Food Composition and Production in Medieval England and Their Mutual Influences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Igbo Traditional Food System Documented in Four States in Southern Nigeria

Chapter 12 The Igbo traditional food system documented in four states in southern Nigeria . ELIZABETH C. OKEKE, PH.D.1 . HENRIETTA N. ENE-OBONG, PH.D.1 . ANTHONIA O. UZUEGBUNAM, PH.D.2 . ALFRED OZIOKO3,4. SIMON I. UMEH5 . NNAEMEKA CHUKWUONE6 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems 251 Study Area Igboland Area States Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State Ubulu-Uku/Alumu in Delta State Lagos Nigeria Figure 12.1 Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State Ede-Oballa/Ukehe IGBO TERRITORY in Enugu State Participating Communities Data from ESRI Global GIS, 2006. Walter Hitschfield Geographic Information Centre, McGill University Library. 1 Department of 3 Home Science, Bioresources Development 5 Nutrition and Dietetics, and Conservation Department of University of Nigeria, Program, UNN, Crop Science, UNN, Nsukka (UNN), Nigeria Nigeria Nigeria 4 6 2 International Centre Centre for Rural Social Science Unit, School for Ethnomedicine and Development and of General Studies, UNN, Drug Discovery, Cooperatives, UNN, Nigeria Nsukka, Nigeria Nigeria Photographic section >> XXXVI 252 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems | Igbo “Ndi mba ozo na-azu na-anwu n’aguu.” “People who depend on foreign food eventually die of hunger.” Igbo saying Abstract Introduction Traditional food systems play significant roles in maintaining the well-being and health of Indigenous Peoples. Yet, evidence Overall description of research area abounds showing that the traditional food base and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples are being eroded. This has resulted in the use of fewer species, decreased dietary diversity due wo communities were randomly to household food insecurity and consequently poor health sampled in each of four states: status. A documentation of the traditional food system of the Igbo culture area of Nigeria included food uses, nutritional Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State, value and contribution to nutrient intake, and was conducted Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State, in four randomly selected states in which the Igbo reside. -

Consumer Trends Bakery Products in Canada

International Markets Bureau MARKET INDICATOR REPORT | JANUARY 2013 Consumer Trends Bakery Products in Canada Source: Shutterstock Consumer Trends Bakery Products in Canada MARKET SNAPSHOT INSIDE THIS ISSUE The bakery market in Canada, including frozen bakery and Market Snapshot 2 desserts, registered total value sales of C$8.6 billion and total volume sales of 1.2 million tonnes in 2011. The bakery Retail Sales 3 category was the second-largest segment in the total packaged food market in Canada, representing 17.6% of value sales in 2011. However, the proportional sales of this Market Share by Company 6 category, relative to other sub-categories, experienced a slight decline in each year over the 2006-2011 period. New Bakery Product 7 Launches The Canadian bakery market saw fair value growth from 2006 to 2011, but volume growth was rather stagnant. In New Bakery Product 10 addition, some sub-categories, such as sweet biscuits, Examples experienced negative volume growth during the 2006-2011 period. This stagnant volume growth is expected to continue over the 2011-2016 period. New Frozen Bakery and 12 Dessert Product Launches According to Euromonitor (2011), value growth during the 2011-2016 period will likely be generated from increasing New Frozen Bakery and 14 sales of high-value bakery products that offer nutritional Dessert Product Examples benefits. Unit prices are expected to be stable for this period, despite rising wheat prices. Sources 16 Innovation in the bakery market has become an important sales driver in recent years, particularly for packaged/ Annex: Definitions 16 industrial bread, due to the increasing demand for bakery products suitable for specific dietary needs, such as gluten-free (Euromonitor, 2011). -

