Edexcel a Level Aos3: Music for Film, Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

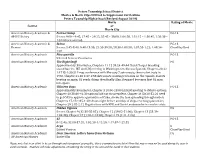

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

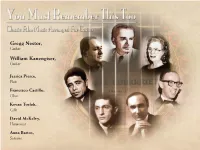

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

Softball Bat List, July 17, 2021

` Manufacturer Model Description Updated Adidas FPVQSH2K10 Vanquish 3/21/11 Adidas FPVQSH2K9 Vanquish 8/13/08 Adidas Phenom by Dick's Sporting Goods 8/13/08 Adidas Vanquish-FPVQSH2K8 by Dick's Sporting Goods 8/13/08 Akadema Catapult Black 9/16/09 Akadema Xtension 8/13/08 Akadema Xtension Catapult 8/13/08 Akadema Xtension Catapult Hybrid 8/13/08 Albin Athletics ACL-XO7FP 8/13/08 Albin Athletics ACL-XO7SP 8/13/08 Albin Athletics ASP07 8/13/08 Anarchy Bats A202ABDM2-2 Blue Dream 9/14/20 Anarchy Bats A20AASM1-1 Autism 11/5/20 Anarchy Bats A20AATS2-1 All The Smoke 11/5/20 Anarchy Bats A20ADAY2-1 22 A Day 11/5/20 Anarchy Bats A20ADMN2-1 Demon 11/5/20 Anarchy Bats A20AMUW2-1 Maui-Wowie 11/5/20 Anarchy Bats A20APPX2 Pineapple X 9/14/20 Anarchy Bats A20AREB2-2 Rebellion 11/5/20 Anarchy Bats A20AREB2-2 Rebellion 4/26/21 Anarchy Bats A20ASDL2-1 Sour Diesel 11/5/20 Anarchy Bats A20AUND1-1 Unite 9/14/20 Anarchy Bats A20AWC1A1 Awakening CE 6/22/20 Anarchy Bats A20BUD1A2 Budweiser (1oz) 6/22/20 Anarchy Bats A20BUD2A2 Budweiser (.5oz) 6/22/20 Anarchy Bats A20BUDL1A2 Bud Light (1oz) 6/22/20 Anarchy Bats A20BUDL2A2 Bud Light (.5oz) 6/22/20 Anarchy Bats A21ABHL12-1 Busch 6/22/21 Anarchy Bats A21ABLL13-1 Bud Lime 6/22/21 Anarchy Bats A21ADMSC13-2 Demon Supercharged 6/22/21 Anarchy Bats A21ADSC121-1 Diablo Super Charged 6/22/21 Anarchy Bats A21ADSCP13-2 Disciple 6/22/21 Anarchy Bats A21AIRCN12-1 Insurrection 6/22/21 Anarchy Bats A21AMUA13-2 Michelob 6/22/21 Anarchy Bats A21ANTD12-2 Naturday 6/22/21 Anarchy Bats A21AOKT13-2 Outkast 6/22/21 Anarchy Bats A21APRO12-1 -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

Musikliste Zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel Sortiert in Der Reihenfolge, in Der Sie in Der Doku Zu Hören Sind

Z Musikliste zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel sortiert in der Reihenfolge, in der sie in der Doku zu hören sind. Folge 1 MUSIK - Titel CD / Interpret Composer Trailer Terra X Trailer Terra X Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Dr. Ford Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Ramin Djawadi Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Eleven Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Race To Mark's Flat Bridget Jones's Baby / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Boggis, Bunce and Fantastic Mr. Fox / Alexandre Desplat Alexandre Desplat Bean Hibernation Pod 1625 Passengers / Thomas Newman Thomas Newman Jack It Up Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Letters Theodore Shapiro Reporters Swarm Confirmation / Harry Gregson Williams Harry Gregson Williams Persistence Burnt / Rob Simonsen Rob Simonsen Introducing Howard Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Inlet Theodore Shapiro The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Theodore Shapiro Letters Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Fell Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers Me Before You Me Before You / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Orchestral This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon The Skylab Plan Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Speight Lived Here The Knick (Season 2) / Cliff Martinez Cliff Martinez This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon 3 Minutes Of Moderat A New Beginning Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers 3 Minutes Of Moderat The Walk The Walk / Alan Silvestri Alan Silvestri Dr. -

Brazilian/American Trio São Paulo Underground Expands Psycho-Tropicalia Into New Dimensions on Cantos Invisíveis, a Global Tapestry That Transcends Place & Time

