Closing the Gap: Public and Private Funding Strategies for Neighborhood Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Background

DRAFT SOUTHEAST LIAISON DISTRICT PROFILE DRAFT Introduction In 2004 the Bureau of Planning launched the District Liaison Program which assigns a City Planner to each of Portland’s designated liaison districts. Each planner acts as the Bureau’s primary contact between community residents, nonprofit groups and other government agencies on planning and development matters within their assigned district. As part of this program, District Profiles were compiled to provide a survey of the existing conditions, issues and neighborhood/community plans within each of the liaison districts. The Profiles will form a base of information for communities to make informed decisions about future development. This report is also intended to serve as a tool for planners and decision-makers to monitor the implementation of existing plans and facilitate future planning. The Profiles will also contribute to the ongoing dialogue and exchange of information between the Bureau of Planning, the community, and other City Bureaus regarding district planning issues and priorities. PLEASE NOTE: The content of this document remains a work-in-progress of the Bureau of Planning’s District Liaison Program. Feedback is appreciated. Area Description Boundaries The Southeast District lies just east of downtown covering roughly 17,600 acres. The District is bordered by the Willamette River to the west, the Banfield Freeway (I-84) to the north, SE 82nd and I- 205 to the east, and Clackamas County to the south. Bureau of Planning - 08/03/05 Southeast District Page 1 Profile Demographic Data Population Southeast Portland experienced modest population growth (3.1%) compared to the City as a whole (8.7%). -

9 10 11 13 12 3 6 7 8 1 2 4 5 3 Portland SUNDAY

e e v e v e v A v A A s A a s i k n c i e p i r b p l i g w s A n h e t s o i r v N s o C A s e i l B v N a M i A N N c e e e r h N L v t v v a e 9 A A g A o N Alberta St m NE Alberta St NE Alberta St NE Alberta St h o h h E e t t t n e m NEAve 7th NE A lberta St v NEAve 8th N 8 e A 7 v 9 N Alberta St o e v e NE Alberta Ct A e v 1 1 1 e A N e N Humboldt St v v e C e v NE Alberta Ct A h v v A v A mboldt St Hu d E E B N E e t e E e A NE Wygant St l N A r A d n A v a v v 5 n N N NE 16th Ave NE 16th N NE 20th Ave N H Ave NE 22nd umboldt St NE 21st Ave a NE Wygant St l e n s P 2 5 d t A A d a A a N Humboldt St i v r 2 n P 5 i o n g n h r h i h n ant St g 6 N E W NE Wy 3 N ygant St t s A t t a a h u h E N Anchor St e 7 nt Ave NE 57th t S NE Wyga t 8 v t N e 6 C 4 NE Wygant St yl E c e o n 7 i N King School Park 4 h D NE Going St 3 n r 3 E s a N o 1 n n a s M N Wygant St i E e N N i E n E M e v M N Blandena E S N t M N NE 35th Ave NE 35th l N NE Going St N NE Going St M NE 60th Ave NE 60th A A N NE Going St N v Madrona Park N e N d N Blandena St N NE 35th Pl NE Going St n 2 7 E N Going St N Going St NE Going St NE Going St N NE Goin e N e g St Going Ct e NE 77th Ave NE 77th v v v A A A N P ort Cen d ter d W h NE Prescott St ay d r NE 74th Ave 74th NE NE ott St t Presc r v N ott St NE Prescott St e l NE Prescott St Presc 3 e 4 t 3 NE Prescott S v v 8 2 B 2 e A N NE Prescott St e A v N Prescott St e NE Prescott St y E E E v h N Skidmore Ct e t l v A t l NE 25th Ave NE 25th s v N N e G A N A 6 e e h u 1 v A t v v 2 d NE Campaign St l NE 27th Ave -

