Defying Apartheid: an Interview with Johan Van Der Vyver by Matthew Cavedon*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRENEGOTIATION Ln SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) a PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS

PRENEGOTIATION lN SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) A PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS BOTHA W. KRUGER Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: ProfPierre du Toit March 1998 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Die opvatting bestaan dat die Suid-Afrikaanse oorgangsonderhandelinge geinisieer is deur gebeurtenisse tydens 1990. Hierdie stuC.:ie betwis so 'n opvatting en argumenteer dat 'n noodsaaklike tydperk van informele onderhandeling voor formele kontak bestaan het. Gedurende die voorafgaande tydperk, wat bekend staan as vooronderhandeling, het lede van die Nasionale Party regering en die African National Congress (ANC) gepoog om kommunikasiekanale daar te stel en sodoende die moontlikheid van 'n onderhandelde skikking te ondersoek. Deur van 'n fase-benadering tot onderhandeling gebruik te maak, analiseer hierdie studie die oorgangstydperk met die doel om die struktuur en funksies van Suid-Afrikaanse vooronderhandelinge te bepaal. Die volgende drie onderhandelingsfases word onderskei: onderhande/ing oor onderhandeling, voorlopige onderhande/ing, en substantiewe onderhandeling. Beide fases een en twee word beskou as deel van vooronderhandeling. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

The Geology of the Country Around Potchefstroom and Klerksdorp

r I! I I . i UNION OF SOUTH AFRICA DJ;;~!~RTMENT OF MINES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THE GEOLOGY OF THE COUNTRY AROUND POTCHEFSTROOM AND KLERKSDORP , An Explanation of Sheet No. 61 (Potchefstroom). BY LOUIS T. NEL, D.Se., F.G.S., F. C. TRUTER, M.A., Ph.D, J. WILLEMSE, Ph.D., incorporating previous observations by E. T. MELLOR, D.Se., F,G.S. Published by Authority of the Honourable the Minister of Mines {COPYRiGHT1 PRINTED IN THE UNION OF SoUTH AFRICA BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER. PRETORIA 1939 G.P.-S.4423-1939-1,500. 9 ,ad ;est We are indebted to Western Reefs Exploration and Development Company, Limited, and to the Union Corporation, Limited, who have generously furnished geological information obtained in the red course of their drilling in the country about Klerksdorp. We are also :>7 1 indebted to Dr. p, F. W, Beetz whose presentation of the results of . of drilling carried out by the same company provides valuable additions 'aal to the knowledge of the geology of the district, and to iVIr. A, Frost the for his ready assistance in furnishing us with the results oUhe surveys the and drilling carried out by his company, Through the kind offices ical of Dr. A, L du Toit we were supplied with the production of diamonds 'ing in the area under description which is incorporated in chapter XL lim Other sources of information or assistance given are specifically ers acknowledged at appropriate places in this report. (LT,N.) the gist It-THE AREA AND ITS PHYSICAL FEATURES, ond The area described here is one of 2,128 square miles and extends )rs, from latitude 26° 30' to 27° south and from longtitude 26° 30' to the 27° 30' east. -

COVID-19 Laboratory Testing Sites

Care | Dignity | Participation | Truth | Compassion COVID-19 Laboratory testing sites Risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing for COVID-19 The information below should give invididuals a clear understanding of the process for risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing of patients, visitors, staff, doctors and other healthcare providers at Netcare facilities: • Risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing of ill individuals Persons who are ill are allowed access to the Netcare facility via the emergency department for risk assessment and screening. Thereafter the person will be clinically assessed by a doctor and laboratory testing for COVID-19 will subsequently be done if indicated. • Laboratory testing of persons sent by external doctors for COVID-19 laboratory testing at a Netcare Group facility Individuals who have been sent to a Netcare Group facility for COVID-19 laboratory testing by a doctor who is not practising at the Netcare Group facility will not be allowed access to the laboratories inside the Netcare facility, unless the person requires medical assistance. This brochure which contains a list of Ampath, Lancet and Pathcare laboratories will be made available to individuals not needing medical assistance, to guide them as to where they can have the testing done. In the case of the person needing medical assistance, they will be directed to the emergency department. No person with COVID-19 risk will be allowed into a Netcare facility for laboratory testing without having consulted a doctor first. • Risk assessment and screening of all persons wanting to enter a Netcare Group facility Visitors, staff, external service providers, doctors and other healthcare providers are being risk assessed at established points outside of Netcare Group hospitals, primary care centres and mental health facilities, prior to them entering the facility. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

![NORTH WEST I NOORDWES ~ ~ ~ PROVINCIAL GAZETTE ~ I PROVINCIAL GAZETTE I ~ ~ ~@].@]~ ~ ~ ~ JUNE ~ ~ Vol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2135/north-west-i-noordwes-provincial-gazette-i-provincial-gazette-i-june-vol-942135.webp)

