Downloaded From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Intellectual Role of Ulama in Modern Indonesia

ARTIKEL E-ISSN: 2615-5028 Harmonizing the Community: An Intellectual Role of Ulama in Modern Indonesia Moeflich Hasbullah (UIN Sunan Gunung Djati, Bandung; [email protected]) Abstrak Artikel ini menganalisis peran intelektual ulama sebagai perantara budaya dalam masyarakat dari beberapa tahap dalam sejarah Indonesia. Bab-bab terpenting dalam sejarah Indonesia secara umum dapat dibagi menjadi lima periode: Pertama, periode masuknya Islam dan perkembangan awal islamisasi. Kedua, masa penjajahan. Ketiga, era era modern, yaitu munculnya gerakan modern dalam Islam di awal abad ke-20. Keempat, periode kemerdekaan revolusioner, dan kelima, periode pasca-kemerdekaan. Artikel sosio-historis ini melihat bahwa ulama di setiap periode ini adalah aktor utama sejarah dan menentukan arah perkembangan bangsa Indonesia. Khusus untuk bagian 'pembangunan komunitas' dalam penelitian ini, kasus peran seorang ulama yang merupakan kepala desa di Rancapanggung, Cililin, Bandung Barat pada 1930-an. Kata kunci: Peran pemimpin, keharmonisan sosial, islamisasi Indonesia Abstract This article analyzes the ulama's intellectual role as a cultural broker in society from several stages in Indonesian history. The most important chapters in Indonesian history can generally be divided into five periods: First, the period of the entry of Islam and the early development of Islamization. Second, the colonial period. Third, the era of modern era, namely the emergence of modern movements in Islam in the early 20th century. Fourth, the revolutionary period of independence, and fifth, the post-independence period. This socio-historical article sees that the ulama in each of these periods is the main actor of history and determines the direction of the development of the Indonesian nation. -

Bab Iii Biografi Teuku Umar

BAB III BIOGRAFI TEUKU UMAR A. Kelahiran dan Masa Muda Teuku Umar Teuku Umar Johan Pahlawan lahir pada tahun 1854 M di Meulaboh, tepatnya di Gampong Masjid, sekarang Gampong Belakang, Kecamatan Johan Pahlawan. Ia dilahirkan dari seorang ayah yang bernama Teuku Tjut Mahmud dan ibu Tjut Mohani di mana pasangan ini dikarunia empat anak yaitu Teuku Musa, Tjut Intan, Teuku Umar dan Teuku Mansur.75 Teuku Umar seorang Aceh dan memiliki silsilah dengan Teuku Laksamana Muda Nanta, seorang Laksamana Aceh yang ditugaskan oleh Sultan Iskandar Muda pada tahun 1635 M sebagai Panglima Angkatan Perang Aceh di Andalas Barat dan sekaligus ditunjuk menjadi Gubernur Militer Aceh di Tanah Minang.76 Ayahnya, Teuku Achmad Mahmud, adalah seorang uleebalang (kepala daerah). Sementara ibundanya berasal dari lingkungan istana kerajaan di Meulaboh. Dalam buku Ensiklopedi Pahlawan Nasional yang disusun Julinar Said dan kawan-kawan (1995) disebutkan, dari garis ayahnya, Teuku Umar berdarah Minangkabau.77 Antara keluarga Teuku Umar dengan tanah rencong memang terikat terjalin kedekatan sejak dulu. Umar keturunan Datuk Makhudum Sati orang kepercayaan Sultan Iskandar Muda (1607-1636 M), yang diberi wewenang untuk memimpin wilayah Pariaman di Sumatera Barat sebagai bagian dari Kesultanan Aceh kala itu.78 Pada Tahun 1800 M, anak keturunan Teuku Laksamana Muda Nanta mendapatkan tekanan dari kaum ulama di tanah Andalas sehingga menyebabkan 75Ria Listina, Biografi Pahlawan Kusuma Bangsa, ( Jakarta: PT. Sarana Bangun Pustaka, 2010), hlm.22 76Ibid, hlm. 24 77Ragil Suwarna Pragolapati, Cut Nya Dien, Volume 1, 1982, hlm. 14 78Ibid, hlm. 21 40 mereka kembali ke Aceh lewat jalur laut sebelah barat dan kemudian mereka mendarat di Meulaboh di mana salah satu pemimpin rombongan tersebut bernama Machdum Sakti Yang Bergelar Teuku Nanta Teulenbeh yang kemudian diangkat oleh Sultan Aceh sebagai penjaga Taman Sultan di Kutaraja.79 Teuku Umar yang membangkitkan semangat perlawanan terhadap Belanda. -