Sub-Area: Northeast

PARKS 2020 VISION N ORTHEAST Distinctive Features I The18-hole Rose City Golf Course is in the southeast corner of the sub-area. Description: The Northeast sub-area (see map at the end I The Roseway Parkway, a major feature in the of this section) is characterized by established neighbor- Roseway neighborhood, provides visual access hoods with pockets and corridors of higher-density and to the Columbia River. new development. This sub-area does not include the I Lloyd District, nor the east bank of the Willamette River, Major trails include the I-205 Bikeway and the which are included in the Central City/Northwest sub-area. Marine Drive and Columbia Slough sections of the 40-Mile Loop Trail. Resources and Facilities: There are 508 acres of park land in Northeast, placing this sub-area last among the Population – Current and Future: The Northeast sub-areas with the least amount of park acreage. sub-area ranks third in population with 103,800 and Although there are a relatively large number (twenty-six) is projected to grow to 109,270 in 2020, an increase of neighborhood and community parks, their combined of 5%. acreage is only 191 acres. I Natural resource areas in this area include Rocky Butte, Johnson Lake, Whitaker Ponds and about DISTRIBUTION OF SUBAREA ACRES BY PARK TYPE seven miles of the Columbia Slough, all on the edges of the sub-area. The central part of the sub-area contains very few natural resource areas. I East Delta Park includes major sports facilities with Strasser Field/ Stadium, eight other soccer fields, the five-field William V. -

Oregon State Parks

iocuN OR I Hi ,tP7x OREGON STATE PARKS HISTORY 1917-1963 \STATE/ COMPILED by CHESTER H. ARMSTRONG JULY I. 1965 The actual date of the i is less than thirty years ag older, supported by a few o were an innovation as so lit The Oregon parks system o beautification advocated b: Governors, the early State ] neers. The records reveal out areas, made favorable were generous with their Roy A. Klein, State Highk& ary 29, 1932, as a leader wl The state parks system thought of highway beauti many highway users who h who could not well afford t] In the park story we fii the many influential people complete, it is necessary to thought or trend in the idea the thought of highway be, may see and follow the trai present state narks system. In the preparation of th $ been examined. It was neck ing to property acquisitions deeds and agreements. as tln records of the Parks Divisik Excellent information h; State Parks and Recreatioi A Public Relations Office. As many etbers. I Preface The actual date of the founding of the Oregon State Parks System is less than thirty years ago but the fundamental principles are much older, supported by a few of the leading park people of that time. They were an innovation as so little had been done by any state in the Union. The Oregon parks system owes its beginning to the thought of highway beautification advocated by many leaders of the state, including the Governors, the early State Highway Commissioners and Highway Engi- neers. -

The Sullivan's Gulch Trail Study

THE SULLIVAN’S GULCH TRAIL STUDY Master of Urban and Regional Planning Workshop Project Portland State University June 2004 THE SULLIVAN’S GULCH TRAIL STUDY Michael Hoffmann Darren Muldoon Joseph Schaefer Morgan Will Master of Urban and Regional Planning Program College of Urban and Public Affairs Portland State University Planning Workshop June 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMETS Portland State University Metro City of Portland Professors Parks and Greenspaces Bureau of Environmental Services Dr. Ethan Seltzer Mel Huie, Senior Regional Planner Mark Liebe Dr. Deborah Howe Mary West, Co‐Volunteer Manager Andrey Nkolayev, Mapping Intern Dr. Barry Messer Dr. Robert Bertini Planning Office of Transportation Bill Barber, Regional Travel Options Program/ Courtney Duke, Pedestrian Coordinator Engineering Study Student Groups Bicycle Planning Coordination Roger Geller, Bicycle Coordinator Section 1: Kim Ellis, Regional Transportation Planning/ Mike Beye Pedestrian Planning Coordination Parks and Recreation Salina Bird Jim Sjulin, Natural Resources Michelle Degano Data Resource Center Janet Bebb, Planning and Development Tina Lundell Mark Bosworth, Senior GIS Specialist Gregg Everhart, Planning and Development Danae McQuinn Metro Councilors Section 2: David Bragdon, President Neighborhood and Business Associations Wade Ansell Rex Burkholder, District 5 Gateway Area Business Association Andrey Nkolayev Rod Monroe, District 6 Montavilla Community Association Kaha’a Rezantes Grant Park Neighborhood Association Erik Wahrgren Volunteer Sullivan’s Gulch Neighborhood Association Jeff Hansen *Thanks to Dave Brook for the web survey Section 3: Lloyd District Transportation Management River Hwang Thareth Yin Alta Planning + Design Jeff Chin Mia Birk, Principal Section 4: ABOUT PLANNING WORKSHOP Jeremy Brewster Mike Lundervold Planning Workshop, the capstone course for Portland State University’s Master of Urban and Jeremy Parrish Regional Planning Program, provides graduate students with professional planning experience. -

