You Are What You Ate Medieval Food and Bioarchaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

Cutlery CUTLERY Contents

Cutlery CUTLERY Contents Folio 6 Whitfield ............................. 8 Carolyn .............................. 9 Logan ................................. 9 Hartman ............................. 11 Alison ................................. 12 Bryce .................................. 15 Pirouette ............................. 15 Varick 14 Avery .................................. 16 Estate ................................. 17 Marnee............................... 18 Avina .................................. 19 Distressed Briar ................... 20 Fulton Vintage Copper ......... 21 Fulton Vintage ..................... 22 Origin ................................ 23 Steak Knives ........................ 24 Jean Dubost 26 Laguiole ............................. 26 Hepp 28 Mescana ............................. 30 Trend .................................. 31 Aura ................................... 31 Ecco ................................... 32 Talia ................................... 33 Baguette ............................. 34 Profile ................................. 35 Elia 36 Spirit .................................. 38 Tempo ................................ 39 Ovation .............................. 40 Miravell .............................. 41 Features & Benefits ...... 42 Care Guidelines ............ 43 2 CUTLERY 3 CUTLERY Cutlery The right cutlery can bring a whole new dimension to your tabletop. With Folio, Varick, Laguiole, HEPP and Elia our specialist partners, we have designers of fine cutlery who perfectly mirror our own exacting -

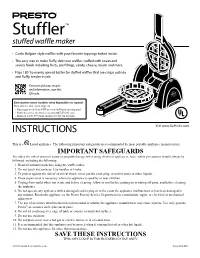

Stuffler™ Stuffed Waffle Maker

Stuffler™ stuffed waffle maker • Cooks Belgian-style waffles with your favorite toppings baked inside. • The easy way to make fluffy, delicious waffles stuffed with sweet and savory foods including fruits, pie fillings, candy, cheese, meats and more. • Flips 180° to evenly spread batter for stuffed waffles that are crispy outside and fluffy, tender inside. For more delicious recipes and information, scan this QR code. Estas instrucciones también están disponibles en español. Para obtener una copia impresa: • Descargue en formato PDF en www.GoPresto.com/espanol. • Envíe un correo electrónico a [email protected]. • Llame al 1-800-877-0441, oprima 2 y deje un mensaje. INSTRUCTIONS Visit www.GoPresto.com This is a Listed appliance. The following important safeguards are recommended by most portable appliance manufacturers. IMPORTANT SAFEGUARDS To reduce the risk of personal injury or property damage when using electrical appliances, basic safety precautions should always be followed, including the following: 1. Read all instructions before using the waffle maker. 2. Do not touch hot surfaces. Use handles or knobs. 3. To protect against the risk of electrical shock, never put the cord, plug, or unit in water or other liquids. 4. Close supervision is necessary when any appliance is used by or near children. 5. Unplug from outlet when not in use and before cleaning. Allow to cool before putting on or taking off parts, and before cleaning the appliance. 6. Do not operate any appliance with a damaged cord or plug or in the event the appliance malfunctions or has been damaged in any manner. Return the appliance to the Presto Factory Service Department for examination, repair, or electrical or mechanical adjustment. -

Halušky with Sauerkraut

Halušky with Sauerkraut 4 servings Active Time: 35 min. Total Time: 35 min. Level of Advancement: 1/5 Halušky are most likely the easiest pasta meal made from scratch. It is superfast and at the same time, super tasty. Halušky are a traditional Slovak Shepherd’s meal. Ingredients: Halušky batter: 2 LB of potatoes 1 large egg ½ TSP of salt 2 ½ cups of all-purpose flour Sauerkraut: 2 TBSP of frying oil - adjust if needed 1 large onion - peeled and finely chopped ½ LB of bacon - chopped into small pieces * 1 LB of Sauerkraut (drained, amount before draining) ½ Stick (2 OZ) of butter ½ TSP of salt ½ TSP of ground pepper * Skip for a vegetarian option Tools: Chef's Knife & Cutting Board Measuring Spoons & Measuring Cups Peeler Box Grater or Kitchen Mixer with Grater Attachment or Food Processor Immersion Blender or Food Processor or Blender 2 Large Mixing Bowls (about 8 QT or more) Silicone Spatula Large Sauce Pan or Medium Pot (about 6 QT) Large Fry Pan or Large Stir Fry Pan - Wok or Large Sauté Pan (12" or more) Halusky/Spaetzle Press or Colander (with Holes about ¼”) Strainer www.cookingwithfamily.com Cooking with Family © 2021 1 Directions: 1. Potato preparation: 1.1. Briefly rinse the potatoes under cold water and then peel. 1.2. Shred the potatoes into a large mixing bowl. Use the fine-sized holes for shredding. 2. Halušky batter: 2.1. Add: 1 large egg ½ TSP of salt Thoroughly stir together with a spatula until nicely combined. 2.2. Process until smooth with an immersion blender. 2.3. -

