Luxury Brands and the Internet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brand Building

BRAND BUILDING inside the house of cÉline Breguet, theinnovator. Classique Hora Mundi 5717 An invitation to travel across the continents and oceans illustrated on three versions of the hand-guilloché lacquered dial, the Classique Hora Mundi is the first mechanical watch with an instant-jump time-zone display. Thanks to apatented mechanical memorybased on two heart-shaped cams, it instantlyindicates the date and the time of dayornight in agiven city selected using the dedicated pushpiece. Historyisstill being written... BREGUET BOUTIQUES –NEW YORK 646 692-6469 –BEVERLY HILLS 310860-9911 BAL HARBOUR 305 866-10 61 –LAS VEGAS 702733-7435 –TOLL FREE 877-891-1272 –WWW.BREGUET.COM Haute Joaillerie, place Vendôme since 1906 Audacious Butterflies Clip, pink gold, pink, mauve and purple sapphires, diamonds. Clip, white gold, black opals, malachite, lapis lazuli and diamonds. Visit our online boutique at vancleefarpels.com - 877-VAN-CLEEF The spirit of travel. Download the Louis Vuitton pass app to reveal exclusive content. 870 MADISON AVENUE NEW YORK H® AC CO 5 01 ©2 Coach Dreamers Chloë Grace Moretz/ Actress Coach Swagger 27 in patchwork floral Fluff Jacket in pink coach.com 800-457-TODS 800-457-TODS april 2015 16 EDITOR’S LETTER 20 CONTRIBUTORS 22 COLUMNISTS on Failure 116 STILL LIFE Mike Tyson The former heavyweight champion shares a few of his favorite things. Photography by Spencer Lowell What’s News. 25 The Whitney Museum of American Art Reopens With Largest Show Yet 28 Menswear Grooming Opts for Black Packaging The Texas Cocktail Scene Goes -

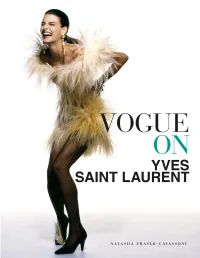

Vogue on Yves Saint Laurent

Model Carrie Nygren in Rive Gauche’s black double-breasted jacket and mid-calf skirt with long- sleeved white blouse; styled by Grace Coddington, photographed by Guy Bourdin, 1975. Linda Evangelista wears an ostrich-feathered couture slip dress inspired by Saint Laurent’s favourite dancer, Zizi Jeanmaire. Photograph by Patrick Demarchelier, 1987. At home in Marrakech, Yves Saint Laurent models his new ready-to-wear line, Rive Gauche Pour Homme. Photograph by Patrick Lichfield, 1969. DIOR’S DAUPHIN FASHION’S NEW GENIUS A STYLE REVOLUTION THE HOUSE THAT YVES AND PIERRE BUILT A GIANT OF COUTURE Index of Searchable Terms References Picture credits Acknowledgments “CHRISTIAN DIOR TAUGHT ME THE ESSENTIAL NOBILITY OF A COUTURIER’S CRAFT.” YVES SAINT LAURENT DIOR’S DAUPHIN n fashion history, Yves Saint Laurent remains the most influential I designer of the latter half of the twentieth century. Not only did he modernize women’s closets—most importantly introducing pants as essentials—but his extraordinary eye and technique allowed every shape and size to wear his clothes. “My job is to work for women,” he said. “Not only mannequins, beautiful women, or rich women. But all women.” True, he dressed the swans, as Truman Capote called the rarefied group of glamorous socialites such as Marella Agnelli and Nan Kempner, and the stars, such as Lauren Bacall and Catherine Deneuve, but he also gave tremendous happiness to his unknown clients across the world. Whatever the occasion, there was always a sense of being able to “count on Yves.” It was small wonder that British Vogue often called him “The Saint” because in his 40-year career women felt protected and almost blessed wearing his designs. -

