their fields and orchards. But Area C is also where the Area B Changes in Israel’s Approach to Planning Area C Israeli Settlements creative mind of Palestinians has found ingenious ways of showing resilience and The Segregation Wall, Existing and Development in Area C The Segregation Wall, Under Construction Dead Sea developing strategies for survival and development and in this issue you can read Jordan River 24 National Strategies for Area C Natuar Reserv about some of these. -

Gaza Strip West Bank

Afula MAP 3: Land Swap Option 3 Zububa Umm Rummana Al-Fahm Mt. Gilboa Land Swap: Israeli to Palestinian At-Tayba Silat Al-Harithiya Al Jalama Anin Arrana Beit Shean Land Swap: Palestinian to Israeli Faqqu’a Al-Yamun Umm Hinanit Kafr Dan Israeli settlements Shaked Al-Qutuf Barta’a Rechan Al-Araqa Ash-Sharqiya Jenin Jalbun Deir Abu Da’if Palestinian communities Birqin 6 Ya’bad Kufeirit East Jerusalem Qaffin Al-Mughayyir A Chermesh Mevo No Man’s Land Nazlat Isa Dotan Qabatiya Baqa Arraba Ash-Sharqiya 1967 Green Line Raba Misiliya Az-Zababida Zeita Seida Fahma Kafr Ra’i Illar Mechola Barrier completed Attil Ajja Sanur Aqqaba Shadmot Barrier under construction B Deir Meithalun Mechola Al-Ghusun Tayasir Al-Judeida Bal’a Siris Israeli tunnel/Palestinian Jaba Tubas Nur Shams Silat overland route Camp Adh-Dhahr Al-Fandaqumiya Dhinnaba Anabta Bizzariya Tulkarem Burqa El-Far’a Kafr Yasid Camp Highway al-Labad Beit Imrin Far’un Avne Enav Ramin Wadi Al-Far’a Tammun Chefetz Primary road Sabastiya Talluza Beit Lid Shavei Shomron Al-Badhan Tayibe Asira Chemdat Deir Sharaf Roi Sources: See copyright page. Ash-Shamaliya Bekaot Salit Beit Iba Elon Moreh Tire Ein Beit El-Ma Azmut Kafr Camp Kafr Qaddum Deir Al-Hatab Jammal Kedumim Nablus Jit Sarra Askar Salim Camp Chamra Hajja Tell Balata Tzufim Jayyus Bracha Camp Beit Dajan Immatin Kafr Qallil Rujeib 2 Burin Qalqiliya Jinsafut Asira Al Qibliya Beit Furik Argaman Alfe Azzun Karne Shomron Yitzhar Itamar Mechora Menashe Awarta Habla Maale Shomron Immanuel Urif Al-Jiftlik Nofim Kafr Thulth Huwwara 3 Yakir Einabus -

U.S. Security Assistance to the Palestinian Authority

U.S. Security Assistance to the Palestinian Authority Jim Zanotti Analyst in Middle Eastern Affairs January 8, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R40664 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress U.S. Security Assistance to the Palestinian Authority Summary Since shortly after the establishment of limited Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza Strip in the mid-1990s, the United States has periodically provided assistance to the Palestinian Authority (PA) for civil security and counterterrorism purposes. Following the death of Yasser Arafat in late 2004 and the election of Mahmoud Abbas as his successor as PA President in early 2005, then-U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice created the office of U.S. Security Coordinator (USSC) for Israel and the Palestinian Authority to help reform, train, and equip PA security forces which had been personally beholden to Arafat and his political allies. Previous Israeli-Palestinian efforts at security cooperation collapsed during the second Palestinian intifada that took place earlier this decade. Since Hamas gained control of the Gaza Strip in June 2007, Lieutenant General Keith Dayton, head of the USSC since November 2005, and the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) have helped with the “gendarmerie-style” training of West Bank-based PA security personnel. As of June 2009, approximately 400 Presidential Guardsmen and 2,200 National Security Forces troops have been trained at the Jordan International Police Training Center (JIPTC) near Amman. All troops, new or already serving, are vetted for terrorist links, human rights violations, and/or criminal records by the State Department, Israel, Jordan, and the PA before they are admitted to U.S.-sponsored training courses at JIPTC. -

Restoration of the Besor-Hebron-Be'er Sheva Stream a Transboundary Project Supported by the JNF Parsons Water Fund

Restoration of the Besor-Hebron-Be'er Sheva Stream A Transboundary Project Supported by the JNF Parsons Water Fund Center for Transboundary Water Management, Arava Institute for Environmental Studies Principle Investigators: Dr. Clive Lipchin, Eng. Shira Kronich Second Year Interim Report (January 1st, 2013-August 31st, 2013) 1 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 Background .....................................................................................................................................4 Our Work ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Results ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Water Quality Monitoring Results .............................................................................................. 7 Socioeconomic Characterisation of the Watershed .................................................................. 11 Description of Pollution Sources in the West Bank .................................................................. 13 Olive Oil Production in the Palestinian Authority................................................................. 13 Stone and Marble Production in the Palestinian Authority .................................................. 16 Leather Tanning Production -