The Igbo Traditional Food System Documented in Four States in Southern Nigeria

Chapter 12 The Igbo traditional food system documented in four states in southern Nigeria . ELIZABETH C. OKEKE, PH.D.1 . HENRIETTA N. ENE-OBONG, PH.D.1 . ANTHONIA O. UZUEGBUNAM, PH.D.2 . ALFRED OZIOKO3,4. SIMON I. UMEH5 . NNAEMEKA CHUKWUONE6 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems 251 Study Area Igboland Area States Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State Ubulu-Uku/Alumu in Delta State Lagos Nigeria Figure 12.1 Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State Ede-Oballa/Ukehe IGBO TERRITORY in Enugu State Participating Communities Data from ESRI Global GIS, 2006. Walter Hitschfield Geographic Information Centre, McGill University Library. 1 Department of 3 Home Science, Bioresources Development 5 Nutrition and Dietetics, and Conservation Department of University of Nigeria, Program, UNN, Crop Science, UNN, Nsukka (UNN), Nigeria Nigeria Nigeria 4 6 2 International Centre Centre for Rural Social Science Unit, School for Ethnomedicine and Development and of General Studies, UNN, Drug Discovery, Cooperatives, UNN, Nigeria Nsukka, Nigeria Nigeria Photographic section >> XXXVI 252 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems | Igbo “Ndi mba ozo na-azu na-anwu n’aguu.” “People who depend on foreign food eventually die of hunger.” Igbo saying Abstract Introduction Traditional food systems play significant roles in maintaining the well-being and health of Indigenous Peoples. Yet, evidence Overall description of research area abounds showing that the traditional food base and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples are being eroded. This has resulted in the use of fewer species, decreased dietary diversity due wo communities were randomly to household food insecurity and consequently poor health sampled in each of four states: status. A documentation of the traditional food system of the Igbo culture area of Nigeria included food uses, nutritional Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State, value and contribution to nutrient intake, and was conducted Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State, in four randomly selected states in which the Igbo reside. -

How Batter Formulation Can Modify Fried Tempura-Battered Zucchini Chemical and Sensory Characteristics?

foods Article How Batter Formulation Can Modify Fried Tempura-Battered Zucchini Chemical and Sensory Characteristics? Montserrat Martínez-Pineda * , Cristina Yagüe-Ruiz and Antonio Vercet Faculty of Health and Sports Science, University of Zaragoza, Plaza Universidad, 3. 22002 Huesca, Spain; [email protected] (C.Y.-R.); [email protected] (A.V.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-974-292759 Received: 18 April 2020; Accepted: 7 May 2020; Published: 13 May 2020 Abstract: Tempura-fried vegetables are widely consumed and are greatly appreciated because of their characteristic dry and crispy crust, flavor and a golden–brown color. This study examined the effect of slice thickness, frying time and partial ingredient substitution in tempura batter with maltodextrin, ethanol, baking powder and cornflour on the rheological characteristics, moisture, oil uptake, color, texture and sensory characteristics of tempura-fried zucchini. The results showed an improved golden–brown coloring of the crust without affecting oil uptake when maltodextrin was included in the batter formulation. Moreover, dough viscosity and % pick-up lowered with maltodextrin addition. The partial substitution of water and wheat flour with ethanol, cornflour and baking powder resulted in a crispier and rougher crust that remained more stable over time but with less moisture and higher oil uptake. The substitution of certain tempura batter ingredients depending on the desired purpose could represent an interesting strategy to improve the quality of battered fried vegetables. Keywords: coating; ethanol; hydrocolloid; maltodextrin; oil; crispiness; tempura-batter; organoleptic characteristics 1. Introduction Despite variations in culinary traditions around the world [1] fried products are appreciated worldwide, in part due to their palatability. -

Breakfast Cereal: Porridge

Healthy Eating/ Gola/Mr. Conlon Student: ________________ Breakfast Cereal: Porridge “Morning, Did you know that Porridge is a great way to start the day? It’s full of vitamins, minerals, fibre and low in salt and sugar. My wife here makes really tasty porridge. Here’s her recipe. Enjoy!” Colour the Bears Benefits of Porridge Oats Clean the arteries in your body Help protect against cancer & heart disease Help lower cholesterol Help keep obesity at bay Reduce blood pressure and are a good source of vitamin B1 crucial for the nervous system Colour the Pictures OATS Healthy Eating/ Gola/Mr. Conlon Student: ________________ Mama Bear’s Recipes (4 types of porridge) MMMH Ingredients MMH MMH!! For basic porridge which serves 4 bears 200 g rolled oats 750 ml milk or water sea salt Place the oats and milk/water in a pan with a small pinch of sea salt Put on a medium heat Bring to a steady simmer for 5 to 6 minutes, stirring as often as you can to give a smooth creamy porridge Add the ingredients below for blackberry and apple porridge 1 apple 2-3 tablespoons runny honey, to taste 100 g blackberries for banana, almond and cinnamon porridge 2 ripe bananas 30 g flaked almonds ½ teaspoon ground cinnamon 2 tablespoons poppy seeds 2-3 tablespoons maple syrup or runny honey, to taste for apple, maple syrup and pecan porridge 1 apple 30 g pecans 2-3 tablespoons maple syrup, to taste Healthy Eating/ Gola/Mr. Conlon Student: ________________ Answer the questions on Mama Bear’s Recipes 1. -