NORTH WEST I NOORDWES ~ ~ ~ PROVINCIAL GAZETTE ~ I PROVINCIAL GAZETTE I ~ ~ ~@].@]~ ~ ~ ~ JUNE ~ ~ Vol

l!: @] ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ NORTH WEST i NOORDWES ~ ~ ~ PROVINCIAL GAZETTE ~ I PROVINCIAL GAZETTE i ~ ~ ~@].@]~ ~ ~ ~ JUNE ~ ~ Vol. 252 30 JUNIE 2009 No. 6653 ~ I I @] @] 2 No. 6653 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, 30 JUNE 2009 CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICES ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 197 Town-planning and Townships 197 Ordonnansie op Dorpsbeplanning en Ordinance (15/1986): Amendment Dorpe (15/1986): Wysigingskema 25...... 8 6653 Scheme 25 . 8 6653 198 do.: Rustenburg-wysigingskema 547...... 9 6653 198 do.: Rustenburg Amendment Scheme 199 do.: Ditsobotla-wysigingskema 43 .......... 9 6653 547 .. 8 6653 200 Wet op Opheffing van Beperkings 199 do.: Ditsobotla Amendment Scheme 43 . 9 6653 (84/1967): Opheffing van voorwaardes: 200 Removal of Restrictions Act (84/1967): Erf 2449, Flamwood 10 6653 Removal of conditions: Erf 2449, Flamwood . 10 6653 PLAASLIKE BESTUURSKENNISGEWINGS 208 Town-planning and Townships LOCAL AUTHORITY NOTICES Ordinance (15/1986): Local Municipality 208 Town-planning and Townships of Madibeng: Brits Amendment Scheme Ordinance (15/1986): Local Municipality 1/465....................................................... 10 6653 of Madibeng: Brits Amendment Scheme 209 Ordonnansie op Dorpsbeplanning en 1/465 . 10 6653 Dorpe (15/1986): Madibeng Muni 209 do.: do.: Rezoning: Erf 1874, Brits X9 .. 11 6653 sipaliteit: Hersonering: Erf 1874, 210 Rustenburg Amendment Scheme 478: Brits X9.................................................... 11 6653 Cancellation of notice .. 11 6653 210 Rustenburg-wysigingskema 478: Kansel- 211 Rustenburg Amendment Scheme 421: lasie van kennisgewing............................. 12 6653 Cancellation of notice . 12 6653 211 Rustenburg-wysigingskema 421: Kansel- 212 Local Government Ordinance (17/1939): lasie van kennisgewing 12 6653 Maquassi Hills Local Municipality: 212 Ordonnansie op Plaaslike Bestuur Closing: Portion of street adjacent to Erf (17/1939): Maquassi Hills Plaaslike 599 and Erf 600, Wolmaransstad Munisipaliteit: Sluiting: Gedeelte van Extension 5 . -

A Study Into the Meanings of Sports As a Medium of HIV Awareness in a South African Township

Active HIV Awareness A study into the meanings of sports as a medium of HIV awareness in a South African township Utrecht University Utrecht School of Governance Organization, Culture & Management Author: Maikel Waardenburg Utrecht, February 2006 Active HIV Awareness A study into the meanings of sports as a medium of HIV awareness in a South African township Utrecht University Utrecht School of Governance Organization, Culture & Management Supervisor: drs. Marinette Oomen Author: Maikel Waardenburg Himalaya 164 3524 XJ Utrecht, the Netherlands [email protected] Student number: 0144274 Utrecht, February 2006 The picture on the cover of this document is property of Martijn Bergmans Extensive paper written for the final year of the study ‘Public Administration & Organizational Science’ at Utrecht University Active HIV Awareness Contents Summary iv List of Tables and Figures vi List of Abbreviations vii Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Research Design 3 1.1 Central Research Question 3 1.2 Research Paradigm 4 1.3 Research Object 5 1.4 Research Methods 5 1.4.1 Observations 5 1.4.2 Interviews 6 1.4.3 Participation 7 1.5 Public and Scientific Relevance 8 Chapter 2 The Big Picture 10 2.1 Early South Africa 10 2.2 Political Struggle in South Africa 11 2.3 Present-day South Africa 13 2.3.1 Present-day Government & Politics 14 2.3.2 Economy of South Africa 16 2.3.3 Socio-cultural features of South Africa 17 2.4 The HIV/AIDS Pandemic in South Africa 17 2.4.1 HIV Determinants in South Africa 19 2.4.2 Government’s Response -

Wetland Plant Communities in the Potchefstroom Municipal Area, North-West, South Africa