And Bugis) in the Riau Islands

ISSN 0219-3213 2018 no. 12 Trends in Southeast Asia LIVING ON THE EDGE: BEING MALAY (AND BUGIS) IN THE RIAU ISLANDS ANDREW M. CARRUTHERS TRS12/18s ISBN 978-981-4818-61-2 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 789814 818612 Trends in Southeast Asia 18-J04027 01 Trends_2018-12.indd 1 19/6/18 8:05 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre (NSC) and the Singapore APEC Study Centre. ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 18-J04027 01 Trends_2018-12.indd 2 19/6/18 8:05 AM 2018 no. 12 Trends in Southeast Asia LIVING ON THE EDGE: BEING MALAY (AND BUGIS) IN THE RIAU ISLANDS ANDREW M. CARRUTHERS 18-J04027 01 Trends_2018-12.indd 3 19/6/18 8:05 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2018 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

National Heroes in Indonesian History Text Book

Paramita:Paramita: Historical Historical Studies Studies Journal, Journal, 29(2) 29(2) 2019: 2019 119 -129 ISSN: 0854-0039, E-ISSN: 2407-5825 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15294/paramita.v29i2.16217 NATIONAL HEROES IN INDONESIAN HISTORY TEXT BOOK Suwito Eko Pramono, Tsabit Azinar Ahmad, Putri Agus Wijayati Department of History, Faculty of Social Sciences, Universitas Negeri Semarang ABSTRACT ABSTRAK History education has an essential role in Pendidikan sejarah memiliki peran penting building the character of society. One of the dalam membangun karakter masyarakat. Sa- advantages of learning history in terms of val- lah satu keuntungan dari belajar sejarah dalam ue inculcation is the existence of a hero who is hal penanaman nilai adalah keberadaan pahla- made a role model. Historical figures become wan yang dijadikan panutan. Tokoh sejarah best practices in the internalization of values. menjadi praktik terbaik dalam internalisasi However, the study of heroism and efforts to nilai. Namun, studi tentang kepahlawanan instill it in history learning has not been done dan upaya menanamkannya dalam pembelaja- much. Therefore, researchers are interested in ran sejarah belum banyak dilakukan. Oleh reviewing the values of bravery and internali- karena itu, peneliti tertarik untuk meninjau zation in education. Through textbook studies nilai-nilai keberanian dan internalisasi dalam and curriculum analysis, researchers can col- pendidikan. Melalui studi buku teks dan ana- lect data about national heroes in the context lisis kurikulum, peneliti dapat mengumpulkan of learning. The results showed that not all data tentang pahlawan nasional dalam national heroes were included in textbooks. konteks pembelajaran. Hasil penelitian Besides, not all the heroes mentioned in the menunjukkan bahwa tidak semua pahlawan book are specifically reviewed. -