Greens, Beans & Groundnuts African American Foodways

Greens, Beans & Groundnuts African American Foodways City of Bowie Museums Belair Mansion 12207 Tulip Grove Drive Bowie MD 20715 301-809-3089Email: [email protected]/museum Greens, Beans & Groundnuts -African American Foodways Belair Mansion City of Bowie Museums Background: From 1619 until 1807 (when the U.S. Constitution banned the further IMPORTATION of slaves), many Africans arrived on the shores of a new and strange country – the American colonies. They did not come to the colonies by their own choice. They were slaves, captured in their native land (Africa) and brought across the ocean to a very different place than what they knew at home. Often, slaves worked as cooks in the homes of their owners. The food they had prepared and eaten in Africa was different from food eaten by most colonists. But, many of the things that Africans were used to eating at home quickly became a part of what American colonists ate in their homes. Many of those foods are what we call “soul food,” and foods are still part of our diverse American culture today. Food From Africa: Most of the slaves who came to Maryland and Virginia came from the West Coast of Africa. Ghana, Gambia, Nigeria, Togo, Mali, Sierra Leone, Benin, Senegal, Guinea, the Ivory Coast are the countries of West Africa. Foods consumed in the Western part of Africa were (and still are) very starchy, like rice and yams. Rice grew well on the western coast of Africa because of frequent rain. Rice actually grows in water. Other important foods were cassava (a root vegetable similar to a potato), plantains (which look like bananas but are not as sweet) and a wide assortment of beans. -

Tydes – Nov 2019

www.lyondemere.org The Tydes Volume 41, Issue 2 A.S. LIV November 2019 A quarterly newsletter serving the Barony of Lyondemere, Kingdom of Caid . (Lyondemere comprises the coastal Los Angeles area of California). 41(2) A.S. LIV Nov 2019 The Tydes 1 www.lyondemere.org The Tydes Volume 41, Issue 2 A.S. LIV Nov 2019 Inside this issue: From the Baronage 3 Guide to Submissions August Council Minutes 4 Articles and Artwork (including photos) are due by the 25th September Council Minutes 5 of January, for the February publication. If you have difficulties with this deadline, please contact the Chronicler in advance, at October Council Minutes 7 [email protected] Announcement 9 Publish Dates: The Tydes is ambitiously published on the 1st of the month for the previous quarter (e.g., May 1 for Q4 of Feb- Ypocras and Spice 10 Mar-Apr). Baronial Progress 18 Articles: Please submit either an email, text, or Word file for all Email list, Groups, Regnum 19 articles and columns. Email is preferred, sent to [email protected] Artwork / Photos: Original drawings or photos are always appreciated. The Tydes Team Chronicler (Newsletter Editor): Lady Batu Sechen Tsagaajin, Lady Avicia de Na Baiona Proof-reading Staff: Dame Eilidh Swann, Lady Avicia de Na Baiona, Lord Geiri Smiđsson Copyright © 2019 Society for Creative Anachronism, Inc. All rights reserved. The Tydes is a quarterly publication of the Barony of Lyondemere of the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA), Inc. The Tydes is available from the Lyondemere Chronicler (see address below). It is not a corporate publication of the SCA, Inc. -

The Manufacture of Liquors and Preserves/' M

THE MANUFACTURE OF Liquors and Preserves. TRANSLATED FRpM THE FRENCH OF J. DC ]3 REVANS, Chief C iemist of the Municipal Laboratory of Paris. WITH SIXTY-FIVE ILLUSTRATIONS. Entered at Stationers' Hall. New York : MUNN & CO. 1893. Copyrighted, 1893, by Munn & Co. Macgowan & 8lipper, Printers, 30 Beekman Street, New York, N. Y., U. S. A. A clear and precise manual for the distiller and liquor manufacturer has long been needed in France—a book which by its scope, form and price would be within the reach of all, but never- theless would be complete enough to give a true picture of the recent discoveries and the true state of the art in this important branch of our na- tional industry. This want has been filled by " The Manufacture of Liquors and Preserves/' M. De Brevans, in writing the book, which we have the pleasure of presenting to the public, has accomplished a great service to manufacturers, chemists, etc. The first part comprises the study of liquors, that is to say, alcohol and natural liquors (brandy, rum, tafia). M. De Brevans says that there is rum which has never seen the Antilles and kirsch to which the cherry is a perfect stranger, both being spirituous mixtures made by mixing various chemicals and pharmaceutical products—an art which our neighbors beyond the Rhine have fully mastered. In the second part the author studies artificial liquors, some pages being devoted to a descrip- tion of the laboratory and plant of the distiller, including raw materials, alcohol, essences, spirits, tinctures, distilled waters, juices, sirups, etc., without forgetting the coloring matters. -