Bothalia 28,2: 213-229 (1998) Wetland plant communities in the Potchefstroom Municipal Area, North-West, South Africa S.S. CILLIERS*, L.L. SCHOEMAN* and G.J. BREDENKAMP** Keywords: Braun-Blanquet, DECORANA. disturbed areas, MEGATAB, TURBOVEG. TWINSPAN, urban open spaces ABSTRACT Wetlands in natural areas in South Africa have been described before, but no literature exists concerning the phyto sociology of urban wetlands. The objective of this study was to conduct a complete vegetation analysis of the wetlands in the Potchefstroom Municipal Area. Using a numerical classification technique (TWINSPAN) as a first approximation, the classification was refined by using Braun-Blanquet procedures. The result is a phytosociological table from which a number of unique plant communities are recognised. These urban wetlands are characterised by a high species diversity, which is unusual for wetlands. Reasons for the high species diversity could be the different types of disturbances occurring in this area. Results of this study can be used to construct more sensible management practises for these wetlands. CONTENTS Many natural wetlands have been destroyed in the course of agricultural, industrial and urban development Introduction..............................................................213 (Archibald & Batchelor 1992), and are regarded as one Study area................................................................ 215 of South Africa’s most endangered ecosystem types Materials and methods..............................................215 (Walmsley -

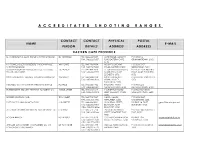

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Biko Met I Must Say, He Nontsikelelo (Ntsiki) Mashalaba

LOVE AND MARRIAGE In Durban in early 1970, Biko met I must say, he Nontsikelelo (Ntsiki) Mashalaba Steve Biko Foundation was very politically who came from Umthatha in the Transkei. She was pursuing involved then as her nursing training at King Edward Hospital while Biko was president of SASO. a medical student at the I remember we University of Natal. used to make appointments and if he does come he says, “Take me to the station – I’ve Daily Dispatch got a meeting in Johannesburg tomorrow”. So I happened to know him that way, and somehow I fell for him. Ntsiki Biko Daily Dispatch During his years at Ntsiki and Steve university in Natal, Steve had two sons together, became very close to his eldest Nkosinathi (left) and sister, Bukelwa, who was a student Samora (right) pictured nurse at King Edward Hospital. here with Bandi. Though Bukelwa was homesick In all Biko had four and wanted to return to the Eastern children — Nkosinathi, Cape, she expresses concern Samora, Hlumelo about leaving Steve in Natal and Motlatsi. in this letter to her mother in1967: He used to say to his friends, “Meet my lady ... she is the actual embodiment of blackness - black is beautiful”. Ntsiki Biko Daily Dispatch AN ATTITUDE OF MIND, A WAY OF LIFE SASO spread like wildfire through the black campuses. It was not long before the organisation became the most formidable political force on black campuses across the country and beyond. SASO encouraged black students to see themselves as black before they saw themselves as students. SASO saw itself Harry Nengwekhulu was the SRC president at as part of the black the University of the North liberation movement (Turfloop) during the late before it saw itself as a Bailey’s African History Archive 1960s. -

South African Jewish Board of Deputies Report of The

The South African Jewish Board of Deputies JL 1r REPORT of the Executive Council for the period July 1st, 1933, to April 30th, 1935. To be submitted to the Eleventh Congress at Johannesburg, May 19th and 20th, 1935. <י .H.W.V. 8. Co י É> S . 0 5 Americanist Commiitae LIBRARY 1 South African Jewish Board of Deputies. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL. President : Hirsch Hillman, Johannesburg. Vice-President» : S. Raphaely, Johannesburg. Morris Alexander, K.C., M.P., Cape Town. H. Moss-Morris, Durban. J. Philips, Bloemfontein. Hon. Treasurer: Dr. Max Greenberg. Members of Executive Council: B. Alexander. J. Alexander. J. H. Barnett. Harry Carter, M.P.C. Prof. Dr. S. Herbert Frankel. G. A. Friendly. Dr. H. Gluckman. J. Jackson. H. Katzenellenbogen. The Chief Rabbi, Prof. Dr. j. L. Landau, M.A., Ph.D. ^ C. Lyons. ^ H. H. Morris Esq., K.C. ^י. .B. L. Pencharz A. Schauder. ^ Dr. E. B. Woolff, M.P.C. V 2 CONSTITUENT BODIES. The Board's Constituent Bodies are as. follows :— JOHANNESBURG (Transvaal). 1. Anykster Sick Benefit and Benevolent Society. 2. Agoodas Achim Society. 3. Beth Hamedrash Hagodel. 4. Berea Hebrew Congregation. 5. Bertrams Hebrew Congregation. 6. Braamfontein Hebrew Congregation. 7. Chassidim Congregation. 8. Club of Polish Jews. 9. Doornfontein Hebrew:: Congregation.^;7 10. Eastern Hebrew Benevolent Society. 11. Fordsburg Hebrew Congregation. 12. Grodno Sifck Benefit and Benevolent Society. 13. Habonim. 14. Hatechiya Organisation. 15. H.O.D. Dr. Herzl Lodge. 16. H.O.D. Sir Moses Montefiore Lodge. 17. Jeppes Hebrew Congregation, 18. Johannesburg Jewish Guild. 19. Johannesburg Jewish Helping Hand and Burial Society.