Analysis of M. Natsir's Thoughts on Islamic

Integral-Universal Education: Analysis of M. Natsir’s Thoughts on Islamic Education Kasmuri Selamat Universitas Islam Negeri (UIN) Sultan Syarif Kasim, Riau, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract. This paper aimed at exploring M. Natsir's thoughts on Islamic education. Using a qualitative study with a historical approach, the writer found that M. Natsir was a rare figure. He was not only a scholar but also a thinker, a politician, and an educator. As an educator, he not only became a teacher, but also gave birth to various educational concepts known as an integral and universal education concept. He was an architect and an anti-dichotomous thinker of Islamic education. According to Natsir, Islam did not separate spiritual matters from worldly affairs. The spiritual aspect would be the basis of worldliness. The foregoing indicated that religious ethics emphasized by Islamic teachings must be the foundation of life. The conceptual basis of "educational modernism" with tauhid as its foundation demonstrated that he was a figure who really cared about Islamic education. Keywords: Integral-Universal Education, M. Natsir, Thought Introduction Minangkabau, West Sumatra, is one of the areas that cannot be underestimated because there are many great figures on the national and international scales in various fields of expertise from this area, such as scholars, politicians, and other strategic fields. Among these figures are Tuanku Imam Bonjol, Haji Agus Salim, Sutan Sjahrir, Hamka, M. Natsir, and others. Everybody knows these names and their works. These figures lived in the early 20th century when three ideological groups competed with one another to dominate in the struggle for independence. -

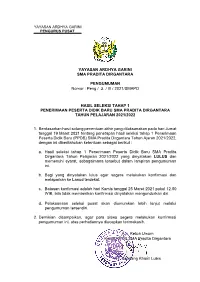

Pengumuman-Tahap-1-Ppdb

YAYASAN ARDHYA GARINI PENGURUS PUSAT YAYASAN ARDHYA GARINI SMA PRADITA DIRGANTARA PENGUMUMAN Nomor : Peng / 2 / III / 2021/SMAPD HASIL SELEKSI TAHAP 1 PENERIMAAN PESERTA DIDIK BARU SMA PRADITA DIRGANTARA TAHUN PELAJARAN 2021/2022 1. Berdasarkan hasil sidang penentuan akhir yang dilaksanakan pada hari Jumat tanggal 19 Maret 2021 tentang penetapan hasil seleksi tahap 1 Penerimaan Peserta Didik Baru (PPDB) SMA Pradita Dirgantara Tahun Ajaran 2021/2022, dengan ini diberitahukan ketentuan sebagai berikut : a. Hasil seleksi tahap 1 Penerimaan Peserta Didik Baru SMA Pradita Dirgantara Tahun Pelajaran 2021/2022 yang dinyatakan LULUS dan memenuhi syarat, sebagaimana tersebut dalam lampiran pengumuman ini. b. Bagi yang dinyatakan lulus agar segera melakukan konfirmasi dan melaporkan ke Lanud terdekat. c. Batasan konfirmasi adalah hari Kamis tanggal 25 Maret 2021 pukul 12.00 WIB, bila tidak memberikan konfirmasi dinyatakan mengundurkan diri. d. Pelaksanaan seleksi pusat akan diumumkan lebih lanjut melalui pengumuman tersendiri. 2. Demikian disampaikan, agar para siswa segera melakukan konfirmasi pengumuman ini, atas perhatiannya diucapkan terimakasih. A.n. Ketua Umum Ketua PPDB SMA Pradita Dirgantara Ny. Sondang Khairil Lubis Lampiran Pengumuman Daftar Nama Peserta Lolos Seleksi Tahap 1 NO KODE DAFTAR NAMA JK ASAL PANDA 1 2 3 4 5 1 PRAK-83JQEKIC Az Zahra Leilany Widjanarka P Lanud Abdul Rachman Saleh (ABD), Malang 2 PRAK-8TM1YQGC Glenn Emmanuel Abraham L Lanud Abdul Rachman Saleh (ABD), Malang 3 PRAK-202101-0879 Kayana Nur Ramadhania P Lanud Abdul -

The Impact of Forest and Peatland Exploitation Towards Decreasing Biodiversity of Fishes in Rangau River, Riau-Indonesia