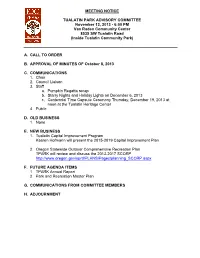

A. CALL to ORDER B. APPROVAL of MINUTES of October 8, 2013 C

MEETING NOTICE TUALATIN PARK ADVISORY COMMITTEE November 12, 2013 - 6:00 PM Van Raden Community Center 8535 SW Tualatin Road (Inside Tualatin Community Park) A. CALL TO ORDER B. APPROVAL OF MINUTES OF October 8, 2013 C. COMMUNICATIONS 1. Chair 2. Council Liaison 3. Staff a. Pumpkin Regatta recap b. Starry Nights and Holiday Lights on December 6, 2013 c. Centennial Time Capsule Ceremony Thursday, December 19, 2013 at noon at the Tualatin Heritage Center 4. Public D. OLD BUSINESS 1. None E. NEW BUSINESS 1. Tualatin Capital Improvement Program Kaaren Hofmann will present the 2015-2019 Capital Improvement Plan 2. Oregon Statewide Outdoor Comprehensive Recreation Plan TPARK will review and discuss the 2013-2017 SCORP http://www.oregon.gov/oprd/PLANS/Pages/planning_SCORP.aspx F. FUTURE AGENDA ITEMS 1. TPARK Annual Report 2. Park and Recreation Master Plan G. COMMUNICATIONS FROM COMMITTEE MEMBERS H. ADJOURNMENT City of Tualatin DRAFT TUALATIN PARK ADVISORY COMMITTEE MINUTES October 8, 2013 MEMBERS PRESENT: Dennis Wells, Valerie Pratt, Kay Dix, Stephen Ricker, Connie Ledbetter MEMBERS ABSENT: Bruce Andrus-Hughes, Dana Paulino, STAFF PRESENT: Carl Switzer, Parks and Recreation Manager PUBLIC PRESENT: None OTHER: None A. CALL TO ORDER Meeting called to order at 6:06. B. APPROVAL OF MINUTES The August 13, 2013 minutes were unanimously approved. C. COMMUNICATIONS 1. Public – None 2. Chairperson – None 3. Staff – Staff presented an update to the 10th Annual West Coast Giant Pumpkin Regatta. Stephen said he would like to race again. TPARK was invited to attend the special advisory committee meeting about Seneca Street extension. TPARK was informed that the CDBG grant application for a new fire sprinkler system for the Juanita Pohl Center was submitted. -

City Club of Portland Report: Portland Metropolitan Area Parks

Portland State University PDXScholar City Club of Portland Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library 9-23-1994 City Club of Portland Report: Portland Metropolitan Area Parks City Club of Portland (Portland, Or.) Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityclub Part of the Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation City Club of Portland (Portland, Or.), "City Club of Portland Report: Portland Metropolitan Area Parks" (1994). City Club of Portland. 470. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityclub/470 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in City Club of Portland by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. CITY CLUB OF PORTLAND REPORT Portland Metropolitan Area Parks Published in City Club of Portland Bulletin Vol. 76, No. 17 September 23,1994 CITY CLUB OF PORTLAND The City Club membership will vote on this report on Friday September 23, 1994. Until the membership vote, the City Club of Portland does not have an official position on this report. The outcome of this vote will be reported in the City Club Bulletin dated October 7,1994. (Vol. 76, No. 19) CITY CLUB OF PORTLAND BULLETIN 93 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 96 II. A VISION FOR PORTLAND AREA PARKS 98 A. Physical Aspects 98 B. Organizational Aspects 98 C. Programmatic Aspects 99 III. INTRODUCTION 99 IV. BACKGROUND 100 A. -

Ordinance Amending County Land Use Code to Adopt

BEFORE THE BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS FOR MULTNOMAH COUNTY, OREGON ORDINANCE NO. 1212 Amending County Land Use Code to Adopt Portland's Willamette River Greenway Inventory and Declaring an Emergency. The Multnomah County Board of Commissioners Finds: a. The Board of County Commissioners (Board) adopted Resolution A in 1983 which directed the County services towards rural services rather than urban. b. In 1996, Metro adopted the Functional Plan for the region, mandating that jurisdictions comply with the goals and policies adopted by the Metro Council. c. In 1998, the County and the City of Portland (City) amended the Urban Planning Area Agreement to include an agreement that the City would provide planning services to achieve compliance with the Functional Plan for those areas outside the City limits, but within the Urban Growth Boundary and Portland's Urban Services Boundary. d. It is impracticable to have the County Planning Commission conduct hearings and make recommendations on land use legislative actions pursuant to MCC 37.0710, within unincorporated areas inside the Urban Growth Boundary for which the City provides urban planning and permitting services. The Board intends to exempt these areas from the requirements of MCC 37.0710, and will instead consider the recommendations of the Portland Planning Commission and City Council when legislative matters for these areas are brought before the Board for action as required by intergovernmental agreement (County Contract #4600002792) (IGA). e. On September 4, 2014, the Board amended County land use codes, plans and maps to adopt the City's land use codes, plans and map amendments in compliance with Metro's Functional Plan by Ordinance 1209. -

