The House Rules? International Lessons for Enhancing The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Report

HOUSE OF LORDS Procedure and Privileges Committee 2nd Report of Session 2021–22 Sitting times of Grand Committees Timetabling of Thursday debates Legislative Consent Motions for Lords Private Members’ Bills Ordered to be printed 29 July 2021 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords HL Paper 61 Procedure and Privileges Committee The Select Committee on Procedure and Privileges of the House is appointed each session to consider any proposals for alterations in the procedure of the House that may arise from time to time, and whether the standing orders require to be amended. Membership The members of the Procedure and Privileges Committee are: Lord Ashton of Hyde Lord McAvoy Lord Bew Lord McFall of Alcluith (Lord Speaker) Lord Eames Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall Baroness Evans of Bowes Park Lord Newby Lord Faulkner of Worcester Baroness Quin Lord Gardiner of Kimble (Chair) Baroness Smith of Basildon Lord Geddes Lord Stoneham of Droxford Baroness Harris of Richmond Baroness Thomas of Winchester Lord Judge Viscount Ullswater Lord Mancroft Alternate members: Baroness Browning (for backbench Conservative members) Baroness Finlay of Llandaff (for Crossbench members, other than the Convenor) Baroness Goudie (for backbench Labour members) Lord Alderdice (for backbench Liberal Democrat members) Lord Turnbull (for the Convenor) Declaration of interests A full list of Members’ interests can be found in the Register of Lords’ Interests: http://www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/standards-and-interests/register-of-lords- interests/ Publications -

Katherine Kerswell Chief Executive London Borough of Croydon Bernard Weatherill House 8 Mint Walk Croydon CR0 1EA

Katherine Kerswell Chief executive London Borough of Croydon Bernard Weatherill House 8 Mint Walk Croydon CR0 1EA December 17th Dear Katherine Kerswell, Initially, I wrote to Croydon Council on the 27th July to raise concerns about the impact of the LTN scheme. I also spoke to the former Croydon Cabinet Member for transport and expressed my deep concerns with the scheme, as well as having written to the Secretary of State for Transport to raise my concerns and request any further assistance he can provide. Unfortunately, this matter remains a major issue locally - my constituents have continued to be impacted with reports of increased road rage, traffic and road closures. London Borough of Bromley challenged the legality of the LTN scheme, due to the failure of Croydon to consult with LBB before implementing the scheme. I welcomed the news that Croydon Council allowed a formal consultation on the final agreed proposals, allowing residents to comment formally on the proposals. However, I was disappointed to have been informed last week that the consultation was extended by another 14 days as local businesses were not included in the first consultation. It is right that local businesses are consulted, but I had hoped that this would have been done at the outset. The consultation, therefore, ends on Friday and the outcome will not be known until early January causing further delay and distress to those affected. My view remains unchanged, I believe that if a better scheme can work for both Boroughs, it should be trialled first. If this isn’t possible then the current roadblocks should be voted out and the idea abandoned as it simply has not worked in practice. -

Westminster Abbey a Service for the New Parliament

St Margaret’s Church Westminster Abbey A Service for the New Parliament Wednesday 8th January 2020 9.30 am The whole of the church is served by a hearing loop. Users should turn the hearing aid to the setting marked T. Members of the congregation are kindly requested to refrain from using private cameras, video, or sound recording equipment. Please ensure that mobile telephones and other electronic devices are switched off. The service is conducted by The Very Reverend Dr David Hoyle, Dean of Westminster. The service is sung by the Choir of St Margaret’s Church, conducted by Greg Morris, Director of Music. The organ is played by Matthew Jorysz, Assistant Organist, Westminster Abbey. The organist plays: Meditation on Brother James’s Air Harold Darke (1888–1976) Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’ BWV 678 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) The Lord Speaker is received at the East Door. All stand as he is conducted to his seat, and then sit. The Speaker of the House of Commons is received at the East Door. All stand as he is conducted to his seat, and then sit. 2 O R D E R O F S E R V I C E All stand to sing THE HYMN E thou my vision, O Lord of my heart, B be all else but naught to me, save that thou art, be thou my best thought in the day and the night, both waking and sleeping, thy presence my light. Be thou my wisdom, be thou my true word, be thou ever with me, and I with thee, Lord; be thou my great Father, and I thy true son, be thou in me dwelling, and I with thee one. -

Report of the Select Committee on the Reduction of Standing Committees of Tynwald

REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE REDUCTION OF STANDING COMMITTEES OF TYNWALD t i I. • REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE REDUCTION OF STANDING COMMITTEES OF TYNWALD To the Honourable Noel Q Cringle, President of Tynwald, and the Honourable Members of the Council and Keys in Tynwald assembled PART 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Background At the sitting of Tynwald Court on 21st May 2002 it was resolved that a Select Committee of five members be established to - "investigate and report by no later than July 2003 on the feasibility of reducing the number of Standing Committees of Tynwald along with any recommendations as to the responsibilities and membership and any proposals for change." 2. Mr Karran, Mr Lowey, Mr Quayle, Mr Quine and Mr Speaker were elected. At 4, the first meeting Mr Speaker was unanimously elected as Chairman. 3. The Committee has held four meetings. C/RSC/02/plb PART 2 STRATEGY 2.1 The Committees of Tynwald that would be examined were determined as: Committee on Constitutional Matters; Committee on the Declaration of Members' Interests, Ecclesiastical Committee; Committee on Economic Initiatives; Joint Committee on the Emoluments of Certain Public Servants; Committee on Expenditure and Public Accounts; Tynwald Ceremony Arrangements Committee; Tynwald Honours Committee; Tynwald Management Committee; Tynwald Members' Pension Scheme Management Committee; and Tynwald Standing Orders Committee of Tynwald. A brief summary of the membership and terms of reference of each standing committee is attached as Appendix 1. 2 C/RSC/02/plb 2.2 In order to facilitate its investigation your Committee also decided that - (a) Comparative information on committee structures in adjacent parliaments should be obtained. -

Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1328-7478 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship Sarah Miskin Politics and Public Administration Group 24 March 2003 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Martin Lumb and Janet Wilson for their help with the research into party defections in Australia and Cathy Madden, Scott Bennett, David Farrell and Ben Miskin for reading and commenting on early drafts. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

House of Representatives Practice

15 Questions One of the more important functions of the House is its critical review function. This includes scrutiny of the Executive Government, bringing to light issues and perceived deficiencies or problems, ventilating grievances, exposing, and thereby preventing the Government from exercising, arbitrary power, and pressing the Government to take remedial or other action. Questions are a vital element in this function. It is fundamental in the concept of responsible government that the Executive Government be accountable to the House. The capacity of the House of Representatives to call the Government to account depends, in large measure, on its knowledge and understanding of the Government’s policies and activities. Questions without notice and on notice (questions in writing) play an important part in this quest for information. QUESTION TIME The accountability of the Government is demonstrated most clearly and publicly at Question Time when, for a period (currently usually over an hour) on most sitting days, questions without notice are put to Ministers.1 The importance of Question Time is demonstrated by the fact that at no other time in a normal sitting day is the House so well attended. Question Time is usually an occasion of special interest not only to Members themselves but to the news media, the radio and television broadcast audience and visitors to the public galleries. It is also a time when the intensity of partisan politics can be clearly manifested. The purpose of questions is ostensibly to seek information or press for action.2 However, because public attention focuses so heavily on Question Time it is often a time for political opportunism. -

Parliamentary Scorecard 2009 – 2010

PARLIAMENTARY SCORECARD 2009 – 2010 ASSESSING THE PERFORMANCE OF UGANDA’S LEGISLATORS Parliamentary Scorecard 2009 – 2010: Assessing the Performance of Uganda’s Legislators A publication of the Africa Leadership Institute with technical support from Projset Uganda, Stanford University and Columbia University. Funding provided by the Royal Netherlands Embassy in Uganda and Deepening Democracy Program. All rights reserved. Published January 2011. Design and Printing by Some Graphics Ltd. Tel: +256 752 648576; +256 776 648576 Africa Leadership Institute For Excellence in Governance, Security and Development P.O. Box 232777 Kampala, Uganda Tel: +256 414 578739 Plot 7a Naguru Summit View Road Email: [email protected] 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Acknowledgements 3 II. Abbreviations 6 III. Forward 7 IV. Executive Summary 9 V. Report on the Parliamentary Performance Scorecard 13 1. Purpose 13 2. The Road to the 2009 – 2010 Scorecard 14 2.1 Features of the 2009 – 2010 Scorecard 15 3. Disseminating the Scorecard to Voters through Constituency Workshops 17 4. Data Sources 22 5. Measures 22 A. MP Profile 23 B. Overall Grades for Performance 25 C. Disaggregated Performance Scores 29 Plenary Performance 29 Committee Performance 34 Constituency Performance 37 Non-Graded Measures 37 D. Positional Scores 40 Political Position 40 Areas of Focus 42 MP’s Report 43 6. Performance of Parliament 43 A. Performance of Sub-Sections of Parliament 43 B. How Does MP Performance in 2009 – 2010 Compare to Performance in the Previous Three Years of the 8th Parliament? 51 Plenary Performance 51 Committee Performance 53 Scores Through the Years 54 C. Parliament’s Productivity 55 7. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 25 August 2015 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Not peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Johnson, Rachel E. and Armitage, Faith and Spary, Carole and Malley, Rosa (2012) 'A conversation : researching gendered ceremony and ritual in parliaments.', Feminist theory., 13 (3). pp. 325-336. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1464700112456007 Publisher's copyright statement: Johnson, Rachel E. and Armitage, Faith and Spary, Carole and Malley, Rosa (2012) 'A conversation : researching gendered ceremony and ritual in parliaments.', Feminist theory., 13 (3). pp. 325-336. Copyright c 2012 The Author(s). Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Feminist Theory, Vol. 13, Issue 3, pp.325-336. Researching Gendered Ceremony and Ritual in Parliaments In June 2009, John Bercow presided over the British House of Commons in his first session as Speaker. -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

