Gabriel Fauré

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré : Teosten Yhtenäistettyjen Nimekkeiden Ohjeluettelo / Heikki Poroila

Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja 108 Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré Teosten yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo Heikki Poroila Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys Helsinki 2012 Julkaisija Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys ry Ulkoasu Heikki Poroila © Heikki Poroila 2012 Toinen laitos, verkkoversio 2.0 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré : Teosten yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo / Heikki Poroila. – Toinen laitos, verkkoversio 2.0. – Helsinki : Suomen musiikkikirjas- toyhdistys, 2012. – 19 s. – (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja, ISSN 0784-0322 ; 108) – ISBN 952-5363-07-4 (PDF) ISBN 952-5363-07-4 (PDF) Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré 2 Luettelon käyttäjälle GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845 – 1924) ei ole kirjastodokumentoinnin näkökulmasta erityisen hankala sävel- täjä. Useiden sävellysten pysyvä suosio antaa kuitenkin aihetta koko tuotannon standardointiin. Varsinaista teosluetteloa ei ole olemassa, vaan tiedot pohjautuvat keskeisissä hakuteoksissa oleviin luetteloihin. Pääosa Faurén sävellyksistä on opusnumeroituja, numerottomia on vain muutama kymmenen, nekin pääosin vähemmän tunnettuja teoksia. Opusnumerolistassa näyttäisi puuttuvan muutamia numeroita (9, 53, 60, 64, 71, 81, 100), joita ei ole ainakaan toistaiseksi löytynyt. Helsingin Viikissä lokakuussa 2012 Heikki Poroila Yhtenäistetty Gabriel Fauré 3 Opusnumeroidut teokset [Le papillon et la fleur, op1, nro 1] ► 1861. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Victor Hugo. ■ La pauvre fleur disait au papillon céleste [Mai, op1, nro 2] ► 1862. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Victor Hugo. ■ Puis-que Mai tout en fleurs dans les prés nous réclame [Dans les ruines d’une abbaye, op2, nro 1] ► 1866. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Victor Hugo. ■ Seuls, tous deux, ravis, chantants,comme on s’aime [Les matelots, op2, nro 2] ► 1870. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Théophile Gautier. ■ Sur l’eau bleue et profonde [Seule!, op3, nro 1] ► 1870. Lauluääni ja piano. Teksti Théophile Gautier. ■ Dans un baiser, l’onde au ravage dit ses douleurs [Sérénade toscane, op3, nro 2] ► 1878. -

Rachel Podger

Rachel Podger “Rachel Podger, the unsurpassed British glory of the baroque violin,” (The Times) has established herself as a leading interpreter of the Baroque and Classical. She was the first woman to be awarded the prestigious Royal Academy of Music/Kohn Foundation Bach Prize in October 2015, Gramophone Artist of the Year 2018, and the Ambassador for REMA’s Early Music Day 2020. A creative programmer, Rachel is the founder and Artistic Director of Brecon Baroque Festival and her ensemble Brecon Baroque. As a director and soloist, Rachel has enjoyed countless collaborations including with Robert Levin, Jordi Savall, Masaaki Suzuki, Kristian Bezuidenhout, VOCES8, Robert Hollingworth and I Fagiolini, European Union Baroque Orchestra, English Concert, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Academy of Ancient Music, Holland Baroque Society, Tafelmusik (Toronto), the Handel and Haydn Society, Berkeley Early Music, and Oregon Bach Festival. Rachel has won numerous awards including two Baroque Instrumental Gramophone Awards for La Stravaganza (2003) and Biber Rosary Sonatas (2016), the Diapason d’Or de l’année in the Baroque Ensemble category for her recording of the La Cetra Vivaldi concertos (2012), two BBC Music Magazine awards in the instrumental category for Guardian Angel (2014) and the concerto category for the complete Vivaldi L’Estro Armonico concertos (2016). A dedicated educator, she holds the Micaela Comberti Chair for Baroque Violin (founded in 2008) at the Royal Academy of Music and the Jane Hodge Foundation International Chair in Baroque Violin at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama. Rachel has a relationship with The Juilliard School in New York where she visits regularly. -

