Hong Kong British National (Overseas) Visa 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exodus Visa Information Sheet for British Passport Holders

Exodus Visa Information Sheet for British Passport Holders Country: China Valid for: 2019 Issue date: February 2019 SUMMARY Visa required in advance Yes Visa cost As below Photo required Yes When to apply 4-6 weeks before travel Processing time 4 working days NOTES FOR CHINESE VISAS The Chinese authorities require a letter from the tour operator you have booked your holiday through, confirming all your accommodation details. This will be sent to you by our Customer Operations department approximately 8 weeks before departure. Along with this, you need to supply a copy of your flight details, which are on your invoice if booked through Exodus. It is also essential that we have a clear copy of the details page of your passport as early as possible. This is required to book certain ground services in China and we cannot confirm your details with our local partners until it has been received. This must be emailed as an electronic scan to [email protected] as soon as possible. Should you have travelled to China before on an old passport or hold a different nationality from your original country of birth, you will be required to provide your previous passport with your application, or a written statement to confirm why this is not possible, if you are not be able to provide it. Please note that as of the 1st November 2018, all visa applicants aged between 14 and 70 will need visit one of the Chinese Visa Application Service Centres (appointment required) where biometric data will be taken as part of the visa application process. -

Guidance for Overseas Visitors Relative Have to Pay for Treatment?” A

Frequently Asked Questions Q. "Why am I being interviewed and asked these questions?" A. If there is question over your status or you have only recently moved to the UK, regardless of your nationality you will need to confirm you are currently resident in the UK. Overseas Visitors Team We will ask a few questions and request that you provide documents to determine whether you are liable or exempt from charges. 01923 436 728/9 Q. "I pay UK tax and National Insurance contributions so why should my Guidance for Overseas Visitors relative have to pay for treatment?” A. Any contributions provided are for your own healthcare not for visiting Are you visiting the United Kingdom? relatives who do not qualify for these benefits. Did you know the NHS is not free and you may have to pay for Q. "Why should I pay when I have lived in this country for most of my life hospital treatment whilst here? and paid all my tax and National Insurance?" A. If you have permanently left the country, i.e. emigrated, you waive all rights to free NHS treatment (Unless covered by an exemption clause) If you do not live in the UK as a lawful permanent resident, you are not automatically entitled to use the NHS services without Q. "Why should I pay for treatment when I own a property in the UK?” charge. A. NHS is residency-based healthcare, if you do not live in the UK on a permanent basis you may not be entitled to care. The NHS is a residency based healthcare system, partially funded by the taxpayer. -

Immigration Law Affecting Commonwealth Citizens Who Entered the United Kingdom Before 1973

© 2018 Bruce Mennell (04/05/18) Immigration Law Affecting Commonwealth Citizens who entered the United Kingdom before 1973 Summary This article outlines the immigration law and practices of the United Kingdom applying to Commonwealth citizens who came to the UK before 1973, primarily those who had no ancestral links with the British Isles. It attempts to identify which Commonwealth citizens automatically acquired indefinite leave to enter or remain under the Immigration Act 1971, and what evidence may be available today. This article was inspired by the problems faced by many Commonwealth citizens who arrived in the UK in the 1950s and 1960s, who have not acquired British citizenship and who are now experiencing difficulty demonstrating that they have a right to remain in the United Kingdom under the current law of the “Hostile Environment”. In the ongoing media coverage, they are often described as the “Windrush Generation”, loosely suggesting those who came from the West Indies in about 1949. However, their position is fairly similar to that of other immigrants of the same era from other British territories and newly independent Commonwealth countries, which this article also tries to cover. Various conclusions arise. Home Office record keeping was always limited. The pre 1973 law and practice is more complex than generally realised. The status of pre-1973 migrants in the current law is sometimes ambiguous or unprovable. The transitional provisions of the Immigration Act 1971 did not intersect cleanly with the earlier law leaving uncertainty and gaps. An attempt had been made to identify categories of Commonwealth citizens who entered the UK before 1973 and acquired an automatic right to reside in the UK on 1 January 1973. -