Hong Kong British National (Overseas) Visa 4

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8939, 5 May 2021 Hong Kong British By Melanie Gower National (Overseas) visa Esme Kirk-Wade Contents: 1. Background to British National (Overseas) status 2. Calls to extend BN(O) immigration and citizenship rights 3. The new Hong Kong British National (Overseas) visa 4. The BN(O) visa: topical issues www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Hong Kong British National (Overseas) visa Contents Summary 3 1. Background to British National (Overseas) status 5 1.1 Acquiring BN(O) status: legislation 5 1.2 Immigration and citizenship rights historically conferred by BN(O) status 6 2. Calls to extend BN(O) immigration and citizenship rights 10 2.1 Until May 2020 10 2.2 Summer 2020: Announcement of a new visa route for BN(O)s 11 2.3 Ten Minute Rule Bill: Hong Kong Bill 2019-21 13 3. The new Hong Kong British National (Overseas) visa 14 3.1 Policy, legislation and guidance 14 3.2 Practical details 14 3.3 More generous terms than other visa categories? 18 4. The BN(O) visa: topical issues 19 4.1 How many people might come to the UK? 19 4.2 Integration support and managing the impact on local areas 19 4.3 The gaps in the UK’s offer 21 4.4 What are other countries doing? 21 Cover page image copyright Attribution: Chinese demonstrators, 2019– 20 Hong Kong protests by Studio Incendo – Wikimedia Commons page. Licensed by Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) / image cropped. -

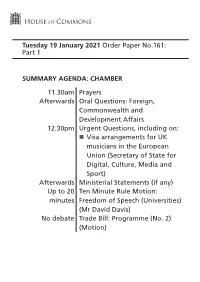

Order Paper for Tue 19 Jan 2021

Tuesday 19 January 2021 Order Paper No.161: Part 1 SUMMARY AGENDA: CHAMBER 11.30am Prayers Afterwards Oral Questions: Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs 12.30pm Urgent Questions, including on: Visa arrangements for UK musicians in the European Union (Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport) Afterwards Ministerial Statements (if any) Up to 20 Ten Minute Rule Motion: minutes Freedom of Speech (Universities) (Mr David Davis) No debate Trade Bill: Programme (No. 2) (Motion) 2 Tuesday 19 January 2021 OP No.161: Part 1 Up to four Trade Bill: Consideration of Lords hours* Amendments *(if the Trade Bill: Programme (No. 2) (Motion) is agreed to) Until any Business of the House (High hour** Speed Rail (West Midlands - Crewe) Bill) (Motion) **(if the 7.00pm Business of the House Motion is agreed to) Up to one High Speed Rail (West Midlands hour from - Crewe) Bill: Consideration of commencement Lords Amendments of proceedings ***(if the Business of the House on the Business (High Speed Rail (West Midlands - of the House Crewe) Bill) (Motion) is agreed to) (High Speed Rail (West Midlands - Crewe) Bill)*** No debate Presentation of Public Petitions Until 7.30pm or Adjournment Debate: Animal for half an hour charities and the covid-19 outbreak (Sir David Amess) Tuesday 19 January 2021 OP No.161: Part 1 3 CONTENTS CONTENTS PART 1: BUSINESS TODAY 4 Chamber 11 Written Statements 13 Committees Meeting Today 22 Committee Reports Published Today 23 Announcements 28 Further Information PART 2: FUTURE BUSINESS 32 A. Calendar of Business Notes: Item marked [R] indicates that a member has declared a relevant interest.