Bio information: SÃO PAULO UNDERGROUND Title: CANTOS INVISÍVEIS (Cuneiform Rune 423) Format: CD / DIGITAL Cuneiform Promotion Dept: (301) 589-8894 / Fax (301) 589-1819 Press and world radio: [email protected] | North American and world radio: [email protected] www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / TROPICALIA / ELECTRONIC / WORLD / PSYCHEDELIC / POST-JAZZ RELEASE DATE: OCTOBER 14, 2016 Brazilian/American Trio São Paulo Underground Expands Psycho-Tropicalia into New Dimensions on Cantos Invisíveis, a Global Tapestry that Transcends Place & Time Cantos Invisíveis is a wondrous album, a startling slab of 21st century trans-global music that mesmerizes, exhilarates and transports the listener to surreal dreamlands astride the equator. Never before has the fearless post-jazz, trans-continental trio São Paulo Underground sounded more confident than here on their fifth album and third release for Cuneiform. Weaving together a borderless electro-acoustic tapestry of North and South American, African and Asian, traditional folk and modern jazz, rock and electronica, the trio create music at once intimate and universal. On Cantos Invisíveis, nine tracks celebrate humanity by evoking lost haunts, enduring love, and the sheer delirious joy of making music together. São Paulo Underground fully manifests its expansive vision of a universal global music, one that blurs edges, transcends genres, defies national and temporal borders, and embraces humankind in its myriad physical and spiritual dimensions. Featuring three multi-instrumentalists, São Paulo Underground is the creation of Chicago-reared polymath Rob Mazurek (cornet, Mellotron, modular synthesizer, Moog Paraphonic, OP-1, percussion and voice) and two Brazilian masters of modern psycho- Tropicalia -- Mauricio Takara (drums, cavaquinho, electronics, Moog Werkstatt, percussion and voice) and Guilherme Granado (keyboards, synthesizers, sampler, percussion and voice). -

Arkansas Symphony Presents Music of Star Wars with Costumes, Trivia, and Music Attendees Are Invited to Attend in Costume for a Chance to Win a Prize

PRESS RELEASE: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Brandon Dorris Office: (501)666-1761, ext. 118 Mobile: (501)650-2260 Fax: (501)666-3193 Email: [email protected] Arkansas Symphony Presents Music of Star Wars with Costumes, Trivia, and Music Attendees are invited to attend in costume for a chance to win a prize. Little Rock, ARK, September 27, 2018 - The Arkansas Symphony Orchestra, Philip Mann, Music Director and Conductor, announces a presentation of The Music of Star Wars, 7:30 p.m. Saturday, October 20th and 3:00 p.m. Sunday, October 21st at the Robinson Center. The concert will feature music selected from the entire series of 10 feature films, an animated film, three TV films, and six animated series spanning more than 40 years. The celebrated film composer John Williams (Star Wars, Jaws, Indiana Jones, Harry Potter), composed all music from the eight saga films (Williams is also slated to score the ninth and final film), with award-winners Michael Giacchino and John Powell composing the music for the spin-off films. The program will feature costumes, trivia, and decoration of the Robinson Center to create a multi- sensory experience. Audiences are invited attend this family-friendly event in costume as their favorite character. A random Star Wars-themed prize winner will be selected from costumed attendees at each performance. Tickets are on sale now and prices are $16, $36, $57, and $68 and can be purchased online at www.ArkansasSymphony.org/starwars; at the Robinson Center street-level box office beginning 90 minutes prior to a concert; or by phone at 501-666-1761, ext. -

An October Film List for Cooler Evenings and Candlelit Rooms

AUTUMN An October Film List For cooler evenings and candlelit rooms. For tricks and treats and witches with brooms. For magic and mischief and fall feelings too. And good ghosts and bad ghosts who scare with a “boo!” For dark haunted houses and shadows about. And things unexplained that might make you shout. For autumn bliss with colorful trees or creepier classics... you’ll want to watch these. FESTIVE HALLOWEEN ANIMATED FAVORITES GOOD AUTUMN FEELS BEETLEJUICE CORALINE AUTUMN IN NEW YORK CASPER CORPSE BRIDE BAREFOOT IN THE PARK CLUE FANTASTIC MR. FOX BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S DARK SHADOWS FRANKENWEENIE DEAD POET’S SOCIETY DOUBLE DOUBLE TOIL AND TROUBLE HOTEL TRANSYLVANIA MOVIES GOOD WILL HUNTING E.T. JAMES AND THE GIANT PEACH ONE FINE DAY EDWARD SCISSORHANDS MONSTER HOUSE PRACTICAL MAGIC GHOSTBUSTERS PARANORMAN THE CRAFT HALLOWEENTOWN THE GREAT PUMPKIN CHARLIE BROWN THE WITCHES OF EASTWICK HOCUS POCUS THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS WHEN HARRY MET SALLY LABYRINTH YOU’VE GOT MAIL SLEEPY HOLLOW THE ADAMS FAMILY MOVIES THE HAUNTED MANSION THE WITCHES SCARY MOVIES A HAUNTING IN CONNECTICUT RELIC THE LODGE A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET ROSEMARY’S BABY THE MOTHMAN PROPHECIES AMMITYVILLE HORROR THE AUTOPSY OF JANE DOE THE NUN ANNABELLE MOVIES THE BABADOOK THE OTHERS AS ABOVE SO BELOW THE BIRDS THE POSSESSION CARRIE THE BLACKCOAT’S DAUGHTER THE POSSESSION OF HANNAH GRACE HALLOWEEN MOVIES THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT THE SHINING HOUSE ON HAUNTED HILL THE CONJURING MOVIES THE SIXTH SENSE INSIDIOUS MOVIES THE EXORCISM OF EMILY ROSE THE VILLAGE IT THE EXORCIST THE VISIT LIGHTS OUT THE GRUDGE THE WITCH MAMA THE HAUNTING THE WOMAN IN BLACK POLTERGEIST THE LAST EXORCISM It’s alljust a bit of hocus pocus.. -