Alkaline Foods...Acidic Foods

...ALKALINE FOODS... ...ACIDIC FOODS... ALKALIZING ACIDIFYING VEGETABLES VEGETABLES Alfalfa Corn Barley Grass Lentils Beets Olives Beet Greens Winter Squash Broccoli Cabbage ACIDIFYING Carrot FRUITS Cauliflower Blueberries Celery Canned or Glazed Fruits Chard Greens Cranberries Chlorella Currants Collard Greens Plums** Cucumber Prunes** Dandelions Dulce ACIDIFYING Edible Flowers GRAINS, GRAIN PRODUCTS Eggplant Amaranth Fermented Veggies Barley Garlic Bran, wheat Green Beans Bran, oat Green Peas Corn Kale Cornstarch Kohlrabi Hemp Seed Flour Lettuce Kamut Mushrooms Oats (rolled) Mustard Greens Oatmeal Nightshade Veggies Quinoa Onions Rice (all) Parsnips (high glycemic) Rice Cakes Peas Rye Peppers Spelt Pumpkin Wheat Radishes Wheat Germ Rutabaga Noodles Sea Veggies Macaroni Spinach, green Spaghetti Spirulina Bread Sprouts Crackers, soda Sweet Potatoes Flour, white Tomatoes Flour, wheat Watercress Wheat Grass ACIDIFYING Wild Greens BEANS & LEGUMES Black Beans ALKALIZING Chick Peas ORIENTAL VEGETABLES Green Peas Maitake Kidney Beans Daikon Lentils Dandelion Root Pinto Beans Shitake Red Beans Kombu Soy Beans Reishi Soy Milk Nori White Beans Umeboshi Rice Milk Wakame Almond Milk ALKALIZING ACIDIFYING FRUITS DAIRY Apple Butter Apricot Cheese Avocado Cheese, Processed Banana (high glycemic) Ice Cream Berries Ice Milk Blackberries Cantaloupe ACIDIFYING Cherries, sour NUTS & BUTTERS Coconut, fresh Cashews Currants Legumes Dates, dried Peanuts Figs, dried Peanut Butter Grapes Pecans Grapefruit Tahini Honeydew Melon Walnuts Lemon Lime ACIDIFYING Muskmelons -

Fatty Liver Diet Guidelines

Fatty Liver Diet Guidelines What is Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)? NAFLD is the buildup of fat in the liver in people who drink little or no alcohol. NAFLD can lead to NASH (Non- Alcoholic Steatohepatitis) where fat deposits can cause inflammation and damage to the liver. NASH can progress to cirrhosis (end-stage liver disease). Treatment for NAFLD • Weight loss o Weight loss is the most important change you can make to reduce fat in the liver o A 500 calorie deficit/day is recommended or a total weight loss of 7-10% of your body weight o A healthy rate of weight loss is 1-2 pounds/week • Change your eating habits o Avoid sugar and limit starchy foods (bread, pasta, rice, potatoes) o Reduce your intake of saturated and trans fats o Avoid high fructose corn syrup containing foods and beverages o Avoid alcohol o Increase your dietary fiber intake • Exercise more o Moderate aerobic exercise for at least 20-30 minutes/day (i.e. brisk walking or stationary bike) o Resistance or strength training at least 2-3 days/week Diet Basics: • Eat 3-4 times daily. Do not go more than 3-4 hours without eating. • Consume whole foods: meat, vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds, legumes, and whole grains. • Avoid sugar-sweetened beverages, added sugars, processed meats, refined grains, hydrogenated oils, and other highly processed foods. • Never eat carbohydrate foods alone. • Include a balance of healthy fat, protein, and carbohydrate each time you eat. © 7/2019 MNGI Digestive Health Healthy Eating for NAFLD A healthy meal includes a balance of protein, healthy fat, and complex carbohydrate every time you eat. -