I J A B E R, Vol. 14, No. 14 (2016): 10343-10355 THE IMPACT OF FOREST AND PEATLAND EXPLOITATION TOWARDS DECREASING BIODIVERSITY OF FISHES IN RANGAU RIVER, RIAU-INDONESIA Yustina* Abstract: This survey study was periodically conducted in July, 6 times every year. There were 3 periods: 1st period (2002); 2nd period (2008) and 3rd period (2014). It sheds light on the impact of forest and peat land exploitation on decreasing biodiversity of fishes in Rangau River, Riau- Indonesia. Using some catching tools such as landing net, fishing trap, fishnet stocking and fishing rod. The sampling activity was administered at eight stations which were conducted by applying “catch per unit effort technique” in primary time: 19.30-07.30, for 3 repetitions for each fish net measurement within 30 minutes at every station, at position or continuously casting. The sampled fish were selected which were relatively in minor size but had represent their features and species. The fish were labelled and were preserved with 40% formalin. The determination and identification of fish were conducted at laboratory. Secondary data was collected by mean of interviewing the local fishermen about the surrounding environment condition of Rangau river. Data analysis consisted of biodiversity data, biodiversity index and fish existence frequency. The finding in 1st period, in 2002, total caught fish were 60 species: 36 genera and 17 families. In 2nd period in 2008, total caught fish were 38 species which consist of 30 genera and 16 families. In 3rd period, in 2014, there were 23 of fish species were found comprising 17 genera, 12 families. -

Peraturan Badan Informasi Geospasial

PERATURAN BADAN INFORMASI GEOSPASIAL REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR 16 TAHUN 2019 TENTANG SATUAN HARGA PENYELENGGARAAN INFORMASI GEOSPASIAL TAHUN ANGGARAN 2020 PADA BADAN INFORMASI GEOSPASIAL KEPALA BADAN INFORMASI GEOSPASIAL REPUBLIK INDONESIA, Menimbang : a. bahwa untuk mendukung penyelenggaraan informasi geospasial melalui mekanisme pengadaan barang/jasa pemerintah, diperlukan satuan harga lain selain standar biaya masukan sebagaimana telah ditetapkan dengan Peraturan Menteri Keuangan; b. bahwa berdasarkan ketentuan Pasal 8 ayat (2) huruf b Peraturan Menteri Keuangan Nomor 71/PMK.02/2013 tentang Pedoman Standar Biaya, Standar Struktur Biaya, dan Indeksasi Dalam Penyusunan Rencana Kerja dan Anggaran Kementerian Negara/Lembaga sebagaimana telah diubah dengan Peraturan Menteri Keuangan Nomor 51/PMK.02/2014 tentang Perubahan Atas Peraturan Menteri Keuangan Nomor 71/PMK.02/2013 tentang Pedoman Standar Biaya, Standar Struktur Biaya, dan Indeksasi Dalam Penyusunan Rencana Kerja dan Anggaran Kementerian Negara/Lembaga, Kepala Badan Informasi Geospasial diberikan kewenangan untuk menetapkan satuan harga; - 2 - c. bahwa berdasarkan pertimbangan sebagaimana dimaksud dalam huruf a, dan huruf b, perlu menetapkan Peraturan Badan Informasi Geospasial tentang Satuan Harga Penyelenggaraan Informasi Geospasial Tahun Anggaran 2020 pada Badan Informasi Geospasial; Mengingat : 1. Peraturan Presiden Nomor 16 Tahun 2018 tentang Pengadaan Barang/Jasa Pemerintah (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2018 Nomor 33); 2. Peraturan Presiden Nomor 94 Tahun 2011 tentang -

Analysis of the Appropriateness of Actual Land Use to Land Use in Spatial Planning in the Catchment Area of the Koto Panjang Hydro Power Plant Reservoir