PARIS Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

PARIS Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Cushman & Wakefield | Paris | 2019 0 Regarded as the fashion capital of the world, Paris is the retail, administrative and economic capital of France, accounting for near 20% of the French population and 30% of national GDP. Paris is one of the top global cities for tourists, offering many cultural pursuits for visitors. One of Paris’s main growth factors is new luxury hotel openings or re-openings and visitors from new developing countries, which are fuelling the luxury sector. This is shown by certain significant openings and department stores moving up-market. Other recent movements have accentuated the shift upmarket of areas in the Right Bank around Rue Saint-Honoré (40% of openings in 2018), rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, and Place Vendôme after the reopening of Louis Vuitton’s flagship in 2017. The Golden Triangle is back on the luxury market with some recent and upcoming openings on the Champs-Elysées and Avenue Montaigne. The accessible-luxury market segment is reaching maturity, and the largest French proponents have expanded abroad to find new growth markets. Other retailers such as Claudie Pierlot and The Kooples have grown opportunistically by consolidating their positions in Paris. Sustained demand from international retailers also reflects the current size of leading mass-market retailers including Primark, Uniqlo, Zara brands or H&M. In the food and beverage sector, a few high-end specialised retailers have enlivened markets in Paris, since Lafayette Gourmet has reopened on boulevard Haussmann, La Grande Épicerie in rue de Passy replacing Franck & Fils department store, and more recently the new concept Eataly in Le Marais. -

The LVMH Group Has Recently Issued a New Code of Conduct in Order to Address the Challenges in an Ever-Changing Environment Whil

The LVMH group has recently issued a new Code of Conduct in order to address the challenges in an ever-changing environment while upholding Ethics and Governance objectives. Bulgari is part of the LVMH group, shares its values and actively participates in building the foundations for its lasting success. Bulgari is a byword for excellence. Its authenticity, combined with the ability to evolve while also remaining true to its core values, are the qualities that determine its success. In the luxury goods market, brand leadership of this level is only possible thanks to the constant search for perfection: our creations are so highly coveted because they realize a dream and bring excitement into the lives of those who own them, thanks to their extraordinary quality. Today, as never before, leadership is strongly linked to credibility. Our clients and stakeholders fully rely on the fact that this dedication to excellence is reflected in extremely high standards of behavioral integrity and business practices at Bulgari. Compliance with the standards of the Responsible Jewellery Council is a concrete example of our commitment. Bulgari has decided to fully adopt the new LVMH Code of Conduct, whose every word it shares and whose principles are in total harmony with the commitments made by the company and the values that have guided it over the years. Adherence to the LVMH Code of Conduct is an opportunity and an incentive to further strengthen all the operating guidelines and systems that we have developed over the years, guaranteeing coherence between business values and activities. Bulgari is committed to guaranteeing compliance with the principles set out in the LVMH Code of Conduct and ensuring that they are implemented and disseminated. -

Pan-European Footfall 2017-2018

REAL ESTATE PAN-EUROPEANFOR A CHANGING WORLD FOOTFALL ANALYSIS Key global and lifestyle cities 2017-2018 PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT TRANSACTION CONSULTING VALUATION PROPERTY MANAGEMENT INVESTMENTRETAIL MANAGEMENT Real EstateReal Estate forfor a a changing changing world world CONTENT Macroeconomics ............ 04 Amsterdam .......................... 30 Helsinki ...................................... 46 Warsaw ...................................... 62 Synthesis ................................... 06 Athens ......................................... 32 Lisbon ........................................... 48 Zurich ............................................ 64 Barcelona ................................ 34 Munich ........................................ 50 London ........................................ 10 Brussels ..................................... 36 Oslo ................................................. 52 Methodology ........................ 67 Paris ................................................ 14 Budapest ................................. 38 Prague ......................................... 54 Results by country ........ 68 Madrid ........................................ 18 Copenhagen ....................... 40 Rome ............................................. 56 Contacts ..................................... 70 Milan .............................................. 22 Dublin ........................................... 42 Stockholm .............................. 58 Berlin ............................................. 26 Frankfurt .................................. -