Wic Approved Food Guide

MASSACHUSETTS WIC APPROVED FOOD GUIDE GOOD FOOD and A WHOLE LOT MORE! June 2021 Shopping with your WIC Card • Buy what you need. You do not have to buy all your foods at one time! • Have your card ready at check out. • Before scanning any of your foods, tell the cashier you are using a WIC Card. • When the cashier tells you, slide your WIC Card in the Point of Sale (POS) machine or hand your WIC Card to the cashier. • Enter your PIN and press the enter button on the keypad. • The cashier will scan your foods. • The amount of approved food items and dollar amount of fruits and vegetables you purchase will be deducted from your WIC account. • The cashier will give you a receipt which shows your remaining benefit balance and the date benefits expire. Save this receipt for future reference. • It’s important to swipe your WIC Card before any other forms of payment. Any remaining balance can be paid with either cash, EBT, SNAP, or other form of payment accepted by the store. Table of Contents Fruits and Vegetables 1-2 Whole Grains 3-7 Whole Wheat Pasta Bread Tortillas Brown Rice Oatmeal Dairy 8-12 Milk Cheese Tofu Yogurt Eggs Soymilk Peanut Butter and Beans 13-14 Peanut Butter Dried Beans, Lentils, and Peas Canned Beans Cereal 15-20 Hot Cereal Cold Cereal Juice 21-24 Bottled Juice - Shelf Stable Frozen Juice Infant Foods 25-27 Infant Fruits and Vegetables Infant Cereal Infant Formula For Fully Breastfeeding Moms and Babies Only (Infant Meats, Canned Fish) 1 Fruits and Vegetables Fruits and Vegetables Fresh WIC-Approved • Any size • Organic allowed • Whole, cut, bagged or packaged Do not buy • Added sugars, fats and oils • Salad kits or party trays • Salad bar items with added food items (dip, dressing, nuts, etc.) • Dried fruits or vegetables • Fruit baskets • Herbs or spices Any size Any brand • Any fruit or vegetable Shopping tip The availability of fresh produce varies by season. -

Recent Trends in Jewish Food History Writing

–8– “Bread from Heaven, Bread from the Earth”: Recent Trends in Jewish Food History Writing Jonathan Brumberg-Kraus Over the last thirty years, Jewish studies scholars have turned increasing attention to food and meals in Jewish culture. These studies fall more or less into two different camps: (1) text-centered studies that focus on the authors’ idealized, often prescrip- tive construction of the meaning of food and Jewish meals, such as biblical and postbiblical dietary rules, the Passover Seder, or food in Jewish mysticism—“bread from heaven”—and (2) studies of the “performance” of Jewish meals, particularly in the modern period, which often focus on regional variations, acculturation, and assimilation—“bread from the earth.”1 This breakdown represents a more general methodological split that often divides Jewish studies departments into two camps, the text scholars and the sociologists. However, there is a growing effort to bridge that gap, particularly in the most recent studies of Jewish food and meals.2 The major insight of all of these studies is the persistent connection between eating and Jewish identity in all its various manifestations. Jews are what they eat. While recent Jewish food scholarship frequently draws on anthropological, so- ciological, and cultural historical studies of food,3 Jewish food scholars’ conver- sations with general food studies have been somewhat one-sided. Several factors account for this. First, a disproportionate number of Jewish food scholars (compared to other food historians) have backgrounds in the modern academic study of religion or rabbinical training, which affects the focus and agenda of Jewish food history. At the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, my background in religious studies makes me an anomaly. -