November 15, 2019 • Chicago

November 15, 2019 • Chicago Tele • 312-832-9800 | Fax • 312-832-9311 | [email protected] | www.susanins.com 900 South Clinton Street | Chicago, IL 60607, USA Fine Silver Auction 228 Online Only! Friday * November 15th, 2019 10:00 AM REGULAR BUSINESS HOURS Monday - Friday • 10:00 am - 4:00 pm Auction Day • 9:00 am - End of Auction Saturdays & Sundays • Closed AUCTION VIEWING HOURS Monday, November 11th * 10 am - 4 pm Tuesday, November 12th * 10 am - 4 pm Wednesday, November 13th * 10 am - 4 pm Thursday, November 14th * 10 am - 4 pm Friday, November 15th * Online Only! PROPERTY PICK UP Friday, November 15th - Friday, November 22nd 10:00 am - 4:00 pm Strict pick up policy in force — All property not paid for within 3 business days following the auction will be charged to the card on file. Any property not picked up within 7 business days will be stored at the expense of the buyer. Thank you for your understanding and cooperation. Tele • 312-832-9800 | Fax • 312-832-9311 | [email protected] | www.susanins.com 900 South Clinton Street | Chicago, IL 60607, USA DIRECTORY Illinois Auction License #440-000833 PHONE•312-832-9800 | FAX•312-832-9311 | EMAIL•[email protected] BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT TRUSTS AND ESTATES Sean E. Susanin, ISA — 312-832-9800— [email protected] CONSIGNOR SERVICES Patrick Kearney, ISA — 312-832-9037 — [email protected] Carrie Young, ISA — 312-832-9036 — [email protected] DIGITAL MEDIA PRODUCTION J’evon Covington — 312-832-9800 — [email protected] Assistant - Carey Primeau BIDDER SERVICES Christine Skarulis –– 312-832-9800 –– [email protected] Elizabeth Jensen — 312-832-9800 — [email protected] EXHIBITIONS Alex Adler –– 312-832-9034 –– [email protected] Assistant - Carey Primeau BUILDING MANAGEMENT Santiago Rosales AUCTIONEERS Sean Susanin, Marilee Judd INQUIRE ABOUT RESERVING SUSANIN’S FACILITY FOR LUNCHEONS, LECTURES, MEETINGS AND EVENTS. -

Know Your · a S

MAGR Extension Folder 177 GOVS Revised October 1957 MN 2000 EF-no.177 (Rev.1957:0ct.) Know Your · A s by ELEANOR LOOMIS .,~I UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Agricultural Extension Service U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Know Your Minnesota Apples Variety Season of use Characteristics Use Oriole August Large summer apple, orange-yellow, striped with Dessert, pie, sauce, freezing red. Very good eating and cooking quality. Duchess August-September Early, cooking apple. Medium size, striped with Pie, sauce, jelly, freezing red. Too tart for good eating. Beacon August-September Medium size, very attractive red. Mild subacid. Dessert, pie, sauce, freezing Better for eating than Duchess; keeps longer. Wealthy September-November Long a favorite in Minnesota for eating and cook Dessert, baking, pie, sauce, ing. Medium size, striped red. jelly, freezing Lakeland September-December Medium size, solid red color, pleasant flavor. Slices Dessert, pie, baking, sauce, hold shape when cooked. freezing Minjon September-December Below medium size, very attractive red. Flesh Dessert, pie, baking, sauce, somewhat tart, stained with red. freezing McIntosh October-January Medium size, nearly solid bright red. High quality Dessert, pie, sauce, jelly, for eating. Rich flavor, but soft when cooked. freezing Cortland October-January Medium size, attractive red; white flesh similar Dessert, pie, baking, sauce, to McIntosh. Holds fresh color well in salad. jelly, salad, freezing Redwell October-January Large size, attractive red. Pleasant flavor, subacid. Dessert, baking, sauce Jonathan October-February Below medium size, solid bright red. A favorite Dessert, pie, baking, sauce, variety for all uses. jelly, canning, freezing Haralson October-March Medium size, attractive red.