May 2018 List

May 2018 Catalogue Issue 25 Prices valid until Wednesday 27 June 2018 unless stated otherwise 0115 982 7500 [email protected] Your Account Number: {MM:Account Number} {MM:Postcode} {MM:Address5} {MM:Address4} {MM:Address3} {MM:Address2} {MM:Address1} {MM:Name} 1 Welcome! Dear Customer, Glorious sunshine and summer temperatures prevail as this foreword is being written, but we suspect it will all be over by the time you are reading it! On the plus side, at least that means we might be able to tempt you into investing in a little more listening material before the outside weather arrives for real… We were pleasantly surprised by the number of new releases appearing late April and into May, as you may be able to tell by the slightly-longer-than-usual new release portion of this catalogue. Warner & Erato certainly have plenty to offer us, taking up a page and half of the ‘priorities’ with new recordings from Nigel Kennedy, Philippe Jaroussky, Emmanuel Pahud, David Aaron Carpenter and others, alongside some superbly compiled boxsets including a Massenet Opera Collection, performances from Joseph Keilberth (in the ICON series), and two interesting looking Debussy collections: ‘Centenary Discoveries’ and ‘His First Performers’. Rachel Podger revisits Vivaldi’s Four Seasons for Channel Classics (already garnering strong reviews), Hyperion offer us five new titles including Schubert from Marc-Andre Hamelin and Berlioz from Lawrence Power and Andrew Manze (see ‘Disc of the Month’ below), plus we have strong releases from Sandrine Piau (Alpha), the Belcea Quartet joined by Piotr Anderszewski (also Alpha), Magdalena Kozena (Supraphon), Osmo Vanska (BIS), Boris Giltberg (Naxos) and Paul McCreesh (Signum). -

Le Monde Galant

The Juilliard School presents Le Monde Galant Juilliard415 Nicholas McGegan, Director Recorded on May 1, 2021 | Peter Jay Sharp Theater FRANCE ANDRÉ CAMPRA Ouverture from L’Europe Galante (1660–1744) SOUTHERN EUROPE: ITALY AND SPAIN JEAN-MARIE LECLAIR Forlane from Scylla et Glaucus (1697–1764) Sicilienne from Scylla et Glaucus CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK Menuet from Don Juan (1714–87) MICHEL RICHARD DE LALANDE Chaconne légère des Maures from Les Folies (1657–1726) de Cardenio CHARLES AVISON Con Furia from Concerto No. 6 in D Major, (1709-70) after Domenico Scarlatti CELTIC LANDS: SCOTLAND AND IRELAND GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN L’Eccossoise from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D19 (1681–1767) NATHANIEL GOW Largo’s Fairy Dance: The Fairies Advancing and (1763–1831) Fairies Dance Cullen O’Neil, Solo Cello TELEMANN L’Irlandoise from Overture in D Minor, TVW55:d2 EASTERN EUROPE: POLAND, BOHEMIA, AND HUNGARY ARR. TELEMANN Danse de Polonie No. 4, TWV45 Polonaise from Concerto Polonois, TWV43:G7 Danse de Polonie No. 1, TWV45 La Hanaquoise, TWV55:D3 TRADITIONAL Three 18th-century Hanák folk tunes RUSSIA TELEMANN Les Moscovites from Overture in B-flat Major, TWV55:B5 Program continues 1 EUROPE DREAMS OF THE EAST: THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE TELEMANN Les Janissaries from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D17 Mezzetin en turc from Overture-Burlesque in B-flat Major, TWV55:B8 PERSIA AND CHINA JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU Air pour Borée from Les Indes galantes (1683–1764) Premier Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Seconde Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Entrée des Chinois -

The Juilliard School Presents Juilliard415 Rachel Podger

The Juilliard School presents Juilliard415 Rachel Podger, Director and Violin Recorded on March 31, 2021 Peter Jay Sharp Theater Madness and Enchantment: Music of the English 17th Century by Purcell, Clarke, and Matteis Sett 1: Music from Shakespeare's Plays by Purcell and Clarke JEREMIAH CLARKE Overture to Titus Andronicus (c. 1674-1707) HENRY PURCELL First Music: Hornpipe from The Fairy Queen (1659-95) Second Music: Air from The Fairy Queen Rondeau from The Fairy Queen Curtain Tune from Timon of Athens First Act Tune: Jig from The Fairy Queen Song Tune: “If Love’s a Sweet Passion” from The Fairy Queen Dance for the Fairies from The Fairy Queen Second Act: Introduction from King Arthur Air from King Arthur Air: “How Blest Are Shepherds” from King Arthur Air: “Fairest Isle” from King Arthur Passacaglia: “How Happy the Lovers” from King Arthur Sett 2: Chamber Music by Purcell and Matteis PURCELL Pavan in B Flat, Z. 750 Three Parts Upon a Ground, Z. 731 Fantasia Upon One Note, Z. 745 Fantasia à 4 in G Major, Z. 742 NICOLA MATTEIS Suite in D Minor (c. 1670-1713) Preludio in D la sol rè Grave Ground in D la sol re per far la mano Sett 3: Music for The Tempest MATTHEW LOCKE First Musick: Introduction (c. 1621-77) Galliard Gavot Second Musick: Sarabrand Lilk Curtain Tune First Act Tune: Rustick Air Second Act Tune: Minoit Third Act Tune: Corant Fourth Act Tune: A Martial Jigge Conclusion: A Canon 4 in 2 Welcome to the 2020-21 Historical Performance season! The Historical Performance movement began as a revolution: a reimagining of musical conventions, a rediscovery of instruments, techniques, and artworks that inspire and teach us, and a celebration of diversity in repertoire. -