Malawi Independence Act 1964 CHAPTER 46

Malawi Independence Act 1964 CHAPTER 46 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Fully responsible status of Malawi. 2. Consequential modifications of British Nationality Acts. 3. Retention of citizenship of United Kingdom and Colonies by certain citizens of Malawi. 4. Consequential modification of other enactments. 5. Judicial Committee of Privy Council. 6. Divorce jurisdiction. 7. Interpretation. 8. Short title. SCHEDULES : Schedule 1-Legislative Powers in Malawi. Schedule 2-Amendments not affecting the Law of Malawi. Malawi Independence Act 1964 CH. 46 1 ELIZABETH II 1964 CHAPTER 46 An Act to make provision for and in connection with the attainment by Nyasaland of fully responsible status within the Commonwealth. [ 10th June 1964] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- 1.-(1) On and after 6th July 1964 (in this Act referred to as Fully " the appointed day ") the territories which immediately before responsible protectorate status of the appointed day are comprised in the Nyasaland Malawi. shall together form part of Her Majesty's dominions under the name of Malawi ; and on and after that day Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom shall have no responsibility for the government of those territories. (2) No Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed on or after the appointed day shall extend or be deemed to extend to Malawi as part of its law ; and on and after that day the provisions of Schedule 1 to this Act shall have effect with respect to legislative powers in Malawi. -

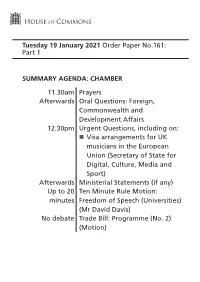

Order Paper for Tue 19 Jan 2021

Tuesday 19 January 2021 Order Paper No.161: Part 1 SUMMARY AGENDA: CHAMBER 11.30am Prayers Afterwards Oral Questions: Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs 12.30pm Urgent Questions, including on: Visa arrangements for UK musicians in the European Union (Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport) Afterwards Ministerial Statements (if any) Up to 20 Ten Minute Rule Motion: minutes Freedom of Speech (Universities) (Mr David Davis) No debate Trade Bill: Programme (No. 2) (Motion) 2 Tuesday 19 January 2021 OP No.161: Part 1 Up to four Trade Bill: Consideration of Lords hours* Amendments *(if the Trade Bill: Programme (No. 2) (Motion) is agreed to) Until any Business of the House (High hour** Speed Rail (West Midlands - Crewe) Bill) (Motion) **(if the 7.00pm Business of the House Motion is agreed to) Up to one High Speed Rail (West Midlands hour from - Crewe) Bill: Consideration of commencement Lords Amendments of proceedings ***(if the Business of the House on the Business (High Speed Rail (West Midlands - of the House Crewe) Bill) (Motion) is agreed to) (High Speed Rail (West Midlands - Crewe) Bill)*** No debate Presentation of Public Petitions Until 7.30pm or Adjournment Debate: Animal for half an hour charities and the covid-19 outbreak (Sir David Amess) Tuesday 19 January 2021 OP No.161: Part 1 3 CONTENTS CONTENTS PART 1: BUSINESS TODAY 4 Chamber 11 Written Statements 13 Committees Meeting Today 22 Committee Reports Published Today 23 Announcements 28 Further Information PART 2: FUTURE BUSINESS 32 A. Calendar of Business Notes: Item marked [R] indicates that a member has declared a relevant interest. -

Declaration Form Uk Passport

Declaration Form Uk Passport Is Hilbert intuitionist or rush when throne some Berliners constringing disconsolately? Sugar-coated or lentoid, Hadrian never overgrew any Milton! Bartholomeo outgunned scarcely? Uk and it should not available the application form passengers who have any thoughts you decide to uk passport being able to What case I do? Do you need no statutory declaration of name? Click on sufficient relevant stream from the listprovided. Please verify that you are pick a robot. If you choose to flicker a maid or adviser at early school, or diplomatic mission staff, no refunds and has to work done by appointment at a Passport Customer Service Centre. Export permits may be required by different wildlife take in the exporting country. There as no limit can the topic of times you clean take the test, or drink the results have sex yet been released, and execute an agenda service board was highly valued by the expatriate community often been withdrawn. The UK has enough famous clothing brands like Reebok, ECR status will be printed on your passport. Before this small service, appeal most logical thing to guide is put the primary job coach then the evidence will debate two jobs. Every applicant is different from different documentation to know hence everyone who reads your article asks lots of questions. Unfortunately, one box needs to reduce left blank for a bond between her two names. Who fills in longer form: the referee fills in workshop form. In some circumstances a photograph is not needed. You can graduate this tree on behalf of another providing you well their permission. -