OREGON PARKS and RECREATION COMMISSION June 12 & 13, 2018

OREGON PARKS AND RECREATION COMMISSION June 12 & 13, 2018 Harney County Chamber of Commerce 484 N Broadway Ave Burns, OR 97720 DRAFT MINUTES Tuesday, June 12, 2018 - Location: Frenchglen, Oregon WORK-SESSION / TRAINING: 7:30am Budget preliminary revenues, expenditures, cash flow, and policy package TOUR: 8:30am Steens Mountain, BLM Campgrounds, Peter French Round Barn COMMUNITY OPEN HOUSE: 3:00pm – 5:00pm Wednesday, June 13, 2018 - Location: Harney County Chamber of Commerce EXECUTIVE SESSION: 8:15am The Commission met in Executive Session to discuss acquisition priorities and opportunities, and potential litigation. The Executive Session will be held pursuant to ORS 192.660(2) (e) and (h), and is closed to the public. BUSINESS MEETING: 9:30am • Cal Mukumoto, Commission Chair • MG Devereux, OPRD Deputy Director • Jennifer H. Allen, Commission Vice-Chair • Denise Warburton, OPRD • Lisa Dawson, Commission • Chris Havel, OPRD • Jonathan Blasher, Commission • Tanya Crane, OPRD • Doug Deur – Commission • Tracy Louden, OPRD • Vicki Berger, Commission • Kammie Bunes, OPRD • Steve Grasty, Commission • Chas Vangenderen, OPRD • Steve Shipsey, Counsel for Commission, DOJ • Scott Nebeker, OPRD • Lisa Sumption, OPRD Director 1. Commission Business: a) Welcome and Introductions b) Director Appointment OPRD Commission Minutes June 12 & 13, 2018 Page 1 of 4 ACTION: Commissioner Allen moved to approve reappointing Director Lisa Sumption. Commissioner Berger seconded. The motion passed, 7-0. (Topic starts 00:05:26 and ends 00:07:06) c) Approval of November 2017 Minutes ACTION: Commissioner Berger moved to approve the April 2018 minutes with the correction of attendance. Commissioner Grasty seconded. The motion passed 7-0. (Topic starts 00:08:23 and ends 00:09:42) d) Approval of February 2018 Agenda Action: Commissioner Grasty moved to approve the June agenda. -

Portland Urban Area

Shillapoo PortlandWildlife Area Urban Area Map Mud Slough UV99 Amtrak CascadesShillapoo WildlifeRoute Area nn Bell View Point 99 Gilbert River UV WA-500Legend E Spring Branch NE St Johns Rd Enlarged 500 County Line NEAndresen Rd UV E 39th St Area Howell Vancouver Station WA-500 W Urban Growth Boundary Territorial Multnomah Channel Kelley Point Park WA-500 Burlington Park WA-500 City Limit Bottoms 500 NE 162ndAve UV NE Fourth Plain Rd US Census Tracts where Proportion of Low-Income Existing Rail Crossing or Minority Population is more than twice the State ¨¦§5 E Fourth Plain Blvd OREGON at Columbia River Average Burnt Bridge Creek Parks and Open Spaces NE 162ndAve Main St UV501 205 City of Portland Historic Districts NEAndresen Rd ¨¦§ E Mill Plain Blvd Wetland Priority Sites NE 164th Ave E Mill Plain Blvd ¤£30 Fort Vancouver Wetlands National Historic Site !!! Federally Designated Critical Habitat SE Mill Plain Blvd Ennis Creek SE 1st St (Linear Feature) NE 192ndAve Smith and Bybee SE Mill Plain Blvd Wetlands Natural Area 14 UV Water Bodies N Marine Dr Columbia River Rivers/Streams S Lieser Rd Chimney Park Miller Creek Lotus Isle Park Existing Railroads Forest Park Heron Lakes High Volume At-Grade Railroad Crossing SE 192ndAve Pier Park Golf Course UV14 !? (Road Traffic >15,000 AADT) n SE 164thAve NE Martin Luther King Jr Blvd N Portland Rd M James Gleason Memorial Boat Ramp v® Hospitals n Wright Island Columbia Slough #1 Columbia WA-14 W St Johns Park George Park Exeter Property Children's n Schools N Columbia Blvd Arboretum WA-14 E Cathedral -

