The Music of John Luther Adams / Edited by Bernd Herzogenrath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voice Phenomenon Electronic

Praised by Morton Feldman, courted by John Cage, bombarded with sound waves by Alvin Lucier: the unique voice of singer and composer Joan La Barbara has brought her adventures on American contemporary music’s wildest frontiers, while her own compositions and shamanistic ‘sound paintings’ place the soprano voice at the outer limits of human experience. By Julian Cowley. Photography by Mark Mahaney Electronic Joan La Barbara has been widely recognised as a so particularly identifiable with me, although they still peerless interpreter of music by major contemporary want to utilise my expertise. That’s OK. I’m willing to composers including Morton Feldman, John Cage, share my vocabulary, but I’m also willing to approach a Earle Brown, Alvin Lucier, Robert Ashley and her new idea and try to bring my knowledge and curiosity husband, Morton Subotnick. And she has developed to that situation, to help the composer realise herself into a genuinely distinctive composer, what she or he wants to do. In return, I’ve learnt translating rigorous explorations in the outer reaches compositional tools by apprenticing, essentially, with of the human voice into dramatic and evocative each of the composers I’ve worked with.” music. In conversation she is strikingly self-assured, Curiosity has played a consistently important role communicating something of the commitment and in La Barbara’s musical life. She was formally trained intensity of vision that have enabled her not only as a classical singer with conventional operatic roles to give definitive voice to the music of others, in view, but at the end of the 1960s her imagination but equally to establish a strong compositional was captured by unorthodox sounds emanating from identity owing no obvious debt to anyone. -

Lilypond Music Glossary

LilyPond The music typesetter Music Glossary The LilyPond development team ☛ ✟ This glossary provides definitions and translations of musical terms used in the documentation manuals for LilyPond version 2.23.3. ✡ ✠ ☛ ✟ For more information about how this manual fits with the other documentation, or to read this manual in other formats, see Section “Manuals” in General Information. If you are missing any manuals, the complete documentation can be found at http://lilypond.org/. ✡ ✠ Copyright ⃝c 1999–2021 by the authors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. For LilyPond version 2.23.3 1 1 Musical terms A-Z Languages in this order. • UK - British English (where it differs from American English) • ES - Spanish • I - Italian • F - French • D - German • NL - Dutch • DK - Danish • S - Swedish • FI - Finnish 1.1 A • ES: la • I: la • F: la • D: A, a • NL: a • DK: a • S: a • FI: A, a See also Chapter 3 [Pitch names], page 87. 1.2 a due ES: a dos, I: a due, F: `adeux, D: ?, NL: ?, DK: ?, S: ?, FI: kahdelle. Abbreviated a2 or a 2. In orchestral scores, a due indicates that: 1. A single part notated on a single staff that normally carries parts for two players (e.g. first and second oboes) is to be played by both players. -

Theory of Music

MUSIC THEORY 1. Staffs, Clefs & Pitch notation Naming the Notes Musical notation describes the pitch (how high or low), temporal position (when to start) and duration (how long) of discrete elements, or sounds, we call notes . The notes are represented by graphical symbols, also called notes or note signs . In English-speaking countries, the pitch names given to a row of notes steadily rising in pitch are drawn from the the first seven letters of the Roman alphabet: A B C D E F G In the Netherlands, the letters A to G are also used, but otherwise the 'Dutch' system follows the 'German' system, so-called because it originated in Germany, which also uses H. Staff or Stave The note signs are placed on a grid formed of horizontal lines and spaces. This grid is called the staff or stave . The plural of either word is staves . Although, in the past, staves could have many different numbers of lines, today the most common staff format has five lines separated by four spaces and is know as the pentagram . When numbering the lines, it is a widely used convention to number them from the bottom ( 1) to the top ( 5) of each staff. The spaces between the lines are numbered too, again from the bottom ( 1) to the top ( 4). Redaction and Publishing Marzenna Donajski © Dolmetsch Music Theory and History Online by Dr. Brian Blood 1 Music is read from 'left' to 'right', in the same direction as you are reading this text. The higher the pitch of the note , the higher vertically the note will be placed on the staff . -

O Desconcerto Anarquista De John Cage

Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Ciências Sociais Gustavo Ferreira Simões o desconcerto anarquista de john cage Doutorado em Ciências Sociais São Paulo 2017 ! Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Ciências Sociais Gustavo Ferreira Simões o desconcerto anarquista de john cage Tese apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências Sociais sob orientação do Prof. Dr. Edson Passetti. São Paulo 2017 ! ______________________ ______________________ ______________________ ______________________ ______________________ ! RESUMO Em 1988, John Cage inventou Anarchy , livro em que, a partir de escritos experimentais, valorizou as vidas de mulheres e homens anarquistas que marcaram seu percurso ético-estético libertário desde meados dos anos 1940 até a década de 1990, quando em seus últimos trabalhos, “number pieces” (1987-1992), apresentou o que denominou “harmonia anárquica”. Foi a partir da coexistência com artistas e militantes na Black Mountain College, no final da década de 1940, assim como em Nova York com o The Living Theatre (TLT) , que o artista já conhecido por seu corajoso “piano preparado” passou a elaborar o anarquismo como prática de vida. “4’33” (1952), ação direta contra a representação musical dos sons e em favor da incorporação dos ruídos excluídos pelas salas de concerto, irrompeu empolgada por essa aproximação libertária. Nas décadas seguintes, vivendo ao lado de artistas e anarquistas, afastado da cidade, em Stonypoint, iniciou a publicação de how to improve the world (you only make matters worse) (1965-1982), diário mantido por mais de quinze anos e no qual apresentou a lida com os escritos de Henry David Thoreau, preocupações antimilitares e ecológicas. -