From-Pottage-To-Peacock.Pdf

2 From Pottage to Peacock: A Guide to Medieval Food Nicol Valentin Historyunfettered.com 3 4 In the beginning . There was food, and the food was tasty. Wine from Palestine, olive oil from Spain, tableware from Gaul: these were the things coming into Britain before the fall of Rome. In fact, thanks to the Romans, the British were introduced to a large selection of vegetables like garlic, onions, leeks, cabbages, turnips, asparagus, and those beloved peas. Spices like pepper, nutmeg, and ginger were introduced too. Things were grand, and then in 410 the Romans left. The world became fragmented. Towns disappeared, villas were abandoned, and society was in the midst of catastrophic collapse. No one had time to worry about imported wine or fancy spices. Slowly, however, pockets of stability returned. Chaos turned to order, and someone said, !I think it"s time for a really great dinner.# 5 First, the Bad Stuff ! Unfortunately, food was never a certainty in the medieval world. Starvation was always a possibility, no matter who you were. Crops failed, fields flooded, animals caught diseases, and any of these things could leave your table empty. Sometimes you got hit with more than one calamity. Even in the best conditions, you could still starve. If you found yourself in a town under siege, your choices were to surrender to a quick death by hanging or a slow one by starvation. Neither seems very appealing. If the crops were good and no one was knocking down your door with sword and ax, there was still more to watch out for. -

A Taste of Scotland?

A TASTE OF SCOTLAND?: REPRESENTING AND CONTESTING SCOTTISHNESS IN EXPRESSIVE CULTURE ABOUT HAGGIS by © Joy Fraser A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Folklore Memorial University of Newfoundland October 2011 St. John's Newfoundland Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-81991-3 Our file Notre r6ference ISBN: 978-0-494-81991-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Medieval Cuisine

MEDIEVAL CUISINE Food as a Cultural Identity CHRISTOPHER MACMAHON CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY CHANNEL ISLANDS When reflecting upon the Middle Ages, there are many views that might come to one’s mind. One may think of Christian writings or holy warriors on crusade. Perhaps another might envision knights bedecked in heavy armor seeking honorable combat or perhaps an image of cities devastated by plague. Yet few would think of the Middle Ages in terms of cuisine. Cuisine in this time period can be approached in a variety of ways, but for many, the mere mention of food would provoke images of opulent feasts, of foods of luxury. David Waines takes this approach when looking at how medieval Islamic societies approached the idea of luxury foods. Waines begins with the idea invoked above, that a luxury food was one which was “expensive, pleasurable and unnecessary.”1 But, Waines goes on to ask, could not luxury also be considered a dish, no matter how humble the origin, whose preparation was so exquisite that it was beyond compare?2 While challenging the traditional thinking in regards to how one views cuisine, it must be noted that Waines’ focus is upon luxury foods. Whether prohibitively expensive or expertly prepared, such dishes would only be available to a very select elite. Another common method for looking at the role food played in medieval life is to look at the relationship between food and the economy. This relationship occurred in both local and international trade. Derek Keene investigates how cities “profoundly influenced the economies… of their hinterlands” by examining the relationship between the city of London and the area surrounding the city.3 Keene demonstrates that a network of ringed zones worked outward from the city, each with a specific support function. -

Cinnamon Bread Breakfast Sandwich Recipe

Published on Swaggerty's Farm (https://www.swaggertys.com) Home > Cinnamon Bread Breakfast Sandwich Recipe This breakfast sandwich recipe is so delicious & easy you may wonder why you never thought of it. Eggs & hash brown potatoes, covered with melted cheese & topped with slices of hot sausage, sandwiched between hot toasted, straight from the oven cinnamon bread. Drizzle with maple syrup! Bam! PDF [1] PRINT [1] SHARE Cinnamon Bread Breakfast Sandwich Recipe Directions 1. Preheat oven to 375 degrees. 2. Smear slices of Cinnamon Swirl bread on both sides with softened butter. Lay slices out flat on a baking sheet. Set aside. 3. Whisk together the eggs and a pinch of salt & black pepper. 4. Stir the shredded potatoes into the eggs. 5. Scoop egg-potato mixture into a hot skillet with melted butter to create 4 patties. Cook on both sides until crisp. 6. Put pan with bread slices into the oven to lightly toast. 7. When egg-potato patties are done immediately top with slices of cheddar cheese. Set aside. 8. Remove lightly toasted bread from the oven. 9. To assemble sandwiches: lay four slices of bread on flat work surface. Top each slice of bread with one of the egg-potato-melted cheese patties. Place two Swaggerty’s sausage patties on each and top with 2nd slice of toasted Cinnamon Bread. 10. Serve warm as a handheld sandwich or plated with a drizzle of maple syrup. To Serve This breakfast sandwich has it all….eggs, potatoes, cheese, Swaggerty’s Farm Sausage & wonderfully toasted Cinnamon Bread. 4 servings 15 min prep time 10 min cook time -