Gabriel Fauré

Intégrale GABRIEL pour voix des mélodies et piano FAURÉ HÉLÈNE GUILMETTE JULIE BOULIANNE ANTONIO FIGUEROA MARC BOUCHER OLIVIER GODIN | piano Érard (1859) ACD2 2741 4 CD Intégrale GABRIEL pour voix des mélodies et piano FAURÉ Hélène Guilmette soprano Julie Boulianne mezzo-soprano Antonio Figueroa ténor | tenor Marc Boucher baryton | baritone Olivier Godin piano Érard (1859) CD 1 1 w LE PAPILLON ET LA FLEUR, op.1 no 1 HG [ 2:18 ] 14 w AUBADE, op. 6 no 1 MB [ 1:45 ] 2 w MAI, op. 1 no 2 AF [ 1:49 ] 15 w TRISTESSE, op. 6 no 2 MB [ 2:24 ] 3 w PUISQUE J’AI MIS MA LÈVRE AF [ 3:15 ] 16 w SYLVIE, op. 6 no 3 AF [ 2:22 ] 4 w TRISTESSE D’OLYMPIO MB [ 3:50 ] 17 w APRÈS UN RÊVE, op. 7 no 1 MB [ 2:49 ] 5 w DANS LES RUINES D’UNE ABBAYE, op. 2 no 1 AF [ 1:50 ] 18 w HYMNE, op. 7 no 2 AF [ 1:40 ] 6 w LES MATELOTS, op. 2 no 2 MB [ 1:20 ] 19 w BARCAROLLE, op. 7 no 3 AF [ 1:56 ] 7 w L’AURORE, op. posth HG [ 1:24 ] 20 w AU BORD DE L’EAU, op. 8 no 1 JB [ 2:03 ] 8 w SEULE, op. 3 no 4 JB [ 2:50 ] 21 w ICI-BAS, op. 8 no 3 HG [ 1:19 ] 9 w LA CHANSON DU PÊCHEUR, op. 4 no 1 MB [ 2:57 ] 22 w LA RANÇON, op. 8 no 2 MB [ 1:58 ] 10 w LYDIA, op. -

Rachel/Mozart Vol.2 FRONT 22805 05-07-2005 19:49 Pagina 1

Rachel/Mozart vol.2_FRONT_22805 05-07-2005 19:49 Pagina 1 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) W.A. Mozart VOLUME 2 complete sonatas for keyboard and violin complete sonatas for keyboard and violin Gary Cooper fortepiano volume Rachel Podger violin 2 Sonata in C Major KV 303 (293c) 1 Adagio / Molto Allegro 5 CHANNEL CLASSICS CHANNEL CLASSICS 2 Gary Cooper Tempo di Menuetto 5.48 CCS SA 22805 CCS SA 22805 fortepiano Sonata in D Major KV 7 (1763-64) Rachel Podger 3 Allegro molto 4.41 4 & 2005 Adagio 6.25 Production & Distribution baroque violin 5 Menuet I & II 2.45 Channel Classics Records bv [email protected] Sonata in G Major KV 301 (293a) www.channelclassics.com 6 Allegro con spirito 8.11 7 Allegro 5.30 Made in Germany Sonata in F Major KV 30 (1766) •english 8 Adagio 7.17 •deutsch 9 Rondeau 2.55 •français Sonata in E flat Major KV 481 10 Molto allegro 6.58 STEMRA 11 Adagio 8.45 12 Allegretto 7.50 Total time 73.22 INSTRUMENTS SURROUND/5.0 fortepiano:Anton Walter,Vienna 1795; copy by Derek Adlam 1987 this recording can be violin: Pesarinius 1739 played on all cd-players MOZART 2_BOOKLET_22805 05-07-2005 19:47 Pagina 1 (...) Podger knows how to step aside with allowing her part to seem entirely super- fluous. This should be an outstanding series, and the perfectly natural SACD audio options greatly helps the musicians bring Mozart to life. Strings Magazine (…) Podger and Cooper’s masterly first endeavour captures the heart and the mind of the master. -