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

Lierbergercollege of Fine Arts

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ASU Digital Repository SONIC GEOGRAPHY THE MUSIC OF JOHN LUTHER ADAMS ACME GLENN HACKBARTH, DIRECTOR STUDENT ENSEMBLE RECITAL SERIES KATZIN CONCERT HALL FRIDAY, APRIL 27, 2007 7:30 PM MUSIC lierbergerCollege of Fine Arts ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Program The Light That Fills the World Sarah Bowlin, violin Christopher Rose, bass Bill Sallak and Matt Coleman, percussion Jennifer Waleczek and Patrick Fanning, synthesizer Eric Schultz, sound ...and bells remembered... Bill Sallak, Jesse Parker, Yi-Chia Chen, Darrell Thompson, Matt Coleman, percussion Eric Schultz, conductor Dark Waves Jennifer Waleczek and Patrick Fanning, piano Eric Schultz, sound **There will be a 10-minute intermission** Dark Wind Josh Bennett, bass clarinet Yi-Chia Chen and Jesse Parker, percussion Patrick Fanning, piano James Smart, conductor Red Arc/Blue Veil Yi-Chia Chen, percussion Jennifer Waleczek, piano Eric Schultz, sound Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. ittyRE Performance Events Staff Manager Paul W. Estes Senior Event Mangers: Iftekhar, Anwar, Laura Boone, Edwin Brown, Brady Cullum, Eric Damashek, Mirel DeLaTorre, Anthony Garcia, Ingrid Israel Xian Meng, Kevan Nymeyer Apprentice Event Managers: Lee E. Humphrey, Megan Leigh Smith Events Information Call 480-965-TUNE (480-965-8863) 02006 ASU Herberger College of Fine Arts 0706. -

An African-American Contribution to the Percussion Literature in the Western Art Music Tradition

Illuminating Silent Voices: An African-American Contribution to the Percussion Literature in the Western Art Music Tradition by Darrell Irwin Thompson A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved April 2012 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Mark Sunkett, Chair Bliss Little Kay Norton James DeMars Jeffrey Bush ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2012 ABSTRACT Illuminating Silent Voices: An African-American Contribution to the Percussion Literature in the Western Art Music Tradition will discuss how Raymond Ridley's original composition, FyrStar (2009), is comparable to other pre-existing percussion works in the literature. Selected compositions for comparison included Darius Milhaud's Concerto for Marimba, Vibraphone and Orchestra, Op. 278 (1949); David Friedman's and Dave Samuels's Carousel (1985); Raymond Helble's Duo Concertante for Vibraphone and Marimba, Op. 54 (2009); Tera de Marez Oyens's Octopus: for Bass Clarinet and one Percussionist (marimba/vibraphone) (1982). In the course of this document, the author will discuss the uniqueness of FyrStar's instrumentation of nine single reed instruments--E-flat clarinet, B-flat clarinet, alto clarinet, bass clarinet, B-flat contrabass clarinet, B-flat soprano saxophone, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, and B-flat baritone saxophone, juxtaposing this unique instrumentation to the symbolic relationship between the ensemble, marimba, and vibraphone. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I first want to thank God, for guiding my thoughts, hands, and feet. I am grateful, for the support, understanding, and guidance I have received from my parents. I also want to thank my grandmother, sister, brother, and to the rest of my family for being one of the best support groups anyone could have. -

2020-21-Brochure.Pdf

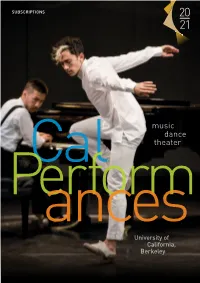

SUBSCRIPTIONS 20 21 music dance Ca l theater Performances University of California, Berkeley Letter from the Director Universities. They exist to foster a commitment to knowledge in its myriad facets. To pursue that knowledge and extend its boundaries. To organize, teach, and disseminate it throughout the wider community. At Cal Performances, we’re proud of our place at the heart of one of the world’s finest public universities. Each season, we strive to honor the same spirit of curiosity that fuels the work of this remarkable center of learning—of its teachers, researchers, and students. That’s why I’m happy to present the details of our 2020/21 Season, an endlessly diverse collection of performances rivaling any program, on any stage, on the planet. Here you’ll find legendary artists and companies like cellist Yo-Yo Ma, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra with conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the Mark Morris Dance Group, pianist Mitsuko Uchida, and singer/songwriter Angélique Kidjo. And you’ll discover a wide range of performers you might not yet know you can’t live without—extraordinary, less-familiar talent just now emerging on the international scene. This season, we are especially proud to introduce our new Illuminations series, which aims to harness the power of the arts to address the pressing issues of our time and amplify them by shining a light on developments taking place elsewhere on the Berkeley campus. Through the themes of Music and the Mind and Fact or Fiction (please see the following pages for details), we’ll examine current groundbreaking work in the university’s classrooms and laboratories. -