Tubas City Profile

Tubas City profile Produced by The Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem In cooperation with Funded by February, 2006 This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Community. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Community Socio-Economic Surveillance System Tubas Governorate Table of Content LOCATION AND PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS 2 HISTORY 3 DEMOGRAPHY 3 RELIGIOS AND ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES 5 ECONOMY 5 EDUCATION 7 HEALTH 8 INFRASTRUCTURE 9 AGRICULTURE 10 IMPACT OF OCCUPATION PRACTICES 10 PLANS AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS 11 REFERENCES 11 1 Socio-Economic Surveillance System Tubas Governorate Tubas city profile Location and Physical characteristics TUBAS is a Palestinian city which is located in the north eastern part of the West Bank. The city is located to the west of the Governorate of Tubas. It is bordered by Tayasir and Alaqaba villages to the east, Aqqaba to the north, Aljadedah and Sereas villages (Jenin Governorate) to the west and Tamun and Alfarha to the south. Map 1: Tubas city location and borders The total area of Tubas city is 295,123 dunums, which represents approximately 55.6 % of the Tubas Governorate's land area. 3000 dunums are classified as 'built up' areas, whilst 150,000 dunums are agricultural, and 180,000 further dunums have been confiscated by Israeli occupation. Tubas city is the administrative center of the Governorate of Tubas and also the largest locality. Whereas most of the governorate is in the Jordan valley, Tubas itself is located in the hills of the West Bank at the moderate elevation of 362 m above sea level. -

Supplementary Table 1: Governorates and Localities Included in the Households Sample

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open Supplementary Table 1: Governorates and localities included in the households sample Governorate Locality Jenin Sir Jenin Anza Jenin Al Araqa Jenin Al Mughayyir Jenin Al Fandaqumiya Jenin Al Judeida Jenin Ajja Jenin Birqin Jenin Meithalun Jenin Jaba Jenin Silat al Harithiya Jenin Arraba Jenin Yabad Jenin Al Yamun Jenin Qabatiya Jenin Jenin Tubas Ras al Faraa Tubas Aqqaba Tubas Tammun Tubas Tubas Tulkarm Kafa Tulkarm Kafr Jammal Tulkarm Kafr al Labad Tulkarm Nur Shams Camp Tulkarm Bala Tulkarm Tulkarm Camp Tulkarm Attil Tulkarm Tulkarm Nablus Iraq Burin Nablus Qusin Nablus As Sawiya Nablus Majdal Bani Fadil Nablus Sabastiya Nablus Ein Beit el Ma Camp Nablus Beit Dajan Nablus Qusra Nablus Askar Camp )al Qadeem( Nablus Awarta Nablus Asira ash Shamaliya Nablus Aqraba Qutob N, et al. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e044552. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044552 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open Nablus Beit Furik Nablus Balata Camp Nablus Nablus Qalqiliya Kafr Laqif Qalqiliya Jinsafut Qalqiliya Sanniriya Qalqiliya Azzun Qalqiliya Qalqiliya Salfit Deir Istiya Salfit Haris Salfit Biddya Salfit Salfit Ramallah & Al- Shabtin Bireh Ramallah & Al- Ein Arik Bireh Ramallah & Al- Beitin Bireh Ramallah & Al- Ein Yabrud Bireh Ramallah & Al- Arura Bireh Ramallah & Al- Beitillu Bireh Ramallah & Al- Deir Abu Mashaal Bireh Ramallah & Al- Khirbet Abu Falah Bireh Ramallah & Al- Beit Ur at Tahta Bireh Ramallah & Al- Shuqba Bireh Ramallah & Al- Qibya Bireh Ramallah & Al- Al Jalazun Camp Bireh Ramallah & Al- Beituniya Bireh Ramallah & Al- Ramallah Bireh Ramallah & Al- Al Bireh Bireh Jericho & Al- Ein as Sultan Camp Aghwar Jericho & Al- Jericho )Ariha( Aghwar Jerusalem Ash Sheikh Sad Qutob N, et al. -

Monthly Violations Report September 2020 the Israeli Systematic Attacks

Monthly Violations Report September 2020 The Israeli systematic attacks on the Palestinian agricultural sector in the West Bank and Gaza Strip UAWC’s Agricultural Committees all over the west bank and Gaza strip monitored the attacks of the Israeli occupation forces and settlers against the Palestinian agricultural sector in the West Bank during the month of September. This report documents Israeli bulldozers demolishing Palestinian agricultural facilities, in addition uprooting over 600 trees. This report documents demolition operations and military notices for more than 13 agricultural facilities, the demolition of two wells for water collection, the uprooting of more than 1400 trees, and the razing and seizing of more than 130 dunums, in a continuous escalation of land seizing and settlement expansion. Demolishing Agricultural Facilities Occupation forces demolishing houses in Yarza/ Jordan Valley • On September 02, 2020, the occupation forces demolished a 300-square-meter barracks in the area of Jebna in Masafer Yatta, Hebron. • On September 02, 2020, the occupation forces demolished a 50-cubic-meter water well in the village of Birin, west of Bani Naim town, to the east of Hebron. • On September 07, 2020, the Israeli occupation authorities delivered military demolition notices for against two barracks for livestock in the village of Kisan, east of Bethlehem. It is noteworthy that the 1 village of Kisan undergoes a fierce settlement attack, and is witnessing the largest settlement project in Bethlehem, which threatens to seize about 3,500 dunums. • On September 14, 2020, a military demolition notice was delivered for an 80-square-meter sheep pen, built of tin, in the village of Twana, to the east of Yatta, south of Hebron governorate.