Juilliard415 Rachel Podger, Director and Violin

Juilliard415 Rachel Podger, Director and Violin The Juilliard School presents Juilliard415 Rachel Podger, Director and Violin Recorded on March 31, 2021 Peter Jay Sharp Theater Madness and Enchantment: Music of the English 17th Century by Purcell, Clarke, and Matteis Sett 1: Music from Shakespeare's Plays by Purcell and Clarke JEREMIAH CLARKE Overture to Titus Andronicus (c. 1674-1707) HENRY PURCELL First Music: Hornpipe from The Fairy Queen (1659-95) Second Music: Air from The Fairy Queen Rondeau from The Fairy Queen Curtain Tune from Timon of Athens First Act Tune: Jig from The Fairy Queen Song Tune: “If Love’s a Sweet Passion” from The Fairy Queen Dance for the Fairies from The Fairy Queen Second Act: Introduction from King Arthur Air from King Arthur Air: “How Blest Are Shepherds” from King Arthur Air: “Fairest Isle” from King Arthur Passacaglia: “How Happy the Lovers” from King Arthur Sett 2: Chamber Music by Purcell and Matteis PURCELL Pavan in B Flat, Z. 750 Three Parts Upon a Ground, Z. 731 Fantasia Upon One Note, Z. 745 Fantasia à 4 in G Major, Z. 742 NICOLA MATTEIS Suite in D Minor (c. 1670-1713) Preludio in D la sol rè Grave Ground in D la sol re per far la mano Program continues 1 Sett 3: Music for The Tempest MATTHEW LOCKE First Musick: Introduction (c. 1621-77) Galliard Gavot Second Musick: Sarabrand Lilk Curtain Tune First Act Tune: Rustick Air Second Act Tune: Minoit Third Act Tune: Corant Fourth Act Tune: A Martial Jigge Conclusion: A Canon 4 in 2 Welcome to the 2020-21 Historical Performance season! The Historical Performance movement began as a revolution: a reimagining of musical conventions, a rediscovery of instruments, techniques, and artworks that inspire and teach us, and a celebration of diversity in repertoire. -

Rondeau Minuet from the Gordion Knot Untied

The Juilliard School presents Juilliard415 Kristian Bezuidenhout, Harpsichord and Director Recorded on April 10, 2021 Peter Jay Sharp Theater HENRY PURCELL Music of the Theater (1659-95) Overture to Dioclesian Hornpipe from King Arthur Rondeau Minuet from The Gordion Knot Untied First Act Tune from The Virtuous Wife Second Music from The Virtuous Wife Rondeau from The Indian Queen Chacony in G Minor J.S. BACH Contrapunctus XIV from The Art of Fugue, arr. for flute, oboe, and four- (1685-1750) part strings BACH Harpsichord Concerto in D Minor, BWV 1052 Allegro Adagio Allegro GEORG PHILIPP Sonata à 5 for two violins, two violas, and basso continuo in G Minor, TELEMANN TWV 44:33 (1681-1767) Grave Allegro Adagio Vivace Welcome to the 2020-21 Historical Performance season! The Historical Performance movement began as a revolution: a reimagining of musical conventions, a rediscovery of instruments, techniques, and artworks that inspire and teach us, and a celebration of diversity in repertoire. It is also a conversation with the past, a past whose legacy of racism and colonialism has silenced and excluded too many voices from being heard. We do not seek simply to recreate what might have been, but to imagine what should be. We embrace Juilliard's values of equity, diversity, inclusion, and belonging, through voices heard anew and historical works presented with empathetic perspectives, and we reject discrimination, exclusion, and marginalization. We recognize that we study and work on the traditional homeland of those who preceded us (see Juilliard's land acknowledgement statement, below). We are committed to collaborations with scholars and performers from a diverse range of viewpoints and backgrounds, and we seek to share the music we love so much in active engagement with the community around us. -