Alvin Lucier's

CHAMBERS This page intentionally left blank CHAMBERS Scores by ALVIN LUCIER Interviews with the composer by DOUGLAS SIMON Wesleyan University Press Middletown, Connecticut Scores copyright © 1980 by Alvin Lucier Interviews copyright © 1980 by Alvin Lucier and Douglas Simon Several of these scores and interviews have appeared in similar or different form in Arts in Society; Big Deal; The Painted Bride Quar- terly; Parachute; Pieces 3; The Something Else Yearbook; Source Magazine; and Individuals: Post-Movement Art in America, edited by Alan Sondheim (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1977). Typography by Jill Kroesen The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of a Wesleyan University Project Grant. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lucier, Alvin. [Works. Selections] Chambers. Concrete music. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Concrete music. 2. Chance compositions. 3. Lucier, Alvin. 4. Composers—United States- Interviews. I. Simon, Douglas, 1947- II. Title. M1470.L72S5 789.9'8 79-24870 ISBN 0-8195-5042-6 Distributed by Columbia University Press 136 South Broadway, Irvington, N.Y. Printed in the United States of America First edition For Ellen Parry and Wendy Stokes This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS Preface ix 1. Chambers 1 2. Vespers 15 3. "I Am Sitting in a Room" 29 4. (Hartford) Memory Space 41 5. Quasimodo the Great Lover 53 6. Music for Solo Performer 67 7. The Duke of York 79 8. The Queen of the South and Tyndall Orchestrations 93 9. Gentle Fire 109 10. Still and Moving Lines of Silence in Families of Hyperbolas 127 11. Outlines and Bird and Person Dyning 145 12. -

WHAT USE IS MUSIC in an OCEAN of SOUND? Towards an Object-Orientated Arts Practice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR WHAT USE IS MUSIC IN AN OCEAN OF SOUND? Towards an object-orientated arts practice AUSTIN SHERLAW-JOHNSON OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY Submitted for PhD DECEMBER 2016 Contents Declaration 5 Abstract 7 Preface 9 1 Running South in as Straight a Line as Possible 12 2.1 Running is Better than Walking 18 2.2 What You See Is What You Get 22 3 Filling (and Emptying) Musical Spaces 28 4.1 On the Superficial Reading of Art Objects 36 4.2 Exhibiting Boxes 40 5 Making Sounds Happen is More Important than Careful Listening 48 6.1 Little or No Input 59 6.2 What Use is Art if it is No Different from Life? 63 7 A Short Ride in a Fast Machine 72 Conclusion 79 Chronological List of Selected Works 82 Bibliography 84 Picture Credits 91 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. Name: Austin Sherlaw-Johnson Signature: Date: 23/01/18 Abstract What Use is Music in an Ocean of Sound? is a reflective statement upon a body of artistic work created over approximately five years. This work, which I will refer to as "object- orientated", was specifically carried out to find out how I might fill artistic spaces with art objects that do not rely upon expanded notions of art or music nor upon explanations as to their meaning undertaken after the fact of the moment of encounter with them. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Interpreting Henri Dutilleux’s Quotations of Baudelaire in "Tout un monde lointain..." Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0tz887wb Author Tyler, Charles Robert Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Interpreting Henri Dutilleux’s Quotations of Baudelaire in Tout un monde lointain… A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts by Charles Robert Tyler 2016 © Copyright by Charles Robert Tyler 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Interpreting Henri Dutilleux’s Quotations of Baudelaire in Tout un monde lointain… by Charles Robert Tyler Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Antonio Lysy, Chair Henri Dutilleux (1916-2013) is one of the most significant and widely acclaimed composers of the last century. Dutilleux is best known for his approach towards orchestral timbre and color and his works exhibit an individual style that defies classification. This dissertation will be dedicated to exploring the interpretive issues presented in Henri Dutilleux’s composition for cello and orchestra, Tout un monde lointain… The quotations taken from Baudelaire’s poetry found in this score above each movement leave the performer with many unanswered interpretive questions. Through researching Dutilleux’s use of quotation in other scores, examining the intricacies of Baudelaire’s poetry and considering the existing publications pertaining to his concerto, one will be considerably better equipped to answer the varying questions sense of mystery raised by these quotations. Such analysis will aid one in interpreting and executing his concerto with a heightened understanding of Dutilleux’s musical language within the aesthetics and context he provides through his quotations of Baudelaire.