Commercial Real Estate in the Paris Region Results & Outlook

Commercial Real Estate in the Paris Region Results & Outlook PARIS VISION 2016 1 and now, presenting... THE BIG CATCH-UP Dear friends, We saw a slow start to 2015, with transaction volumes falling sharply at the beginning of the first half of the year. The second half swept away uncertainties by making up much of the lost ground. The office rental market demonstrated its resilience and even a certain dynamism in small- and medium- sized area segments, proof that SMEs are more positive and looking to the future with confidence. The investment market meanwhile recorded its third best year of the decade after 2007. Real estate is currently a particularly popular asset class with investors and a considerable mass of liquidity is flowing into the Greater Paris region market and impacting yields – which are at a record low. Will the market be able to absorb this demand? Is the rental market at the start of a new cycle driven by more PHILIPPE PERELLO robust growth as Daniel Cohen predicts? CEO Paris Office Partner Knight Frank LLP These are some of the questions we have attempted to answer with the insights of our main contributors – Jean-Philippe Olgiati (Blackrock), François Darsonval (Publicis), Laurent Fléchet (Primonial) and Pierre Dubail (Dubail Rolex) – each of them key market players who offer us their analysis. For that, I would like to offer them my heartfelt thanks. PARIS VISION 2016 CONTENTS opinion Daniel Cohen 6 vision the jean-philippe olgiati 8 Magicians THE OFFICE LETTING MARKET TRENDS 11 OUTLOOK 24 QUESTIONS TO: François Darsonval 30 flashback 50 PARIS VISION 2016 the animal trapeze tamers artists THE INVESTMENT MARKET THE RETAIL MARKET TRENDS 33 TRENDS 55 OUTLOOK 44 OUTLOOK 70 QUESTIONS TO: Laurent Fléchet 48 QUESTIONS TO: Pierre Dubail 74 2015 key figure 52 knight frank 76 6 opinion Daniel cohen Professor and Director of the Economics Department of Higher Normal School (École Normale Supérieure de Paris) Founding member of the École d'Économie de Paris Director of CEPREMAP (Centre pour la recherche Économique et des Applications). -

Press Release 2021 LVMH PRIZE for YOUNG FASHION DESIGNERS: 8TH EDITION

Press release 2021 LVMH PRIZE FOR YOUNG FASHION DESIGNERS: 8TH EDITION LVMH ANNOUNCES THE LIST OF THE 9 FINALISTS Paris, 28th April 2021 The semi-final of the LVMH Prize took place from 6th to 11th April 2021. Twenty young designers selected among the 1,900 candidates from all over the world presented their collections on the digital platform lvmhprize.com. The committee of Experts of the Prize and, for the first time, the public as a new Expert, selected 9 brands for the final. These 9 designers will present their creations to the Jury on the occasion of the final which will be held in September at the Louis Vuitton Foundation, on a date to be announced later. The Jury of the LVMH Prize will choose the winners of the LVMH Prize and of the Karl Lagerfeld / Special Jury Prize among the finalists. The 9 finalists are: BIANCA SAUNDERS by Bianca Saunders (British designer based in London), menswear CHARLES DE VILMORIN by Charles de Vilmorin (French designer based in Paris) genderless collections CHRISTOPHER JOHN ROGERS by Christopher John Rogers (American designer based in New York), womenswear CONNER IVES by Conner Ives (American designer based in London), womenswear KIDSUPER by Colm Dillane (American designer based in New York), menswear KIKA VARGAS by Kika Vargas (Colombian designer based in Bogota), womenswear LUKHANYO MDINGI by Lukhanyo Mdingi (South African designer based in Cape Town), womenswear and menswear NENSI DOJAKA by Nensi Dojaka (Albanian designer based in London), womenswear RUI by Rui Zhou (Chinese designer based in Shanghai), genderless collections Delphine Arnault declares: "The all-digital semi-final this year, in the context of the health crisis, was a new opportunity to showcase the work of the designers. -