Le Monde Galant

The Juilliard School presents Le Monde Galant Juilliard415 Nicholas McGegan, Director Recorded on May 1, 2021 Peter Jay Sharp Theater France ANDRÉ CAMPRA (1660–1744) Ouverture from L’Europe Galante Southern Europe: Italy and Spain JEAN-MARIE LECLAIR (1697–1764) Forlane from Scylla et Glaucus Sicilienne from Scylla et Glaucus CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK (1714–87) Menuet from Don Juan MICHEL RICHARD DE LALANDE (1657–1726) Chaconne légère des Maures from Les Folies de Cardenio CHARLES AVISON (1709-70) Con Furia from Concerto No. 6 in D Major, after Domenico Scarlatti Celtic Lands: Scotland and Ireland GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN (1681–1767) L’Eccossoise from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D19 NATHANIEL GOW (1763–1831) Largo’s Fairy Dance: The Fairies Advancing and Fairies Dance Cullen O’Neil, Solo Cello TELEMANN L’Irlandoise from Overture in D Minor, TVW55:d2 Eastern Europe: Poland, Bohemia, and Hungary ARR. TELEMANN Danse de Polonie No. 4, TWV45 Polonaise from Concerto Polonois, TWV43:G7 Danse de Polonie No. 1, TWV45 La Hanaquoise, TWV55:D3 TRADITIONAL Three 18th-century Hanák folk tunes Russia TELEMANN Les Moscovites from Overture in B-flat Major, TWV55:B5 Europe Dreams of the East: The Ottoman Empire TELEMANN Les Janissaries from Overture in D Major, TWV55:D17 Mezzetin en turc from Overture-Burlesque in B-flat Major, TWV55:B8 Persia and China JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU (1683–1764) Air pour Borée from Les Indes galantes Premier Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Seconde Air pour Zéphire from Les Indes galantes Entrée des Chinois from Les Paladins -

Virtual BACH FESTIVAL OREGON BACH FESTIVAL 2021

LISTENING GUIDE June 25- July 11, 2021 OREGONVirtual BACH FESTIVAL OREGON BACH FESTIVAL 2021 Welcome to the 2021 Oregon Bach Festival In times of uncertainty, music is a constant in our lives. Music offers catharsis. It keeps us entertained, conjures memories, and expresses our deepest emotions.Music is everywhere. And during this divisive and tumultuous moment, we’re grateful that music is a powerful and relentless force that universally connects us. As we continue to fight a world-wide pandemic together, OBF invites you to join the global community of music lovers who will listen and watch the 2021 virtual Festival from the comfort and safety of their own spaces.All events are presented free and on-demand. A new concert is posted every day at noon and, unless otherwise noted, will remain available throughout the Festival. Whether you’re watching at home alone or you’re gathered with a socially distanced group of friends for a watch party, we hope you enjoy the 2021 slate of brilliant works. We’ll see you for a return to live music in 2022! June 25 Bach Listening Room with Matt Haimovitz June 25 Dunedin Consort: Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos 5 & 6 June 26 Paul Jacobs: Handel & Bach Recital June 27 To the Distant Beloved with Tyler Duncan June 28 Visions of the Future Part 1: Miguel Harth-Bedoya (48 hours only) June 29 Dunedin Consort: Lagrime Mie June 30 Visions of the Future Part 2: Eric Jacobsen (48 hours only) July 1 Emerson String Quartet July 2 Visions of the Future Part 3: Julian Wachner (48 hours only) July 3 Lara Downes presents -

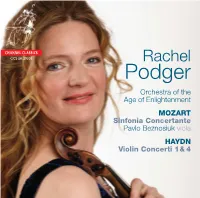

Podgerbooklet 11-11-2009 09:39 Pagina 1

29309podgerBooklet 11-11-2009 09:39 Pagina 1 CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 29309 Rachel Podger Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment MOZART Sinfonia Concertante Pavlo Beznosiuk viola HAYDN Violin Concerti 1& 4 29309podgerBooklet 11-11-2009 09:39 Pagina 2 photos: Sam Peach 2 29309podgerBooklet 11-11-2009 09:39 Pagina 3 Rachel Podger and Partitas for Solo Violin and his Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord (with Trevor achel Podger is one of the most creative Pinnock) were both awarded first place by the Rtalents to emerge in the field of period BBC’s ‘Building a Library’ programme. Her performance over the last decade, establishing recording of Telemann’s Twelve Fantasies for herself as a leading interpreter of the music of Solo Violin won the prestigious Diapason the Baroque and Classical periods. She was d’Or, as did the 2003 recording of Vivaldi’s 12 educated in Germany and in England at the violin concertos ‘La Stravaganza’ which went Guildhall School of Music and Drama where on to winning the 2003 Gramophone Award she studied with David Takeno and Michaela for Best Baroque Instrumental recording. Her Comberti. Duo with Gary Cooper (keyboards) has en- After beginnings with The Palladian En- joyed tremendous success through their semble and Florilegium, she was leader of The Mozart Sonata recording project which is English Concert from 1997 to 2002. Since then now complete, winning many awards along she has been in demand as a soloist and guest the way including Gramophone's 'Editors's director all over the Baroque music world and Choice' (twice) and the Diapaison d'Or (three has enjoyed meeting orchestras from all over times).