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2015): 78.96 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Analysis of the Appropriateness of Actual Land Use to Land Use in Spatial Planning in the Catchment Area of the Koto Panjang Hydro Power Plant Reservoir The part of Dissertation Nurdin1, S. Bahri2 1Student Doctor of Environmental Science UR, Pekanbaru 2Department of Chemical Engineering Faculty of Engineering UR, Pekanbru Abstract: The Koto Panjang Hydro Power Plant Reservoir is located in three districts namely Kampar Regency of Riau Province, Pasaman Regency and Lima Puluh Kota of West Sumatera Province, so that the direction of actual land use is based on the spatial plan of three districts . The purpose of this study is to find out the land cover index by vegetation and the appropriateness between actual land use with spatial plan in the catchment area of Koto Pajang Hydro Power Plant Reservoir. The research was conducted by the method of interpretation of Landsat 8 image of 2014 recording which then overlaid on the combined spatial plant of Kampar, Pasaman and Lima Puluh Kota Regency in the catchment area of Koto Panjang Hydro Power Plan Reservoir processed using Geographic Infomation System technology. The result of Landsat 8 image interpretation in 2014 based on land use class in catchment area of Koto Panjang Hydro Power Plant Reservoir, to obtain land cover index value (IPL) by vegetation 97,16% greater 75%, meaning that the cover condition is in good condition. Spatial Plan of Kabupaten Kampar, Pasaman and Lima Puluh Kota in the catchment area Koto Panjang Hydro Power Plant Reservoir has wide use of forest land 209.587,36 ha or 65,86% from land area of Spatial Plant has forest forest area 140.392.22 ha or 44,12% from Land area of catchment area. -

Manajemen Konflik Di Tengah Dinamika Pondok Pesantren Dan Madrasah

Bashori / Manajemen Konflik Di Tengah Dinamika ... 353 MANAJEMEN KONFLIK DI TENGAH DINAMIKA PONDOK PESANTREN DAN MADRASAH Bashori STAI Tuanku Tambusai Pasir Pengaraian email: [email protected] Abstract In the dynamics of Islamic education institutions, certainly there will be any turmoil or conflict, either conflict between individual or conflict between groups. Recognized or not, the Islamic educational institutions, particularly pondok pesantren and madrasah, have the possibility of conflict is quite high compared with other educational institutions. From that assumption, this article aims to analyze the role of conflict management in resolving conflicts in the scope of Islamic educational institutions. Based on the study of theory, it can be concluded that the conflict management to be very central in developing the conflicts that exist in educational institutions Islamic school as a way to develop Islamic educational institutions for the better. In addition, because it has become a necessity that the conflict can not be avoided, then controlling the conflict becomes imperative in order to achieve objectives in Islamic educational institutions. Abstrak Dalam dinamika lembaga pendidikan Islam, pasti munsul gejolak atau konflik, baik konflik secara individu maupun konflik secara kelompok. Diakui atau tidak, lembaga pendidikan Islam khususnya pondok pesantren dan madrasah, memiliki kemungkinan konflik yang cukup tinggi dibandingkan dengan lembaga pendidikan yang lain. Dari asumsi itulah tulisan ini bertujuan menganalisis peranan manajemen konflik dalam menyelesaikan konflik yang terjadi di lingkup lembaga pendidikan Islam. Berdasarkan kajian teori, dapat disimpulkan bahwa manajemen konflik menjadi sangat sentral dalam mengembangkan konflik yang ada di lembaga pendidikan pondok pesantren dan madrasah sebagai cara dalam mengembangkan lembaga pendidikan Islam menjadi lebih baik. -