Vogue on Christian Dior

Dior’s monochromatic Mexique dress from 1951. Photograph Henry Clarke. A René Bouché sketch of Dior’s 1949 cocktail dress with sweeping floor sash. Dior photographed by Henry Clarke for Vogue with his favorite model, Renée, in 1957. Contents FORTUNE’S FAVOR NEW LOOK CHANGING SEASONS COMPLETELY DIOR DIOR’S LEGACY Index of Searchable Terms References Picture credits Acknowledgments “OF COURSE FASHION IS A TRANSIENT, EGOTISTICAL INDULGENCE, YET IN AN ERA AS SOMBRE AS OURS, LUXURY MUST BE DEFENDED CENTIMETRE BY CENTIMETRE.” CHRISTIAN DIOR FORTUNE’S FAVOR F YOU CONJURED AN IMAGE of a fashion designer in your mind, you mIight not settle on one who looked like Christian Dior. A man “with an air of baby plumpness still about him and an almost desperate shyness augmented by a receding chin” as American Vogue’s Bettina Ballard recalled in 1946. Or the “plump, balding bachelor of fifty-two whose pink cheeks might have been sculpted from marzipan,” as described by Time reporter Stanley Karnow in 1957. The same sugary confection found its way into the great photographer Cecil Beaton’s account of Dior: “a bland country curate made out of pink marzipan.” Not that Christian Dior was unaware of the shortfall in his appearance. He wrote, “I could not help thinking that I cut a sorry figure – a well-fed gentleman in the Parisian’s favourite neutral-coloured suit – compared with the glamour, not to say dandified or effeminate couturier of popular imagination.” Dior was a man who knew what a legend should look like. Photographed for Vogue on February 12, 1947—the day his New Look was launched upon the world—Dior is pictured dressed in sepulchral black, markedly glum, giving credence to his description in Life magazine as “a French Undertaker.” In the photograph the designer looks anything but legendary, anxiety writ large in the downturn of his mouth, in his distracted, sidelong gaze. -

Plaza Athénée Paris: Service Innovation in a Luxury Hotel

Plaza Athénée Paris: Service Innovation in a Luxury Hotel Michel PHAN - ESSEC Business School Plaza Athénée Paris: Service Innovation in a Luxury Hotel This case study was written by Michel Phan (ESSEC Business School). This case study shows how the Plaza Athénée Paris, a French luxury hotel of the Dorchester Group, has emerged over the years as a reference in service innovation. Via the case, you will discover the successful innovation process used and the secrets of this success: strong management leadership, a shared corporate culture, an adapted organisational structure, and a family of highly-motivated employees. The key challenge for the hotel remains the maintenance of its leadership in terms of service innovation for the years to come without compromising its identity. OVERVIEW OF THE CASE “Once up on a time, the palace of tomorrow…” The Plaza Athénée Paris is a French luxury hotel (also commonly called “a palace” in France) located at 25, Avenue Montaigne, one of the most prestigious addresses in Paris and synonymous with luxury at its best. Strolling along the Avenue Montaigne, luxury shoppers can find most of the well-known luxury brands in fashion, watches, leather goods and jewellery, from Gucci at one end of the avenue to Prada at the other end with Chanel, Dior, Louis Vuitton, Harry Winston or Bulgari in between. This case study relates to how the Plaza Athénée Paris has become a reference in the luxury hotel sector in terms of service innovations. The secrets of its success are: a corporate culture that encourages innovation and change, a strong management leadership, a perfectly adapted organisational structure and a ‘family’ of well-motivated employees. -