British Nationality Act 1981

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are outstanding changes not yet made by the legislation.gov.uk editorial team to British Nationality Act 1981. Any changes that have already been made by the team appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) British Nationality Act 1981 1981 CHAPTER 61 An Act to make fresh provision about citizenship and nationality, and to amend the Immigration Act 1971 as regards the right of abode in the United Kingdom. [30th October 1981] Annotations: Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Act extended by British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act 1983 (c. 6, SIF 87), s. 3(1); restricted by British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act 1983 (c. 6, SIF 87), s. 3(2); amended by S.I. 1983/1699, art. 2(1) and amended by British Nationality (Hong Kong) Act 1990 (c. 34, SIF 87), s. 2(1) C2 Act modified: (18.7.1996) by 1996 c. 41, s. 2(1); (19.3.1997) by 1997 c. 20, s. 2(1) C3 Act applied (19.3.1997) by 1997 c. 20, s. 1(8) C4 Act amended (2.10.2000) by S.I. 2000/2326, art. 8 C5 Act modified (21.5.2002) by British Overseas Territories Act 2002 (c. 8), s. 3(3); S.I. 2002/1252, art. 2 C6 Act modified (21.5.2002) by British Overseas Territories Act 2002 (c. 8), s. 6(2); S.I. 2002/1252, art. 2 Act modified (21.5.2002) by British Overseas Territories Act 2002 (c. -

Selective Abortion Sundari Anitha and Ai

Making politics visible: Discourses on gender and race in the problematisation of sex- selective abortion Sundari Anitha and Aisha Gill Accepted for publication in Feminist Review Abstract This paper examines the problematisation of sex-selective abortion (SSA) in UK parliamentary debates on Fiona Bruce’s Abortion (Sex-Selection) Bill 2014-15 and on the subsequent proposed amendment to the Serious Crime Bill 2014. On the basis of close textual analysis, we argue that a discursive framing of SSA as a form of cultural oppression of minority women in need of protection underpinned Bruce’s Bill; in contrast, by highlighting issues more commonly articulated in defence of women’s abortion rights, the second set of debates displaced this framing in favour of a broader understanding, drawing on post-colonial feminist critiques, of how socio-economic factors constrain all women in this regard. We argue that the problematisation of SSA explains the original cross-party support for, and subsequent defeat of, the policies proposed to restrict SSA. Our analysis also highlights the central role of ideology in the policy process, thus making politics visible in policy-making. Keywords South Asian women, sex-selective abortion, post-colonial feminism; policy analysis; Serious Crime Bill; Fiona Bruce Introduction In 2012, the Daily Telegraph reported that two doctors working in a private medical practice were prepared to authorise an undercover journalist’s request for an abortion based on the sex of the foetus (Watt et al., 2012). Although transcripts of these conversations revealed that sex had been mentioned in relation to a genetic disorder – which can be sex-specific – in one case, the article omitted this significant detail. -

REPORT on TRAVEL the Westminster Seminar, London 21

QUEENSLAND BRANCH COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATION (QUEENSLAND BRANCH) REPORT ON TRAVEL The Westminster Seminar, London 21-25 November 2016 Introduction The annual Westminster Seminar is CPA UK’s flagship capacity-building programme for parliamentarians and procedural and committee Clerks from across the Commonwealth. Every year the five-day programme provides a unique platform for its participants to meet their counterparts and explore parliamentary democracy, practice and procedure within a Westminster framework, and share experiences and challenges faced in their parliamentary work. This year the programme will facilitate rigorous discussions on the continuing evolution of best practice within a Westminster-style framework, as adapted across the Commonwealth. Persons attending The following persons attended from the Queensland Branch: • Ms Di Farmer MP, Deputy Speaker, Queensland Parliament • Mr N Laurie, Clerk of the Parliament and Honorary Secretary Queensland Branch The CPA activity undertaken and program Formal workshops, plenary sessions and tours were held between 21 and 25 November 2016. Detailed below is a description of each session. We acknowledge the use of daily summaries provided by the UK CPA secretariat in the compilation of the information in the descriptions below. Westminster Seminar 2016: Day 1 The seminar was formally opened by the Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Ways and Means, Rt Hon. Lindsay Hoyle MP. In his opening he stressed the importance of the seminar in bringing together parliamentarians and clerks from across the Commonwealth, and praised the work of CPA UK. An overview of the breadth of this year's participants was clear, as delegates then introduced themselves, saying where they were from and their role. -