Dermaga-Sastra-Indon

Dermaga Sastra Indonesia Kepengarangan Tanjungpinang dari Raja Ali Haji sampai Suryatati A. Manan komodo books komodo books DERMAGA SASTRA INDONESIA: Kepengarangan Tanjungpinang dari Raja Ali Haji sampai Suryatati A Manan Tim Penyusun: Pelindung: Dra. Hj. Suryatati A. Manan (Walikota Tanjungpinang) Drs. Edward Mushalli (Wakil Walikota Tanjungpinang) Penasehat: Drs. Gatot Winoto, M.T. (Plt. Sekretaris Daerah Kota Tanjungpinang) Penanggung Jawab: Drs. Abdul Kadir Ibrahim, M.T. (Kepala Dinas Kebudayaan dan Pariwisata Kota Tanjungpinang) Ketua: Drs. Jamal D. Rahman, M. Hum. Wakil Ketua: Syafaruddin, S.Sn., M.M. Sekretaris: Said Hamid, S.Sos. Anggota: Drs. Al azhar Drs. H. Abdul Malik, M.Pd. Drs. Agus R. Sarjono, M. Hum. Raja Malik Afrizal Desain dan Visualisi Isi: Drs. Tugas Suprianto Pemeriksa Aksara: Muhammad Al Faris ISBN: 979-98965-6-3-2 Diterbitkan oleh Dinas Kebudayaan dan Pariwisata Kota Tanjungpinang, Kepulauan Riau bekerja sama dengan Penerbit Komodo Books, Jakarta ii DERMAGA SASTRA INDONESIA WALIKOTA TANJUNGPINANG SAMBUTAN WALIKOTA TANJUNGPINANG Bismillâhirrahmânirrahîm. Assalâmu‘alaikum warahmatullâhi wabarakâtuh. Salam sejahtera bagi kita semua. Encik-encik, Tuan-tuan, Puan-puan, dan para pembaca yang saya hormati, Pertama-tama marilah kita mengucapkan puji syukur kepada Allah SWT., Tuhan Yang Maha Esa, karena atas limpahan rahmat dan karunia-Nya jualah sehingga kita dapat melanjutkan aktivitas dan kreativitas masing-masing dalam rangka mencapai ridha-Nya. Shalawat dan salam senantiasa diucapkan untuk junjungan alam, Nabi Besar Muhammad SAW. Allâhumma shalli ‘alâ saiyidinâ Muhammad. Sidang pembaca yang saya muliakan, Terkait dan terbabit pertumbuhkembangan sastra Indo- nesia modern sampai dewasa ini, sejatinyalah tidak dapat dipisahkan dengan adanya sastra Melayu yang sentralnya antara lain di Pulau Penyengat, Kota Tanjungpinang, sejak berbilang abad yang lampau. -

The Genealogy of Muslim Radicalism in Indonesia A

The Genealogy of Muslim Radicalism in Indonesia THE GENEALOGY OF MUSLIM RADICALISM IN INDONESIA A Study of the Roots and Characteristics of the Padri Movement Abd A’la IAIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya, Indonesia Abstract: This paper will trace the roots of religious radicalism in Indonesia with the Padri movement as the case in point. It argues that the history of the Padri movement is complex and multifaceted. Nevertheless, it seems to be clear that the Padri movement was in many ways a reincarnation of its counterpart in the Arabian Peninsula, the Wahhabi> > movement, even though it was not a perfect replica of the latter. While the two shared some similarities, they were also quite different in other respects. The historical passage of the Padris was therefore not the same as that of the Wahhabi> s.> Each movement had its own dimensions and peculiarities according to its particular context and setting. Despite these differences, both were united by the same objective; they were radical in their determination to establish what they considered the purest version of Islam, and both manipulated religious symbols in pursuit of their political agendas. Keywords: Padri movement, fundamentalism, radicalism, Minangkabau, Wahhabism.> Introduction Almost all historians agree that Islam in the Malay Archipelago – a large part of which subsequently became known as Indonesia – was disseminated in a peaceful process. The people of the archipelago accepted the religion of Islam wholeheartedly without any pressure or compulsion. To a certain extent, these people even treated Islam as belonging to their own culture, seeing striking similarities between the new religion and existing local traditions.