Press Release

Press release Stella McCartney and LVMH announce a new partnership to further develop the Stella McCartney House Paris, July 15th, 2019 Stella McCartney and LVMH have reached an agreement to further develop the Stella McCartney House. The new partners will detail the full scope of this deal in September. Ms Stella McCartney will of course continue as creative director and ambassador of her brand, while holding majority ownership. The goal of this partnership will be for the Stella McCartney House to accelerate its worldwide development in terms of business and strategy, while of course remaining faithful to its long-lasting commitment to sustainable and ethical luxury fashion. Ms Stella McCartney will hold a specific position and role on sustainability as special advisor to Mr. Arnault and the executive committee members. LVMH and Stella McCartney are delighted to open this new chapter together. Bernard Arnault, Chairman and CEO of LVMH, declared: “I am extremely happy with this partnership with Stella. It is the beginning of a beautiful story together, and we are convinced of the great long-term potential of her House. A decisive factor was that she was the first to put sustainability and ethical issues on the front stage, very early on, and built her House around these issues. It emphasizes LVMH Groups’ commitment to sustainability. LVMH was the first large company in France to create a sustainability department, more than 25 years ago, and Stella will help us further increase awareness on these important topics.” Ms Stella McCartney added: “Since the announcement of my decision to take full ownership of the Stella McCartney brand in March 2018 there have been many approaches from various parties expressing their wish to partner and invest in the Stella McCartney House. -

Retail Property Market in France

2018 Review & 2019 Outlook RETAIL RETAIL PROPERTY MARKET FRANCE THE RETAIL PROPERTY MARKET Overview ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT RETAILERS / PRODUCTS LETTINGS INVESTMENT • The gilets jaunes (“yellow • High-tech products • Retailers continue to • In 2018, investment in vests”) movement has continue to expand. prefer the busiest the French retail market exacerbated the French Other sectors driving the locations in Paris and came to €4.4 billion. This economic slowdown and market are sporting goods other large cities. amount is up slightly year hurt retail business in and leisure, household on year, thanks to a very Paris and other cities goods and interior décor, • Retailer vitality depends good fourth quarter and around France. and food-restaurants. on the appeal of specific the sale of two Monoprix cities. portfolios for more than • While inflation is expected • Discount chains also €750 million. to subside in 2019, and continue to expand, just • However, cost-cutting measures designed to as web-based brands. property strategies are • In all, there were 11 boost purchasing power now common to all transactions of more may increase consumer • With sales slowing, regions, and they continue than €100 million in spending, much depends fashion retailers are now to weigh on rental values. 2018, accounting for 55% on which way the social focused on cost-cutting of total investment in climate goes. measures. Zara and H&M • Retail closings and France. create spectacular stores openings occur with • Although demonstrations which provide an ever- greater rapidity as more • This trend has profited at the end of the year increasing range of tests, new locations, and mainly high streets (60% resulted in a decline in services, while sacrificing pop-up stores gain of investments), ahead of international tourist non-strategic sales points. -

Passionate About Creativity

2020 ANNUAL REPORT Passionate about creativity Passionate about creativity THE LVMH SPIRIT Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy merged in 1987, creating the LVMH Group. From the outset, Bernard Arnault gave the Group a clear vision: to become the world leader in luxury, with a philosophy summed up in its motto, “Passionate about creativity”. Today, the LVMH Group comprises 75 exceptional Maisons, each of which creates products that embody unique craftsmanship, carefully preserved heritage and resolute modernity. Through their creations, the Maisons are the ambassadors of a refined, contemporary art de vivre. LVMH nurtures a family spirit underpinned by an unwavering long-term corporate vision. The Group’s vocation is to ensure the development of each of its Maisons while respecting their identity and their autonomy, by providing all the resources they need to design, produce and distribute their creations through carefully selected channels. Our Group and Maisons put heart and soul into everything they do. Our core identity is based on the fundamental values that run through our entire Group and are shared by all of us. These values drive our Maisons’ performance and ensure their longevity, while keeping them attuned to the spirit of the times and connected to society. Since its inception, the Group has made sustainable development one of its strategic priorities. Today, this policy provides a powerful response to the issues of corporate ethical responsibility in general, as well as the role a group like LVMH should play within French society and internationally. Our philosophy: Passionate about creativity THE VALUES OF A DEEPLY COMMITTED GROUP Being creative and innovative Creativity and innovation are part of LVMH’s DNA; throughout the years, they have been the keys to our Maisons’ success and the basis of their solid reputations.