FINAL REPORT 20S N-S BIKEWAY

FINAL REPORT 20s N-S BIKEWAY NE GLISAN - SE BELMONT brian emerson sravya garladenne brenda martin melissa mohr AIRWAY Kenton Park GRAND Farragut Park TERRY AIRPORT PERIMETER 11TH DENVER FENWICK S AIRTRANS De La Salle North Catholic High School 33RD HANIS RUSSET FOS H Columbia South Shore Trail TH 8 10T STATE A STAFFORD C Broadmoor Golf Course SHILLING AR Colwood National Golf Course Gammans Park HOLLAND ARG L I5 YLE D WILLIAMS LOMBARD JOHNSON INTER VANCOUVER N ALBIN MORGAN Woodlawn ES 2 BUFFALO BRYANT 4 SKYPORT Arbor Lodge Park Woodlawn Park H CORNFOOT SARATOGA BRYANT DEKUM 29T 79TH Whitaker Ponds Nature Park Holy Redeemer ES WILBUR Peninsula Park Community Center Faubian SUN Community School Whitaker Lakeside MS Concordia College H H 66TH Peninsula Pool H H HIGHLAND 2ND 45TH 6T 8T NE Holman and 13th 27TH COLUMB 8 HOLMAN H GARFIELD 10T PORTLAND 30TH 35T DELAWARE Ockley Green MS IA T 9TH AINSWORTH 78 4 TH MONTANA MISSOURI MICHIGAN MOORE Fernhill Park SIMPSON HAIGHT PARK 0 N Omaha Parkway 8 TH Alberta CULLY JESSUP 15TH 18 9TH 25TH 12TH Park JARRETT SIMPSON Kennedy Community Garden 60TH KILLINGS 48TH H W H Interstate Firehouse Cultural Center ORTH CHURCH Jefferson High School 24T Thomas Cully Property 26T Patton Square Park 32ND TH14 Vernon ES Cully Community Garden 45TH N 49TH EMERSO 47TH Roselawn Park 54TH Sumner-Albina Park 52ND EMERSON Helensview HS SUMNER H Patton Community Garden ALBERTA 29TH ROSELAWN Beach ES Meek ES 35T 14TH Sacajawea Park H Werbin Property Common Bond Garden H NE Sumner & 47th H Beach Community Garden 6TH 9TH Sacajawea -

Outdoor Recreation in Oregon: Responding to Demographic and Societal Change

Outdoor Recreation in Oregon: Responding to Demographic and Societal Change 2019-2023 Oregon Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan Oregon Parks and Recreation Department This document is part of the Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) process. Authority to conduct the SCORP process is granted to the Director of the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department under Oregon Revised Statute (ORS) 390.180. The preparation of this plan was financed, in part, through a Land and Water Conservation Fund planning grant, and the plan was approved by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior under the provisions for the Federal Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 (Public Law 188-578). Foreward A message from the Director, Oregon Parks and Recreation Department The Oregon Parks and Recreation Department (OPRD) is pleased to provide your organization with a copy of the 2019-2023 Oregon Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) entitled Outdoor Recreation in Oregon: Responding to Demographic and Societal Change. This plan focuses on a number of serious challenges facing the wellbeing our state, our local communities, and our parks and natural resources. These challenges are associated with shifting demographics and lifestyle changes which are resulting in a clientele base with needs different from those served by recreation (LWCF) program and other OPRD-administered providers in the past. grant programs including the Local Grant, County Opportunity Grant, Recreational Trails This plan closely examines the effects of an aging and All-Terrain Vehicle programs. OPRD will population, an increasingly diverse population, support the implementation of key statewide lack of youth engagement in outdoor recreation, and local planning recommendations through an underserved low-income population, and internal and external partnerships and OPRD- increasing levels of physical inactivity within administered grant programs.