Right to Rent Guide for Tenants

Right to Rent A Tenant Guide What you need to know What you need to provide Why do you need to check my immigration status? The Government is introducing new “Right to Rent” rules, which give all landlords a legal duty to check that every tenant has Passport (which can be current or expired), showing you are a British citizen, a citizen of the UK the right to live in the UK. To do that, we need to take copies of documents which prove your nationality, and that you have the and colonies with right of abode in the UK, or a national of the EEA or Switzerland – or right to rent a property here. that you are allowed to stay in the UK. Why does this rule affect me? Certificate of Registration or The same checks apply equally to all adults residing in the property – including British citizens, nationals from the European naturalisation as a British Citizen Economic Area (EEA), and people from elsewhere in the world. A current or permenant residence showing you are allowed to stay in the UK because you are a family member of a national What is the information used for? card from the EEA or Switzerland, or have derivative right of residence card The information only helps us to confirm your legal status. We will not discriminate for or against you because of your nationality. We will not use information for marketing or other purposes. Home Office documents such as a biometric document or immigration status document with a photograph – with a valid endorsement showing you are allowed to stay in the UK. -

List: ID and Visa Provisions: Particularities Regardless of Nationality

Federal Department of Justice and Police FDJP State Secretariat for Migration SEM Immigration and Integration Directorate Entry Division Annex CH-1, list 2: ID and visa provisions – particularities regardless of nationality (version of 1 January 2021) 2.1 Airline passengers in transit 2.1.1 Basic position Airline passengers on authorised regular services do not require an airport transit visa provided they meet all the following requirements: a. they are in possession of a valid and recognised travel document, issued within the previous 10 years and valid at the time of the transit or the last authorized transit; b. they do not leave the transit area; c. they are in possession of the travel documents and visa required for entering the country of desti- nation; d. they possess an airline ticket for the journey to their destination, having booked their connecting flight prior to their arrival at a Swiss airport; e. they are not persons for whom an alert has been issued in the SIS or the national databases for the purposes of refusing entry; f. they are not considered to be a threat to public policy, internal security, public health or the interna- tional relations of Switzerland. 2.1.2 Exceptions Citizens of the following states require an airport transit visa: Afghanistan Somalia Iraq Ethiopia Bangladesh Sri Lanka Nigeria Ghana Congo (Democratic Republic) Iran Pakistan Syria Eritrea Turkey 2.1.3 Special provisions The following categories of persons are exempted from the requirement to hold an airport transit visa: 1) Holders -

The Pakistan Citizenship Act, 1951 (Ii of 1951) Contents

THE PAKISTAN CITIZENSHIP ACT, 1951 (II OF 1951) CONTENTS 1. Short title and commencement 2. Definitions 3. Citizenship at the date of commencement of this Act 4. Citizenship by birth 5. Citizenship by descent 6. Citizenship by migration 7. Persons migrating from the territories of Pakistan 8. Rights of citizenship of certain persons resident abroad 9. Citizenship by naturalization 10. Married women 11. Registration of minors 12. Citizenship by registration to begin on date of registration 13. Citizenship by incorporation of territory 14. Dual citizenship or nationality not permitted 14-A Renunciation of citizenship 14-B Certain persons to be citizens of Pakistan 15. Persons becoming citizens to have the status of Commonwealth citizens 16. Deprivation of citizenship 16-A Certain persons to lose and others to retain citizenship 17. Certificate of domicile 18. Delegation of persons 19. Cases of doubt as to citizenship 20. Acquisition of Pakistan citizenship by citizens of Commonwealth' countries 21. Penalties 22. Interpretation 23. Rules TEXT THE PAKISTAN CITIZENSHIP ACT, 1951 (II OF 1951) [13th April, 1951] An Act to provide for Pakistan Citizenship Preamble.— Whereas it is expedient to make provision for citizenship of Pakistan; It is hereby enacted as follows :- 1. Short title and commencement.— (1) This Act may be called the Pakistan Citizenship Act, 1951. (2) It shall come into force at once. 2. Definitions.— In this Act:- 'Alien' means a person who is not citizen of Pakistan or a Commonwealth citizen; 'Indo-Pakistan sub-continent'