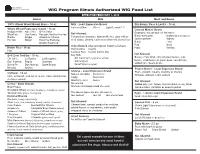

WIC Program Illinois Authorized WIC Food List

State of Illinois Department of Human Services WIC Program Illinois Authorized WIC Food List EFFECTIVE FEBRUARY 1, 2019 Grains Milk Meat and Beans 100% Whole Wheat Bread, Buns - 16 oz Milk - Least Expensive Brand Dry Beans, Peas & Lentils - 16 oz Fat Free/Skim Whole Light/Lowfat/1% Whole Wheat Pasta (any shape) - 16 oz Canned Mature Beans Hodgson Mill Racconto Great Value Examples include but not limited to: ShurFine Our Family Ronzoni Healthy Harvest Not Allowed: Black-eyed peas Garbanzo (chickpeas) Barilla Kroger America’s Choice Flavored or chocolate, buttermilk, rice, goat milk or Hy-Vee Meijer Essential Everyday shelf stable, almond, cashew or other milk alternatives Great northern Kidney Simply Balanced Black Lima Only Allowed when printed on Food Instrument: Red Navy Brown Rice - 16 oz Half Gallons Quarts Pinto Refried Plain Lactose Free Instant Nonfat Dry Not Allowed: Soft Corn Tortillas - 16 oz Soy Milk Soups of any kind, canned green beans, wax Chi Chi’s La Burrita La Banderita 8th Continent (original or vanilla) beans, snap beans or green peas, seasonings, Don Pancho Pepito Guerrero Silk (original) added fats, meats or oils Santa Fe Don Marcos Store Brand Great Value (original) Mission Azteca Peanut Butter - Least Expensive Brand Cheese - Least Expensive Brand Oatmeal - 16 oz Plain, smooth, creamy, crunchy or chunky Natural Cheddar Provolone All types allowed in low sodium Old Fashioned, Traditional, Quick-Cook, Rolled Oats Colby Muenster (no flavors added) Monterey Jack Swiss Not Allowed: Cereal - Store Brands Mozzarella Added -

Read Book Soups : 120 Delicious Recipes from Cuisine Et Vins De

SOUPS : 120 DELICIOUS RECIPES FROM CUISINE ET VINS DE FRANCE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cuisine et Vins de France | 192 pages | 11 Feb 2016 | Whitecap Books | 9781770503090 | English | United States Soups : 120 Delicious Recipes from Cuisine Et Vins de France PDF Book Pureeing equipment. Cox assistant , Daniel J. Btw, you have a strong resemblance with Angelina Jolie. A broth makes a delicious soup in its own right and it can also be used as the moistening agent in other soups. Vegetable soups, in particular, are the victims of unnecessary refinements; the traditional belief that vegetables should be precooked in fat and simmered in beef broth has been responsible for masking and altering many a fresh garden flavor. Keep up the good works! Traditional cherry clafoutis was made using unpitted cherries, which supposedly added a flavour to the dish reminiscent of almonds. Spoon the mixture into a pastry bag equipped with a small tube o r, as shown, into a cone made by rolling a sheet of parchment paper and cutting off the tip. Flaherty Jr. The same principles apply to garnishes. I made the carrot and ginger soup last night. Lifting the egg sacs out of a mullet in one piece without tearing the fragile membrane requires the hands of a surgeon. Bonjour Marie! Facebook Pinterest Instagram. October 17, at pm. Cream soups are simply purees with cream added; if the main ingredient is shellfish, however, such a soup may be called a bisque-a term that was originally applied to game and poultry soups in addition to those made from shellfish.