Contemporary Film Music

Edited by LINDSAY COLEMAN & JOAKIM TILLMAN CONTEMPORARY FILM MUSIC INVESTIGATING CINEMA NARRATIVES AND COMPOSITION Contemporary Film Music Lindsay Coleman • Joakim Tillman Editors Contemporary Film Music Investigating Cinema Narratives and Composition Editors Lindsay Coleman Joakim Tillman Melbourne, Australia Stockholm, Sweden ISBN 978-1-137-57374-2 ISBN 978-1-137-57375-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57375-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931555 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

OA and EHP Models

University of St Augustine for Health Sciences SOAR @ USA San Marcos, Fall 2019 Research Day, San Marcos Campus 12-13-2019 Application of Occupation-Based Models to Edward of Edward Scissorhands: OA and EHP Models Amy Griswold University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, [email protected] Kelsey Harris University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences`, [email protected] Whitney Marwick University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, [email protected] Whitney Wilbanks University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, [email protected] Courtney Wild University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://soar.usa.edu/casmfall2019 Part of the Occupational Therapy Commons, and the Orthotics and Prosthetics Commons Recommended Citation Griswold, Amy; Harris, Kelsey; Marwick, Whitney; Wilbanks, Whitney; and Wild, Courtney, "Application of Occupation-Based Models to Edward of Edward Scissorhands: OA and EHP Models" (2019). San Marcos, Fall 2019. 12. https://soar.usa.edu/casmfall2019/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Day, San Marcos Campus at SOAR @ USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in San Marcos, Fall 2019 by an authorized administrator of SOAR @ USA. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Application of Occupation-Based Models to Edward of Edward Scissorhands: OA and EHP Models Amy Griswold OTDS, Kelsey Harris OTDS, Whitney Marwick MOTS, Whitney Wilbanks OTDS, Courtney Wild OTDS Abstract: This presentation examines the character Edward Scissorhands, a young adult with hand deformities and poor social skills, through the lens of the Ecological Human Performance Model. -

Halloween Concert

Music Department Calendar of Events Central Washington University Department of Music presents: Halloween Concert Dr. Elioac Salokin, Director of Orchestra Dr. Raanediew Yrag, Director of Choir Asomrehalliv Nayr, Assistant Conductor Renierhcs Leinad, Assistant Conductor Jerilyn S. McIntyre Music BuildingDr. Wayne S. Hertz Concert Hall Wednesday, October 30th, 2019 7:00 PM Personnel Program FARMING FOR TREBLE CANDY HORNS SNOWWHITE AND THE March of the Goblins Adam Glaser Cow Doctor* SEVEN DWARVES SoBEEa Goodenbuzz+ Jeffrey Snow White* Chicken Leighton Dopey Jerry Snedeker Doc Lydia BoPeep Sleepy Batalip+ THE POWERPUFF GIRLS Sneezy Old McDonald / Spider Pig arr. Mike Scott Tom Blossom* Grumpy Scarecrow Buttercup^ Bashful ed. Daniel Schreiner Bubbles Happy INNER VOICES, TRULY HEROIC SCRUFFY LOOKING NERF CELLO THERE Disgruntled Food Employee HERDERS Rey*^ Choir - Ecce Vicit Leo (Double) Peter Phillips Jack and Jill Payton Luke Skywalker* Palermo Charlotte Web Leia Organa Lucy Zoboomafoo Sheev Palpatine* Ricky Spooky Stuckey+ Han Solo* Pizza Ash Ketchum Poor College Student Savurkey Gobbler+ HYDROFLASKS Lilith Star Wars - Main Title John Williams Black Hydroflask* Princess Leia FARMERS ONLY Grey Hydroflask Greg Universe Erik Green Hydroflask The Rock Kornel Blue Hydroflask Something Wicked “High Ground”+ Red Hydroflask Renaissance Lady Gus Rrr’Donnell Mystery Man Eight Laughing Voices Hyo-won Woo Earl BLACK AND WHITE ALL Musical Superhero Old McDonald OVER Carina Kanter Farmer Mike BoJack Horseman Chip ROCK BOTTOM VIOLENT Mary Poppins* THE FLOCK SHOULDER HARPS Professor Utonium The Typewriter Leroy Anderson David Baa-allard Mrs. Elizabeth Peacock*^ One Ring to Rule Them All Elambjah Bergevin Andrés de Fonollosa Medical Officer Phipps Luke Baa-cheverria Captain Long John Silver Science Officer Hoffman Tommy Marsheep Mognarktharol, the Djent Electric Blue #7 Tyler Mathewes Zombie Arwen.